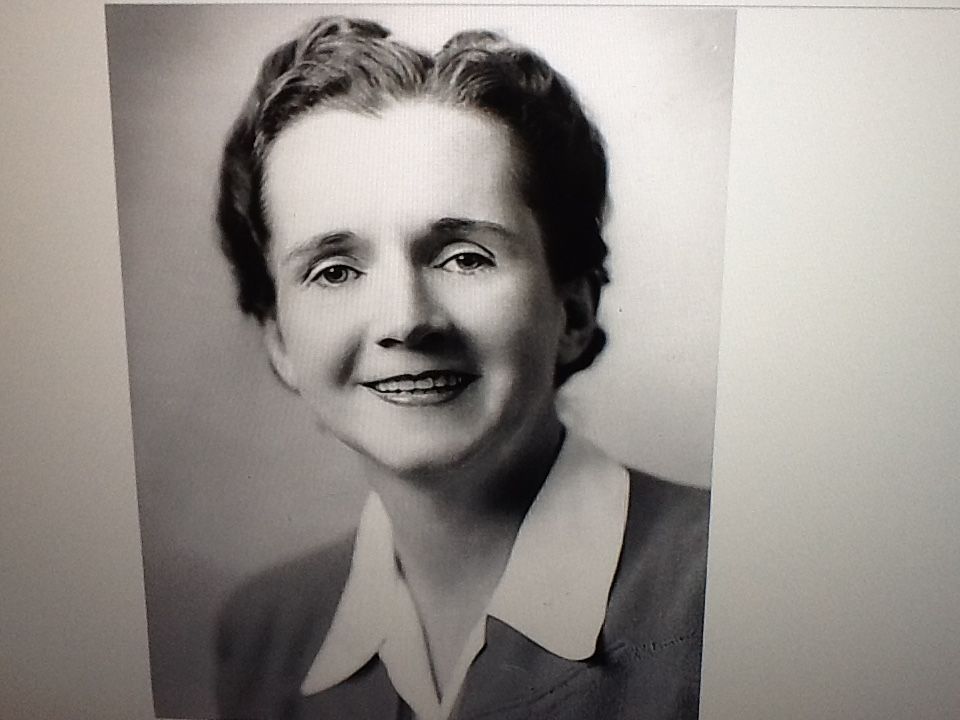

RACHEL CARSON AND THE SILENT SPRING

INTRODUCTION

The environment and ecological concerns are often a feature of news reports and documentaries these days. Reports of extreme weather events usually include a discussion over whether it's due to man-made global warming. The BBC's flagship nature documentary, Blue Planet II, includes warnings that our oceans are becoming dangerously polluted. It's difficult to avoid the message that environmental issues concerns us all.

But it was not always thus. Just a few generations ago, not one person in a hundred had heard the word 'ecology'. In this essay, I want to talk about someone who did significant work in bringing environmentalism to a far wider audience. That someone was Rachel Carson.

EARLY YEARS

(Image from wikimedia commons)

She was born on May 27 1907, the daughter of Robert Warden Carson and Maria Frazier Carson (nee McLean). Rachel grew up on the family's 65 acre farm, and from an early age she loved to read and write. She was just ten years old when she had her first story published (in St. Nicholas Magazine). Inspired by the farmland which she often explored, the natural world featured in both her writings and the stories she most enjoyed reading (such as the works of Beatrix Potter and, later, the works of Herman Melville and Joseph Conrad).

Having graduated top of the class of forty five students from high school in Parnassus, Pennsylvania, Rachel enrolled at what is now known as Chatham University, but which was then called the Pennsylvania College for Women. Originally, she studied English but in January 1928 she switched her major to biology. That same year, she was admitted to graduate standing at Johns Hopkins University, but financial difficulties meant she remained at Pennsylvania College for her senior year. She did, however, continue her studies in Zoology and Genetics at Johns Hopkins in the autumn of 1929. By 1932 she had earned her master's degree in zoology, but in 1934 she was obliged to give up her ambition of going for a doctorate in order to teach full-time so she could support the family.

