Phillis Wheatley and the Birth of African American Consciousness. Part I.

Greetings, Steemians. I want to share with you a series of posts on another academic interest of mine: African-American Literature. I believe it is more than pertinent to discuss some of the intellectual background of the African American struggles for equality and respect, especially now, in the context of embarrassing and painful recent events. I would like to start with Phillis Wheatley. I have divided an analysis of some of her poems into 3 posts to lighten its reading.

Your comments, as always, are more than welcome!

Source

Source

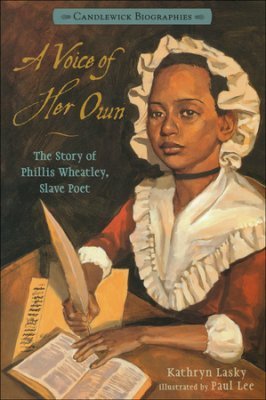

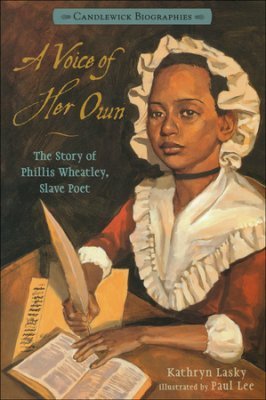

Named after the slave ship that brought her to America from West Africa, Phillis Wheatley would become the first African American woman to be published (Poems on Various Subjects, Religious and Moral, London, 1773). Purchased by John Wheatley, a wealthy merchant and tailor, as a servant for his wife Susanna, Phillis was a privileged house slave and benefitted from the Wheatley children’s education. She read what they read, she learned what they learned, and then some more. She mastered the classics and started writing her own poetry probably at 12. She was praised and admired in England and in the American colonies. She wrote poems to George Washington and interchanged some letters with him. However, she was also criticized by many, and despite the attestation letter that accompanied her book of poems, in which a selected group of white intellectuals and officials (among them John Erving, Reverend Charles Chauncey, John Hancock, Thomas Hutchinson and Samuel Mather) certified the authenticity of the poems written by her, people like Thomas Jefferson belittled her achievement.

Source

Source

Judging by the amount of scholarship produced in the last decades on Phillis Wheatley (1754?-1784), most of which is turning now towards a growing interest in rediscovering her originality as an artist, I think that history is finally paying its due to this illustrious African American. It is precisely her often misunderstood and reductively interpreted religiosity that I wish to address here. Albertha Sistrunk (1980), for instance, affirms that Wheatley, having a pious character “bore only feelings of love devotion, and gratitude for her slave family: she obviously harbored no feelings of revenge and hatred against anyone for her ‘lowly’ state in life” (in Levernier n3 34). Contrary to this belief, I want to argue that Phillis Wheatley consistently entertained the idea of revenge and the bloody redemption of her oppressed race; furthermore, it was precisely in her “religious poems” (specifically in her biblical paraphrases “Goliath of Gath” and “Isaiah”) where Wheatley pushed her imagination to the verge of psychopathic retribution.

Source

Source

It is hard to understand how decades of scholarship went so wrong about interpreting and understanding Phillis Wheatley’s multi-layered poesy (I may get to understand Thomas Jefferson’s abhorrence and that of those of his generation). If there was some sense of piety in Wheatley’s poetic art, it was in the Roman sense, as John Shields discusses Pietas in the American Aeneas: “devotion to the gods, one’s family and one’s country” (xxxii). Wheatley’s idea of family, as I will discuss later, was blurry and traumatic, her sense of belonging to the country that adopted her was never certain, and in terms of religion, in Wheatley’s case we have to talk about several Gods (the African, the Christian, and the Classical).

Source

Source

Although Wheatley was intermittently praised and attacked from the very moment she published her Poems on Various Subjects, Religious and Moral (1773), the 1970s and 80s seem to combine the most outrageous readings of the poet who, in my opinion, should be called the black muse (contrary to what many critics say, she became—even if vicariously—the muse for the African American artists who followed). Fortunately, left behind are the works of Eleanor Smith (1974), Angelene Jamison (1974), Terrence Collins (1975), J. Saunders Redding (1982), Blyden Jackson (1989), whose History of Afro-American Literature should be revised, and many other scholars whose myopic reading of Wheatley’s work made them see it as imitative, white-oriented, detached from race conscience, and ultimately the result of a tamed, religiously indoctrinated mind.

