Chapter I.3 of James Joyce’s Finnegans Wake—the Humphriad II—is a journalistic investigation into the HCE affair, especially HCE’s memorable encounter in the Phoenix Park with the Cad with a Pipe. We continue our study of the episode known as the Plebiscite—RFW 046.16-049.29—which documents the people’s response to the affair. What does public opinion say?

The paragraph we are now studying is one of four short paragraphs that were originally published as a single long paragraph when an early draft of this chapter appeared in June 1927 in Eugene Jolas & Elliot Paul’s literary journal transition. These paragraphs, which form a sort of introduction to the plebiscite proper, remained yoked together when the first edition of Finnegans Wake was published in 1939. Their independence was restored to them when Danis Rose & John O’Hanlon brought out The Restored Finnegans Wake in 2010. All three versions of the present paragraph—1927, 1939, 2010—are nearly identical. There is only a single small discrepancy between the first two: the first edition of 1939 has Lou! Lou! instead of Lou! lou! The restored edition has Lou! lou!, but it also includes another, more substantial emendation:

His beneficiaries are legion in the part he created: they number up his years. Greatwheel Dunlop was the name was on him: (1927, 1939)

His beneficiaries are legion: they number up his years. Greatwheel Dunlop was the name was on him in the part he created: (2010)

This paragraph was not part of the very first draft of The Plebiscite (Hayman 71). Between December 1923 and early 1927, however, Joyce expanded this section, before preparing a typescript of the entire chapter. In that typescript we have one of the earliest surviving drafts of this paragraph:

The Thing Mod have undone him: and his mad Thing has done him Man. His beneficiaries are Legion; they number up his years. Greatwheel Dunlop was the name on him. Behung, we are his bisaacles. Was hollyday in his house, so was he priest and king to that: [BLANK] came, envy saw, ivy conquered. They have waved his green boughs o’er him or they have torn him limb for limb. For his mortification and expiration and damnation and annihilation (James Joyce Digital Archive)

This is already very close to the published version:

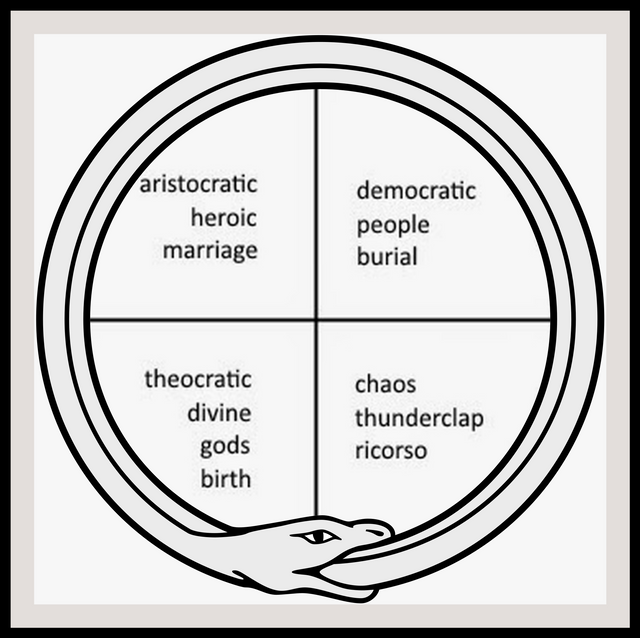

The Viconian Cycle

The focus of this paragraph is the Viconian Cycle, which is woven into the structure of Finnegans Wake:

According to Giambattista Vico’s philosophy of history, human civilization passes through three phases before collapsing into the chaos of uncivilization. But this chaos flows back into the first phase, and the Viconian Cycle begins anew:

| Age | Description | Institution |

|---|---|---|

| Theocracy | Age of Gods | Birth |

| Aristocracy | Age of Heroes | Marriage |

| Democracy | Age of Men | Burial |

| Ricorso, or Reflux | Collapse into Chaos | - |

In Finnegans Wake, the Viconian Cycle has four quadrants, corresponding loosely to the four books into which the work is divided. Here is how Roland McHugh summarized the relevance of Vico to a reading of Finnegans Wake:

