(Spoilers certainly follow.)

Utah rode a roller coaster for half a year in a battle over gay marriage, with advocates and the LDS church fiercely on different sides. The struggle in the form of law was the case Kitchen v. Herbert, and Holly Tuckett and Kendall Wilcox have told the story in “Church & State,” showing in Salt Lake City July 13-20 at Broadway Centre Cinemas.

Audiences thinking that they know the tale may be surprised, however, as Tuckett and Wilcox are offering a production rich in detail.

Tuckett did not return a request for comment.

Among the highlights:

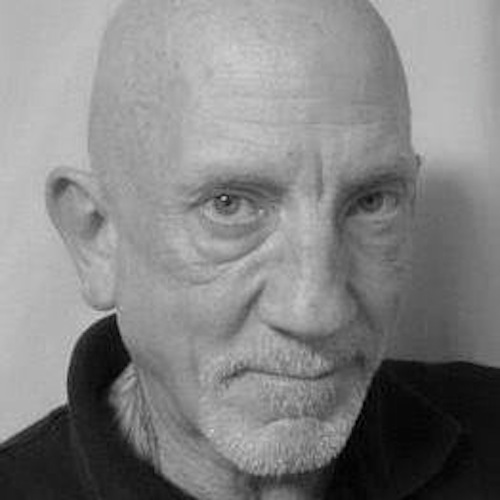

Mark Lawrence, the man who brought about the legal case

Mark Lawrence (Mark Lawrence via The Village Square)

Maybe he just got tired of hearing Cherilyn Eagar sing at a traditional marriage rally, but when you see an adversary, perhaps it’s generally not typical to say “I think we should down and see if we can catch him.”

Yet that’s exactly what Mark Lawrence did upon learning that National Organization for Marriage co-founder Brian Brown was in the Utah State Capitol.

After arguing with him, Lawrence says “That is a lifelong ambition and I finally met it.”

Lawrence’s mother tells Lawrence that it was a “shock” to his parents when Lawrence told them he is gay.

“But I do not understand how parents can kick a child out of their home when they find they they’re homosexual,” she adds.

Lawrence lived in San Francisco but did not participate in social action for gay causes. He feels bad about that, so he sought to make up for it by seeking the end of Utah’s Amendment 3, which prohibited gay marriages and was struck down.

Then Lawrence survived lung cancer.

“I’ve got this second chance now; let’s do something,” Lawrence remembers thinking.

Lawrence did go to the American Civil Liberties Union to fight Amendment 3, but the ACLU told him “you can’t possibly be serious,” Lawrence said. He proceeded to email several law firms in the state.

Steve Urquhart’s advocacy against the Mormon church

Steve Urquhart (Scott Sommerdorf | The Salt Lake Tribune)

Urquhart was a Republican lawmaker for 16 years before resigning and taking a global ambassador position at the University of Utah. In the film, he says that words are whispered into the ears of Republican leadership and then bills are just passed quickly.

“Nothing’s about to happen at the Capitol that the church doesn’t 100 percent endorse,” Urquhart says. “It absolutely will get its way on LGBT issues; on marriage issues.”

Urquhart also says “It’s tough to understand the church’s motivations unless you’ve been Mormon or maybe Scientologist, one of these all-consuming, all-in religions.”

Urquhart also says that you could say that the United States federal government’s threat to shut down the church’s temples if they didn’t end polygamy is the reason for Mormons’ “persecution complex,” but “it comes down to a doctrine of good and evil.”

Peggy Tomsic & Jim Magleby: the hired guns

Peggy Tomsic, attorney (AP Photo/Rick Bowmer)

Magleby and Tomsic are part of the law firm Magleby Cataxinos & Greenwood. Magleby returned an email from Lawrence. Tomsic says she had “respect” for Lawrence since he “was not involved in any organization nationally or locally that had any power.”

Instead, Lawrence “had just decided on his own he was gonna do this,” Tomsic points out. “And I thought ‘you know what, that takes a lot of hootspa.’”

Tomsic believed in Lawrence even though Lawrence had “no connections,” she says. But she thought “I don’t care” because fighting Amendment 3 was “the right thing to do,” Tomsic adds.

Tomsic herself is lesbian. When she met her wife, Cindy, her pride was dissolved, Tomsic says. She also adopted a boy whose grandmother asked that he stay with her.

Tomsic found the fight to be personal because “if something happened with Cindy, I had no rights; none,” she says.

