In the preceding article in this series, I tentatively identified the Thirty-Third Station of the Exodus, Kadesh, with the ancient city of Petra in Jordan. According to the itinerary being proposed in these articles, the ancient Israelites proceeded from the Fourteenth Station, Hazeroth (‘Ain el-Hudhera), straight to Kadesh.

The Thirty-Second Station, the one immediately before Kadesh, is Ezion-Geber. This well-known place lay at the northern extremity of the Gulf of Aqaba, about 90 km from ‘Ain el-Hudhera and 100 km from Petra—as the crow flies. More realistically, though, the distances for a caravan travelling on foot are around 120 km from Hazeroth to Ezion-Geber and another 120 km from there to Petra.

In Numbers 33, the Catalogue of the Stations of the Exodus identifies seventeen stations between Hazeroth and Ezion-Geber, but none between Ezion-Geber and Kadesh: Hazeroth, Rithmah, Rimmon-Perez, Libnah, Rissah, Kehelathah, Mount Shapher, Haradah, Makheloth, Tahath, Tarah, Mithcah, Hashmonah, Moseroth, Bene-Jaakan, Hor Haggidgad, Jotbathah, Abronah, Ezion-Geber, Kadesh.

In the previous article, we saw how Goethe surmised that the stations between Hazeroth and Kadesh were fictitious. Other than Ezion-Geber, none of these places has ever been identified definitively (though, as we shall see, there are convincing candidates for Jotbathah and Abronah). But were they all fictitious?

If the Israelites were covering approximately 24-32 km per day (Hoffmeier 120), then the journey from Hazeroth to Kadesh must have taken them about 7-10 days. If it took them seven days, then the journey from the Twelfth Station, the Mountain of God, to Kadesh would have taken a total of eleven days—as specified by Deuteronomy 1:1-2—as it took them three days to reach the Thirteenth Station, Kibroth-Hattaavah, from the Mountain (Numbers 10:33), and, presumably, one day to reach Hazeroth from Kibroth-Hattaavah.

The Israelites, therefore, must have camped overnight about half-a-dozen times between Hazeroth and Kadesh. If Ezion-Geber was one of these encampments, then there were probably two or three stations between Hazeroth and Ezion-Geber and another two or three between Ezion-Geber and Kadesh. Do any of the seventeen stations listed in Numbers 33 correspond to these? That is one of the questions I hope to explore in this article and the following article.

Deuteronomy 10

In The Book of Deuteronomy, Moses recounts to the Israelites how he acquired the two Tablets of the Law on the Mountain of God and what transpired thereafter:

At that time the Lord said unto me, Hew thee two tables of stone like unto the first, and come up unto me into the mount, and make thee an ark of wood. And I will write on the tables the words that were in the first tables which thou brakest, and thou shalt put them in the ark. And I made an ark of shittim wood, and hewed two tables of stone like unto the first, and went up into the mount, having the two tables in mine hand. And he wrote on the tables, according to the first writing, the ten commandments, which the Lord spake unto you in the mount out of the midst of the fire in the day of the assembly: and the Lord gave them unto me. And I turned myself and came down from the mount, and put the tables in the ark which I had made; and there they be, as the Lord commanded me.

And the children of Israel took their journey from Beeroth of the children of Jaakan to Mosera: there Aaron died, and there he was buried; and Eleazar his son ministered in the priest’s office in his stead. From thence they journeyed unto Gudgodah; and from Gudgodah to Jotbath, a land of rivers of waters. (Deuteronomy 10:1-7)

The first thirty chapters of Deuteronomy are devoted to three lengthy sermons delivered by Moses on the plains of Moab, to the east of the River Jordan, shortly before the Conquest of Canaan. What are we to make, then, of Beeroth of the Children of Jaakan, Mosera, Gudgodah and Jotbath? These are generally identified with four consecutive Stations of the Exodus listed in Numbers 33: Moseroth, Bene-Jaakan, Hor Haggidgad, Jotbathah. Their independent appearance in Deuteronomy suggests that they may be genuine stations and not later interpolations. Nevertheless, their identities remain uncertain. Note also that Deuteronomy 10 has Beeroth of the Children of Jaakan before Mosera, while Numbers 33 lists Moseroth before Bene-Jaakan. This supports the view that this section of the Catalogue of Stations has suffered corruption.

