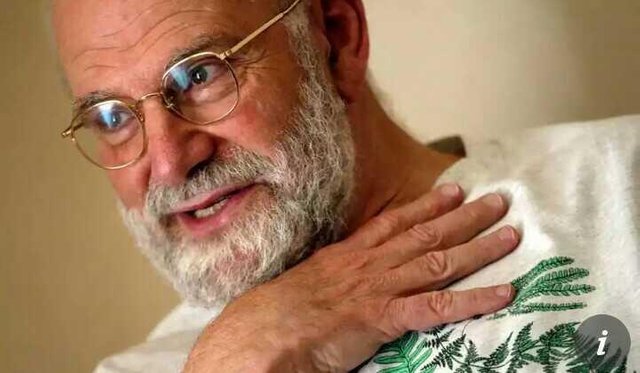

One March in the mid-1990s I checked into a cheap hotel in Helsinki. I dropped my bag on the floor and, wondering what kind of Finnish television was during the day, turned on the TV. The dark room with the dining table became the focus, and around it there were six people chatting. To my surprise, everyone speaks in English, then the face that I know fills the screen - it is Oliver Sacks. Then another, Stephen Jay Gould, and more, Daniel Dennett. I have books by all three. It was snowing outside, and Helsinki seemed suddenly less inviting; I sat on the bed and started watching.

A Dutch TV company has assembled these people, together with Freeman Dyson, Stephen Toulmin and Rupert Sheldrake, for a round table final of a documentary series on science and the meaning of life. The series, A Glorious Accident, did not seem to invite any women to take part, but nevertheless I watched it until the end - three hours later. The areas of expertise of participants vary: biology, physics, paleontology, neuroscience, philosophy. As the only practicing physician, Sacks makes perceptive and valuable contributions - and obviously has fun. I was just starting out in medicine, and I was relieved to see how lifelong clinical practice offers insights that are still relevant throughout science.

https://www.theguardian.com/books/2017/apr/06/insomniac-city-new-york-oliver-and-me-by-bill-hayes-review

Old years ago in August. Melanoma eye, which was diagnosed nine years earlier, has relapsed and metastasized to its heart. The New York Times has referred to Sacks as a "drug-winning poet," and has an obituary saying that his neurological condition is "for meditation that is eloquent about human consciousness and condition". In his final year he puts the finishing touches on a memoir (On the Move), and completes some of the last magazine essays collected soon after his death (Gratitude). In one of his last pieces of newspaper he wrote, "I have some other books that are almost done." We may wish that a further collection of posthumous essays will be present.

Millions of Sacks books have been printed all over the world, and he once talked about receiving 200 letters a week from admirers. For thousands of correspondents, the River of Consciousness will feel like a reprieve - we can spend more time with Sacks botanist, science historian, marine biologist, and of course, neurologist. There are 10 essays here, majority published earlier in New York Review of Books (this collection is dedicated to its late editor, Robert Silvers). Their subject reflects the agility of Sacks' enthusiasm, moving from forgetting and ignoring in science to Freud's early work on fish neuroanatomy; from the mental life of plants and invertebrates to the flexibility of our perception of speed.

https://www.theguardian.com/books/audio/2017/aug/15/living-with-oliver-sacks-and-love-in-later-life-bill-hayes-and-sylvia-brownrigg-podcast

The essay on speed has several evolving characteristics: Parkinson's disease, Sacks writes that "it is slowing down like being stuck in a peanut butter barrel, while in an accelerated state like being on ice". He is as good as the near-death experience: "There are intense feelings and intense realities, and accelerated thinking and perception and dramatic reactions." Sacks have the same respect as Jains for insects, and pleasure in comparative neuroanatomic facts: has six times more neurons than rats; many plants have a nervous system that moves one-thousandths of our own speed.

Sacks plagiarism is problematic, and memory essays fit in with creativity, checking how one can copy someone else's work through unwitting repatternings of memory. "Memory arises not just from experience," he concludes, "but from the relationship of many minds." He quotes letters between Mark Twain and Helen Keller about plagiarism, and his own correspondence with Harold Pinter (who plays A Kind of Alaska is inspired by Sacks's Awakenings). Most of his books are mentioned in passing, and the selected essays stand as a kind of testament or gazetteer. Reading them, I remembered something Annie Dillard had said about the essay form: "This essay, and has existed, all over the map. There's nothing you can not do with it; no material is prohibited, no structure is prohibited. "

Some of the lighter pieces here suffer from being placed among the more substantial jobs, and in one, only one, the Sacks argument loses coherence. But even then I was aware of the great premium he put on the flight of ideas: "If the flow of thought is too fast, he can lose himself, breaking into the flow of superficial disorder and tangent, dissolves in brilliant notoriety, a fantasmagoric, almost like a delirious dream. "

The sacks loved the details - with the irritation of the editor - and he stuffed his books with them. When the text can not retrieve it, it spills it to the bottom of the page. It is in the footnotes that his treasure is often to be found: in a two-page footnote for his essay "Scotoma: Forgetting and Ignoring Science", the sack outlines the urgent need for reconciliation between psychiatry and neurology, divided now for nearly a century. A "scotoma" is a blind spot in vision, a dark area that is bewitched by irregularities in the brain or retinal function:

If one looks at a patient chart institutionalized in a mental hospital and a state hospital in the 1920s and 1930s, one finds very detailed clinical and phenomenological observations, often embedded in narratives of near-dense wealth and density ... wealth and detail and this phenomenological openness has disappeared, and people find little notes that give no real picture of the patient or his world.

https://www.theguardian.com/books/2017/apr/06/insomniac-city-new-york-oliver-and-me-by-bill-hayes-review

Through the path of the 20th century, the US Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (a book prepared to facilitate health insurance bills) has, Sacks insists, poor clinical language. "The current psychiatric charts in the hospital are almost entirely devoid of the depth and density of information found in the old graphs, and will be of little use in helping us realize the synthesis of neuroscience with the psychiatric knowledge we need. "Earlier in the book he chose one of the defining moments of the division, when in 1893 Freud gave up looking for an element of brain pathology that might be relevant to mental health:" Lesions in hysterical paralysis should be completely independent of the nerves. system, "Freud wrote," because in paralysis and other hysteria manifestations behave as if anatomy does not exist or seems to have no knowledge of it. "

We still suffer the consequences of the division: the neurological dualism of life and health. It is estimated that about one-third of patients referred to neurological clinics have no "lesions" that can be tested or scanned. But their problem is not "all in their head" - a phrase that catches everything, does not mean that for many people it implies sickness or hypochondria. Functional disease does not exist, and modern psychiatry is nothing less than neurology that is tragically unprepared to deal with it. In that Helsinki hotel room, I saw Sacks come out of his training shed, and offer a more humane vision of what the fellowship of specialization can do. Two years after his death, he still reminds us that the same vision has long been delayed.

• Gavin Francis is a general practitioner and emergency. His Shapeshifters - On Human Life & Change will be published next year by Profile. To order The River of Consciousness for £ 13.15 (£ 18.99) go to the bookstore.theguardian.com or call 0330 333 6846. Free UK p & p over £ 10, online orders only. Min p & p phone orders from £ 1.99.