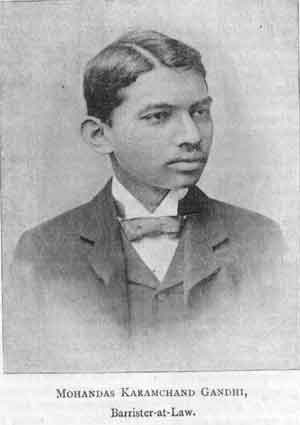

On May 24, 1893, Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi arrived in South Africa. It was the third continent the 23-year-old barrister had set foot on. During his first two weeks, he was greeted with violent racism, reluctant compassion, and loving welcome. These experiences could have sent the young man down a path of racial hatred or religious extremism. Instead, they forged a principled but imperfect leader who would inspire millions across the globe with his messages of truth and nonviolence. As Nelson Mandela said of Gandhi’s years there, “You gave us a lawyer, we gave you a Mahatma [Great Soul].”

Five years earlier, at the age of 18, Gandhi had sailed to London from his native India, anxious to begin his studies of the law. His autobiography, the main source of information about his early life, makes no mention of discrimination during his years there. After graduation, he returned to India to start a legal career, only to discover that his formal schooling was not the boon that his family had expected. It took years to establish a reputation in Bombay's competitive marketplace, and Gandhi's ethical objections to the system of bribes that greased the system hindered any real progress.

The year 1893 brought a different opportunity. Dada Abdulla, a wealthy Muslim trader in South Africa, contacted Gandhi’s older brother, Laxmidas, seeking outside council for a complicated lawsuit. Fluent in English and Gujarati, and formally trained in London, Gandhi was uniquely qualified. Accepting the offer, he said goodbye to his wife and two sons, consoling her with the thought, “We are bound to meet again in a year.”

The specter of racism first appeared when he tried to buy a first-class ticket on the ship to Africa. Gandhi was told that only deck passage was available for him, which he found suspicious. He set off to find the captain and learned the real reason: a large party of VIPs had bought up all the first-class compartments. Gandhi's persistence appealed to the captain, who offered him the berth in his own cabin that was usually reserved for crew members, and the ship departed from Bombay on April 24.

This voyage was one of the rare times in his life that Gandhi was able to slow down and relax, his years in jail notwithstanding. There were no urgent demands on his time, nothing to prepare for. He became fast friends with the captain over a chessboard. The captain, an enthusiastic novice at the game, was pleased to teach Gandhi, and was doubly pleased that Gandhi continued to play despite losing every time. The same rules applied to both white and black pieces, with each color enjoying equal freedom of movement. South Africa would bring a different story.

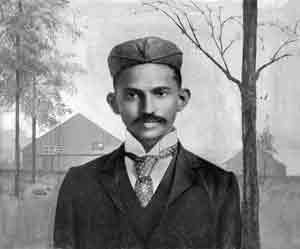

Dada Abdulla met Gandhi when he docked in Durban on May 24. Although he was one of the richest traders in the region, Gandhi quickly “observed that the Indians were not held in much respect” in South Africa. Gandhi shadowed the Muslim man for several days, bedecked in an expensive European-style frock coat, striped pants, and turban, trying to make sense of the foreign land.

It was on the second day that the pair attended Durban's local court. The magistrate looked several times at Gandhi, trying to resolve the paradox of South Africa’s first Indian lawyer. Finally, he ordered Gandhi to remove his head covering in the courtroom. The young man looked to the turbaned Abdulla, unsure of why he was being singled out. Rather than dispute the matter, Gandhi rose and walked out of the room, despite his conviction that he had done nothing wrong.

That afternoon, Abdulla described the categories of Indians in South Africa, which fell largely along religious lines. Muslims such as himself wore turbans and were referred to as “Arabs.” Christians wore English clothes and hats, and were generally employed as waiters. Parsi clerks called themselves “Persians.” Hindus made up the vast majority of the Indian labor pool, generally having arrived as indentured laborers to work the fields. They were called “coolies.”