Ezion-Geber

Before proceeding, let us be sure that Ezion-Geber itself has been correctly identified. As we saw in the preceding article, none of the many places that have been identified with Kadesh lies within 32 km of Eilat or Aqaba, the modern cities in whose vicinity Ezion-Geber is thought to have stood. But the Catalogue of the Stations of the Exodus in Numbers 33 does not enumerate any stations between Ezion-Geber and Kadesh, suggesting that the journey from the former to the latter was accomplished in a single day.

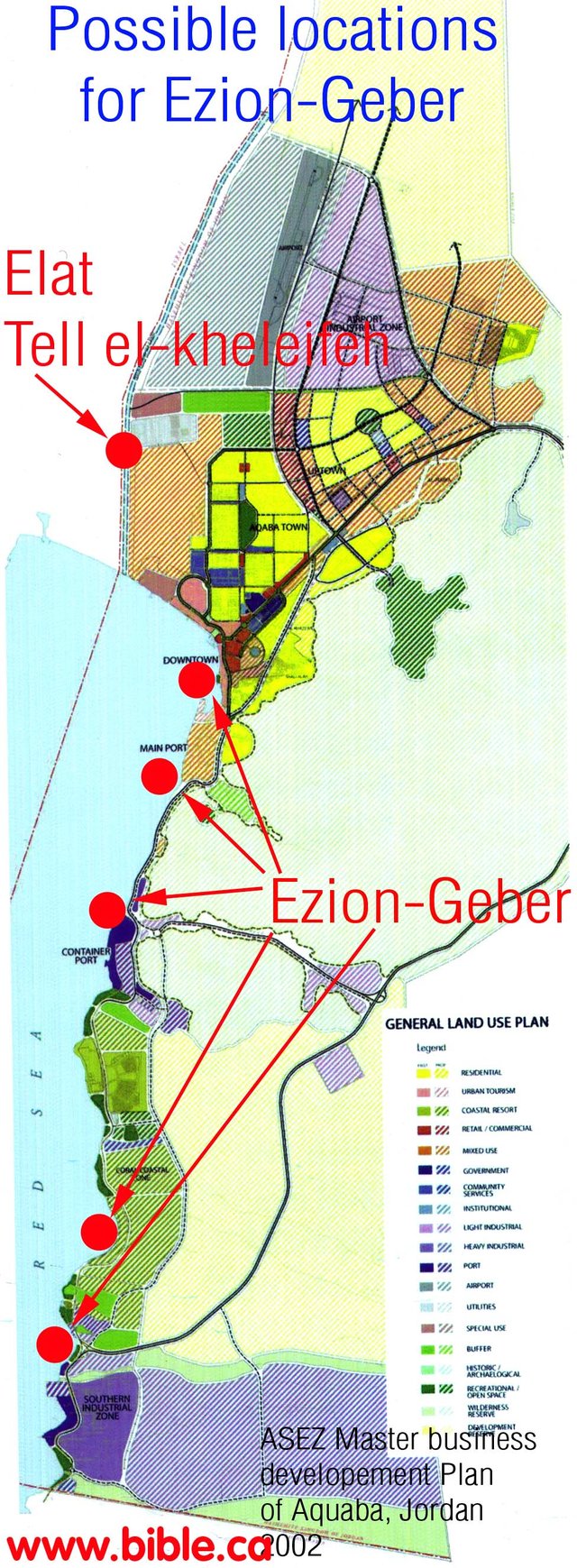

One popular theory, first proposed in 1933 by Fritz Frank, is that Tell el-Kheleifeh, which lies between Eilat and Aqaba is Ezion-Geber. Nelson Glueck was the first to excavate Tell-el-Kheleifeh (1938-1940). A quarter of a century later he reconsidered the matter but did not abandon the identification with Ezion-Geber:

[We] have begun reviewing the Tell el-Kheleifeh excavation records. We find ourselves compelled in their light and in view of new knowledge and some convincing criticisms of our initial reports to revise radically some of our original conclusions ... In any event, the occupational history of Tell el-Kheleifeh encompasses the histories both of Ezion-geber and Elath as delineated in the Bible ... (Glueck 71-72 ... 85)

Independent researcher Steve Rudd of Bible Archeology has suggested that the true location of Ezion-Geber lies on the eastern side of the Gulf of Aqaba, just south of Aqaba. He has indicated five potential sites, the most northerly of which is about 4 km south of central Aqaba, and the most southerly about 22 km further south. Rudd believes that the Israelites approached Ezion-Geber from the south-east (Midian), having crossed the Gulf of Aqaba near the southern tip of Sinai, so these sites make perfect sense.

