September of 1918 was a fraught time in Philadelphia.

Day after day, newspaper headlines carried a grim mixture of battle updates from the Great War, seemingly endless lists war casualties, appeals for Liberty Loan bond donations, and cautious warnings about a new and dangerous strain of influenza that had begun to sweep army camps, killing with great speed and gruesomeness. Locally, however, another drama was playing out: a court trial that would have serious implications for the German-American community of Philadelphia and the limitation of free speech in wartime.

The Philadelphia Tageblatt was one of several German-language newspapers that catered to the large communities of German-speaking immigrants in the city. Founded in 1878, it “was instituted to fill the desire of the German Social Democrats here for a newspaper of their own.” [1] The news it provided generally followed along anti-monarchical and pacifist lines- which is why the editorials that appeared in the paper following the U.S. entry into the Great War in April of 1917 were increasingly critical in tone.

Conflicted Immigrants

Many German-Americans found it difficult to support a war that could claim the lives of their friends and family members. But in wartime this attitude was looked upon with suspicion, and immigrants frequently found themselves having to defend their American citizenship by denouncing their German heritage. This distrust of “the Huns” extended into the highest reaches of government. The Trading with the Enemy Act, the Espionage Act, and the Sedition Act- all targeting criticism of the government, especially by naturalized citizens “pour[ing] the poison of disloyalty into the very arteries of our national life”- passed into law shortly following the U.S. entry into the war. [2]

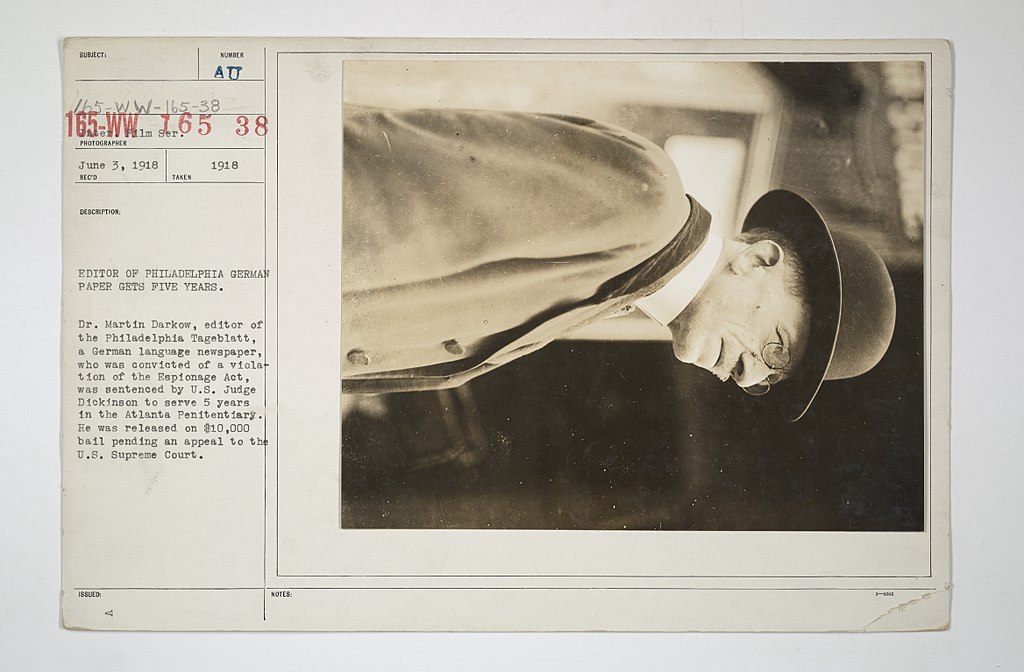

One of the defendants, Dr. Martin Darkow. "Enemy Activities" Card from the Records of the War Department held at National Archives and Records Administration.

One of the defendants, Dr. Martin Darkow. "Enemy Activities" Card from the Records of the War Department held at National Archives and Records Administration.It was under the enforcement of these Acts that federal agents raided the offices of the Philadelphia Tageblatt in 1917 and arrested a number of employees, five of which would later come to trial for sedition and violation of the Espionage Act. The defendants, all of German descent, were Peter Schaefer (publishing company president); Paul Vogel (treasurer); Louis Werner (chief editor); Dr. Martin Darkow (managing editor); and Herman Lemke (business manager). At trial, which began on September 23rd, the government sought “to show by these exhibits that the defendants with a common knowledge, intent and purpose, willfully substituted words and sentences in copied news dispatches so as to change their meaning and effect, and give encouragement to the friends of Germany and at the same time ignore, belittle, criticise and discredit any news favorable to the United States or any of the other countries making war against Germany.” [3]

