How much time elapsed between the Conquest of Canaan and the establishment of the Divided Monarchy? If the Short Chronology implies that these two events occurred one after the other without a break, then we are left with no time for a Period of Judges or a United Monarchy. If, on the other hand, a considerable period of time elapsed between these events, then we must find the archaeology that fills this gap.

In one of the first articles of this series we tried to establish two secure dates between which the history of Israel from the Exodus to the Fall of Jerusalem could be placed: an Alpha and an Omega of Israelite history, if you like. In this article we will revisit the arguments that led us to those dates and see if they need to be revised in the light of our subsequent research.

In Search of the Exodus

The Exodus was the defining event in the history of the ancient Israelites. But did it actually take place?

Most histories of ancient Israel no longer consider information about the Egyptian sojourn, the exodus, and the wilderness wanderings recoverable or even relevant to Israel’s emergence ... Most important is the fact that no clear extrabiblical evidence exists for any aspect of the Egyptian sojourn, exodus, or wilderness wanderings. This lack of evidence, combined with the fact that most scholars believe the stories about these events to have been written centuries after the apparent setting of the stories, leads historians to a choice ... admit that, by normal, critical, historical means, these events cannot be placed in a specific time and correlated with other known history, or claim that the stories are believable historically on the basis of inference, potential connections, and general plausibility. ―Moore & Kelle 81

Even today in the 21st century there are still a few mainstream scholars who argue for an historical Exodus―the British Egyptologist Kenneth Kitchen is perhaps the best known―but they represent an ever-dwindling minority. These scholars have had to greatly reduce the scale of the event in order to explain why there is so little archaeological evidence in favour of it:

The Mediterranean littoral was heavily used by the Egyptian army during the New Kingdom, and the remainder of Sinai shows little evidence of occupation for virtually the entire second millennium BCE, from the beginning of the Middle Bronze Age to the beginning of the Iron Age or even later. Even the site currently identified with Kadesh-barnea provides no evidence of habitation prior to the establishment of the Israelite monarchy. ―Coogan 77

The archaeologists may not have found any evidence of the Exodus in the 2nd millennium, but were they simply looking in the wrong time frame? If an historical Exodus took place, its only plausible location in the timeline of the Short Chronology is sometime in the 1st millennium.

An alternative approach to the problem is to find an historical analogue for the Exodus in the history of Egypt, an event that may represent the kernel of truth in the Biblical myth. There is such an event, one so suggestive of the Exodus that not even skeptics can afford to ignore it:

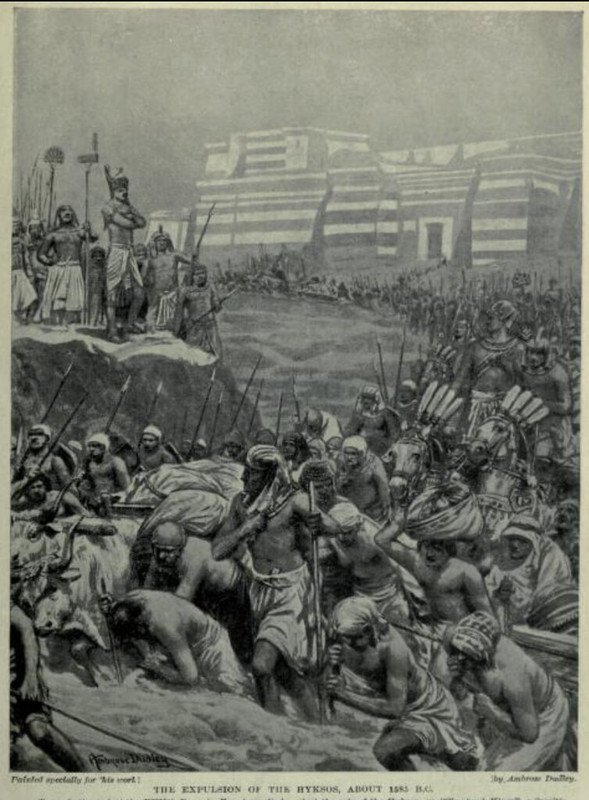

Counterparts, general or specific, to the Israelite “Exodus from Egypt” are more difficult to establish ... The closest historical parallel to the Israelite departure from Egypt, and the only known comparatively large-scale exodus of Asiatics from Egypt, is the expulsion of the Hyksos that marked the end of the Second Intermediate Period and the beginning of the New Kingdom. In fact, the Hyksos provide the only historical parallel that incorporates all three major elements of the biblical Exodus narrative―descent, sojourn, and departure ... ―Coogan 76

The expulsion of the Hyksos sounds so like the Biblical Exodus that it was actually identified with the Exodus almost two thousand years ago by the Jewish historian Josephus. Citing the native Egyptian priest and historian Manetho, Josephus writes:

