We continue our study of the episode known as The Battery at the Gate, which concludes Chapter 3 of James Joyce’s Finnegans Wake. This paragraph and the two that precede it originally comprised one unbroken passage. They were printed together when an early draft of this chapter was published in Eugene Jolas & Elliot Paul’s literary journal transition in June 1927. When the first edition of Finnegans Wake came out in 1939, this paragraph was set off from the other two. The latter were finally divorced by Danis Rose & John O’Hanlon in 2010 in The Restored Finnegans Wake.

As we have seen, Joyce based The Battery at the Gate on a story he came across in the Freeman’s Journal about an attempted break-in on Sheriff Street, Dublin. The story appeared on 21 November 1923, just as Joyce was drafting this section:

Richard Whitely, Patrick Farrell, and William Hannon were found guilty at the Commission, charged with having at an early hour of the morning of Sunday, October 7, attempted to break into Pickford’s Store, 6 Upper Sheriff street, with intent to steal goods. It was stated by P.C. Sutton that he and another constable saw the three prisoners at the gate of the store. Hannon was pushing the gate with his shoulder and the others were standing by. When they saw witness they moved to a dark doorway. Whitely was carrying a fender. When witness asked where he got the fender one of the men said “that is for you to find out.” Whitely speaking from the dock, said they were only trying to open a bottle of stout by hammering it against the gate.

Drawing a Cork

The Lord Chief Justice (to the police witness):

―I suppose you know how to draw the cork out of a bottle of stout (a laugh).

“Yes,” replied the witness.

The Lord Chief Justice: Was the sound you heard like trying to get the cork out of a bottle?

Witness: Nothing like it (laughter).

―Freeman’s Journal 21 November 1923

First Draft

The first-draft version of this paragraph consisted of two sentences and was about eight lines long:

How true at first hearing his statement that he had had a lot too much to drink and was falling against the gate yet how lame proceeds his then excuse that he was merely trying to open the bottle of stout by hammering it against the gate for the boots, Maurice Behan, who threw on a pair of pants and came down in his socks without a coat attracted by noise of gunplay was in bed wakened up by loud hammering at the gate. This was not in the least like a bottle of stout which would not rouse him out of sleep but much more like the overture to the last day if anything. ―Hayward 73

Joyce proceeded to expand this brief passage after the usual fashion. By the time the third issue of transition came out it had grown to twenty-six lines.

Another ten or eleven lines had been added to this by 1939, when Finnegans Wake was finally published. The accused man’s drunken binge, which originally consisted of just a single ship hotel, now takes in more than half-a-dozen watering holes. Note also how the single word overture―a piece of music that opens an opera―has now blossomed into a whole suite of musical allusions, running to seven or eight lines.

Dublin Pubs

In the first draft of this passage the Cad (or whoever is trying to break into HCE’s tavern in the middle of the night) is drunk, having had a lot too much to drink. But we are not told where he became intoxicated. In the revised version published by transition we are told that he had too much to drink in a ship hotel. Presumably, this refers to The Ship Hotel and Tavern on Lower Abbey Street, which is mentioned a few times in Ulysses.

By the time Joyce was finished with this passage the Cad’s drinking bout had become a day-long binge, taking in seven establishments:

... the House of Blazes, the Parrot in Hell, the Orange Tree, the Glibt, the Sun, the Holy Lamb and, lapse not leashed, in Ramitdown’s ship hotel

Joyce has once again being consulting Ada Peter’s Dublin Fragments: Social and Historic, which was published in 1925:

Many of the old names of the inns and taverns of Dublin were quaint and curious ... the “House of Blazes” on Aston’s Quay still retained its sinister appellation far on into the nineteenth century ... “The Sun” was not far off in “St. Thomas, his Streete”. “The Orange Tree” was likewise in Castle Street, and “The Glibb” near to “The Sun”. “The Parrot” was in “Hell” ... “The Holy Lamb” was in the old Corn Market. ―Peter 93–96