Giambattista Vico (1668-1744) is the author of Principi di Scienza Nuova (The New Science), in which is expounded his theory that a common cyclical pattern identifies the histories of diverse nations. The cycle consists of (1) the age of gods, represented in primitive society by the family life of the cave, to which God’s thunder had driven man; (2) the age of heroes, characterized by the continual revolutionary movements of the plebeians against the patricians; (3) the age of people, the final consequence of the leveling influence of revolutions. The three ages are typified by the institutions of birth, marriage, and burial, respectively, and followed by a short lacuna, the ricorso (resurrection) linking the third age to the first of a subsequent cycle. These four periods are illustrated by the four books into which Finnegans Wake is divided and also by concise references to attributes of the ages (e.g., their institutions). (McHugh 2006:xiv-xv)

In his notebooks and drafts Joyce represented this cycle with a siglum known as the Mandala:

Mandala: the endless Viconian cycle that keeps the world and Finnegans Wake turning. This siglum represents a wheel. Joyce liked to think that in Finnegans Wake he succeeded in squaring the circle, a problem which Bloom had failed to solve: Finnegans Wake has four parts, like a square, but it is circular, like the ouroboros. The Mandala siglum—which is named at RFW 449.31, mandelays—encapsulates this idea. Traditional mandalas of ancient India typically combined these two basic shapes. They were representations of the cosmos, and were used as objects of contemplation during meditation. Joyce, however, makes his Mandala a wheel by adding four spokes (Hart 77). It also resembles the crosshairs, or reticle, found in the eyepiece of telescopes, microscopes and guns—objects which are also used to focus the mind on something.

These few lines contain several allusions to the Mandala, with its four quadrants:

Greatwheel Dunlop John Boyd Dunlop was the Scottish inventor who developed the first successful pneumatic tyres—originally for his son’s tricycle—in Belfast, Ireland, in 1887. Two years later Dunlop and his financier Harvey du Cros opened the world’s first pneumatic tyre factory in Upper Stephen Street, Dublin.

John Gordon suggests also big wheel, meaning an important person, though the earliest use of this expression according to the OED was in 1942 (Gordon 58.3-4).

There was a Ferris wheel known as The Great Wheel in London between 1895 and 1907.

Finally, it is just possible that there is an allusion to a wheel of Dunlop cheese, anticipating the Mastication of the Host in the following paragraph.

bisaacles bicycles, with a hint also of testicles. John Gordon offers the following explanation for Isaac’s presence in this portmanteau word:

58.4: “all we are his bisaacles:” that is, as bicycles, relatively small-wheeled descendants—like Isaac from Abraham—of the big wheel Dunlop, whose rubber tires were fitted on bicycles. (Gordon 58.4)

- In my opinion, however, bisaacles actually refers to Isaac’s sons Jacob & Esau—standing in for Shem & Shaun—the two (bi-) little (-le) Isaacs.

French: besicles, spectacles. In his old age Isaac was blind—eye-sick. In Finnegans Wake, Shem, like Joyce, has poor eyesight.

French: bissac, satchel, shoulder bag, scrip, wallet. In French slang, this word is a vulgar term for the female genitalia—cunt, vulva—which is surely relevant in the context of Dunlop’s descendants. So bisaacles is hermaphroditic.

ulvy came, envy saw, ivy conquered. Lou! lou! The obvious allusion is to Caesar’s Veni, Vidi, Vici [I came, I saw, I conquered], but the Viconian pattern of three ages followed by a dissolution is also discernible. The final words may also allude to loo, meaning a toilet, where one’s water is recycled, like Vico’s history.

muertification and uxpiration and dumnation and annuhulation mortification and expiration and damnation and annihilation, as Joyce originally wrote. Each of these terms is a sort of synonym for death, but the first three may also embody the institutions that characterize the three Viconian Ages—birth, marriage and burial (McHugh 1976:5)—while the final term embodies the ouroboros:

Latin: puer, boy, child (birth). But this is a bit of a stretch. Spanish: muerte, death, is a more obvious allusion.

Latin: uxor, wife (marriage).

Latin: humere, to bury (burial). Another stretch, but why else did Joyce alter his original damnation to dumnation?

Latin: annulus, ring (Viconian Cycle).

The final word also incorporates ululation, a wailing or lamentation—as though They are grieving for the dead—which is immediately taken up by the opening words of the following paragraph: With schreis and grida.

Who are They? The concatenation of sesquipedalian Latinate terms ending in -ation is characteristic of The Twelve, the Wake’s resident jury and Greek chorus. Their siglum, which represents a dial—the face of a watch or clock—is similar to the Mandala. This is appropriate, as both share a temporal element. The Twelve may even be said to embody Time, just as The Four Old Men embody Space.