Tutimaeus: In his reign, for what cause I know not, a blast of God smote us; and unexpectedly, from the regions of the East, invaders of obscure race marched in confidence of victory against our land. By main force they easily seized it without striking a blow; and having overpowered the rulers of the land, they then burned our cities ruthlessly, razed to the ground the temples of the gods, and treated all the natives with a cruel hostility, massacring some and leading into slavery the wives and children of others ... Their race as a whole was called Hyksos, that is king-shepherds ... These kings dominated Egypt, according to Manetho, for 511 years. Thereafter, he says, there came a revolt of the kings of the Thebaid and the rest of Egypt against the Shepherds, and a fierce and prolonged war broke out between them. By a king whose name was Misphragmuthosis, the Shepherds, he says, were defeated, driven out of all the rest of Egypt, and confined in a region ... by name Auaris. According to Manetho, the Shepherds enclosed this whole area with a high, strong wall, in order to safeguard all their possessions and spoils. Thummosis, the son of Misphragmuthosis (he continues), attempted by siege to force them to surrender, blockading the fortress with an army of 480,000 men. Finally, giving up the siege in despair, he concluded a treaty by which they should all depart from Egypt and go unmolested where they pleased. On these terms the Shepherds, with their possessions and households complete, no fewer than 240,000 persons, left Egypt and journeyed over the desert into Syria. There, dreading the power of the Assyrians who were at that time masters of Asia, they built in the land now called Judaea a city large enough to hold all those thousands of people, and gave it the name of Jerusalem. ―Josephus, Against Apion 1:75–90)

Josephus’s source for this history was Manetho’s Aegyptiaca, a Greek history of Egypt written by the Egyptian priest for the Macedonian Ptolemies. In the first article in this series, Making History, I mentioned some of the shortcomings of this work. Manetho is suspected of magnifying the history of his country beyond the bounds of credibility. When, however, he describes Egypt’s humiliating occupation by a race of cruel foreigners, there are fewer grounds for skepticism. Only fragments of the Aegyptiaca survive, and sources often differ from one another. It is to Josephus that we owe the existence of the preceding passage.

There are, however, more ancient Egyptian records of the subjugation of the country by the Hyksos and their subsequent expulsion. The celebrated Egyptologist James Henry Breasted briefly summarizes this period of Egyptian history in these words:

The fall of the Twelfth Dynasty in 1788 B. C. was followed by a second period of disorganization and obscurity, as the feudatories struggled for the crown. Now and then an aggressive and able ruler gained the ascendency for a brief reign, and under one of these the subjugation of Upper Nubia was carried forward to a point above the third cataract; but his conquest perished with him. After possibly a century of such internal conflict, the country was entered and appropriated by a line of rulers from Asia, who had seemingly already gained a wide dominion there. These foreign usurpers, now known as the Hyksos, after Manetho’s designation of them, maintained themselves for perhaps a century. Their residence was at Avaris in the eastern Delta, and at least during the later part of their supremacy, the Egyptian nobles of the South succeeded in gaining more or less independence. Finally the head of a Theban family boldly proclaimed himself king, and in the course of some years these Theban princes succeeded in expelling the Hyksos from the country, and driving them back from the Asiatic frontier into Syria. ―Breasted 1905:17

In his Ancient Records of Egypt, Breasted draws attention to an inscription from the time of Ahmose I, the founder of the 18th dynasty and the Pharaoh now credited with liberating Egypt from the Hyksos. The inscription, on the wall of a cliff-tomb at El Kab, is the biography of a naval officer who served under three Pharaohs, including Ahmose, whose name he shared:

After an introduction and a few words about his youth and parentage, Ahmose plunges directly into his first campaign, with an account of a siege of the city of Hatwaret (ḥ·t-w‘r·t). This can be no other than the city called Avaris by Manetho (Josephus, Contra Apion, I, 14), where, according to him, the Hyksos make their last stand in Egypt ... The siege, which must have lasted many years, was interrupted by the rebellion of some disaffected noble in Upper Egypt; but the city was finally captured, and the Hyksos, fleeing into Asia, were pursued to the city of Sharuhen (Josh. 19:6). Here they were besieged for six years by Ahmose I, and this stronghold was also captured. ―Breasted 1906:2:4–5

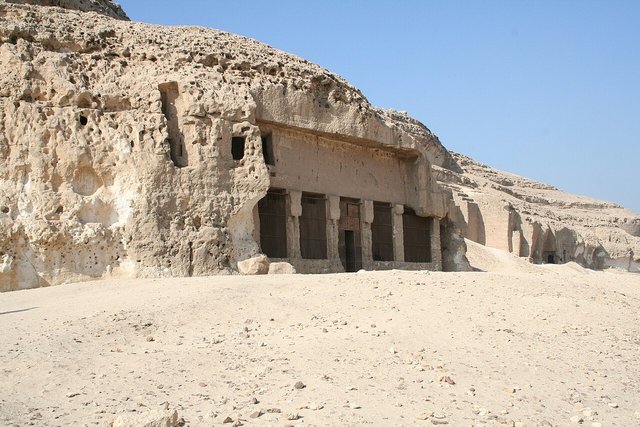

Breasted also draws attention to an inscription which Ahmose I’s great-granddaughter Hatshepsut left in the temple of Pakhet at Speos Artemidos, about 28 km south of Al Minya:

In this remarkable document the energetic queen has left a record of her systematic restorations in the temples which had been desolated by the barbarities of the Hyksos, and had remained so down to her reign ... Its references to the Hyksos coincide remarkably with the account of their treatment of the temples as recorded by Manetho. The Hyksos are called “Asiatics” (’mw), and their city is “Avaris (ḥ·t-w‘r·t) of the Northland .” ―Breasted 1906:2:122

In the mainstream chronology, the expulsion of the Hyksos is now dated to about 1550 BCE, which is considered too early for the Exodus. So the archaeologists have been searching for the Exodus in a later period of Egyptian history, such as the 19th dynasty (which they place around 1200 BCE). But what does the Short Chronology have to say about the Hyksos?