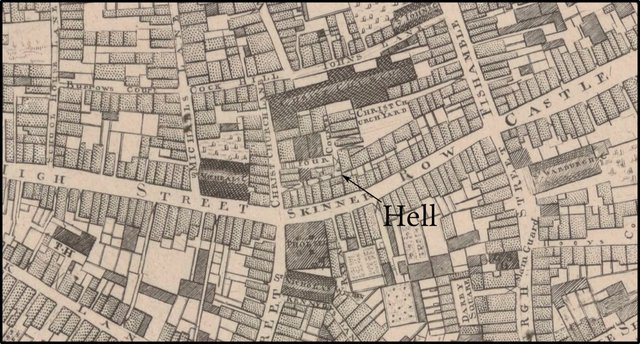

- Hell This was the name of a lane that ran from St Michael’s Hill (at the top of Winetavern Street, where the Christ Church Arch crosses the road) to the old Four Courts, which stood just to the south of Christ Church Cathedral. It appears on John Rocque’s 1756 Map of Dublin. The name was commonly applied to the whole area between Fishamble Street and Christ Church Lane, a place of ill repute in the 18th century.

- Glibt Ada Peter calls this public house The Glibb. Is Joyce’s Glibt a misprint? Did Joyce misread Peter’s Glibb? The Glibb (Glib, or Glibb-Water) was an artificial rivulet created to supply water to St Thomas Street in 1670 (Mink 329).

Maurice Behan

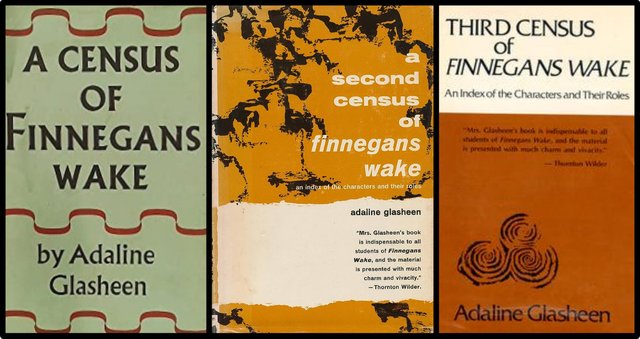

In the first edition of A Census of Finnegans Wake Adaline Glasheen briefly introduces the book’s various characters:

Archetypes of the second rank include ... a man servant, so impenetrably mysterious that I cannot give his name ... He is called Old Joe several times; he is called Mahan; he is called Behan. Probably his name is Maurice Behan, because he is known as Mauritius in the passage 572–573 [RFW 445.31–446.31]. He also appears to be Constable Sacksoun (and variations). Certain commentators have believed that his name is Tom because of the repetition of Tom-Tim that beats through the book, but I see no evidence of this. If he is Constable Sacksoun, it is reasonable to assume―as the authors of A Skeleton Key do assume―that he is also the other policeman, Lally, who is particularly associated with the Four. ―Glasheen 1956:ix ... 83

Unlike Glasheen, we now know that Joyce borrowed the name Maurice Behan from the article in the Freeman’s Journal that inspired The Battery at the Gate:

Maurice Behan, caretaker of the stores, said that he was in bed and heard heavy hammering at the gate.

―Freeman’s Journal, 21 November 1923

Nine years later, when A Second Census of Finnegans Wake was published, Glasheen had acquired a better understanding of HCE’s Man Servant and his rôle in the book, but her ideas are still disparate and all over the shop:

He is “most mousterious”, meaning primitive (Mousterian), a servant-monster like Caliban ... and mysterious. He goes by certain names―Old Joe, Maurice (Moor), Behan-Beham (see Ham)―which are names of the dark races in their servitude. On the other hand, he is called Constable Saxon (and variations) and described as “butterblond”. I assume therefore that he represents any subject race―black Ham, servant to white brothers―white Saxon Harold, servant to Norman William. The Irishman, Stephen Dedalus, describes himself as servant to England, the Saxon ... In the “Mutt and Jute” episode the Man Servant is Mutt.