The Golden Bough

We have already met the Scottish mythologist James Frazer and his opus magnum The Golden Bough. Joyce drew on this work when he recast the ballad Finnegan’s Wake as the novel Finnegans Wake. As Roland McHugh and Anthony Burgess noted, Finnegan’s Wake is, at its core, a death-and-resurrection story. This brings it within the orbit of many ancient myths, in which a heroic figure or deity dies only to be subsequently resurrected: Jesus, Osiris, Adonis, Attis, Tammuz, among others.

Several of these figures appear in Finnegans Wake, Jesus and Osiris being particularly prominent. In Finnegan’s Wake whiskey is the cause of both Finnegan’s death and his resurrection. The word whiskey comes from the Irish uisce beatha, or water of life.

Tim Finnegan’s fall is preceded by his rise in the world. This too is a prominent motif in both myth and literature. In ancient Greek tragedy the hero’s fall was typically precipitated by his hubris—overweening pride—which caused him to soar too high. The same idea can also be found in a Judaeo-Christian setting in the Fall of Lucifer and the Fall of Man. The former was precipitated by Lucifer’s pride, the latter by man’s desire to become like God. In literature, the protagonist of Henrik Ibsen’s play The Master Builder describes a similar trajectory.

Another theological and mythical motif that is hinted at in the lyrics of Finnegan’s Wake is the Mastication of the Host, or Eating the God, which Joyce also found in The Golden Bough:

We have now seen that the corn-spirit is represented sometimes in human, sometimes in animal form, and that in both cases he is killed in the person of his representative and eaten sacramentally. (Frazer 479-480)

In time, the literal sacrifice and cannibalism of a human victim was replaced by a figurative substitute, such as the bread and wine of the Catholic Mass:

The custom of eating bread sacramentally as the body of a god was practised by the Aztecs before the discovery and conquest of Mexico by the Spaniards. (Frazer 488)

In Finnegan’s Wake Mrs Finnegan calls for lunch, and the items on the menu are enumerated: tay [tea], cake, tobacco and whiskey punch. The eating and drinking take place in the presence of Tim’s “corpse”, so it is not much of a stretch to see in this another symbolic instance of the Mastication of the Host, with Tim as the sacrificial victim or god:

We are then presented with a full-length portrait of Shem and at the same time introduced to the big food-theme which plays so important a part in the story. At that wake of Finnegan, the flesh to be devoured was that of the dead hero; with the coming of the brothers, it is the substance of the father HCE which must nourish the new rulers. Shem eats all the wrong food: he will not take the Irish salmon of Finn MacCool, for instance, but prefers some foreign muck out of a tin. (Burgess 18)

The Mastication of the Host, which was introduced at RFW 005.27 ff, is clearly alluded to in the next paragraph (RFW 047.01-12).

The definitive treatment of the impact of The Golden Bough on Finnegans Wake can be found in Chapter XIV of John B Vickery’s The Literary Impact of The Golden Bough (1973). Vickery was Professor of English at the University of California, Riverside.

The closing lines of the paragraph we are now studying comprise one of the Wake’s clearest allusions to The Golden Bough:

As hollyday in his house so was he priest and king to that: ulvy came, envy saw, ivy conquered. Lou! lou! They have waved his green boughs o'er him as they have torn him limb from lamb. For his muertification and uxpiration and dumnation and annuhulation.

As early as 1959 James Atherton drew attention to these lines in The Books at the Wake:

In addition to the works of Budge Joyce probably used Frazer’s The Golden Bough, and seems, like his friend T. S. Eliot, to ‛have used especially the two volumes Atthis, Adonis, Osiris’. [Footnote: See T. S. Eliot, The Waste Land, notes.] The Golden Bough is certainly being used in ‛As hollyday in his house so was he priest and king ... They have waved his green boughs o’er him as they have torn him limb from lamb’ (58.5). The word ‛boughs’ gives a key to the title of Frazer’s work, from which the words ‛priest and king’ are a quotation ... The bough here is holly instead of mistletoe, and the god is killed as Caesar, but the victim is the sacrificial lamb ... Mistletoe, of which the Golden Bough was made, is mentioned several times in the Wake. (Atherton 193-194 ... 199)

I do not know whether Atherton is correct when he claims that priest and king is a quotation from The Golden Bough—there are too many different editions to be sure, but I could not find it. Most commentators see this phrase as an allusion to something William Blake wrote in a letter to his friend George Cumberland four months before his death. This is confirmed by a note Joyce made in a notebook he compiled between November 1925 and February 1926 (VI.B.13):