If, however, the Israelites were making their way to Canaan from Sinai, it would have made no sense for them to turn south after reaching the head of the Gulf of Aqaba.

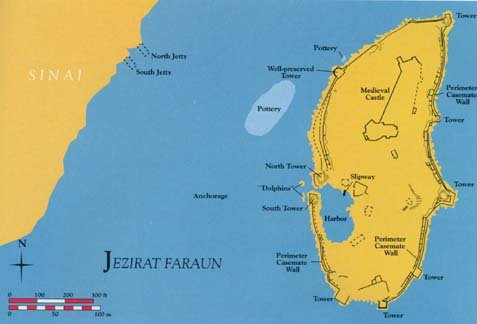

Other researchers have suggested that Ezion-Geber lay at Jezirat Faraun, or Pharaoh’s Island, a small island about 11 km southwest of Eilat. One of the pioneers of submarine archaeology, Alexander Flinder, supported this identification:

Even if Glueck’s identification of the [Tell el-Kheleifeh] had remained unchallenged on metallurgical grounds, his theory was seriously flawed on maritime grounds. The coastline at Tell el-Kheleifeh is a sandy beach with shallow water—totally unsuitable for small craft, let alone for a substantial merchant fleet. It is inconceivable that Hiram’s naval commanders [I Kings 9] would have given this site a second glance. It could not have been used as a port. (Flinder 31-43)

In 1967, Flinder visited the site at Pharaoh’s Island and explored its underwater remains. He was impressed by what he saw:

On the sea bed we found a quantity of Late Roman/Byzantine pottery (330-640 A.D.). More pertinent, I was struck by how still the sea was in the area between the island and the mainland. It remained comparatively calm even when the open sea to the east of the island was choppy. Any sailor would immediately recognize the area between the island and the shore as a natural anchorage. Much later, I found a 1909 British sailing chart for the Gulf of Aqabah that identifies this area as the “Faraun Island Anchorage.” Several 19th-century travelers also observed that this was the only natural anchorage in the entire northern part of the gulf. The modern ports of Eilat and Aqabah, by contrast, are wholly artificial constructions. (Flinder 31-43)

Further exploration convinced Flinder that there had once been a small harbour on the island:

One feature in particular affected and directed all my future thinking. On the southwestern edge of the island, in a low area between the two southern hills, there is a pool, identified by Rothenberg and Hashimshoni as a harbor. A bar separates this pool from the natural anchorage. On close examination, I found that this bar was an integral part of the perimeter wall. Only a narrow channel linked the pool to the sea. Masonry blocks lined this channel, and on each side of the channel there was the base of a tower. The pool was not a natural body of water, but was indeed an artificially constructed boat basin—a small harbor! (Flinder 31-43)

Dating the site has proved difficult:

Now we must turn to the difficult problem of dating. In the absence of a systematic excavation, the dating of the perimeter wall, as well as the harbor and jetties, must be conjectural. Some scholars have expressed the view that these structures are all Byzantine, but it is not implausible that they belong to earlier periods of occupation. Pottery found on the island by Rothenberg in 1972 and a small quantity collected by us in 1968 has been dated to Iron Age I (1200-930 B.C.) Rothenberg's excavation of the Hathor (Khat-KHOR) Temple at Timnah,16 [miles] north of Eilat, has produced evidence of an Egyptian mining operation in the Late Bronze/Early Iron Age I (14th-12th centuries B.C.).

From this Rothenberg has concluded that the island was an Egyptian mining harbor of the Ramessid pharaohs. Rothenberg also points to the remains of a small metallurgical installation on the island, as well as a quantity of fayalite stag (an iron-based silicate), evidence of small-scale iron-smelting activities on Jezirat Faraun.

Can we say that this is Ezion-Geber of Solomonic times? The firm dating evidence has not yet been found. What we can say is that there was an impressive maritime installation of considerable complexity at Jezirat Faraun: a fortified island with an enclosed harbor adjoining a large natural anchorage, with jetties located opposite the island on the mainland. (Flinder 31-43)

These dates are conventional, of course, but the Late Bronze Age and Iron Age I encompass the historical period to which the Exodus belongs.