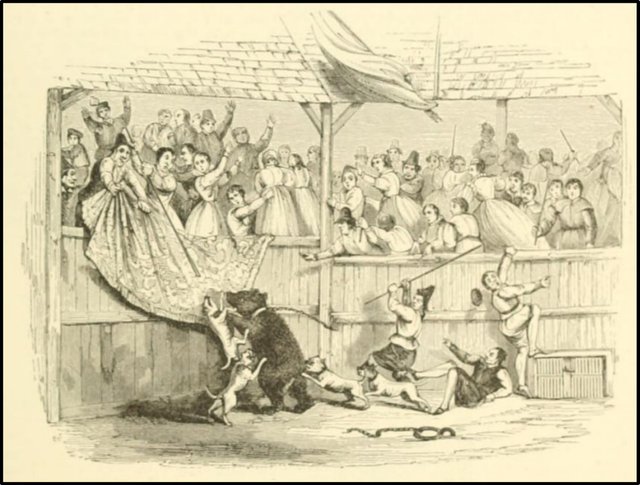

Another name of the Man Servant is Mahan or Mahon ... A queer sort of man he seems to the conqueror: subject races are always queer, they smell funny, they are half animal. A queer sort of “mahan” means, at the same time, a queer sort of animal, for “mahan” and “mahon” ... are anglicizations of the Irish Mathghamhain or “bear”. (Art is also from an Irish [recte Welsh] word for “bear”, but I don’t think Joyce uses it so.) Mahan-as-bear fits, of course, neatly with the fact that the Man Servant is also Sackerson, the bear at the Paris Gardens on the Bankside ... (The bear theme in FW should be looked into.) Since I think FW is about Shakespeare, I am delighted to find the Man Servant associated with both Caliban, the red Indian, and the baited bears of the Bankside. The form of Behan at 333.15 [RFW 257.06], “behomeans”, is nearly an anagram of “Bohemians” and reminds us of the Bohemian bear in The Winter’s Tale. ―Glasheen 1965:166

Glasheen speculates further on this bear theme, before concluding:

There is plainly much to be worked out about the Man Servant, but I really do not think this note is too heavily weighted with bear. Hibernating, waking, the bear makes a very fair symbol of resurrection, personal or national; Bruin is always the gull in Reynard stories; the bear can be made to dance and ride a bicycle; he walks upright and on all fours, exemplifying inferior races which seem half-bestial to their masters.

The Man Servant represents not only the subject races of modern history, but the more primitive races of pre-history. He is “mousterious” and in the Mousterian period, Neanderthal man was giving up the ghost. More than that, the Man Servant as bear represents, I think, that most subject of all kingdoms, the animal. The bear was here on earth before man, just as the Utah Indian was on the American continent and Caliban in Bermuda before Prospero or Trinculo-Stephano came to outsmart him. The Man Servant is not only subject, he is dispossessed, and as dispossessed ties onto one of the great themes of FW, a theme which includes the Irish ass, St Patrick (when he was a slave with four masters), Esau, Ham, Hamlet, Havelok, and even Adam, dispossessed of Eden and become a toiler. ―Glasheen 1965:166–167

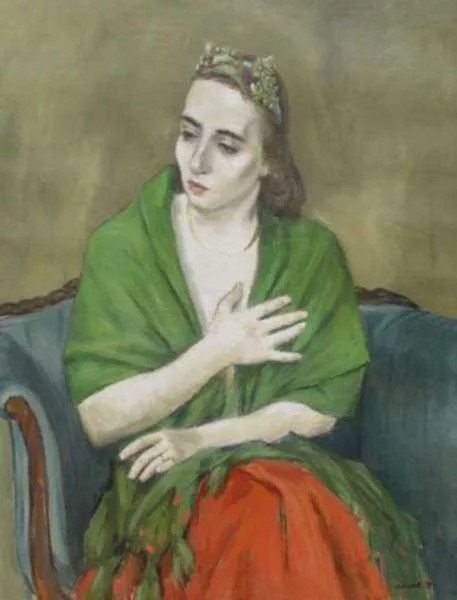

Even as late as 1977, when the definitive Third Census of Finnegans Wake was published, Glasheen was still struggling to pin down this character:

... my understanding of him is too wavery and intermittent for summary. He is a nasty, old, drunk, abased handyman at the inn, “curate” at the bar. By times he represents the dark usurped races―Utah Indian, Moor as Maurice, brown as bear or Mahan, black as Jo, Behan-Beham (see also Ham, Black Man), or Mutt as racial mongrel.

At other times, (by what mechanism?) he is “butterblond” Constable Sacksoun, also old, drunk, abased, nasty, and a policeman and informer, hateful and hating, who does his master’s dirty work, as the black does his physical dirty work.