... the Mind, in which every one is King and Priest in his own House. (Symons 236)

Atherton did not include The Golden Bough among what he called the structural books of Finnegans Wake, but Vickery disagrees:

Frazer’s work constitutes a central aspect of Finnegans Wake, which might easily merit its inclusion among the structural books of the Wake. (Vickery 409)

Vickery’s commentary on this passage is worth quoting:

The ballad’s musical attack and ritual expulsion and death of HCE is matched on the level of reported action by Hosty’s death. To emphasize the sexual aspect as a means of underscoring Parnell’s involvement in the scene, he is identified as follows: “Greatwheel Dunlop was the name was on him in the part he created: behung, all we are his bisaacles. As hollyday in his house so was he priest and king to that: ulvy came, envy saw, ivy conquered. Lou! Lou! They have waved his green boughs o’er him as they have torn him limb from lamb. For his muertification and uxpiration and dumnation and annuhulation” (58:3-9). Here “behung” is a description of genitality as well as mortality. In this Joyce resembles Frazer in that the dying god too has his phallic and fertile aspect in addition to his suffering and disappearing form. The suggestion that “we” are all cyclical versions of “Greatwheel Dunlop” further develops the universal, archetypal nature of HCE and the drama he enacts in the Wake. Thus, Parnell is not merely an Irish scapegoat victimized by society’s expulsion of its own impulses to illicit passion. He is also Frazer’s dying god embodied in human form from its earliest times. This is testified to by the collocation of holly, priest, king, ivy, and green boughs. (Footnote: The Golden Bough II, 122, 251; V, 66, 72ff., VI, 88, 110, 112; VII, 1ff., 40ff.] (Vickery 415)

The presence of Charles Stewart Parnell is indicated by the phrase ivy conquered. Ivy Day, 6 October, commemorated the death of Parnell on that date in 1891. One of Joyce’s short stories in his collection Dubliners is set on Ivy Day.

There is no definitive evidence that Joyce ever read The Golden Bough. It was not among the books that constituted his Trieste and Paris Libraries. He may have been aware of its contents at second hand. And if he did read Frazer at first hand, no one can be sure which edition he read. The definitive third edition (1906-1915) is an encyclopaedia of twelve volumes, while the abridged edition of 1922 condenses everything into a single volume.

These lines do not quote from any specific passage in The Golden Bough. Rather, they draw on several motifs that Frazer explores throughout the work.

- behung be hanged! behold! This word may also incorporate a reference to Frazer’s Hanged God (Atherton 199). Frazer’s most extended treatment of this motif can be found in Chapter V of the fifth volume in the third edition—one of the two volumes Atherton suspected Joyce had consulted. There are, however, no clear references to that chapter in the present paragraph. T S Eliot mentions the Hanged Man in the opening section of The Waste Land, which is known as “The Burial of the Dead”. This may be where Joyce came across the motif. In his own endnotes, Eliot writes:

To another work of anthropology I am indebted in general, one which has influenced our generation profoundly; I mean The Golden Bough; I have used especially the two volumes Atthis Adonis Osiris ...

I am not familiar with the exact constitution of the Tarot pack of cards, from which I have obviously departed to suit my own convenience. The Hanged Man, a member of the traditional pack, fits my purpose in two ways: because he is associated in my mind with the Hanged God of Frazer, and because I associate him with the hooded figure in the passage of the disciples to Emmaus in Part V. (Eliot 53 ... 54, Note to Line 46)

Loose Ends

And finally, let us tie up some loose ends.

- Thing Mod The Thingmote was the hill between St Andrew’s Street and Suffolk Street where the Norsemen who governed Medieval Dublin held their thing, or assembly. In Scotland the Old Norse: mót, meeting, was adopted as mòd to describe a competitive festival of Gaelic song and culture, similar to the Eisteddfod of the Welsh bards. Joyce noted Gaelic Mod in VI.B.14:168i.

Mod have might have.

done him man done him in. I have no idea why Joyce altered this.

