Trees & Goats Could Save the World

(An essay on the use of tree fodder in meat goat production)

How does a city boy end up on a Godsend of 150 acres? Moreover, how does that boy, now a man, choose and achieve to farm in one of the most unarable lands of North America, a place where flat land, fair weather, and rich deep soil, is as common as the clean end of a cow patty? The long story is beyond the scope of this article. The short story goes like this; in 2011 Michael and Lindsay Walder started Mahna Farms in Bancroft Ontario, Canada. They raise meat goats. Over the last few years, due to concerns with the genetic modification of conventional feeds, and limited feed sources in the area, Michael has been researching and using an unconventional feed: Tree Fodder.

Using trees to feed livestock is gaining popularity in many parts of the world. At first introduction it comes across as something new but it is actually an ancient practice, as evidenced by the very old Pollards found throughout Europe. Pollarding is a tree pruning technique used to produce copious leafy shoots for fodder that can be harvested on a 3-8 year cyclical rotation. The branches or “shoots” are grown out of reach from grazing animals, but kept accessible enough for farmers to reach safely via ladders or climbing. When one logs onto Google and searches for, “Pollard, or tree fodder”, documents arise which condense this unfamiliar practice into a very becoming notion that, “This Could Work!” Modern scientific studies are proving the nutritional value of various tree leaves, and finding ways to unlock these nutrients making them more accessible to the animal during rumination.

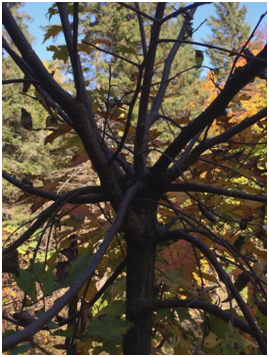

Photo above: This Elm tree was 2” in diameter at 6’, was topped at that height and had all its stems removed in February 2015. The tree was dormant at the time so it had full reserves to start fresh as a Pollard in the spring. The trees need at least three years to recover between harvests. Michael jests, “I figure the trees need one year to say ‘whoa what just happened’, then another year to say ‘ok…I get it…I guess it’s alright”, and then a third year to say, ‘Bang! I get it, and I like it!’ Michael’s trees are on a four year cycle as he feels in the fourth year the trees will be saying, “Ok…we’re bored…let’s get on with another fodder harvest”.

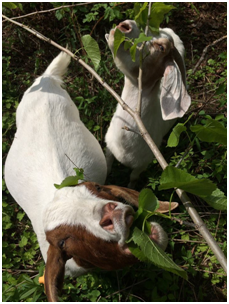

Michael’s foray into using trees to feed goats didn’t start with Google promptings. It started with observing his goats and their cousins, the White-tailed Deer. By following the goats around the land, he quickly learned that they prefer to eat at head height or higher. The goats let him know by their enthusiasm which tree species they preferred, and which ones they did not. Also, by observing what White-Tailed deer were browsing in the area at different times of the year, he noted when and what he should try offering to his goats. This was helpful as the goats’ preferences change throughout the year and so does the digestibility and/or nutrient levels of the various types of fodder. As Michael’s walks with the goats and observation of their behavior continued, serendipitously in the winter of 2014/2015 he was watching a documentary. In it there was a man discussing primitive ways that Europeans used to feed livestock. At one point the man emphatically shook his fists and said, “NEVER, NEVER, NEVER did animals eat grass, we made them eat grass!” He went on to talk about the art of pruning trees into Pollards. It was extremely encouraging information for the direction that Mahna Farms was taking.

One may find that venturing into the use of tree fodder as a feed source is an exhausting effort. Unfortunately, this nearly lost art leaves more questions than answers; such as, how much can the trees produce? How much will the goats need? How can I process fodder to store as winter feed? Michael’s opinion is, “There are so many variables that will affect production levels; such as, time, light, weather, soil fertility, tree species, number of stems/acre, feed conversion genetics of your livestock, and physical capabilities of the staff. Each producer needs to feel his/her way at this point. Collaboration is important, but individual experience is best”.