A year later, in 1935, Robert Warden Carson died, leaving Rachel to care for her elderly mother. She was urged by her undergraduate biology mentor, Mary Scott Skinner, to take up a temporary position with the US bureau of Fisheries, where she was tasked with writing radio copy for a series called 'Romance Under the Waters'. Around the same time, she submitted articles to local newspapers and magazines, all based on her research into marine life for the aforementioned series. By 1962, Rachel really had become a successful writer. Her book, 'The Sea Around Us', spent thirty nine weeks at the top of the New York bestseller list and was translated into thirty languages.

SILENT SPRING

It was also in 1962 (June 16 1962 to be precise) that New Yorker magazine published the first three instalments of what is probably her most famous work: 'Silent Spring'. It was quite a departure from her earlier publications, which, as we have seen, were all concerned with marine biology. 'Silent Spring' was instead concerned with chlorinated pesticides, particularly DDT, which at the time could be purchased in bulk for fifty cents a pound. DDT had proven to be very effective at killing insects and had been hailed as something of a saviour during World War II, the first war to see fewer deaths from disease than from combat wounds. DDT sprays and dusting a were almost entirely responsible for this, as the practice killed off typhus-carrying fleas.

(Image from wikimedia commons)

By the time Rachel began writing Silent Spring, the USDA had begun aerial spraying of DDT over Long Island and New England, in an effort to eradicate pests such as gypsy moths, caterpillars and mosquitos. But not everyone considered this to be a good thing. People began to write angry letters to the New Yorker, detailing how this chemical assault was not only killing pests but also birds, bees, and other beneficial lifeforms. Furthermore, as part of a family of chemicals called Chlorinated hydrocarbons, DDT is not water soluble but is soluble in fat. This property meant the chemical became stored in the fatty tissues of any animal, therefore building up in the food chain. By 1950, people living in the US had an average toxicity of 5.3 parts per million. By the time 'Silent Spring' was published, DDT production had hit its peak of 180 million pounds per year, and the amount measured in human tissue also peaked, at 12.6 parts per million.

Rachel was not opposed to the moderate use of safe pesticides and biological control agents. But, just like the people writing angry letters about the death of birds and bees, she considered this abundance of spraying to be potentially harmful. "Can anyone believe it is possible to lay down such a barrage of poison on the surface of the Earth without making is unfit for all life?", she wrote.

The book rejected the norm for scientific papers at the time, which was to be written in a rigorous, objective and unemotional style. Instead, Rachel used a mixture of fables and science to paint a picture of what might result from this 'barrage of poison'. It opened thus:

"There was once a small town in the heart of America where all life seemed to live in harmony with its surroundings...Then, a strange blight crept over the area and everything began to change...Everywhere was the shadow of death. The farmers spoke of much illness among their families".

But it was the imagined effect on our feathered friends that provided the basis for the book's title:

"It was a spring without voices. On the mornings that once throbbed with the dawn chorus...only silence lay over the fields and woods and marshes".

This mixture of science and poetical language might have made 'Silent Spring' anathema to fellow scientists, but it helped make the work much more engaging to the general public. Before Rachel's book came along, if corporations were attacked at all it was always criticisms of working conditions that they faced. 'Silent Spring' introduced another angle from which to attack the rapacious nature of some organisations, and that was from an environmental point of view that argued some products should be drastically reduced if not eliminated altogether. It also showed how 'the environment' was not something apart from people but rather something we are all intimately connected to.

THE BOOK'S CRITICS

But, as Silent Spring helped the environmental movement become broader in scope and attract a more diverse membership, the environmental movement lost the support of business and politicians who prioritised economic growth. Unlike her earlier books, which were all widely praised, Silent Spring created an uproar. Some of these attacks were ad-hominem in nature, such as those that did not address any content of the book but rather were aghast that a woman had spoken up. Dr. William Bean's comment in the 'Archives of Internal Medicine' was one such example. He wrote:

"Silent Spring, which I read word for word with some trauma, reminded me of trying to win an argument with a woman. It can't be done".