His beneficiaries are legion: they number up his years Joyce’s note VI.B.20:72d reads: no of beneficiaries / = age of king. Raphael Slepon interprets this as follows:

the number of his beneficiaries equals the number of years he has lived ... his beneficiaries count the years he has left to live (FWEET)

His years are numbered means He is doomed to die, but I have no idea where Joyce got the idea that the age of a king is equal to the number of his beneficiaries. What does that even mean?

in the part he has created Here Joyce has borrowed the theatrical acceptation of created—said of the performer who was the first to play a particular rôle—from Charles E Pearce’s Sims Reeves, Fifty Years of Music in England, a biography of the English operatic and oratorio tenor Sims Reeves:

Meanwhile Sims Reeves was through illness unable to fulfil his engagements. However, during February he recovered sufficiently to sing at Exeter Hall in Elijah. Santley for the first time essayed the title-rôle, Mr. Chorley observing that “since Herr Staudigl ‛created’ the part (with the exception of Signor Beletti) we have not heard a first appearance as Elijah on the whole so satisfactory.” (Pearce 206)

- hollyday holiday, holly. In an earlier article we met the Wren Boys, who are also discussed by Frazer:

On Christmas Day or St. Stephen’s Day the boys hunt and kill the wren, fasten it in the middle of a mass of holly and ivy on the top of a broomstick, and on St. Stephen’s Day go about with it from house to house ... (Frazer 537)

Danish: ulv, wolf.

Latin: ulva, sedge.

French: loup, wolf.

they have torn him limb from lamb ... limb from limb. In the immediate context, this clearly alludes to the ritual killing of the king that plays such a prominent rôle in The Golden Bough. This whole paragraph epitomizes this ritual, in which the king is first worshipped and raised up before being sacrificed for the good of the community. The Biblical allusions—My name is Legion: for we are many (Mark 5:9), Isaac—remind us that Jesus Christ was such a king and are carried over into the next paragraph. But the parody of Caesar’s I came, I saw, I conquered reminds us that he too was a king—of sorts—sacrificed for the common good.

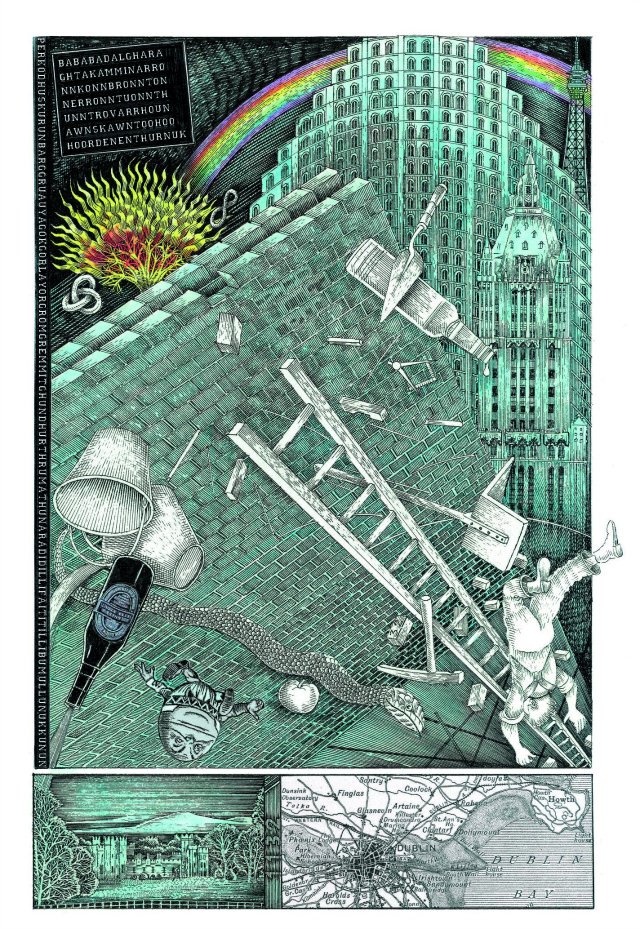

In a broader context, the dismemberment of the Bögg—an effigy of winter—during the spring festival of Sechseläuten in Zurich, and the dismemberment of Osiris by Set in Egyptian mythology are most relevant. Frazer alludes to Sechseläuten in The Golden Bough, though not by that name (Frazer 614). As we shall see, there are clear allusions to the Bögg in the next paragraph.

In Greek mythology, Dionysus (Bacchus) was torn limb from limb by his raving maenads. The word madthing may include a reference to these mad women. But one scholar, Arthur T Broes, sees this as an allusion to Jonathan Swift’s collapse into at the end of his life:

“His Thing Mod have undone him: and his madthing has done him man” (58.1) is simultaneously an allusion to Earwicker, whose “sin” or “madthing” having been discovered, has “done him in,” and Swift, whose madness had similarly undone him. In his mental disorder, accompanying illnesses and demise, Swift becomes an exemplar of the inescapable lot of man ... (Broes 133)

- lamb The sacrificial lamb—Christ again—is too well known to require further comment.