Gunnar Heinsohn and the Hyksos

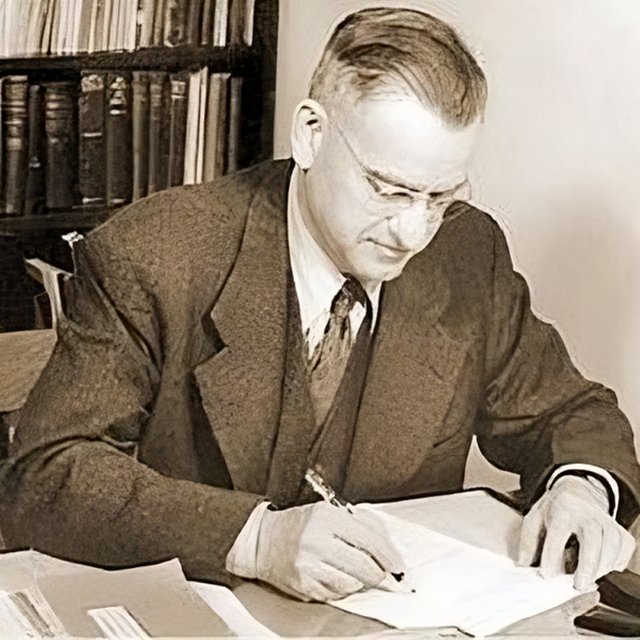

Gunnar Heinsohn, Professor Emeritus at the University of Bremen, is one of the pioneers of the Short Chronology. An economist by education, in the 1980s he began to study ancient history and quickly came to the conclusion that the chronology taught in textbooks was at odds with the stratigraphic record. Heinsohn believed that civilization arose in the Near East around 1000 BCE. One of Heinsohn’s most brilliant insights was the concept of the triplication of ancient history. Here is how his disciple, Emmet Sweeney, describes this idea:

The chronology of the ancient Near East was put together using three quite separate dating blueprints, each a replica of the other, which produced in the end an actual triplication of ancient history. There was the history of the region known to the classical authors, covering the first millennium BC, which was in fact the true history of the region. A duplicate history, placed in the second millennium, was then supplied by applying material from Egypt, and another phantom history, this time placed in the third millennium, was supplied by cross-referencing with Mesopotamian material. Thus the Akkadians of the third millennium are in fact stratigraphically contemporary with (and identical to) the Hyksos of the second millennium; and both are one and the same as the Assyrians of the first millennium BC. ―Sweeney 76

Heinsohn, then, concluded that the Akkadians, the Imperial Assyrians and the Hyksos were one and the same people. The Akkadian Empire of supposedly 2300–2100 BCE, the Old Assyrian Empire of 2000–1400 BCE and the Hyksos Kingdom of 1650–1550 BCE were actually the same empire, which belonged to a period of history much closer to the present time―roughly 900–700 BCE in the model of the Short Chronology that I favour.

Josephus, citing Manetho, clearly distinguishes the Hyksos from the Assyrians. But it is worthy of note that he synchronizes their expulsion from Egypt with the height of Assyrian power in Asia:

Finally [the Hyksos] made one of their number, named Salitis, king. He resided at Memphis, exacted tribute from Upper and Lower Egypt, and left garrisons in the places most suited for defence. In particular he secured his eastern flank, as he foresaw that the Assyrians, as their power increased in future, would covet and attack his realm ... [The Hyksos] left Egypt and traversed the desert to Syria. Then, terrified by the might of the Assyrians, who at that time were masters of Asia, they built a city in the country now called Judaea, capable of accommodating their vast company, and gave it the name of Jerusalem. ―Josephus 1:77 ... 89–90

Josephus clearly believed that the Hyksos were the ancient Israelites. That is not what the Short Chronologists believe. According to Heinsohn and Sweeney the Hyksos were Assyrians : the Israelites and other Semitic peoples were their clients and allies. When the Assyrians were expelled from Egypt, their allies were also obliged to leave, so the Biblical Exodus was merely one chapter in the history of the Hyksos expulsion. This is actually in agreement with the Bible, which explicitly states that the Israelites were accompanied on the Exodus by a mixed multitude of non-Israelites:

And the children of Israel journeyed from Rameses to Succoth, about six hundred thousand on foot that were men, beside children. And a mixed multitude went up also with them; and flocks, and herds, even very much cattle. ―Exodus 12:37–38

When did all this take place according to those who espouse the Short Chronology?

Dating the Exodus

While Sweeney agrees with Heinsohn’s Hyksos-Assyrian equation, he does not believe that the Biblical Exodus occurred at the time of the Hyksos expulsion. Sweeney places the Exodus around 850 BCE, half a century before the Hyksos invaded Egypt. On this point I disagree with him. As a working hypothesis, I accept the synchronism of the Exodus and the expulsion of the Hyksos. The latter is the only event in Egyptian history that can account for something as epochal as the Exodus. In this regard, I am in agreement with another prominent proponent of the Short Chronology, Charles Ginenthal. Although Ginenthal is an avowed disciple of Immanuel Velikovsky, he has always been prepared to revise Velikovsky’s theories in the light of new evidence:

Velikovsky in Worlds in Collision maintained that the Earth had undergone two periods of celestial catastrophes. The first two events occurred around 1500–1400 B.C. ... The second period of catastrophes was lower in its destructiveness, and these occurred around 800 to 700 B.C. ... One of Velikovsky’s major themes was that of the Venus near-collision with Earth around 1500–1400 B.C. in which the Hebrew slaves in Egypt left that land after a series of catastrophes. Since the short chronology only allows high civilization to arise about 1200–1100 B.C. [Heinsohn now favours a date closer to 1000 BCE], Velikovsky’s chronology cannot be historically or scientifically correct. Heinsohn, on the other hand, sets the Exodus in Hyksos/Akkadian/Assyrian times in the 8th century B.C. with the Hebrew host as allies to the Hyksos. Thus, the catastrophe, related not only to the ones described above ranging across the ancient world, which brought down a great number of cities, towns, and villages via earthquakes, floods, and fires, had to have also been the same one related in the chronicle of the biblical Exodus. ―Ginenthal 2010:440 ... 440 ... 505

Velikovsky anchored the second series of catastrophes between 776 and 687 BCE. In the Short Chronology, this is roughly where we must place the Exodus―at least as a working hypothesis. But can we do any better than a rough estimate?

Pinning Down the Exodus

According to the Book of Exodus, the Israelites were guided on their way through the wilderness by a pillar of cloud during the day and by a pillar of fire during the night:

And the Lord went before them by day in a pillar of a cloud, to lead them the way; and by night in a pillar of fire, to give them light; to go by day and night: He took not away the pillar of the cloud by day, nor the pillar of fire by night, from before the people. ―Exodus 13:21–22

Charles Ginenthal is not the first person to suggest that these bright pillars might have been a comet:

... the people crossing the Sinai would have arrived there around June, after three-months—three new moon periods—which brings us to the pillar of light in the sky by day and of fire by night which was probably a comet, Halley’s Comet, another somewhat common event dated to 763 B.C. Duncan Steel dates the apparition of Halley’s Comet tentatively to August of 763 B.C. ―Ginenthal 2010:542

Ginenthal cites Marking Time by the British astrophysicist Duncan Steel. Steel discusses an eclipse of the Sun that is mentioned several times in the Bible, including Job 9:6–7. Following the conventional chronology, Steel identifies this event with a solar eclipse that is tentatively dated to 15 June 763 BCE. In Volume 2 of his Pillars of the Past Ginenthal discusses this eclipse at considerable length (Ginenthal 2008:164–185). Steel also wrote about this event in his earlier work Eclipse:

Various events around 760 B.C., culminating in a major earthquake that damaged Solomon’s Temple in Jerusalem and caused a huge destructive wave in the Sea of Galilee, clearly had a considerable effect upon the people of Judea. The fact that the rumble was felt over 800 miles away allows us to estimate that the tremble was about magnitude 7.3 on the Richter scale. In the Bible there are eight separate allusions to a solar eclipse around that time, which may be identified as June 15, 763 B.C. We are told the eclipse was followed closely by a bright comet. If this was Halley’s Comet (we cannot be sure due to the sparsity of the information) then we know from a backwards extrapolation of its orbit that the comet indeed would have been visible in August of 763 B.C., five centuries before the earliest definite observation cited above. ―Steel 2001:20

Steel, then, has suggested that this bright comet was none other than Comet Halley, the most famous of all comets. Steel believes that the earthquake, eclipse and cometary apparition all happened more than half a millennium after the Exodus, but Ginenthal is happy to draw the conclusion that the famous pillar of cloud by day and of fire by night was Halley’s Comet. It is a stretch and a rather thin thread from which to hang our chronology, but 763 is close to where I would like to place the Exodus. The earliest confirmed sighting of Comet Halley occurred in 240 BCE. With a period of approximately 75 years, an earlier apparition would have occurred around 763. But the periodicities of short-period comets are subject to variations due to gravitational perturbations and outgassing, so retrocalculations of their earlier apparitions must be subject to considerable uncertainty.

Nevertheless, let us tentatively anchor the Biblical Exodus (and the Expulsion of the Hyksos) to the year 763 BCE. This is our Alpha.

The Fall of Jerusalem

After the Exodus the defining events in the history of ancient Israel are surely the destruction of the Temple of Solomon and the Babylonian Captivity. This twin tragedy marked the end of the Kingdom of Judah, which makes it the obvious choice for our Omega. The Kingdom of Israel had ceased to exist more than a century earlier.

In the conventional chronology there is still no consensus on the precise date of this epochal event, though there is now broad agreement that it occurred in either 587 or 586 BCE. William F Albright favoured the earlier year, but Edwin R Thiele, Kenneth Kitchen and Gershon Galil all favoured the later date. Earlier scholars―eg James Ussher and Isaac Newton―dated this event to 588 BCE.

There is also a lack of consensus among the proponents of the Short Chronology. Emmet J Sweeney places the Fall of Jerusalem in the reign of the Persian Emperor Artaxerxes III, whom he identifies with the Biblical King of Babylon Nebuchadnezzar. Lynn E Rose and Charles Ginenthal, however, adopted a much more radical realignment of the timescale and placed the sack of Jerusalem in the year 312 BCE. This date requires that Nebuchadnezzar―by repute the greatest king in the history of Babylon―be nothing more than a provincial governor, a vassal of the ruling Macedonian Seleucids. I find this too large a pill to swallow. Sweeney’s reconstruction makes more sense to me―though Rose always claimed that he had very good astronomical records to support his timeline.

