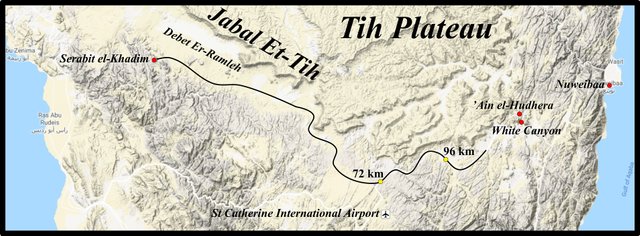

In the preceding article in this series, we postulated that the Thirteenth Station of the Exodus—whether it was called Taberah or Kibroth Hattaavah, or even Paran—lay 72-96 km from Serabit el-Khadim, somewhere along the modern road between St Katherine International Airport and White Canyon. ’Ain el-Hudhera, which is traditionally identified with the Fourteenth Station of the Exodus, Hazeroth, lies about 1 km north of White Canyon.

If Hazeroth was ’Ain el-Hudhera and if the Israelites were covering 24-32 km per day (Hoffmeier 120), then Kibroth Hattaavah would need to be located closer to the 96-km mark, which lies about 27 km from ’Ain el-Hudhera. Unfortunately, this does not help us to identify this station. No modern toponyms in this region bear any resemblance to Taberah, Kibroth Hattaavah or Paran. The best I can do is quote Edward Henry Palmer, who claimed to have discovered the remains of an ancient encampment in this region:

A little further on, and upon the watershed of Wady el Hebeibeh, we came to some remains which, although they had hitherto escaped even a passing notice from previous travellers, proved to be among the most interesting in the country. The piece of elevated ground which forms this watershed is called by the Arabs Erweis el Ebeirig, and is covered with small enclosures of stones. These are evidently the remains of a large encampment, but they differ essentially in their arrangement from any others which I have seen in Sinai or elsewhere in Arabia; and on the summit of a small hill on the right is an erection of rough stones surmounted by a conspicuous white block of pyramidal shape. The remains extend for miles around, and, on examining them more carefully during a second visit to the Peninsula with Mr Drake, we found our first impression fully confirmed, and collected abundant proofs that it was in reality a deserted camp. The small stones which formerly served, as they do in the present day, for hearths, in many places still showed signs of the action of fire, and on digging beneath the surface we found pieces of charcoal in great abundance. Here and there were larger enclosures marking the encampment of some person more important than the rest, and just outside the camp were a number of stone heaps, which, from their shape and position, could be nothing else but graves. The site is a most commanding one, and admirably suited for the assembling of a large concourse of people.

Arab tradition declares these curious remains to be “the relics of a large Pilgrim or Hajj caravan, who in remote ages pitched their tents at this spot on their way to ’Ain Hudherah, and who were soon afterwards lost in the desert of the Tih, and never heard of again.”

For various reasons I am inclined to believe that this legend is authentic, that it refers to the Israelites, and that we have in the scattered stones of Erweis el Ebeirig real traces of the Exodus ... the distance—exactly a day’s journey—from ’Ain Hudherah, and those mysterious graves outside the camp, to my mind prove conclusively the identity of this spot with the scene of that awful plague by which the Lord punished the greed and discontent of His people (Palmer 257-260)

A recent archaeological expedition has dated the remains at Erweis el Ebeirig to the Early Bronze Age II (Beit-Arieh). Forgive me if I have little faith in the dates quoted by mainstream archaeologists.

According to Louis Ginzberg’s The Legends of the Jews, the Israelites covered an eleven days’ distance during their three days’ march from the Mountain of God to Kibroth Hattaavah, but I think we can dismiss this as more myth than legend (Ginzberg 243).