More embarrassment followed the next day. The Natal Advertiser described the courtroom incident in a paragraph titled “An Unwelcome Visitor.” Gandhi promptly wrote to the editor, explaining that his actions had been respectful, in accordance with Indian court customs. The mild controversy in the paper established Gandhi as the “coolie barrister.”

Determined to demonstrate his worth to Abdulla, Gandhi familiarized himself with the details of the case that had brought him from India. He had never learned accounting, but a book on the subject and conversations with Abdulla’s clerk brought clarity. His quick study impressed Abdulla, and by midweek Gandhi was preparing to travel north to Pretoria to represent his employer's interests in the case.

In the late afternoon of May 31, Gandhi boarded the train for the first stage of the 500-mile journey. He’d traveled by train in India and England, often utilizing third class in the interests of economy, but now he was a world-traveling barrister representing a wealthy client. At the age of 23, he made himself comfortable in the first-class compartment he felt he deserved.

The sun had set by the time the train pulled into Pietermaritzburg station, and a railroad employee brought around bedding to each compartment for the night’s journey. Gandhi, displaying his usual frugality, declined to pay the additional five shillings for it. The employee left without questioning the irregularity, but a white passenger soon arrived and observed an irregularity of his own; Gandhi was a “coloured” man. Railroad officials crowded into the compartment and demanded that Gandhi move back to third class. When he declined, they threatened to call a constable and have him thrown out.

“Yes, you may,” Gandhi responded. “I refuse to get out voluntarily.”

What must he have thought as he waited for the constable to arrive? He surely recalled the shame he felt from his voluntary exit from the courtroom the previous week. This time, he was determined not to waive his rights on an unjust demand. Clutching his first-class ticket, he sat stoically under watchful eyes.

The constable arrived. Ignoring Gandhi's explanation, he pulled the “coolie barrister” from the compartment and forced him out onto the railroad platform. The wintry night air bit into Gandhi as he stood there, alone in a strange country, far from anyone he knew. Again, he was told to take his first-class ticket back to the third-class compartment.

Gandhi refused. The train steamed on, abandoning him.

It was his first act of civil disobedience. Unlike in the courtroom in Durban, Gandhi stood up to capricious authority. His compliance with an unjust demand had been compelled by force. He had maintained the moral high ground, but now came voluntary suffering. In later decades, millions would follow the news of his incarcerations and fasts, but at the train station, he was alone. Gandhi spent the night in the dark, unheated waiting room, pondering what to do next. He declined to ask permission to retrieve his overcoat from his luggage, preferring shivering to supplication.

What now? In his autobiography, he concludes:

“It would be cowardice to run back to India without fulfilling my obligation. The hardship to which I was subjected was superficial – only a symptom of the deep disease of colour prejudice. I should try, if possible, to root out the disease and suffer hardships in the process. Redress for wrongs I should seek only to the extent that would be necessary for the removal of the colour prejudice.”

In the morning, Gandhi sent a long telegram of protest to the railroad company and notified his employer as well. Back in Durban, Dada Abdulla had insisted that Gandhi make a reservation for bedding on the train, but Gandhi refused with the same obstinacy that he would later demonstrate to India’s British rulers. If Abdulla's response included the phrase, “I told you so,” there is no record of it. When the evening train arrived, Gandhi boarded and took his rightful place in first class, but not without making a concession of his own. He spent five shillings and purchased bedding for the night.

Gandhi slept as the train steamed north. Whatever peace he felt would be shattered by violence the following day.

Part 2 can be read here.

Sources:

Photos from Wikimedia Commons and Gandhi (1982).

Gandhi Before India (Guha, 2014)

An Autobiography: The Story of My Experiments with Truth (Gandhi, 1927)

The Life and Death of Mahatma Gandhi (Payne, 1969)