The Man Servant “most mousterian” (i.e., Neanderthal) is also the usurped, our dead ancestors, or he is a living primitive―Stone Age man of Africa, Nazi, or American redneck. He is also our ancestors, the animals, especially extinct animals like dragons, snakes-in-Ireland, baited bears, mastodon and Behemoth. Perhaps the Man Servant is the old age of Milton’s Satan. ―Glasheen 1977:184–185

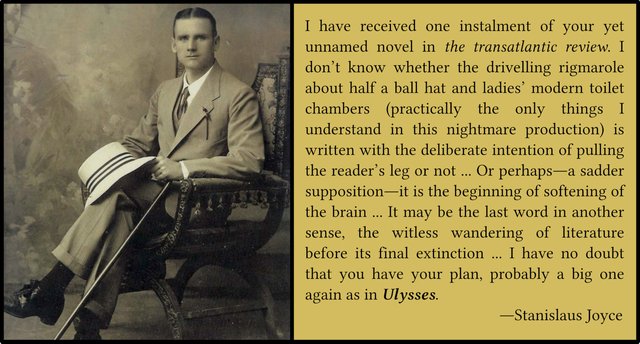

Stephen Hero

It may not or may be relevant but Finnegans Wake is not the first of James Joyce’s works to feature a character called Maurice. In Joyce’s first novel, the unfinished and autobiographical Stephen Hero, Stephen’s brother and sounding board is called Maurice. This character was based on Joyce’s closest brother Stanislaus, who did indeed serve as a sympathetic confidant during James’s sentimental education. Joyce eventually abandoned Stephen Hero and recast it as A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man. In this form the character of Maurice has all but disappeared, making just one brief appearance in Chapter II.

The origin of Stephen Hero is recounted by Richard Ellmann in his biography of Joyce. It all began with a short, highly-condensed autobiographical essay Joyce wrote in January 1904:

At the beginning of 1904 he learned that Eglinton and another writer he knew, Fred Ryan, were preparing to edit a new intellectual journal named Dana after the Irish earth-goddess. On January 7 he wrote off in one day, and with scarcely any hesitation, an autobiographical story that mixed admiration for himself with irony. At the suggestion of Stanislaus, he called it ‛A Portrait of the Artist,’ and sent it to the editors. This was the extraordinary beginning of Joyce’s mature work. It was to be remolded into Stephen Hero, a very long work, and then shortened to a middle length to form A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man. But this process took ten years ...

The essay narrative was duly submitted to Eglinton and Ryan, and by them duly rejected. Eglinton told Joyce, ‛I can’t print what I can’t understand,’ and objected to the hero’s sexual exploits, whether with the dream lady of his litany or with the real prostitutes. Joyce took this rejection as a challenge to make the fictional history of his own life the call to arms of a new age. ―Ellmann 144 ... 147

Stanislaus Joyce takes up the story in his diary:

2nd February: 1904: Tuesday. Jim’s birthday. He is twenty-two [to]day. He was up late and did not stir out all day, having a bad cold. He has decided to turn his paper into a novel, and having come to that decision is just as glad, he says, that it was rejected. The paper ... was rejected by the editors, Fred Ryan and W. Magee (‛John Eglinton’) because of the sexual experiences narrated in it. Jim thinks that they rejected it because it is all about himself, though they professed great admiration for the style of the paper. They always admire his style ... Jim is beginning his novel, as he usually begins things, half in anger, to show that in writing about himself he has a subject of more interest than their aimless discussion. I suggested the title of the paper ‛A Portrait of the Artist’, and this evening, sitting in the kitchen, Jim told me his idea for the novel. It is to be almost autobiographical, and naturally as it comes from Jim, satirical. He is putting a large number of his acquaintances into it, and those Jesuits whom he has known. I don’t think they will like themselves in it. He has not decided on a title, and again I made most of the suggestions. Finally a title of mine was accepted: ‛Stephen Hero,’ from Jim’s own name in the book ‛Stephen Dedalus.’ The title, like the book, is satirical. Between us we rechristened the characters, calling them by names which seemed to suit their tempers or which suggested the part of the country from which they come. Afterwards I parodied many of the names: Jim, ‛Stuck-up Stephen’; Pappie, ‛Sighing Simon’; myself, ‛Morose Maurice’; the sister, ‛Imbecile Isobel’; Aunt Josephine (Aunt Bridget), ‛Blundering Biddy’; Uncle Willie, ‛Jealous Jim.’ ―Healey 11–12 : Ellmann 152–153

Joyce worked on Stephen Hero over the next few years. By March 1906 he had written 914 pages and 25 chapters. He is thought to have abandoned the work in late June or early July 1906, when he was living in Trieste (Norburn 26). Only a fragment of the manuscript survives. The opening 518 pages have been lost. The earliest extant fragment begins in the middle of Chapter XV and the last pages are from Chapter XXVI. In September 1907, after completing Dubliners, Joyce began to recast it (Norburn 37).

