Women make up an increasingly large contingent of the incarcerated population in the United States. While many studies have examined the health issues and needs among incarcerated women using small or local samples, little research has been conducted that is nationally representative of the health of incarcerated women across different types of correctional facilities. This report uses nationally representative survey data to examine the prevalences of different health conditions affecting the wellbeing of incarcerated women in jails, state prisons, and federal prisons. It is concluded that the majority of incarcerated women have experienced mental health issues within their lifetimes, and that there is a great need for health interventions for both physical and mental health of women in jails, who are much less likely to have received sufficient treatment or examination of any persisting health issues while incarcerated.

Background

Incarcerated populations show markedly different health trends than their non-incarcerated counterparts. As assessed using the 2002 nationwide Survey of Inmates in Local Jails (SILJ) as well as the 2004 Surveys of Inmates in State and Federal Correctional Facilities (SISCF/SIFCF), the prevalence of health issues in the national incarcerated population of both men and women was compared to the non-institutionalized population to show that incarcerated people are more likely to experience hypertension, asthma, arthritis, cervical cancer, and hepatitis than the general population (Binswanger et al., 2009).

While the majority of incarcerated individuals are men (Glaze, 2010), the amount of women joining the correctional population is growing. Between 2000 and 2008, the number of women incarcerated in state and federal prisons increased by 21.6%, while the amount of men in similar facilities increased by 15.6% during the same time period (Guerino et al., 2010). In jails, the population of incarcerated women grew by 0.5% from 2009 to 2011, while the amount of men in jails decreased by 0.5% (Minton, 2012). While there were 51,300 women in jails in 1996, by 2011 this population had risen by around 45%, to total over 93,000 women (Minton, 2012).

Research on the health of incarcerated women finds that that limited access to medical care is likely prevalent and detrimental to health in both maximum-security women’s prisons (Harner & Riley, 2013) and jails (Rose e.t al, 2014). Previous analysis of the 2002 SILJ indicates that that women incarcerated in jails have higher prevalences of all medical and psychiatric conditions as well as drug dependence excluding alcoholism (Binswanger et al., 2010). Furthermore, it is know that there are gender disparities experienced with regard to women in jail, who are more likely to experience poor health outcomes due to HIV contraction than their male counterparts (Meyer et al., 2010).

Access to reproductive healthcare for incarcerated women is often lacking (Mignon, 2016). A study of 725 women in a midwestern urban jail suggests that there is a strong need for social work interventions to begin at jail intake to initiate trauma counseling and preventatively address issues surrounding homelessness, substance abuse, and mental illness (Fedock et al., 2013). While abortion provision is often necessarily to ensure proper healthcare for incarcerated women, this service not always available (Sufrin et al., 2009). While the health issues and needs of incarcerated women have been examined in many small-scale studies, a profile of the health of incarcerated women that examines and discusses the areas in greatest need of health intervention has not yet been created.

Materials and Methods

This paper examines federal data from three different surveys that were given to incarcerated populations: the Survey of Inmates in Local Jails (SILJ), Survey of Inmates in State Correctional Facilities (SISCF), and the Survey of Inmates in Federal Correctional Facilities (SIFCF). These surveys, collected by the Bureau of Justice Statistics, are all incredibly similar, and many topics are covered through similar or identical questions. Containing questions on different topics such as race, socioeconomic status, criminal history, criminal offense information, and health, these surveys are valuable resources for the study of incarcerated populations. These surveys all have large, nationally representative samples, which is rare for otherwise restricted research on incarcerated persons.

For this paper, data on the health of incarcerated women will be examined using all three surveys (nSILJ = 1,993, nSISCF = 2,930, and nSIFCF = 958). Data from local jails (SILJ) is representative of the year 2002, while data from state and federal prisons (SISCF and SIFCF, respectively) is representative of the year 2004. As the amount of incarcerated women has grown considerably in recent decades, the conclusions of this paper are only suggestive of the state of the health of incarcerated women in present day. This is a limitation not only for this paper, but for the knowledge of incarcerated populations in general, as this is the largest available dataset that is available to inform policies that might affect these populations.

This dataset was examined for the prevalence of persistent physical health issues, which are issues reported as presently affecting one’s health. These issues include cancer, hypertension, diabetes, kidney issues, asthma, hepatitis, paralysis, brain injury (including stroke), heart issues, arthritis and rheumatism, cirrhosis, sexually transmitted diseases (STDs), dental issues, accidental injury while incarcerated, intentional injury while incarcerated, and influenza. After identifying the prevalence of these issues among women in jails, federal prisons, and state prisons, the examination rates for those currently experiencing each health issue were analyzed. These rates were used to indicate which specific health issues tend to be untreated or undertreated.