The Genre

Contrary to what most critics argue regarding the “pervasive influence of religion on Wheatley’s poetry,” as Levernier remarks (21-22), I suggest a reading of Wheatley’s appropriation of the biblical texts more in the vein of Ann Douglas’ definition of appropriation: "to appropriate something is to abstract it by taking it out of its matrix, its indigenous original context, in order to resituate it in a plan of one's own making, a place alien to its natural habitat and design"(in Rubenstein); as well as Leland Ryken’s approach to Milton’s biblical allusions and paraphrases. In fact, Ryken, quoting C. S. Lewis, suggests the distinction between the bible as a “source” and the bible as “influence:” “A source gives us things to write about; an influence prompts us to write in a certain way.” I find this distinction extremely useful to understand Wheatley’s poetry (actually I find it “interesting” that scholars can make this distinction in Milton’s work, but not in Wheatley’s). However, in Milton’s case, according to Ryken, we can observe the bible’s “descriptive technique” (5), “a reliance on simple, concrete, elemental images” (4); in Wheatley’s poetry, on the other hand, the rendering is more toward the visual, almost pictorial representation of her “intertextual epic” (Shields American Aeneas 225).

Source

Source

Thus, the bible provided Wheatley with rhetorical and theological tools that, in combination with her classical instruction and her rather eclectic religious views, built up her artistic, spiritual, and intellectual vision of the world and the natural laws that must rule the interaction among the people in it. The religious mode in Wheatley became also a form of artistic, political, and psychological escapade. Her numerous elegies, for instance (allegedly innocuous poems) served as vehicles for Wheatley’s personal and political expression. “On the Death of General Wooster,” for instance she castigates Americans hypocritical struggle for freedom while holding “in bondage Afric’s blameless race” (149). Also, in several instances (“On the Death of a Young Gentleman” (27) and in “To the Right Honorable William, Earl of Dartmouth” (73), for example), Wheatley breaks with the monolithic god by particularizing the god the white man will meet after death. She talks about “his god” and “thy god” respectively, and we should assume that that deity was not necessarily her god. Through her elegies, I would like to believe, Wheatley provides the white people with the illusion of the “compensation for the evils past” (19), an illusion she tears apart in the two main biblical paraphrases I will later analyze.

Source

Source

In any case, the scriptural tradition, or the art of paraphrasing the bible, was not a new thing in Wheatley’s time; it was not something Wheatley did as a result of her indoctrination and artistic limitations. In fact, as Shields points out in “Phillis Wheatley’s Use of Classicisms,” “In combining Christian and classical elements, Wheatley falls within a common tradition which began before the Renaissance and extends through Elliot” (102). Thus, following Ryken’s argument, I propose that “instead of viewing the Bible as primarily doctrinal,” we should—when reading Wheatley’s appropriation of it—“look upon it as a work of imagination” (3). That is, the bible becomes one more literary text, a text Wheatley so masterfully adapted to her agenda and which provided her with a channel to drain her thirst of revenge (at a personal level) and an almost prophetic voice in analyzing the unavoidable tragic resolution to the colonies social contradictions (at the public level).

To be able to read Phillis’ anger we have to be able to read her moving confessions of anxiety and suffering derived from the separation from her parents and motherland. Roberta Rubenstein, in her study of Toni Morison’s obsession throughout her work with issues of “dismembering” and “re-membering,” quotes psychoanalyst John Bowlby’s theory on “the loss of a parent during early childhood” which according to Bowlby, “‘gives rise not only to separation anxiety and grief but to processes of mourning in which aggression, the function of which is to achieve reunion, plays a major part’" (149-150). Wheatley expresses these aggressive feelings in several ways in poems such as “On Recollection,” where images of the middle passage can be identified, “On Imagination,” and more eloquently in “To the Right Honorable William, Earl of Dartmouth."

Should you, my lord, while you peruse my song,

Wonder from whence my love for Freedom sprung,

Whence flow these wishes for the common good,

By feeling hearts alone best understood,

I, young in life, by seeming cruel fate

Was snatch'd from Afric's fancy'd happy seat:

What pangs excruciating must molest,

What sorrows labour in my parent's breast?

Steel'd was that soul and by no misery mov'd

That from a father seiz'd his babe belov'd:

Such, such my case. And can I then but pray

Others may never feel tyrannic sway? (73-74:20-31 my emphasis).

Thanks for the visit. I will be posting the remaining parts of this analysis shortly.