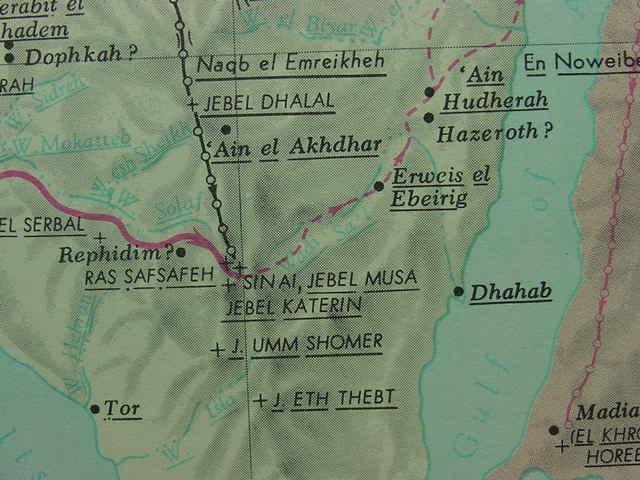

Before proceeding to the Fourteenth Station of the Exodus, Hazeroth, we must examine the claim that the true location of Kibroth Hattaavah is actually indicated by ancient inscriptions to the south of Serabit el-Khadim.

Turbet es Yahoud

In 1753, a controversial Irish bishop called Robert Clayton delivered an address to the Society of Antiquaries in London entitled A Journal from Grand Cairo to Mount Sinai, and Back Again. The work included a translation of a manuscript written by the Franciscan Prefect of Egypt, which described a pilgrimage made in 1722 by a group of Franciscans from Cairo to Mount Sinai. On this journey, the monks came across many inscriptions, which subsequently—ie after they had been translated—seemed to corroborate many of the events of the Exodus. In fact, the region was so replete with inscriptions that the surrounding mountains were still known to the local Arabs as Gebel el Mokatab:

These hills are called Gebel el-Mokatab, that is, The written mountains: For as soon as we had parted from the mountains of Faran we passed by several others for an hour together, engraved with ancient unknown characters, which were cut into the hard marble rock so high as to be in some places at twelve or fourteen feet distance from the ground: and though we had in our company persons, who were acquainted with the Arabic, Greek, Hebrew, Syriac, Coptic, Latin, Armenian, Turkish, English, Illyrican, German and Bohemian languages, yet none of them had any knowledge of these characters; which have nevertheless been cut into the hard rock with the greatest industry, in a place where there is neither water, nor any thing to be gotten to eat. It is probable therefore these unknown characters contain some very secret mysteries, and that they were engraved either by the Chaldeans, or some other persons long before the coming of Christ. (Clayton 45-46)

These inscriptions had first been brought to the attention of the scholarly world by the 6th-century Alexandrian merchant Cosmas Indicopleustes, but they had been subsequently forgotten until Clayton and the Franciscans brought them back into vogue.

In 1761, the German antiquary and explorer Carsten Niebuhr visited Sinai as part of the Danish Arabia Expedition. He documented his experiences in Reisebeschreibung nach Arabien und andern umliegender Ländern [Travels in Arabia and Other Neighbouring Countries], which appeared in three volumes in 1774, 1778 and (posthumously) 1837. In the first volume, he describes how he and his colleagues climbed a certain Gebel Mukattab, supposedly the mountain peak of that name about 20 km south of Serabit el-Khadim, in the hope of examining some of the inscriptions recorded by the Franciscans almost forty years before:

This mountain is so tall and precipitous that we were obliged to leave our camels at the bottom; it took us more than an hour and a half to climb to the summit. After much difficulty we reached our goal, thinking that we would finally find the inscriptions, engraved on the rock itself. But we were not a little surprised to see a superb Egyptian cemetery in the middle of the desert, and atop such a steep-sided mountain; I say Egyptian cemetery because I am persuaded that this is what every European would call it, even though nothing like it is to be seen in Egypt, where time has buried most of the ancient monuments in the sand. In this spot, a multitude of stones are to be seen, some still standing, some toppled or broken; they are five to six feet in length, and six inches to two feet in width; they are covered with Egyptian hieroglyphs; they can only have been grave stones. (Niebuhr 189)

Niebuhr was a little disappointed to discover that the inscriptions which were to be found in the surrounding areas—such as in the Wadi Mukattab—were not nearly as old as the hieroglyphs he found at the summit of Gebel el-Mukattab:

This Gebel el Mokattab bears no resemblance to that which has been described by the Franciscans in Cairo; but it seems to be all the more remarkable, especially as it has been almost proved that the inscriptions which are to be found all over these mountains are neither ancient nor particularly fine, and were in fact only engraved by travellers; whereas the hieroglyphs of which I have spoken are quite as fine as those of Egypt. This shows that the arts flourished in this land as in Egypt, and that there was an opulent city somewhere in the vicinity—unless one can prove that certain inhabitants of Egypt, who did not preserve their deceased loved ones as mummies, held this place in the desert in particular veneration, and for this reason brought their dead here. (Niebuhr 191)

It appears, however, that what Niebuhr took to be the Franciscans’ Gebel Mukattab was actually Serabit el-Khadim itself. Niebuhr assumed that the stelae were gravestones. He suspected that his guides had misled him:

Following the description of another Gebel el Mokattab, which it is claimed is in this area, and which was actually the one we were looking for, we judged that it would take a whole month just to copy the inscriptions with which it was said to be covered: whereas a single day sufficed to satisfy our curiosity concerning the Gebel el Mokattab to which we had actually been led. (Niebuhr 191-192)

With time running out, Niebuhr’s expedition pushed on to Mt Sinai instead. Whatever the true identity of the Gebel Mukattab he climbed, he was nevertheless prepared to accept that the “graves” on the summit, which the local Bedouin allegedly called Turbet es Yahoud, or Graves of the Jews, could date back to the time of the Exodus:

Were not these perhaps the Sepulchres of lust [Kibroth Hattaavah] mentioned in Numbers 11:34, or the Mount of Horeb spoken of in Numbers 33:38? Whether this was a cemetery of the Israelites or of the ancient inhabitants of this land, it continues to furnish scholars with ample matter for speculation. (Niebuhr 191)

Decipherment

Interest in the widespread inscriptions of Sinai grew in the 19th century, as the successful decipherment of Egyptian hieroglyphs and other ancient scripts finally allowed them to be read. In 1840 one of the first fruits of these successes appeared, Eduard Friedrich Ferdinand Beer’s Studia Asiatica, the third volume of which included transcriptions and Latin translations of several of the Sinaitic inscriptions. In 1854 Charles Forster brought out a study of the inscriptions, which is altogether more accessible to the English reader, and includes a critique of Beer’s work.

Unlike Beer, Forster believed that the inscriptions confirmed many of the details of the Exodus narrative in the Bible:

Among the events of the Exode these records comprize, besides the healing of the waters of Marah, the passage of the Red Sea, with the introduction of Pharaoh twice by name, and two notices of the Egyptian tyrant’s vain attempt to save himself, by flight on horseback from the returning waters; together with hieroglyphic representations of himself, and of his horse, in accordance with a hitherto unexplained passage of the Song of Moses: “For the horse of Pharaoh went into the sea, and the Lord brought again the waters of the sea upon them:” they comprize, further, the miraculous supplies of manna and of flesh: the battle of Rephidim, with the mention of Moses by his office, and of Aaron and Hur by their names; the same inscription repeated, describing the holding up of Moses’s hands by Aaron and Hur, and their supporting him with a stone, illustrated by a drawing, apparently, of the stone, containing within it the inscription, and the figure of Moses over it with uplifted hands: and lastly, the plague of fiery serpents, with the representation of a serpent in the act of coming down, as it were from heaven, upon a prostrate Israelite. (Forster 61-62)

On the face of it, this seems to provide striking proof not only of the historicity of the Exodus but also of the plague described in Numbers 11, which was caused by the eating of quail. The problem I have with these inscriptions, however, is that they bear all the appearance of having been added long after the Exodus, perhaps with the explicit intention of corroborating the Scriptures. For example:

Some of the inscriptions employ an alphabetic script, which is considerably more advanced than the Proto-Sinaitic inscriptions found in the vicinity of Serabit el-Khadim.

Moses’ brother Aaron is mentioned, even though his historicity is highly questionable (Singer 5).

Some of the inscriptions mention explicitly the dividing of the Red Sea, the drowning of the Egyptians, and the plague caused by eating quail. While there may well be a historical basis to these events, the Biblical accounts are probably replete with unhistorical details.