And that’s as good a place as any to beach the bark of our tale.

References

- James S Atherton, The Books at the Wake: A Study of the Literary Allusions in James Joyce’s Finnegans Wake, The Viking Press, New York (1960)

- Arthur T Broes, Swift the Man in Finnegans Wake, ELH, Volume 43, Number 1, Pages 120-140, The Johns Hopkins University Press, Baltimore, Maryland (1976)

- Anthony Burgess, A Shorter Finnegans Wake, Faber & Faber Limited, London (1966)

- T S Eliot, The Waste Land, Boni and Liveright, New York (1922)

- James George Frazer, The Golden Bough: A Study in Magic and Religion, Third Edition, Volume V of XII, Part IV: Adonis, Attis, Osiris, Volume 1 of 2, MacMillan and Co, Limited, London (1914)

- James George Frazer, The Golden Bough: A Study in Magic and Religion, Abridged Edition, The Macmillan Company, New York (1925)

- Clive Hart, Structure and Motif in Finnegans Wake, Northwestern University Press, Evanston, Illinois (1962)

- David Hayman, A First-Draft Version of Finnegans Wake, University of Texas Press, Austin, Texas (1963)

- James Joyce, Finnegans Wake, The Viking Press, New York (1958, 1966)

- James Joyce, James Joyce: The Complete Works, Pynch (editor), Online (2013)

- Roland McHugh, The Sigla of Finnegans Wake, University of Texas Press, Austin, Texas (1976)

- Roland McHugh, Annotations to Finnegans Wake, Third Edition, The Johns Hopkins University Press, Baltimore, Maryland (2006)

- Charles E Pearce, Sims Reeves: Fifty Years of Music in England, Stanley Paul & Co Ltd, London (1924)

- Danis Rose, John O’Hanlon, The Restored Finnegans Wake, Penguin Classics, London (2012)

- Arthur Symons, William Blake, E P Dutton and Company, New York (1907)

- John B Vickery, The Literary Impact of The Golden Bough, Princeton University Press, Princeton, New Jersey (1973)

Image Credits

- James Frazer: Walter Stoneman (photographer), National Portrait Gallery, London, Public Domain

- The Golden Bough: Joseph Mallord William Turner (artist), Tate Britain, London, Public Domain

- The Viconian Cycle: © Tim Finnegan, Fair Use

- Ouroboros: AnonMoos (designer), Public Domain

- John Boyd Dunlop: Anonymous Photograph (1915), Public Domain

- Tim Finnegan’s Fall: John Vernon Lord (artist), Finnegans Wake, The Folio Society, © 2014 John Vernon Lord, Fair Use

- A Traditional Irish Wake: Irish Wake, M Woolf (artist), Harper’s Weekly: A Journal of Civilization, Volume 17, Number 846, 15 March 1873, Page 204, Harper & Brothers, New York (1873), Public Domain

- James S Atherton: Mary Talbot (photographer), Public Domain

- William Blake (12 April 1827): Thomas Phillips (artist), National Portrait Gallery, London, Public Domain

- John B Vickery: © The Family of John B Vickery, Fair Use

- T S Eliot: Ottoline Morrell (photographer), National Portrait Gallery, London, Public Domain

- St Andrew’s Church, Site of the Dublin Thingmote: © The Irish Times, Fair Use

- Première of Felix Mendelssohn’s Elijah (26 August 1846): Anonymous Engraving, The Illustrated London News, 29 August 1846, Page 137, Public Domain

- The Death of Caesar: Vincenzo Camuccini (artist), Galleria Nazionale d’Arte Moderna e Contemporanea, Rome, Public Domain

- Sechselaütenfeuer (The Burning of the Bögg): Postcard, Photochrom Zürich, Zentralbibliothek Zürich, Public Domain

Useful Resources

- William Blake’s Letter to George Cumberland

- Jorn Barger: Robotwisdom

- Joyce Tools

- FWEET

- The James Joyce Scholars’ Collection

- FinnegansWiki

- James Joyce Digital Archive

- Genitalia in Finnegans Wake

- John Gordon’s Finnegans Wake Blog

- James Joyce: Online Notes