Wherever Ezion-Geber lay, the important point is that everyone seems to agree that it was somewhere in the vicinity of the northern end of the Gulf of Aqaba. Let us accept this, then, as a given. It leaves unresolved the conundrum of Numbers 33, which has Ezion-Geber listed immediately before Kadesh. I can only surmise that this section of the catalogue is defective. This would lend support to Goethe’s theory that the thirty-eight years of wandering in the wilderness, which allegedly followed the arrival at Kadesh and preceded the conquest of Canaan, were a later interpolation.

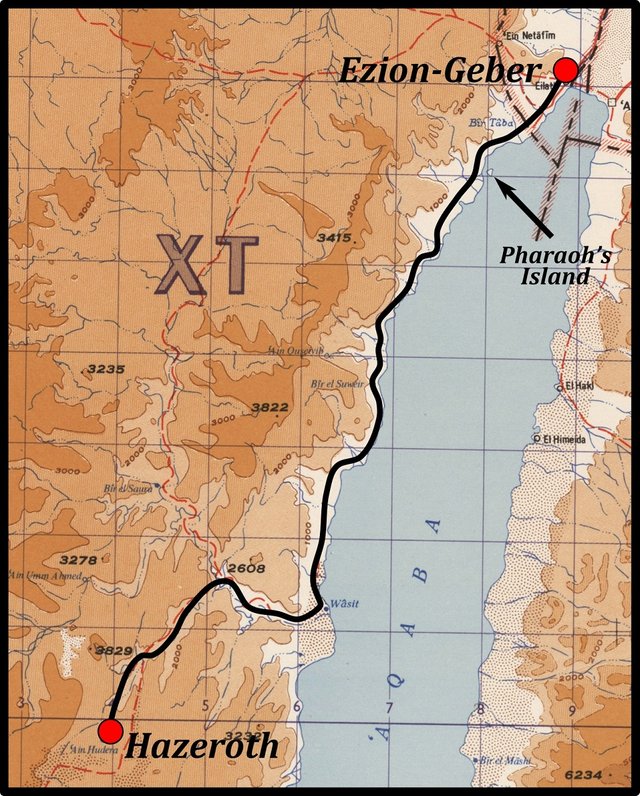

From Hazeroth to Ezion-Geber

What route did the Israelites follow between ‘Ain el-Hudhera and Ezion-Geber? The account in Numbers does not specify any route. Kenneth Kitchen, who investigated this question in On the Reliability of the Old Testament concluded that the Israelites proceeded along the coast. He assessed four possible routes for the Exodus out of Egypt, finally opting for the Southern Route:

That brings us to the remaining option: down Sinai’s west coastlands, then east through the mountains and wadis to a Southern Mount Sinai, then back up northeastward by Sinai’s east coast and desert to Qadesh-Barnea. (Kitchen 268)

Although Kitchen’s analysis does not agree with mine as to the location of the Mountain of God (Horeb/Sinai), he does identify ‘Ain el-Hudhera with Hazeroth (Kitchen 272):

The eleven days from about Wadi es-Sheikh (Horeb/Sinai zone) to Qadesh-Barnea would correspond quite well to roughly 140 miles [220 km] up Sinai’s east side (via Hazeroth) at a rate of twelve-thirteen miles (19-21 km) per day. The further names in Num 33:19-35 cannot be placed. (Kitchen 273)

As Ezion-Geber lay on the coast somewhere near the head of the Gulf of Aqaba, it would have been natural for the Israelites to proceed from ‘Ain el-Hudhera to the coast, and then follow the coast all the way to Ezion-Geber—just as Kitchen proposes. If, then, there were two or three encampments between Hazeroth and Ezion-Geber, it is along this coastal route that they are probably to be found.

The Coastal Route

The route indicated on the map above is approximately 120 km long. For the most part, this route is flat and undemanding, which would have allowed the Israelites to travel faster than Hoffmeier’s upper limit of 32 km per day. So they may have been able to accomplish the journey from Hazeroth to Ezion-Geber in as little as three days and surely no more than four. We can conclude, therefore, that there were probably two or three stations along this road—two if Ezion-Geber was at Pharaoh’s Island.

