Products made possible through gene-editing have landed on grocery shelves. Whether they’ll stay there is up to shoppers wary of technological tinkering.

Food companies are now required to label GMOs in Vermont, and debate is raging over a federal standard. But so far, regulators at the U.S. Department of Agriculture have taken a pass on overseeing gene-edited crops. They say cutting DNA from a plant is not the same as adding genes from another organism. So corn injected with outside DNA is classified a genetically modified organism, but canola that can tolerate herbicide because scientists removed a gene is not.

Industry giants like Monsanto Co., DuPont and Dow Chemical Co. have stepped through the regulatory void. They’ve struck licensing deals with smaller companies for gene-editing technology. U.S. farmers harvested 8,000 acres (3,237 hectares) last year of gene-edited canola processed into cooking oil marketed as non-GMO. Looming are U.S. consumers who’ve rejected GMO products despite a preponderance of evidence that they’re safe to grow and eat.

Consumer Feeling

“There’s a feeling among consumers that they want their food as close as possible to what nature intended,” said Carl Jorgenson, director of wellness strategy at Daymon Worldwide, a retail marketing firm. “There’s an overall distrust of Big Food and Big Science.”

Farmers and scientists have manipulated crops for thousands of years. Gene-editing is what proponents call a more precise version of mutation breeding that’s been used since the mid-1900s. Commercial varieties of edibles, including wheat, barley, rice and grapefruit, were created by mutating DNA with chemicals or radiation.

With GMOs, there’s suspicion among consumers. U.S. food companies spent millions fighting labeling requirements, fueling theories that GMOs are unhealthy. And there’s a sense that the benefits of genetically engineered crops have gone mainly to farmers and big agricultural companies that supply seeds and pesticides and not to consumers.

Labeling Laws Are New Front in Battle Over GMO Foods: QuickTake

Doug Gurian-Sherman, director of sustainable agriculture at the Center for Food Safety, said today’s conversations about gene-editing remind him of GMOs in the 1990s -- the rhetoric is lofty and promises abound about healthier food and drought tolerance.

“This is largely unproven,” Gurian-Sherman said. “There’s a proclivity to believe we can develop new, useful technology that will answer tough problems.”

Edited Soybeans

Calyxt, a Minnesota-based subsidiary of the French bio-pharma company Cellectis, has developed genetically edited soybeans that produce oil able to withstand high cooking heat without producing trans fat. Crops are growing in the U.S. and Argentina and could be on the market as soon as 2018. Calyxt is also working on low-gluten wheat and potatoes that make healthier french fries and chips.

“If that mom shopping Kroger sees a bag of potato chips that has less neurotoxins, they may see a value there,” said Daniel Voytas, chief science officer at Calyxt. “We’re very much focused on the consumer.”

There are various forms of gene-editing technology, but the most well-known is Crispr, a platform embroiled in a fight over patents that could be worth billions of dollars. The USDA recently said it wouldn’t regulate Crispr mushrooms that resist browning with age.

Crispr, the Tool Giving DNA Editing Promise and Peril: QuickTake

Gene-editing has applications beyond food. Bill Gates has said the technology can eradicate malaria, and it’s being used to attack other debilitating diseases. Scientists have also used gene-editing to create hornless dairy cows, a DNA modification that eliminates the need to painfully remove them.

Crops are on the forefront of gene-editing because plant DNA is the easiest to manipulate.

San Diego-based Cibus changed one letter from canola’s DNA to create the new variant. Farmers in North Dakota and Montana planted about 20,000 acres of sulfonylurea-resistant canola this year, and Cargill Inc. is making it into cooking oil. Developing a new trait takes just five years with gene-editing, compared with seven to nine years with traditional breeding techniques and as long as 15 years with transgenic methods, which have been used to create the current generation of GMOs.

DuPont recently established a plant-breeding platform based on Crispr that’s focused on corn. The company may expand it to soybeans, rice, wheat and canola, said Neal Gutterson, vice president of research and development at DuPont’s Pioneer seed unit.

Dow, which has licensed gene-editing tools, is focusing on corn and soybeans that repel insects without chemical pesticides and tolerate herbicides for easier weed control.

Monsanto, known for its genetically modified seeds, has also gotten into the game, making its first public foray into gene-editing by striking deals with a pair of companies working in the field.

!( )

)

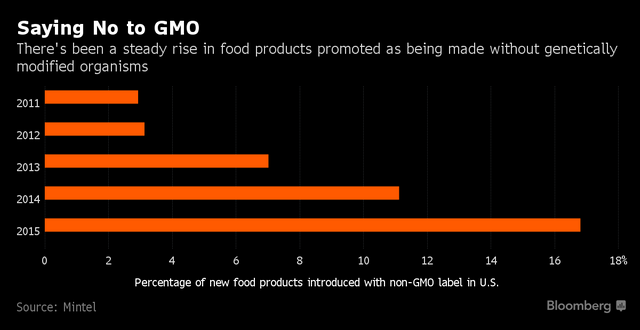

Despite studies saying there’s no risk to eating GMO food, a growing number of U.S. consumers are avoiding them. Nearly 17 percent of new food products introduced in the U.S. last year carried a non-GMO label, up from less than 3 percent in 2011, according to Mintel, a market research firm. And 52 percent of respondents to a Mintel survey said they seek out non-GMO products. Even if Congress passes a bill requiring national GMO labeling, it won’t apply to gene-edited crops as regulations now stand. The question is if that will last.

In Europe, regulators have not yet decided how to deal with gene-editing. Canadian officials, meanwhile, have said that food created with technology like Crispr will be regulated as “novel” products, like traditional GMOs.

Last year, President Barack Obama ordered a review of the way biotechnology in food is regulated. Greg Jaffe, the director of biotechnology at the Center for Science in the Public Interest, said regulators should address the void in oversight.

“The system is broken,” Jaffe said. “At the very least, consumers deserve a decision based on science and safety.”