Before we lose the reader on the concept, here are some of Mahna Farms’ 2015 - 2016 numbers and activities to demonstrate the value of using tree fodder. In 2015, during the kidding/lactation season, aside from grass hay and 1lb of alfalfa pellets/day/dam, the goats (dams and kids) were given access to pasture and forest for 4-5 hours per day. Their feedings were broken into two periods, one in the late morning after the dew had burned off, and the second in the evening before dark. Michael would follow the goats during the forage times, and cut branches for them that were out of their reach. This method of feeding fresh fodder was time consuming and much of the fodder was wasted as the goats trampled it into the ground. Most of the tree fodder being harvested in 2015 was that which was in reach of a 10’ pole pruner so, supply was limited. With less than satisfactory results at weaning, Michael rethought his approach and decided to try confinement feeding for 2016. He figured that with the 4-5 hours he was using to follow the goats around, he could ‘cut and carry’ more fodder to them than they were getting at ‘free ranging’. Accepting 2015 as a learning experience, Michael ate his losses (somewhat literally) and carried on.

After kidding in the spring of 2016, Mahna farms’ goats were put on a ‘cut and carry’ system. In other words, the goats were kept in a ¼ acre enclosure; feed was brought to them, and placed in feeders. Daily, over the course of the lactation period, and up to weaning at 90 days, 32 goats (10 dams, 18 kids, 2 sires, and 2 adolescents) were fed approximately 250-350lbs of fresh tree fodder (spread over 3 feedings), 100lbs of fresh grass/forb cuttings (1 feeding), 30lbs of dry hay (free choice), and 1lb of Alfalfa pellets/dam. The tree fodder was cut in the morning. From bud break in the spring, primarily Populus tremuloides (Trembling Aspen), and Betula papyrifera (White Birch) were fed until the goats started refusing it at the end of June. After that time, the tree fodder was mostly Tilia Americana (Basswood), Fraxinus spp. (Ash), and Ulmus americana (White elm) until leaf fall. Michael is a trained arborist and all the climbing and pruning was done with hand tools (professional climbing gear, ladders, hand/pole pruners, billhooks, & handsaws).

Photo above: Pictured here is an “Angelo B” Italian Billhook. According to Michael the Billhook is the single most important tool in fodder collection. “I couldn’t be without it. If you get one, buy the best one that you can. What you spend on your steel will pay you back 100 fold in edge retention and slashing ability.”

The trees were pruned in a manner to maintain health and promote suckering (i.e. Pollarding). “If you try this at home, as a rule, don’t take more than 30% of the leaves from a tree, and don’t remove a branch that is greater than ¼ of the diameter of the branch from which it is coming from”, says Michael, and adds, “That prescription is more or less the rule to ensuring the health of your tree, but in order to get the vigorous suckering found in Pollards, I’ve found that you might need to push those limits”. In one to two hours, more than enough fodder was obtained to keep up with the three feedings per day. The excess fodder was a ‘bonus’ for Michael that could be stockpiled and fed on rainy days, or used on days when he worked away from the farm and didn’t have time to prune. Beyond that, the excess was dried and stored as “TreeHay” for winter feed. Once the tree fodder chore was done for the day, Michael would then harvest the pasture grasses and forbs using an Austrian Scythe. The total gathering of all the feed (tree/grass/forbs) would take about 3 hours. This left much of the day to carry on with other activities.

Let us digress for a moment and go back to the concept of “TreeHay”, for it is just as important to Michael’s vision for Mahna Farms. He recalls his first attempt at TreeHay for us, “In the spring of 2015, I felled a large Aspen (Populus tremuloides) in the woods. I limbed it, piled the branches in two large mounds about 4’ high, and then purposely, ‘forgot about it’. Two weeks went by, and the fodder had been rained on and dried out about three times. I figured at this stage, it would be desiccated, black, and all around undesirable to goats. I was wrong. When I led the goats to it on one of our walks, they had the lush green of spring all around them, but chose to dive on that pile of TreeHay like is was candy. Each walk, until every accessible leaf was consumed from the two piles, the goats made a beeline for their ‘stash’ every time we went out.” The desirability of the product to his goats, and the forgiveness of TreeHay preparation (compared to grass hay’s demand for 3 days of sun) was a sincere proof of concept for him. From thence he experimented with ways to store TreeHay.

Photo above: Two bales of leaves that Michael made using a homemade manual Box Baler. All stems down to 1/8th of an inch were sheared off of the branch with a billhook, and stuffed into the baler. The goats will eat all the leaves and stems. “Drying in the shade is a must. The sun sucks something out of them, and the leaves start to go brown”, he says. The photo shows the difference between shade dried leaves (on left) and ones that were touched by the sun (on right). Both bales are Aspen. Each bale takes about 5 minutes to make using the Box Baler.