Sweeney’s identification of Artaxerxes III and Nebuchadnezzar II is supported by the Book of Judith:

Before moving on, it should be noted that the Book of Judith, hitherto one of the most enigmatic of traditional Hebrew texts, takes on an altogether new significance in the light of the reconstruction proposed here. Judith is said to have lived during the time of a Nebuchadrezzar who is described as “King of Assyria.” No king of Assyria of this name is said to be known. Yet this Mesopotamian monarch is involved in events strikingly similar to those of his namesake who deported the people of Judah. He is said to have summoned the peoples of the west, including the Egyptians, to assist him in a war against the Medes. When this summons is ignored, he sets out, in his eighteenth year, to punish the traitors, who include Egyptians and Jews (Judith 2). This march to the west recalls the action taken by the other Nebuchadrezzar in the same region in his sixteenth year. Could it be that the Book of Judith provides an account of an otherwise obscure episode of the war against Nebuchadrezzar in the time of [King Zedekiah]―the war which we have identified as Arta Xerxes III’s second campaign against Egypt? One striking detail in the Book of Judith seems to confirm this. We are told that Nebuchadrezzar’s general Holofernes, whom Judith assassinates, had a eunuch named Bagoas (Judith 12:11). Yet Bagoas was the name of the trusted eunuch who assassinated Arta Xerxes III. Even more to the point, Arta Xerxes III also had a general named Holofernes. According to Diodorus [Bibliotheca historica 31:19:2], this Holofernes was a Cappadocian who accompanied Arta Xerxes III in his campaign against the Egyptians. Strange then that the Book of Judith would name as servants of Nebuchadrezzar two characters with names identical to two servants of Arta Xerxes III! ―Sweeney 153–154. I have emended Sweeney’s King Hezekiah to King Zedekiah, to whom he is clearly referring.

In a series of bullet points, Sweeney summarizes the similarities between these two rulers, who are alleged to have been separated in time by more than two centuries (Sweeney 153):

Both kings were rulers of Babylon, who clashed with Egypt.

Arta Xerxes III’s first war against Egypt occurred in his eighth year, and ended in failure. Nebuchadrezzar’s first war against Egypt took place in his eighth or ninth year and apparently ended in failure.

The Egyptian enemy of Arta Xerxes III was known as Nectanebo II. The Egyptian enemy of Nebuchadrezzar was known as Necho II.

Arta Xerxes III’s second campaign against Egypt occurred in his sixteenth year and was successful. Nebuchadrezzar’s second campaign against Egypt occurred in his sixteenth or seventeenth year and resulted in the conquest of the Nile Kingdom.

Arta Xerxes III’s Egyptian enemy Nectanebo II used Greek mercenaries against the Great King. Nebuchadrezzar’s Egyptian enemy Necho II used Greek mercenaries against him.

Artaxerxes III reigned for twenty years from 358 to 338 BCE, a figure which Sweeney has some difficulty squaring with the forty-three years usually ascribed to Nebuchadnezzar. His second, successful campaign against Egypt took place in 343 BCE. Is this the true date of the Fall of Jerusalem?

Seder Olam Rabbah

In an earlier article in this series I examined the rabbinical chronological treatise known as the Seder Olam Rabbah. Dates in this work are often at variance with the conventional dates in our history books. The destruction of the Temple of Solomon is set in the year 3338 AM (Anno Mundi), when the Babylonian Captivity began:

The Jews were in captivity in Babylon for 52 years before being freed by Cyrus. Cyrus continued his reign after he conquered Babylon for only three years. Then Ahasuerus ruled for 14 years, followed by Darius. In the second year of the reign of Darius, the Temple was rebuilt. ―Johnson 4529–4536

The Temple was finished in only four years, as it is written: “And this house was finished on the third day of the month Adar, which was in the sixth year of the reign of Darius the king.” Ezra 6: 15 ―Johnson 4569–4574

Rabbi Yose said: the Persian Empire continued to exist for [34] years after the new Temple was completed. The Grecian Empire ruled after Persia for 180 years. After the fall of the Grecian Empire, the Hasmonean Dynasty, starting under Judas Maccabee, ruled Israel for 103 years. Then under Roman rule, the kingdom of Herod existed for 103 years before the Temple was destroyed. ―Johnson 4725–4732

(Johnson’s translation has 24 years for the Persian period after the completion of the Second Temple, but every other source I have consulted translates this passage as 34 years.)

Rabbi Yose’s timeline, then, for the period between the destruction of the First Temple and the destruction of the Second Temple is as follows:

| Years | Period or Event |

|---|---|

| - | Nebuchadnezzar destroys the Temple of Solomon in 3338 AM |

| 52 | Babylonian Captivity |

| 3 | Cyrus |

| 14 | Ahasuerus (Xerxes) |

| 1 | Darius’ 1st year |

| - | In Darius’ 2nd year construction of the Second Temple begins |

| 4 | Construction of the Second Temple |

| - | In Darius 6th the construction of the Second Temple is completed |

| 34 | Persian rule after the Second Temple is built |

| 180 | Grecian rule |

| 103 | Hasmonean rule |

| 103 | Herodian rule under the Romans |

| - | The Second Temple is destroyed |

Adding up, we see that 495 years elapsed between the destruction of the First Temple and the destruction of the Second Temple. Almost everyone―conventional historians and Short Chronologists alike―places the latter event in 70 CE. The destruction of the Temple of Solomon, then, must be dated to the year 425 BCE. This is more than one-and-a-half centuries later than the conventional chronology.