Other critics demonstrated a higher concern for money than the environment. A letter sent to the New Yorker reckoned, "Miss Rachel Carson's reference to the selfishness of insecticide manufacturers probably reflects her Communist sympathies...We can live without birds and animals, but, as the current market slump shows, we cannot live without business".

Perhaps the most reasonable arguments were those that pointed out an immediate detrimental effect if Rachel's call to drastically reduce pesticide use was put into effect. Silent Spring's case concerned the possible long-term effects-a century of use in fact-of extensive spraying. The companies that manufactured the stuff hit back with claims of what could happen if the insect population was not controlled. For example, the company Monsanto produced a pamphlet that satires Rachel's book. They called it 'Desolate Spring'.

"The bugs were everywhere, unseen, unheard...unbelievably universal...In every home...and, yes, inside man".

Even after years had passed since the book's publication, there were no peer-reviewed studies undertaken to show the book's critics were justified. The book never questioned DDT's effectiveness at killing insects, it was more of a doubt over the consequences for the environment as a whole. As we have seen, many critics focused on the more immediate financial cost of insecticide reduction, with one claiming "crop losses would probably soar to 50 percent, and food prices would increase four-fold to five-fold". But no measurements of yield and cost benefits were undertaken. Later longitudinal studies revealed that there had been large increases in crop yields from the early 1950s to the 1970s, but it's questionable whether this was entirely due to pesticides as claimed, and not a consequence of improvements to things like fertiliser, machinery, hybrid varieties of seed or irrigation.

THE TRAP

Something else began in the 1950s, and that was large-scale payment programs to farmers, the purpose of which was to reduce crop surpluses and provide price supports. In order to qualify for such subsidies, farmers removed arable land from cultivation. New synthetic pesticides made possible practices that would once have been regarded as foolhardy, such as working the remaining fields more intensely, and eliminating crop rotation and crop diversity. This actually encouraged the spread of pests, and as the pesticides did not distinguish between harmful and beneficial insects, predators that could have helped keep population sizes down were killed off. Not only were harmful insects surviving, they were also passing on their natural resistance to pesticides to the next generation, a clear example of evolution in action. Farmers found they were trapped in a self-defeating cycle, with little choice but to spray and to constantly seek out new types of insecticide with which to fight bugs resistant to current varieties.

RACHEL'S CANCER

The farmers were not the only ones engaged in a fight. Rachel had developed cancer, a fact that she fought to keep out of the public eye while she campaigned on environmental issues. It was on October 18, 1963, at Fairmount Hotel in California, that she gave her last public speech, one that emphasised how connected human beings are to the rest of nature. "We must never forget the wholeness of that relationship; nor can we think of the physical environment as a separate entity".

Only a month after that speech was delivered, an incident highlighted what could happen when such lessons go unheeded. Five million fish were found floating dead in the Mississippi. Following investigations by the US Public Health Service, it transpired that the chemical company, Veliscol Chemical Corporation, had been illegally dumping the pesticide Endrin into a wastewater treatment plant in Memphis. The company had previously joined in attacking Rachel's book, claiming it set out to "reduce the use of agricultural chemicals in this country and the countries of Western Europe, so that our supply of food will be reduced to east-curtain parity". By the 1980s, the EPA had banned pesticides like Endrin, and yet Veliscol continued to produce such pesticides for another decade for export, going as far as shipping to countries in which they were banned.

(Image from Wikipedia)

Rachel Carson did not live to see the EPA ban, she died of a heart attack on April 14 1964. But, as one of the most controversial environmentalists whose work helped popularise Green issues, she left behind quite a legacy.

REFERENCES

Wikipedia

'Blessed Unrest' by Paul Hawken

'Radical Evolution' by Joel Garreau

Good story my friend...

Downvoting a post can decrease pending rewards and make it less visible. Common reasons:

Submit

Very good story my friends....

Downvoting a post can decrease pending rewards and make it less visible. Common reasons:

Submit