In Finnegans Wake it is the character of Shaun who is most commonly associated with Stanislaus. I do not think there is anything of Stanislaus in HCE’s elderly Man Servant. It is probably a coincidence that the same name Maurice was used for these two characters.

Music

In the first draft of this passage Maurice Behan gave evidence that the noise that roused him from his bed did not sound like someone trying to open a bottle of stout:

This was not in the least like a bottle of stout which would not rouse him out of sleep but much more like the overture to the last day if anything. ―Hayward 73

As we have seen, Joyce was inspired by the musical meaning of the word overture to expand this for transition:

This battering babel allower the door and sideposts, he always said, was not in the very remotest like the belzey babble of a bottle of boose which would not rouse him out o’slumber deep but reminded him loads more of marses of foreign musikants’ instrumongs or the overthrew to the third last days of Pompery, if anything. ―Jolas & Paul 42

By 1939, however, he has added several more lines of musical allusions, many of them with warlike connotations:

This battering babel allover the door and sideposts, he always said, was not in the very loutest like the belzeybabble of a bottle of boose which would not rouse him out o’ slumber deep but reminded him loads more of the martiallawsey marses of foreign musikants’ instrumongs playing Delandy is Cartager on the ragnar rock to Dulyn or the overthrewer to the third last days of pompery, if anything. And that after this most mooningless knockturn the young reine came down desperate and the old liffopotamus herself started ploring all over the plain, as mud as she cud be, ruinating all the bouchers’ schurts and the backers’ wischandtugs so that, be the chandeleure of the Rejaneyjailey, they were all nigh wasching the walters off, the weltering walters off. Whyte?

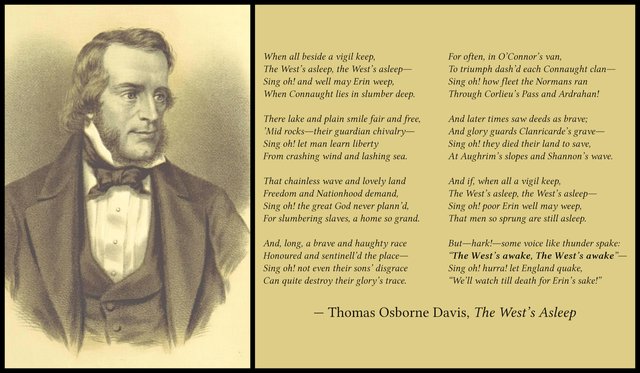

o’ slumber deep When Connaught lies in slumber deep, a line from the patriotic ballad by Thomas Osborne Davis The West’s Asleep (often known incorrectly as The West’s Awake, but alluded to nine lines above as the wastes u’sleep).

martiallawsey La Marseillaise, the French national anthem―a martial song.

marses marches, with Mars, the god of war.

German: Musikant, musician.

instrumongs instruments. English Dialect: mong, a muddle or confusion : a mingling or mixture.

overthreweroverture, overthrow.

Delandy is Cartager When Hosty’s ballad was given its première in the previous chapter, a Mr Delaney (Mr Delacey?) played the horn. I am not aware of any pieces of music about the fall of Carthage (Carthago delenda est). Henry Purcell’s opera Dido and Aeneas and Hector Berlioz’s grand opera Les Troyens are probably the best known works associated with the ancient city.

the ragnar rock to Dulyn The Rocky Road to Dublin, a 19th-century Irish song. The lyrics were written by the Irish poet D K Gavan. Mr Deasy recites a few lines in the Nestor episode of Ulysses.

Old Norse: Ragnarǫk, Fate of the Gods. In Norse mythology Ragnarök is the cataclysmic end of the world. It will culminate in a great battle in which many of the gods will die. After this the world will begin anew. The word is often translated inaccurately as Twilight of the Gods―in German, Götterdämmerung―which Richard Wagner chose as the name of the concluding part of his operatic cycle Der Ring des Nibelungen (The Ring of the Nibelung).

the third last days of pompery Edward Bulwer-Lytton’s novel The Last Days of Pompeii (1834) is the obvious reference, but there may also be an allusion to Giovanni Pacini’s opera L’ultimo giorno di Pompei [The Last Day of Pompeii] (1825). It is thought that the opera inspired Karl Brullov’s painting of the same name (1830–33), which in turn inspired Bulwer-Lytton’s novel. John Gordon also sees an allusion to Pompey the Great, who was thrice elected Consul and was given three triumphs, before being overthrown by Caesar.

mooningless knockturn nocturne, a musical form invented by the Dublin-born composer John Field. mooningless could also include an allusion to Beethoven’s Moonlight Sonata. The first edition had nooningless.