In another passage of the Seder Olam Rabbah, Rabbi Yose is again quoted:

Rabbi Yose also said: It was 70 years between the destruction of the First Temple to the dedication of the Second Temple. Add to that [420] years and we come to the 490 years of the prophecy which ended at the destruction of the Second Temple. ―Johnson 4264–4270

This places the destruction of Solomon’s Temple in the year 420 BCE. Other rabbinical sources (eg the Babylonian Talmud) lead to slightly different dates―423, 422, 421 BCE―but they are all in this general time frame. Whichever precise year we accept will be more than 160 years later than the conventional date, and much closer to Sweeney’s date.

Ken Johnson, the translator of the Seder Olam Rabbah comments on the above passage:

It has already been stated and verified that the period of the Persian rule covered 210 years; but here Yose is trying to make it 24 years [recte 34]. This difference is the famous 168 years that are missing from the Jewish calendar. This is why AD 2007 is 5766 AM instead of 5930 or 5934 AM. ―Johnson 5702–5704)

210 minus 24 equals 186. Perhaps Johnson’s 168 years is a typo. But various figures are given for the number of missing years in the Jewish calendar: it all depends on which source you consult.

But what about 425 BCE? Could this be the true date of the destruction of Solomon’s Temple? It is certainly worth bearing in mind, but I prefer Sweeney’s 343 BCE as a working model. We have already settled on 763 BCE as a working date for the Exodus, and the rabbinical date would only leave us 338 years in which to fit all the intervening history. Sweeney’s 420 years is much more generous in this respect.

Let us, therefore, take 343 BCE as the date of the Fall of Jerusalem and the beginning of the Babylonian Captivity.

Timeline of the Kingdom of Judah

How long did the Kingdom of Judah last? This, too, we considered in an earlier article. We saw that several supporters of the Short Chronology accepted the relative chronology of Edwin R Thiele’s The Mysterious Numbers of the Hebrew Kings but not Thiele’s absolute dates. Lynn E Rose, for example, wrote the following in an appendix to Volume 4 of Charles Ginenthal’s Pillars of the Past:

With some caveats, I accept virtually all of Edwin Thiele’s work, especially the durations that he recognizes. As will be explained later, however, I accept Thiele as a relative chronology only. In order to make it absolute, I have to move his whole chronology forward in time by 274 years. ―Ginenthal 623–624

I agree very strongly with Thiele’s overall analysis and reconstruction of Biblical chronology. He deals rather briefly with the United Kingdom of Saul, David, and Solomon, and then in great detail with the Divided Monarchy of Israel and Judah. His chronology seems to me to be brilliant. So far, I have little reason to doubt that it is correct both as a relative or sequential chronology, and also in terms of durations ...

The major respect in which I disagree with Thiele is that his entire chronology fails as an absolute chronology. He tries to make it absolute by linking Biblical events to Assyro-Babylonian events. He takes it as established that Assyro-Babylonian chronology is both absolute and correct ... ―Ginenthal 644-645

Rose & Ginenthal wished to translate Thiele’s chronology forward in time by 274 years, placing the Fall of Jerusalem and the Destruction of the Second Temple in the year 312 BCE. But if we accept Sweeney’s estimate of 343 BCE for these events, then we need only translate Thiele’s chronology by 243 years.

What is more relevant to our present discussion, however, is the duration Thiele assigns to the Kingdom of Judah: 345 years, with the first year of Rehoboam occurring in 931 BCE and the Fall of Jerusalem in 586 BCE. If we accept this timespan and Sweeney’s date of 343 BCE for the Fall of Jerusalem, then we must place the first year of Rehoboam’s reign in the year 688 BCE. Let us take this as our working model.

From the Exodus to the Divided Monarchy

How much time elapsed between the Exodus and the start of the Divided Monarchy? That is the next question we need to answer. Simple arithmetic gives the following answer, using the figures that we have tentatively accepted:

Our Estimate for the Date of the Exodus: 763 BCE

Our Estimate for the Foundation of the Kingdoms of Israel & Judah: 688 BCE

Elapsed Time between the Exodus and the Divided Monarchy: 75 years.

Is this figure consistent with the Short Chronology of Egypt? According to our thesis, the Exodus occurred in the very year that opened the Eighteenth Dynasty. Can we find a link between the Egyptian chronology and the rise of the Divided Monarchy? I believe we can.

In I Kings 14 we read:

And Rehoboam the son of Solomon reigned in Judah. Rehoboam was forty and one years old when he began to reign, and he reigned seventeen years in Jerusalem, the city which the Lord did choose out of all the tribes of Israel, to put his name there ... And it came to pass in the fifth year of king Rehoboam, that Shishak king of Egypt came up against Jerusalem: And he took away the treasures of the house of the Lord, and the treasures of the king’s house; he even took away all: and he took away all the shields of gold which Solomon had made. ―I Kings 14:21–26 : II Chronicles 12

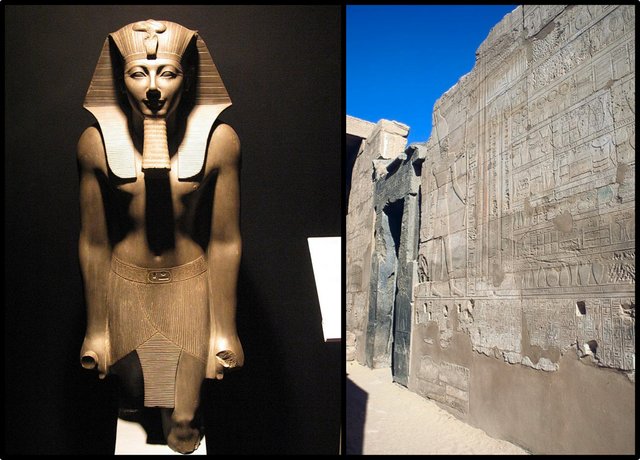

In the first volume of Ages in Chaos, which was published in 1952, Immanuel Velikovsky identified Shishak with Thutmose III, the sixth Pharaoh of the 18th Dynasty. Many of the proponents of the Short Chronology accept this identification, as do I.