Works Cited or Consulted

Collins, Terrence. “Phillis Wheatley: The Dark Side of Her Poetry.” Phylon 36 (1975): 78-88.

Jackson, Blyden. A History of Afro-American Literature. V I. The Long Beginning, 1746-1895. Louisiana State U.P.: Baton

Rouge, 1989.

Jamison, Angelene. “Analysis of Selected Poetry of Phillis Wheatley.” Journal of Negro Education 43 (1974): 408-16.

Levernier, James A. “Plillis Wheatley and the New England Clergy.” EAL 26.1 (1991): 21-39.

Lewis, R. W. B. The American Adam: Innocence, Tragedy and Tradition in the Nineteenth Century. U of Chicago P:

Chicago, 1968.

O’Neale, Sondra. “A Slave Subtle War: Phillis Wheatley’s Use of Biblical Myth and Symbol.” EAL 21.2 (1986): 144-65.

Redding, J. Saunders. “Phillis Wheatley.” The Dictionary of American Negro Biography. Ed. Rayford W. Logan and

Michael R. Winston. New York: Norton, 1982.

Rubenstein, Roberta. “Singing the Blues / Reclaiming jazz: Toni Morrison and Cultural Mourning.” Journal for the

Interdisciplinary Study of Literature 31.2 (1998): 147-163.

Scheick, William J. “Subjection and Prophesy” College Literature 22.3 (1995): 122-29.

Shields, John C. The American Aeneas. University of Tennessee Press: Knoxville, 2001

---. “Phillis Wheatley's Use of Classicism.” American Literature 52 (1980): 97-111.

---. “Phillis Wheatley and Mather Byles: A Study in Literary Relationship.” CLA 23.4 (1980): 377-90.

Sims, James H. and Leland Ryken. Milton and Scriptural Tradition. The Bible into Poetry. U of Missouri P: Columbia, 1984.

Smith, Eleanor. “Phillis Wheatley: A Black Perspective.” Journal of Negro Education 43 (1974): 401-07.

Wheatley, Phillis. The Collected Works. Ed. John Shields. Oxford UP: Oxford, 1988.

Source

Source Source

Source Source

Source Source

Source Source

Source Source

Source

Mi amigo, me debes la traducción. Pensé que aquí la encontraría. Un abrazo.

Downvoting a post can decrease pending rewards and make it less visible. Common reasons:

Submit

Gracias por el apoyo. Mas tarde publico la version en espanol.

Downvoting a post can decrease pending rewards and make it less visible. Common reasons:

Submit

I love you've made such a well written post on the "black muse," @hlezama. You've made a great work on its translation, too.

No need to be a believer to love this piece:

She's terrific.

Downvoting a post can decrease pending rewards and make it less visible. Common reasons:

Submit

Thanks for your encomium :)

It is an honor to have you, now a consummate poetess, as a reader.

It is great that you bring that poem to the comment, her famous "On being brought to America". It is a good example of her cleverness in the use of language and religious references. It clearly questions white moral and religious supremacy and even Christianity itself, and she got away with it!

Downvoting a post can decrease pending rewards and make it less visible. Common reasons:

Submit

She did ♥

Thank YOU!

Downvoting a post can decrease pending rewards and make it less visible. Common reasons:

Submit

Greetings, @hlezama,

I discovered this gem of yours, courtesy of browsing @marlyncabrera's Steemit blog...

I found reading your observations about Phillis Wheatley quite fascinating, and if you would kindly respond to this message, I'll be able to express my gratitude a little bit.

😄😇😄

Downvoting a post can decrease pending rewards and make it less visible. Common reasons:

Submit

How not to? Thanks for the gesture, @creatr. It's a big compliment for me that you took the time to read and comment an old post of mine.

Downvoting a post can decrease pending rewards and make it less visible. Common reasons:

Submit

Oh, it is absolutely great you have found @hlezama, @creatr ☻

Hey, @hlezama, you can click on the GIF, and it'll take you to @creatr's library. This is good basically because of two things, he's got excellent and interesting material to share, and it makes you want to organize your posts, too ☻

Downvoting a post can decrease pending rewards and make it less visible. Common reasons:

Submit

Thank you, I am glad.

Actually, I have been aware of @hlezama before, because he has graced my blog with his very kind comments and support in the past. However, before now I have sadly not taken enough time to explore his excellent writings. Thanks for helping to remedy that! ;)

Downvoting a post can decrease pending rewards and make it less visible. Common reasons:

Submit