A glance at a detailed map of this region, however, fails to throw up any obvious parallels with any of the seventeen Stations of the Exodus that follow Hazeroth. At least one candidate has been suggested, however:

[But] the 6th station from Hazeroth was at Mt. Shepher (Nu 33 23), and may have left its name corrupted into Tell el-‘Aṣfar (or ‘Asfar), the Heb. meaning “the shining hill,” and the Arab. either the same or else “the yellow.” This site is 60 miles [95 km] from Hazeroth, giving a daily march of 10 miles [16 km]. (Orr 3067)

This Tell el-‘Asfar lies about 10 km north of the head of the Gulf of Aqaba, so if this identification is correct, then this could only have been one of the stations after Ezion-Geber. Orr’s 60 miles is as the crow flies. On foot, the distance from Hazeroth is more like 130 km.

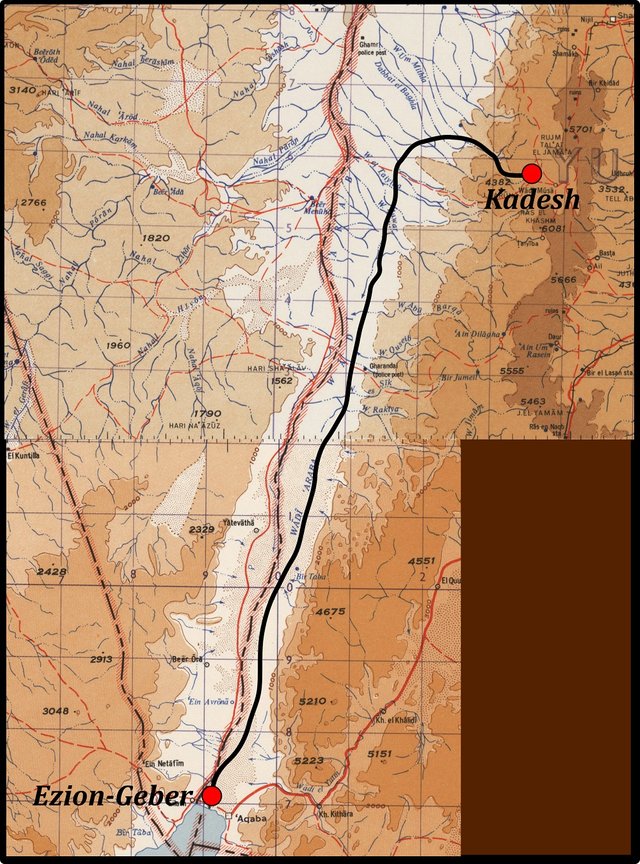

From Ezion-Geber to Kadesh

The simplest route from Ezion-Geber to Kadesh—assuming that the latter was Petra—follows the lowlying Arabah for about 90 km, before turning east and ascending one of the local wadis to Petra. The total distance of this route is around 120 km—or 130 km if Ezion-Geber was at Pharaoh’s Island.

About 12 km north of Eilat is the well of ‘Ein Avrōnā. Could this be the 31st Station of the Exodus Abronah? In Numbers 33, this is listed as the station immediately before Ezion-Geber, but if this section of the catalogue has suffered corruption, then perhaps Abronah was originally the station immediately after Ezion-Geber. (Recall how Moseroth and Bene-Jaakan of Numbers 33 are listed in the opposite order in Deuteronomy 10 as Beeroth of the Children of Jaakan and Mosera.)

The principal objection to the identification of ‘Ein Avrōnā with Abronah is that 12 km is too short a distance for a whole day’s march—especially over flat and easy terrain. But if Ezion-Geber was located at Pharaoh’s Island, then this leg of the journey would have been about 24 km long, which is at the lower end of Hoffmeier’s range and a little further than Kitchen’s upper limit.

About 22 km north of ‘Ein Avrōnā is a place called Yātevāthā, or Yotvata. In the Catalogue of Stations in Numbers 33, the station immediately before Abronah is called Jotbathah. Could this be Yātevāthā, making it the station immediately after Abronah? 22 km is a reasonable distance to be covered in a single day. It is somewhat less than Hoffmeier’s lower estimate of 24 km per day, but still greater than Kitchen’s upper limit of 21 km.