... Egyptian sources say that after the death of Hatshepsut, her ambitious young nephew Thutmose III launched a series of devastating invasions of Palestine and Syria, scoring some of the greatest military triumphs in Egypt’s history. In his first campaign, directed against Palestine, he plundered the treasures of the great temple in the city of Kadesh, which is named as the region’s most important center. These treasures Thutmose displayed on the walls of his temple at Karnak. Kadesh, as Velikovsky demonstrated, can be little other than Jerusalem, the Holy (Kadesh) mountain, by which name (Al Kuds) the city is still known in modern Arabic. ―Sweeney 77

Velikovsky never explained why Thutmose was referred to in the Biblical texts as Shishak. Emmet Sweeney, however, has offered the following explanation:

One of Thutmose’s numerous titles (his Golden Horus name) was Djeser-kau, which was probably pronounced something like Shesy-ka, very close indeed to the biblical Shishak. ―Sweeney 77

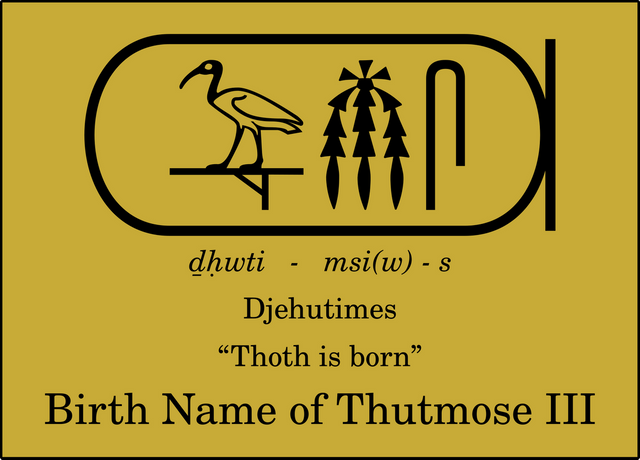

I prefer to see sh as the Biblical transliteration of certain Egyptian sounds, such as ḏḥ and tj, which became θ in Greek. The Birth Name of Thutmose is Djehutimes, which means “Thoth Is Born”. When written in Egyptian hieroglyphs, the first element in this name is the sign for the god Thoth―the ibis, or ḏḥwtj in Ancient Egyptian. If Egyptian ḏḥ and tj both gave the Hebrew sh, then Thoth would have given the consonantal sh-sh. A similar transliteration explains why Hatshepsut, the Queen of Thebes, is known in the Bible as the Queen of Sheba. The etymology of Thebes is uncertain, but the Greek form is Θῆβαι [Thēbai], so a Hebrew form beginning with Sh- would be expected.

As David Rohl―who identified Shishak with Ramesses II, believing the original form of the name was Sysa―once pointed out, it would be natural for Biblical scholars to use the consonantal skeleton sh-sh to construct a Hebrew name that characterized the Pharaoh:

The last round of the ‛name game’ is to explain the final ‛k’ (Heb. qoph) in the name Shishak which is not present in the original Egyptian. The best explanation is to be found in the way that the biblical redactor often makes a play on words, particularly when dealing with foreign names. This is usually done to pour scorn on those who do not follow in the path of Yahweh. For instance, the original writing of the famous name Jezebel (borne by the Phoenician wife of King Ahab) is attested on a contemporary ninth century scarab as Yzebel, meaning ‛[Baal] is prince’. However, the redactor turns this into Ayzebel which means “Where is the piece of dung (i.e. Baal)’. Did the redactor do the same with the Egyptian name Sysa? If so, then he chose a very appropriate pun because the name Shishak may be derived from the Hebrew name Shashak, meaning ‛assaulter’ or ‛the one who crushes [under foot or under wheel]’―a most descriptive synonym for Ramesses the Great who ‛crushes the rebels on top of the hill’. ―Rohl 162–163

And also an appropriate name also for Thutmose III, who is widely acknowledged to have been the greatest conqueror Egypt ever produced.

The identification of Thutmose III and Shishak is, of course, rejected by most Egyptologists, and also by some revisionists. Velikovsky’s and Sweeney’s arguments in favour of this identification will be examined in detail by us in a later article.