‘The church’

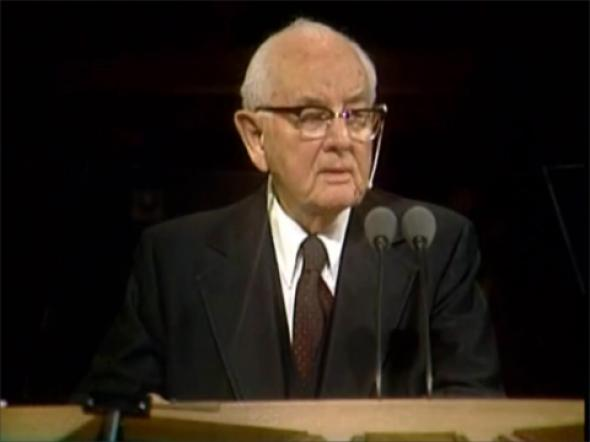

Church history figures into the film, from its origins to the church ending polygamy to gain statehood. It later features remarks from church prophet Spencer Kimball and Mormon apostle Boyd Packer.

“To the great Moses, these perversions (homosexuality) were an abomination and a defilement worthy of death,” Kimball says in a clip.

Mormon prophet Spencer Kimball (LDS.org)

Packer gave a speech in which he praised a missionary for assaulting his companion when his companion made a sexual advance.

“My response was well, thanks; somebody had to do it … and it wouldn’t be well for a general authority to solve a problem in that way,” Packer says in a featured clip. “Now I’m not recommending that course to you, my young friends, but I’m not omitting it.”

Kimball and Packer both spoke in settings and capacities believers meant they were speaking for God.

Taylor Petrey, a professor at Kalamazoo College, says that the Hawaii State Supreme Court’s finding of the state’s refusal to grant same-sex couples marriage licenses to be discriminatory set off “alarm bells in Salt Lake City.”

“(The church) starts to organize politically,” Petrey says.

The church created a document called “The Family: A Proclamation to the World,” which outlines the church’s definition of family structure. The document “became central to Mormon identity really quickly,” Petrey adds.

“It’s really important to understand the importance of this document in Mormon teaching,” Petrey says, saying that the church was “genius” to not have the proclamation mention homosexuality “at all.”

Legislative efforts took place between then and the creation of Amendment 3, journalist Jennifer Dobner remarks.

The political & legal battle in Utah

Tomsic says that she never thought that she could argue that the United States Constitution doesn’t allow for the prohibition of gay marriage, let alone that such an effort would happen in her lifetime.

Lawrence says that in arguments before Judge Robert J. Shelby, it was “not possible” for attorneys for the state of Utah to make a secular argument for traditional marriage.

Judge Robert Shelby (The Salt Lake Tribune)

Magleby points out that Shelby asked Tomsic if he would be the first to rule on the type of gay marriage determination like an Amendment 3 decision. Tomsic tells him yes – and “congratulations,” to laughs from folks in the courtroom, Magelby says.

Shelby’s issuance of a decision on Dec. 20, 2013, was not expected, Lawrence says.

“To file a case in March and have a decision by Dec. 20 of the same year, it’s never happened in my 31 years of practice,” Tomsic says.

That night, hundreds, if not thousands, of gay couples got legally married, Magleby says. Laurie Wood, one of the plaintiffs in the legal case called Kitchen v. Herbert, said that she “got it” after she became Kody Partridge’s wife the night of the 20th.

Tomsic called Cindy to go get married, but Cindy said that she was a doctor and couldn’t leave patients.

Tomsic’s response?

The patients can join them and be witnesses.

Shelby got Tomsic and a state lawyer on the line, with Shelby asking the state attorney to tell him when he is going to file a motion for a stay and he would immediately hold a hearing.

The attorney's response?

“I don’t know what we are going to do,” Tomsic reports.

The state “missed the movement and took for granted that their worldview was the worldview of everyone within the confines of the state,” says Kate Kendall, the former director of the Center for Lesbian Rights. “And because there is so little separation between church and state in Utah, I’m sure that officials in the attorney general’s office not only believed they were right, but they just believed everyone else would think they are right.”

Also on Dec. 20, 2013, KSL, a television station in Salt Lake City, called every county in the state and five counties were not issuing licenses: Box Elder, Cache, Juab, Piute, San Juan, Utah. Delaying were Sanpete and Sevier, reported Sandra Yi.