The plague of fiery serpents occurred at the end of the Forty Years of Wandering at Kadesh Barnea, which is generally sought somewhere to the south of Canaan. How, then, could the Israelites have recorded this episode in a wadi in the west of the Sinai Peninsula?

These doubts are shared by mainstream academics, who attribute the inscriptions to Nabataean Arabs—though it is still debated whether these were local residents or merely transient visitors (see Avner for further comment).

I have made this digression because these inscriptions are still cited as corroboration of the Exodus narrative. There is an abundance of evidence that leads me to believe that the Exodus narrative is based on some kernel of historical truth, but these inscriptions are not part of that evidence. They are the relics of Nabataean pilgrims to the traditional sites of the Exodus in the Sinai Peninsula. They can only be cited as evidence that in the late pre-Christian and early Christian centuries these sites were commonly identified—rightly or wrongly—with various Stations of the Exodus.

I still believe that Kibroth Hattaavah is to be sought nearly 100 km to the east of Serabit el-Khadim, and not 20 km to the south, in the vicinity of Gebel Mokattab.

To be continued ...

References

- Uvi Avner, Nabataeans in Southern Sinai, ARAM Periodical, Volume 27, Numbers 1 & 2, pp 397-429, ARAM Society for Syro-Mesopotamian Studies, Peeters Online Journals (2016)

- Itzhaq Beit-Arieh, Archaeology of Sinai: The Ophir Expedition, Monograph Series, Number 21, Emery and Claire Yass Publications in Archaeology, Institute of Archaeology, Tel Aviv University, Tel Aviv (2003)

- Robert Clayton, A Journal from Grand Cairo to Mount Sinai, and Back Again., 2nd Edition, W Bowyer, London (1753)

- Charles Forster, The One Primeval Language, Second Edition, Part 1, Richard Bentley, London (1852)

- Louis Ginzberg, The Legends of the Jews, Volume 3, Translated from the German by Paul Radin, The Jewish Publication Society of America, Philadelphia (1911)

- James K Hoffmeier, Ancient Israel in Sinai: The Evidence for the Authenticity of the Wilderness Tradition, Oxford University Press, Oxford (2005)

- Carsten Niebuhr, Voyage en Arabie & en d’autres pays circonvoisins, Translated from the German Reisebeschreibung nach Arabien und andern umliegender Ländern, Volume 1, S J Baalde, Amsterdam (1776)

- James Orr (General Editor), The International Standard Bible Encyclopedia, Volume 4, The Howard-Severance Company, Chicago (1915)

- Edward Henry Palmer, Desert of the Exodus: Journeys on Foot in the Wilderness of the Forty Years’ Wanderings, Deighton, Bell, and Co, Cambridge (1871)

- Isidore Singer (managing editor), The Jewish Encyclopedia, Volume 1, Funk & Wagnalls Co, New York (1901)

- Robert Walter Stewart, The Tent and the Khan: A Journey to Sinai and Palestine, William Oliphant and Sons, Edinburgh (1857)

- James Strong, Hebrew and Chaldee Dictionary, in The Exhaustive Concordance of the Bible, Eaton & Mains, New York (1890)

Image Credits

- The Western Sinai Peninsula: University of Texas Libraries, Perry-Castañeda Library Map Collection, Aqaba, Suez, D Survey, Great Britain War Office and Air Ministry (1960), Public Domain

- From Serabit el-Khadim towards ’Ain el-Hudhera: Google Maps, Map Data © 2020 Mapa GISrael, ORION-ME, Fair Use

- Map Symbol Plane Clip Art: Openclipart, Public Domain

- Erweis el Ebeirig and ’Ain el-Hudhera: Emil G Kraeling, Egypt and Lands of the Exodus, Rand McNally Bible Atlas, Rand McNally & Company, New York (1956, 1962, 1966), Fair Use

- Standing Stones at Serabit el-Khadim: © 2005-2016 Zoltan Matrahazi, Fair Use

This post was shared in the Curation Collective Discord community for curators, and upvoted and resteemed by the @c-squared community account after manual review.

@c-squared runs a community witness. Please consider using one of your witness votes on us here

Downvoting a post can decrease pending rewards and make it less visible. Common reasons:

Submit