Rejaneyjailey Latin: Regina Coeli, Queen of Heaven, a musical antiphon addressed to the Virgin Mary. Over the centuries this short Medieval text has been set to music by numerous composers, including Victoria, Palestrina, Lully, Mozart and Brahms. There is also a jail in Rome known as Regina Coeli, which had once been a convent. According to John Gordon, be the chandeleure of Rejaneyjailey [by the chandelier of the Queen of Heaven] means by the light of the moon (Gordon 64.19).

There are other musical allusions scattered elsewhere in this paragraph:

Fifthly ... fourth ... third Musical intervals?

truetoned In the 1930s Truetone was a brand name used by the Western Auto Supply Company of Kansas City for radios, phonographs, televisions and guitars.

the engine of the laws declosed unto Murray The Angel of the Lord declared unto Mary, the opening words of the Angelus, which is announced by the ringing of bells.

fillthefluthered Percy French’s song Phil the Fluter’s Ball. In his short story Grace (Dubliners) Joyce coined the word peloothered, meaning very drunk, but fluthered is genunie Irish slang.

he dreamed that he’d wealthes in mormon halls I Dreamt That I Dwelt in Marble Halls, an aria from Michael William Balfe’s opera The Bohemian Girl. In 1922 a silent movie inspired by the opera was released.

Viconian Structure

The last five lines of this paragraph anticipate Anna Livia Plurabelle, the concluding chapter in Book I. Note that the final version of this paragraph comprises precisely four sentences (followed by the single word Whyte?) Are we to interpret these along Viconian lines? It is a bit of a stretch, perhaps, but the first sentence does hark back to the ancient times of Hengist and Horsa : the second sentence, with Sir Bunchamon, the tiltyard, Open Sesame and The Bohemian Girl, evokes the medieval world of Romance : the third sentence alludes to the last day : and the fourth sentence, as we have just said, unmistakably foreshadows the ricorso storico that brings Book I to an end.

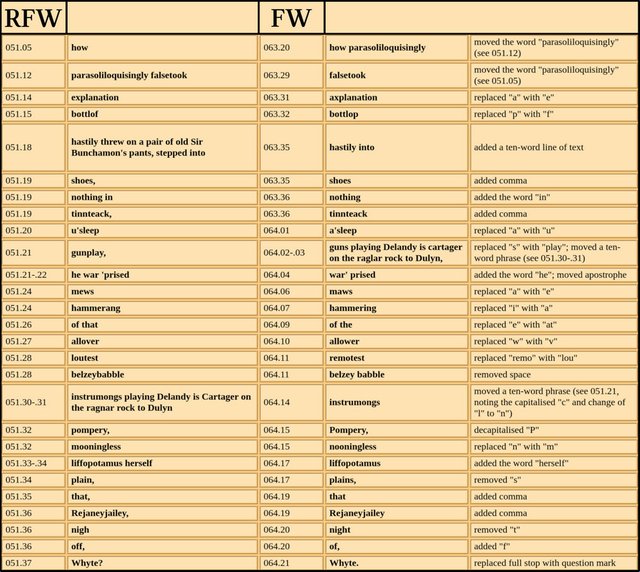

Transmission Errors

When this passage was being prepared for final printing, someone inadvertently omitted a ten-word line:

threw on a pair of old sir Bunchamon’s pants, stepped ... ―RFW 051.18

The first edition of 1939 reads:

... Maurice Behan, who hastily into his shoes ... ―FW 063.35

Joseph Campbell & Henry Morton Robinson spotted this error and supplied the missing line from transition (Campbell & Robinson 73, 366). The fact that the missing words constitute a complete line in transition suggests that a copy of transition was consulted when this passage was being prepared for printing. Whoever was consulting transition skipped over this line. Who was the guilty party? We can acquit the typesetter, because the final version of this passage is different from the version that appeared in transition:

boots about the swan Maurice Behan, who hastily

threw on a pair of old sir Bunchamon’s pants, stepped

into his shoes and came down to the tiltyard from thetransition June 1927

for the boots

about the swan, Maurice Behan, who hastily into his shoes with

nothing his hald barra tinnteack and came down with homp,

shtemp and jumphet to the tiltyard from theFinnegans Wake 1939

Note that the first edition also omitted the word in before his hald ... Joyce must have been the guilty party.

