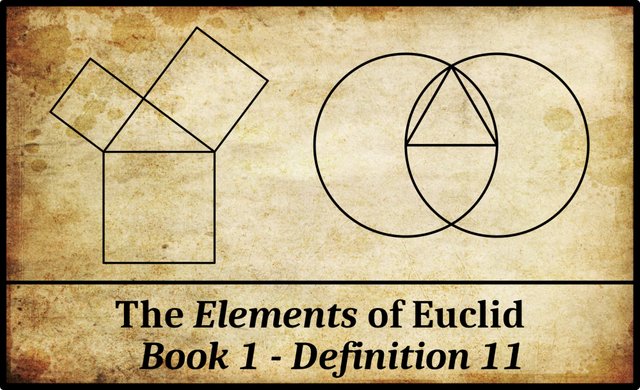

In Book 1 of Euclid’s Elements, Definition 11 reads (Fitzpatrick 6):

| Greek | English |

|---|---|

| ιαʹ. ̓Αμβλεῖα γωνία ἐστὶν ἡ μείζων ὀρθῆς. | 11. An obtuse angle is one greater than a right-angle. |

Euclid defines an obtuse angle in terms of a right-angle, which was defined in the preceding definition. As we have seen in the last few articles in this series, Euclid makes a distinction between the magnitude of an angle and its measurement. The latter is characterized by a number, but the magnitude of an angle is, as it were, a pre-numerate concept. In terms of magnitudes, one angle may be greater than, less than, or equal to another angle. In other words, angular magnitudes can be compared to one another, but without the metrical concept of numerical measurement we cannot be more specific than this. We cannot say, for example, that one angle is twice as big as another angle, or half as big.

An obtuse angle, therefore, is an angle whose magnitude is greater than that of a right-angle. Nothing is said about the metrical measurement of obtuse angles.

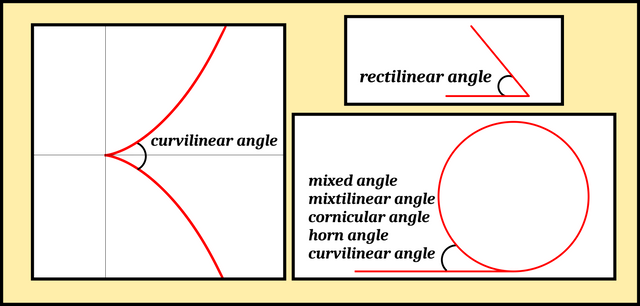

Note that Euclid does not specify that an obtuse angle be rectilinear. In Definition 9, Euclid introduced plane angles, which included not only rectilinear angles (ie angles as we usually understand them) but also curvilinear, mixtilinear, mixed and horn angles. These technical terms are used for different types of angles formed by the intersection of a line and a curve or by the intersection of two curves:

Note that there is no requirement that the angle be rectilinear; indeed, the horn angles mentioned before are not rectilinear, but they are less than right angles, and so are acute (notwithstanding Proclus’ remarks to the contrary). (Joyce)

There is little agreement in the literature concerning the precise definitions of these terms. The following are the definitions I am using:

Rectilinear Angle: an angle between two straight lines.

Mixtilinear or Mixed Angle: an angle between a straight line and a curve.

Curvilinear Angle: an angle between two curves. This is generally understood to mean the rectilinear angle between the tangents to the curves at the point of intersection. Confusingly, this term is sometimes used to describe a mixtilinear angle.

Horn Angle: a mixtilinear angle between a circle and one of its tangents. A horn angle is also called a cornicular angle.

All horn angles are smaller than right angles, but some curvilinear angles are greater than right angles. As Joyce indicates, the 5th-century philosopher Proclus amended Euclid’s tenth and eleventh definitions to exclude all such non-rectilinear angles from the two categories of obtuse and acute angles:

To the definitions of the obtuse and acute angles we must add the genus: each of them is rectilinear, one larger and the other smaller than a right angle. Not every angle smaller than a right angle is acute, for the horned angle is smaller than any right angle—indeed smaller than any acute angle—but is not acute; and likewise the semicircular angle is smaller than any right angle but is not acute. The explanation is that these are mixed, not rectilinear angles. Clearly also many angles contained between circular lines appear to be greater than right angles, but they are not for that reason obtuse; for the obtuse angle must be rectilinear. (Morrow 107-108)

It is not clear from Definitions 11 and 12 whether Euclid intends to restrict these two categories to rectilinear angles. As Proclus points out, he does not specify that obtuse or acute angles be plane angles, though most commentators agree that this is implied (Morrow 108-109). It makes sense, then, that rectilinearity is also implied even though it is not explicitly stated.

In Proclus’ defence, it is only fair to add that throughout the Elements Euclid uses the terms obtuse and acute only with reference to rectilinear angles.

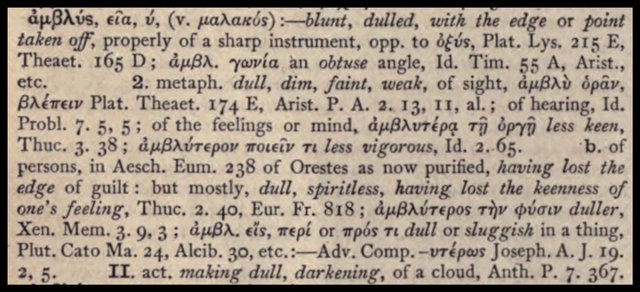

Terminology

The Greek word Euclid uses for obtuse is ἀμβλεῖα [ambleia]. This is the feminine nominative singular form of the adjective αμβλύς [amblus], which means blunt, dull, obtuse. In ancient Greek, the word was used in the literal sense (eg a blunt tool), the figurative sense (eg dull of sight or hearing), and the geometric sense (ie an obtuse angle):

And that’s a good place to stop.

References

- Richard Fitzpatrick (translator), Euclid’s Elements of Geometry, University of Texas at Austin, Austin, TX (2008)

- Thomas Little Heath (translator & editor), The Thirteen Books of Euclid’s Elements, Second Edition, Dover Publications, New York (1956)

- Johan Ludvig Heiberg, Heinrich Menge, Euclidis Elementa edidit et Latine interpretatus est I. L. Heiberg, Volumes 1-5, B G Teubner Verlag, Leipzig (1883-1888)

- Henry George Liddell, Robert Scott, A Greek-English Lexicon, Eighth Edition, American Book Company, New York (1901)

- Glenn R Morrow (translator), Proclus: A Commentary on the First Book of Euclid’s Elements, Princeton University Press, Princeton, NJ (1970)

Online Resources