The following table lists the first six Pharaohs of the 18th Dynasty with the lengths of their reigns (excluding co-regencies)

| Pharaoh | Length of Reign (Years:Months) |

|---|---|

| Ahmose I | 25:4 |

| Amenhotep I | 20:7 |

| Thutmose I | 12:9 |

| Thutmose II | 3? |

| Hatshepsut | 21:9 |

| Thutmose III | 32 |

Manetho assigns a reign of 13 years to Thutmose II, but many Egyptologists believe that the correct figure is 3. If we accept these figures, and place Ahmose’s first year in 763 BCE, then Thutmose III’s first campaign would have taken place around 679 BCE. Compare this with our earlier estimate for the first year of Rehoboam’s reign: 688 BCE. If this is correct, Rehoboam’s fifth year, when Shishak invaded, would have been 684 BCE. Considering that 763 BCE is a tentative date, I would regard this as a resounding endorsement of the Short Chronology. Perhaps we should adjust the first year of the 18th Dynasty to 768 BCE.

Putting It All Together

As a working model, then, I shall adopt the following amended timeline:

768 BCE: The Exodus : The Expulsion of the Hyksos : Year 1 of Ahmose I and the 18th Dynasty

688 BCE: The Start of the Divided Monarchy : Year 1 of Jeroboam of Israel : Year 1 of Rehoboam of Judah

684 BCE: Thutmose III’s First Campaign

343 BCE: The Fall of Jerusalem : The Beginning of the Babylonian Captivity

There were, therefore, 80 years between the Exodus and the rise of the two Kingdoms of Israel and Judah. If the Wandering in the Desert and the Conquest of Canaan only occupied a couple of years or so―as I have previously argued―then we are left with over 70 years to fill before the start of the Divided Monarchy.

What happened during these 70-odd years? Was there a United Kingdom of Israel under a short-lived Saulide Dynasty? Is there any archaeological evidence to support such a state? These are the questions we will be trying to answer in the next article.

And that’s a good place to stop.

References

- James Henry Breasted, A History of Egypt: From the Earliest Times to the Persian Conquest, Charles Scribner’s Sons, New York (1905)

- James Henry Breasted, Ancient Records of Egypt, Volumes 1–5, The University of Chicago Press, Chicago (1906)

- Michael D Coogan (editor), The Oxford History of the Biblical World, Oxford University Press, Inc, New York (2001)

- Megan Bishop Moore, Brad E Kelle, Biblical History and Israel’s Past: The Changing Study of the Bible and History, William B Eerdmans Publishing Company, Grand Rapids, Michigan (2011)

- Emmet J Sweeney, The Ramessides, Medes and Persians, Ages in Alignment, Volume 4, Algora Publishing, New York (2007)

- H St J Thackeray (editor, translator), Josephus: The Life, Against Apion, Loeb Classical Library, William Heinemann, London (1926)

- Charles Ginenthal, Mesopotamian, Anatolian, Mycenaean, Minoan, and Harappan Chronology, Pillars of the Past, Volume 2, Forest Hills, New York (2008)

- Charles Ginenthal, Egypt and Palestine, Pillars of the Past, Volume 3, Forest Hills, New York (2010)

- Ken Johnson, Ancient Seder Olam, Xulon Press, Camarillo, California (2006)

- Emmet John Sweeney, The Genesis of Israel and Egypt, Ages in Alignment, Volume 1, Algora Publishing, New York (2008)

- Immanuel Velikovsky, Worlds in Collision, Macmillan Publishers, New York (1950)

- Duncan Steel, Marking Time: The Epic Quest to Invent the Perfect Calendar, John Wiley & Sons, Incorporated, New York (2000)

- Duncan Steel, Eclipse: The Celestial Phenomenon that Changed the Course of History, The Joseph Henry Press, Washington, DC (2001)

Image Credits

- Jeroboam’s Sacrifice at Bethel: Gerbrand van den Eeckhout (artist), Hermitage Museum, Saint Petersburg, Public Domain

- The Expulsion of the Hyksos: Ambrose Dudley (artist), Walter Hutchinson, Hutchinson’s History of the Nations, Volume 1, Page 27, Hutchinson & Co, London (1915), Public Domain

- An Artist’s Impression of Avaris: © Fabricio Baessa (artist), Fair Use

- Hatshepsut’s Temple of Pakhet at Speos Artemidos: © Einsamer Schütze (photographer), Creative Commons License

- Gunnar Heinsohn: © Freud (photographer), Creative Commons License

- Charles Ginenthal: © Dwardu Cartona (photographer), Fair Use

- Joshua Passing the River Jordan with the Ark of the Covenant: Benjamin West (artist), Art Gallery of New South Wales, Public Domain

- Comet Halley in 1910: Giuseppe Calì (artist), Comet Halley over the Grand Harbour, Malta, Private Collection, Public Domain

- The Fall of Jerusalem: Anonymous Illustration, Fair Use

- Nebuchadnezzar II: The Tower of Babel Stele (Etemenanki, Babylon), The Schøyen Collection, Oslo, Robert Koldewey (photographer), Public Domain

- Artaxerxes III: Rock Relief at Persepolis, © Mardetanha (photographer), Creative Commons License

- Edwin R Thiele: Anonymous Photograph, Public Domain

- Thutmose III: Luxor Museum, Chipdawes (photographer), Public Domain

- His Annals at Karnak: The Annals of Thutmose III, Precinct of Amun-Re, Karnak Temple Complex, Karnak, Jon Bodsworth (photographer), Public Domain

- The Festival Hall of Thutmose III at Karnak: Precinct of Amun-Re, Karnak Temple Complex, Karnak, © Olaf Tausch (photographer), Creative Commons License

- Shishak Spoileth Jerusalem: II Chronicles 12:9: Hans Holbein the Younger (artist), Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam, Public Domain