Another ten-word phrase was misplaced. The words:

playing Delandy is Cartager on the ragnar rock to Dulyn ... ―RFW 051.30–31

were moved to an earlier line, and slightly altered to:

guns playing Delandy is cartager on the raglar rock to Dulyn, ―FW 064.03

There are about two dozen other minor differences between the corrected edition of Finnegans Wake (Faber and Faber 1950 : Viking Press 1958) and The Restored Finnegans Wake (2010):

And that’s as good a place as any to beach the bark of our tale.

References

- Joseph Campbell, Henry Morton Robinson, A Skeleton Key to Finnegans Wake, Harcourt, Brace and Company, New York (1944)

- Thomas Osborne Davis, The West’s Asleep, The Spirit of the Nation, Second Edition, Revised, Pages 19–20, James Duffy, Dublin (1844)

- Adaline Glasheen, A Census of Finnegans Wake, Northwestern University Press, Evanston, Illinois (1956)

- Adaline Glasheen, A Second Census of Finnegans Wake, Northwestern University Press, Evanston, Illinois (1963)

- Adaline Glasheen, Third Census of Finnegans Wake, University of California Press, Berkeley, California (1977)

- David Hayman, A First-Draft Version of Finnegans Wake, University of Texas Press, Austin, Texas (1963)

- George H Healey (editor), The Complete Dublin Diary of Stanislaus Joyce, Cornell University Press, Ithaca, New York (1971)

- Eugene Jolas & Elliot Paul (editors), transition, Number 3, Shakespeare & Co, Paris (1927)

- James Joyce, Finnegans Wake, The Viking Press, New York (1958, 1966)

- James Joyce, James Joyce: The Complete Works, Pynch (editor), Online (2013)

- Louis O Mink, A Finnegans Wake Gazetteer, Indiana University Press, Bloomington, Indiana (1978)

- Ada Peter, Dublin Fragments: Social and Historic, Hodges Figgis & Co, Dublin (1925)

- Danis Rose, John O’Hanlon, The Restored Finnegans Wake, Penguin Classics, London (2012)

Image Credits

- Truetone Radio: © Radio Attic, Fair Use

- I Dreamt That I Dwelt in Marble Halls: Byam Shaw (artist), J Cuthbert Hadden, The Great Operas: The Bohemian Girl: Balfe, T C & E C Jack, New York (1907), Public Domain

- Upper Sheriff Street: Anonymous Photograph, Public Domain

- Hell: John Rocque (cartographer), An Exact Survey of the City and Suburbs of Dublin, Dublin (1756) : Bibliothèque nationale de France, Paris, Public Domain

- Sackerson the Bear: Robert William Buss (etcher), Charles Knight, The Pictorial Edition of the Works of Shakspere, Volume 1, Page 160, Virtue & Co, London (1867), Public Domain

- Adaline Glasheen: Alexander Brook (artist), © Childs Gallery, Fair Use

- Stanislaus Joyce: Anonymous Photographer, Public Domain

- Thomas Osborne Davis: After A M Sullivan & P D Nunan, _Atlas and Cyclopedia of Ireland, Part 2: The General History, Pages 204–205, Murphy & McCarthy Publishers, New York (1905), Public Domain

- The Last Day of Pompeii: Karl Brullov (artist), State Russian Museum, Saint Petersburg, Public Domain

- The Washers at the Ford © Heather Ryan Kelley (artist), Ransom Center Collection, Harry Ransom Center, The University of Texas at Austin, Fair Use

- Finnegans Wake Errata: © Raphael Slepon (designer), Fair Use

Useful Resources

- John Rocque’s Map of Dublin (1756)

- John Rocque’s Map of Dublin

- Jorn Barger: Robotwisdom

- Joyce Tools

- FWEET

- The James Joyce Scholars’ Collection

- FinnegansWiki

- James Joyce Digital Archive