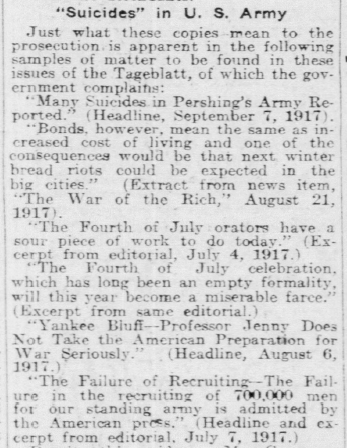

Among the evidence presented by the prosecution were a number of (translated) excerpts from the Tageblatt in 1917, including the following (From "Alien Foes Aided Tageblatt, Federal Evidence Discloses." Philadelphia Tribune, Sep. 25, 1918):

"Alien Enemies of this City"

Prosecutors attributed the paper’s increased subscribership to a dangerous public, claiming: “the Philadelphia Tageblatt was subscribed to and fostered by alien enemies of this city because of its rabid and defiant pro-German stand in the face of all laws and warnings to the contrary.” [4] Throughout the trial, the paper’s anti-war stance was continually framed as an anti-American one. “You write,” one of the prosecutors questioned frequent editorialist Louis Werner, “that peace will come from the masses and that the sooner we come to our sense the better. Do you think the influence of that statement friendly to the United States?” [5]

The defendants were all convicted on September 27, 1918, setting a precedent that struck a blow to the free speech protection of already-besieged German-Americans across the U.S. [6] This trial and other similar ones caused what a contemporary writer termed “the strategic retreat” of the German-American press into a tailspin of justifications for their very existence, often resulting in blatantly Americanist declamations. “A potent corrective for the negative attitude of certain papers,” the North American Review noted approvingly, “was the increasing pressure of an awakened patriotism among all Americans, including the vast majority of citizens of German ancestry.” [7]

Each of these pieces of evidence seems extraordinarily tame from a modern perspective. But in the midst of wartime, in 1918, they were considered treasonous. Fueled by suspicion of socialist-leaning, supposedly radicalized immigrants embedded in the landscape of Philadelphia, the jury took just two hours to convict the staff of the Tageblatt, denying them their right to free speech in the process. [8]

100% of the SBD rewards from this #explore1918 post will support the Philadelphia History Initiative @phillyhistory. This crypto-experiment is part of a graduate course at Temple University's Center for Public History and is exploring history and empowering education to endow meaning. To learn more click here.

"Tageblatt Editor Upholds U-Boats, Derides America." Philadelphia Tribune, Sep. 26, 1918.

Wilson, Woodrow. "Third State of the Union Address, 1915." Wikisource, https://en.wikisource.org/w/index.php?title=Woodrow_Wilson%27s_Third_State_of_the_Union_Address&oldid=4791543.

"Alien Foes Aided Tageblatt, Federal Evidence Discloses." Philadelphia Tribune, Sep. 25, 1918.

Ibid.

"Tageblatt Editor"

"Guilty, Is Verdict for Tageblatt Men in Espionage Case." Philadelphia Tribune, Sep. 28, 1918.

Park, Clyde W. "The Strategic Retreat of the German Language Press." The North American Review 207 (1918): 706-719.

"Guilty"

This is such an interesting post! I've never read about Philadelphia's German American population before, so I appreciate this as an introduction of sorts. I also thought this seemed timely, given the recent release of the film, "The Post," which also addresses suppression of printed speech during wartime. Though the situations between Philadelphia's Tageblatt and the Pentagon Papers differed, this struck me as a fascinating precedent to the events that took place in the 1970s. Great work!

Downvoting a post can decrease pending rewards and make it less visible. Common reasons:

Submit

Thanks, Derek! I wasn't thinking about the 1970s when I wrote the post, but I think you're right that it's a great parallel. The exercise of free speech has taken quite a pummeling- and looks like it will continue to for the foreseeable future.

Downvoting a post can decrease pending rewards and make it less visible. Common reasons:

Submit

Congratulations @cheider! You have completed some achievement on Steemit and have been rewarded with new badge(s) :

Click on any badge to view your own Board of Honor on SteemitBoard.

For more information about SteemitBoard, click here

If you no longer want to receive notifications, reply to this comment with the word

STOPDownvoting a post can decrease pending rewards and make it less visible. Common reasons:

Submit