This is as far as we can go. If we continue this pattern of taking the stations in Numbers 33 in reverse order, we will not come across any other toponyms in the Arabah that resemble any of the remaining stations enumerated in Numbers 33 between Hazeroth and Kadesh:

As regards the other stations, Rithmah means “broomy,” referring to the white desert broom; rimmon-perez was a “cloven height,” and Libnah a “white” chalky place; Rissah means “dewy,” and Kehelathah, “gathering.” From Mt. Shepher the distance to the vicinity of Mt. Hor is about 55 miles [90 km], and seven stations are named, giving an average march of 8 miles [per day]. the names are Haradah (Nu 33 24), “fearful,” referring to a mountain; Makheloth, “gatherings”; Tahath—probably “below”—marking the descent into the ‘Arabah; Terah, “delay,” referring to rest in the better pastures; Mithkah, “sweetness” of pasture or of water; Hashmonah, “fatness”; and Moseroth, probably meaning “the boundaries,” near Mt. Hor. These names, though now lost, agree well with a journey through a rugged region of white limestone and yellow sandstone, followed by a descent into the pastoral valley of the ‘Arabah. The distances are all probable for flocks. (Orr 3067-3068)

Claude Reignier Conder has suggested some candidates for the stations between Ezion-Geber and Kadesh, though for the most part they strike me as wholly arbitrary. Only one can be considered even remotely convincing:

Of the stations in the Arabah, where Israel dwelt during the rest of the forty years, less is known. Gudgodah is probably the present Ghadaghit—a valley some twenty miles (32 km) west of Mount Hor. (Conder 48-49)

Conder identifies Mount Hor with Jebel Harun, which lies close to Petra. Perhaps this Ghadaghit was the final station before Kadesh? I haven’t found any such place as Ghadaghit on any of the maps that I have consulted, so I have to take Conder’s word for it.

Conclusions

Tentatively—as usual—the following conclusions may be drawn:

Ezion-Geber was located somewhere at the head of the Gulf of Aqaba. Its precise location is still uncertain, but I am inclined to favour Pharaoh’s Island—if only because ‘Ein Avrōnā lies about 24 km away, which is far enough to have required a full day’s march to reach it from Ezion-Geber.

Tell el-‘Asfar is possibly to be identified with the 20th Station of the Exodus, Mount Shapher.

Ghadaghit is possibly to be identified with the 29th Station, Hor Haggidgad, or Gudgodah.

‘Ein Avrōnā is probably to be identified with the 31st Station, Abronah.

Yotvata is probably to be identified with the 30st Station, Jotbathah.

The Catalogue of the Stations of the Exodus in Numbers 33 is corrupt after Hazeroth.

To be continued ...

References

- Claude Reignier Conder, The Bible and the East, William Blackwood and Sons, Edinburgh (1896)

- Alexander Flinder, Is this Solomon’s Seaport?, Biblical Archaeology Review, Volume 15, Number 4, pp 31-43, Biblical Archaeology Society, Washington DC (1989)

- Nelson Glueck, Ezion-Geber, The Bible Archaeologist, Volume 28, Number 3, pp 69-87, The University of Chicago Press (1965)

- Johann Wolfgang von Goethe, Israel in der Wüste, Noten und Abhandlungen zu besserem Verständnis des west-östlichen Divans, West-östlicher Divan, in Erich Trunz (editor), Goethes Werke, Band 2, Fifth Edition, Christian Wegner Verlag, Hamburg (1960)

- James K Hoffmeier, Ancient Israel in Sinai: The Evidence for the Authenticity of the Wilderness Tradition, Oxford University Press, Oxford (2005)

- Kenneth A Kitchen, On the Reliability of the Old Testament, William B Eerdmans Publishing Company, Grand Rapids MI (2003)

- James Orr (General Editor), The International Standard Bible Encyclopedia, Volume 5, The Howard-Severance Company, Chicago (1915)

Image Credits

- Moses Preaches to the Israelites on the Plains of Moab: Phillip Medhurst (artist), The Phillip Medhurst Collection, Belgrave Hall, Leicester, © Philip De Vere, Creative Commons License

- Eilat: © Ferrell Jenkins (photographer), Fair Use

- Candidate Sites for Ezion-Geber (Rudd): © Steve Rudd, Fair Use

- Jezirat Faraun (Pharaoh’s Island): © 2019 Biblical Archaeology Society, Fair Use

- Pharaoh’s Island: © Omar Salah Hassan (photographer), Creative Commons License

- The Western Sinai Peninsula: University of Texas Libraries, Perry-Castañeda Library Map Collection, Aqaba, Suez, D Survey, Great Britain War Office and Air Ministry (1960), Public Domain

- ’Ein Avrōnā: © Uzi Avner (photographer), Fair Use

- Yotvata: © Gordio (photographer), Creative Commons License