A Box Baler2 worked well but, it was too laborious. The leaves were allowed to dry to the point where they felt like ‘wax paper’ before baling. Depending on the weather, and the time of year, this step could take anywhere from three days to three weeks. Although he never tried Box Baling green fodder, the whole process was too drawn out. Michael needed a faster, systematic routine. Returning to Google again, he found a tool called a “Nunchaku” (two sticks joined on one end, by a chain, or rope). A Nunchaku was commonly used as a threshing tool; however, in certain circles it was also used as a way to bundle up various materials. Michael used a nunchaku to wrap around a pile of fodder. Then the ridged wood arms could be leveraged to compress the bundle tightly while it was being tied off with cordage. He found this bundling or “sheaving” to work better than the bale. The fodder for the sheave could be cut and wrapped the same day, and in far less time. The fodder dried, under cover, in tightly wrapped 10” diameter sheaves with no ill effects.

Another proof of concept came in the form of year over year data collection. Mahna farms is enrolled in the Goat Herd Improvement Program offered for free by Dr. Andries ([email protected]) working out of Kentucky State University. This program enabled Michael to observe a year to year change in his production levels when comparing the 2015 & 2016 feeding styles (i.e. pasturing vs. dry lot). The GHIP summary for 2016 realized an average increase of 5.4lbs at weaning (90days) over the 2015 GHIP summary. He feels that since the 2016 results are only from one year’s numbers, he won’t attribute the increase solely to tree fodder; however, the results are encouraging enough for him to continue on this path.

Although Mahna Farms saw gains in 2016, Michael admits that even 3 hours of collection time is too much to spend on feedings, as he wants to increase his herd tenfold. Considering the number of fodder trees that he has access to on their 150 acres and the excess that was produced daily, he figures if he put in a full day of fodder collection he could potentially feed that many head; however, “There is too much pressure to produce working like that”, he says. What Michael sees in the future for Mahna farms, is to finish fencing the land. He wants to create a rotational pasture system and envisions a savannah type setting where grasses and forbs on the forest floor can be browsed free choice by the goats during the growing season, and the trees can be harvested primarily for TreeHay (winter feed).

If one could envision the immensity of this project, or the massive amount of storage space needed to feed enough TreeHay all winter for 100+ goats they may be right in siding with skepticism. Michael has thought on the problem of storage and came up with a prospect: pelleting the TreeHay. An entry level price for startup pelleting equipment runs about $2500 (U.S). Beaming Michael says, “As soon as I’ve got the funds…I’m getting it! There are studies that speak to the barriers of tree fodder’s total digestible nutrients (eg. Tannins) being broken down by drying, heat, steam and pressure! All 4 of those elements are present in the pelleting process!” Besides being able to unlock nutrients, and store more in less space, you could also add minerals, oils, and/or other types of supplements to the pellet. The one downfall for Michael to the dream of pelleting is that the machines run on fossil fuels or electricity. “I guess there will have to be some give and take there. If you did a carbon foot print between pelleting and the other options (growing conventional hay/grains), or an ecological study that focuses on the impact to the environment, I’ll bet the ‘earth-friendlier’ option would still be pelleting.” he said. Trees are sustainable, rich, flexible, symbiotic with other life forms and a time-honored way of feeding livestock. This practice is green, and it is “NOW”!

In the meantime, we’ll leave you with this; the local Priest came for a visit to Mahna Farms. He is from Africa. When Michael told him what he was doing with the goats (feeding them tree fodder), the Priest said, “Of course”, as if it was not a new concept. He continued, “In Africa everyone feeds tree leaves to goats, I never saw a goat eat grass until I came to Canada!”

Mahna Farms contact: [email protected], https://www.facebook.com/mahnafarmsboergoats/

Box baler plans can be found at: http://www.caringforgodsacre.org.uk/images/uploads/fact_sheets/Hand%20Hay%20Baler%20Plans.pdf

(Photo above): “Ok Michael, we know its winter, there are no leaves up there, but there are twigs…” Yet, that’s another story.)

Cool! I follow you.

Downvoting a post can decrease pending rewards and make it less visible. Common reasons:

Submit

Congratulations @wailing-4justice! You received a personal award!

You can view your badges on your Steem Board and compare to others on the Steem Ranking

Vote for @Steemitboard as a witness to get one more award and increased upvotes!

Downvoting a post can decrease pending rewards and make it less visible. Common reasons:

Submit