An event was held by a right-wing group in what appears to be a Mormon chapel, with a woman singing a Mormon hymn outside, her voice trembling. In the background is a Ron Paul for President sticker, though Paul’s ability to ensure a speaking spot at the 2012 Republican National Convention had ended nearly a year-and-a-half earlier.

Lawrence says at a celebration on the 20th that Shelby had a “new title.”

“He is an activist judge,” Lawrence says. But then he adds, “what is an activist judge? Apparently, an activist judge is a judge who understands the constitution of the United States.”

Then, the Supreme Court grants Utah a stay. Amy Goodman of Democracy Now reported that 30 states who had same-sex marriage ban could be impacted if Utah’s ban is overturned.

Division among gay marriage advocates

Lawrence got upset at national organizations who wanted to take over the case. They told him “this is too big for you,” says Lawrence, remarking that national gay rights organizations are “professional homosexuals” making six-figure incomes.

“The pushback was phone calls saying ‘you are a little law firm in the backwater of the nation,’” Tomsic says, adding with emphasis that people were “pissed.”

“A case from Utah was not on anybody’s agenda,” Kendall says.

Kate Kendall, former National Center for Lesbian Rights executive director (NCLR)

Tomsic reached out to Kendall’s NCLR and Lawrence got upset that he saw the story of Derek Kitchen and Moudi Sbeity, other plaintiffs in the case, on the NCLR website. (Kitchen says he wanted to get involved, initially, after there were attorneys involved beyond the “kink in the chain” in Lawrence.) Lawrence also stopped being involved in meetings with the attorneys and plaintiffs.

Sbeity got coverage on the news for calling for civility between sides throughout the public over the issue.

Tomsic says that “(Lawrence) had the warrior mentality and it wasn’t the right time.” Lawrence was then no longer part of the same-sex marriage advocacy team.

The battle goes to the Rockies' east slope

The stay granted, the Tenth Circuit Court of Appeals in Denver was where the case would again be considered. The church hired Gene Schaerr, who said that his Mormonism was his reason to fight gay marriage, which Dobner discusses.

Gene Schaerr (Gene Schaerr)

Urquhart says that additionally, Schaerr met with the Utah Senate and said that they were “forbidden to run any legislation that might touch in the LGBT community and for the Utah legislature to shut its doors.”

“I said I felt he wasn’t representing the state,” Urquhart adds.

Tomsic took issue with the state’s child-centered argument when the state had stopped adoptions.

“If they cared about the kids, they would care about providing as much security, stability and support as they can,” Tomsic says.

Tomsic also remarks that “If you read the state’s brief, it is really an emotional plea based on arguments that are not real or supported by social science and ignore constitutional tenants.”

In Denver, Schaerr cited “authority” granted by the Constitution. Tomsic cited the 14th Amendment of the Constitution.

“These laws are not the types of laws that the constitution will permit,” she also says. “The constitution does not allow for classes between its citizens.”

Former KSL reporter Rich Piatt asks Reyes outside the Denver courtroom what he thought about the hearings. Reyes says that he thinks both sides “acquitted” themselves well. Before the hearing, Reyes tells Kitchen and Sbeity he didn’t want to “hurt” them, Kitchen says.

“I did use the phrase ‘it’s not personal,’” Reyes tells KSL, then next says: “Obviously, it’s very personal to everybody, but I was saying that enforcement of the law was not intended to single out any particular family … I was trying to put myself in their shoes.”

Kitchen doesn’t seem to appreciate Reyes’ claims to Kitchen and his husband.

“I realized he was blatantly lying,” Kitchen says, remarking that if Reyes did care about him and Sbiety, he would not be trying to prevent them from marrying each other.

Wood asks “What else was it?” in reference to Reyes’ efforts to hurt them.

The court upheld Shelby’s ruling on June 25, 2014.

The aftermath

Tomsic claims that Shelby’s decision was the “domino” for same-sex marriage to be legalized nationally by the Supreme Court since Shelby’s court “was the first federal court to declare that a start could not ban marriage equality.”

“It really sank in” for Tomsic when she adopted a child.

“I was a mess,” she says. “I cried; I couldn’t get my voice to quit wavering all over the place."

Near film’s end, Lawrence says that the team he could no longer be a part of was “almost at one point like a little family.”

“Now, we’re enemies,” he adds.

Then he claims that he doesn’t think he would do a same-sex marriage initiative over again.

At the film’s very end, the audience learns that the Supreme Court made its historic decision in June 2015; that the church issued a policy against gays and their children five months later; and that the church declined multiple requests from the filmmakers for an interview.