The prevalence of mental health diagnoses were also examined in these populations. Mental health issues include lifetime prevalence of anxiety disorders, depressive disorders, schizophrenia and psychotic disorders, personality disorders, post traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), bipolar affective disorder, and other mental health disorders. While the numbers examined include lifetime prevalence, the recency of diagnosis was examined as well.

Furthermore, while not classified as psychiatrically diagnosed disorders in this survey, lifetime prevalence of one or more suicide attempts are examined, as is the prevalence of present drug dependence. Rates of prescription of mental health medication before and during incarceration are examined, as are rates of mental health treatment (as defined by the presence of mental health counseling or examination while incarcerated). In addition, the prevalence of the feeling of mental health impairing daily functions is examined. All analysis was done in the programming language R (R Core Team, 2017), and all programs used to analyze this survey data are on GitHub (Finkel, 2017).

Results

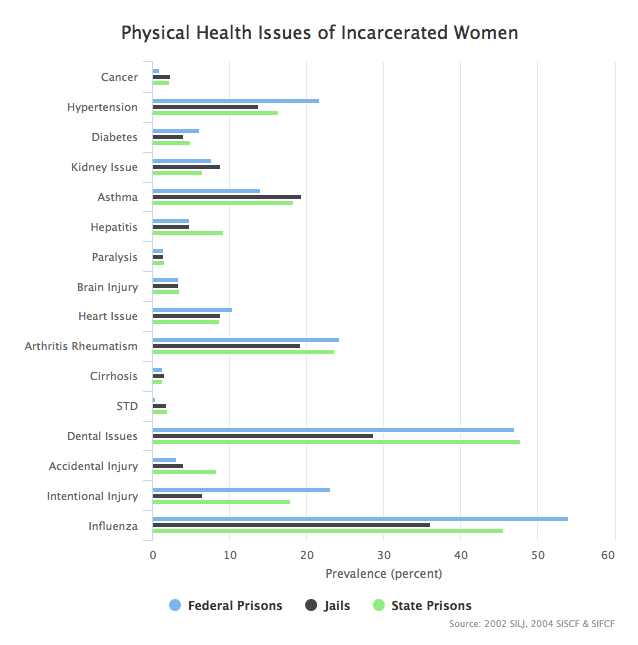

The prevalences of present physical health issues among incarcerated women are shown in Figure 1 (also Table 1 in the below section). The two most prevalent issues women have experienced while incarcerated are dental issues and influenza. Notably the majority of women in federal prisons (54.1%) report experiencing influenza while incarcerated. While 28.7% of women in jails reported experiencing dental problems while incarcerated, 47.1% of women in federal prisons and 47.8% of women in state prisons reported this.

Figure 1. The prevalence of health issues among incarcerated women.

Hypertension, asthma, and arthritis and rheumatism are also among the more prevalent conditions. Relative to federal and state prisons, both accidental and intentional injuries are much less prevalent in jails. Relative to federal prisons and jails, which both experience 4.8% prevalence of hepatitis, state prisons experience a 9.3% prevalence of the condition. However, most rates are ostensibly similar.

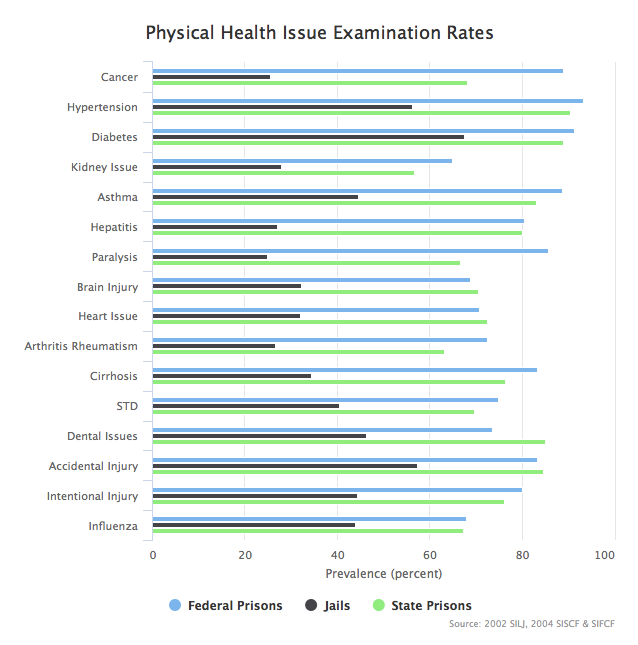

Figure 2. The examination rates among women experiencing persisting health issues.

Figure 2 (see Table 2 below as well) documents what percentage of women experiencing a particular physical health issue while incarcerated have been examined for it. There is a clear trend among every single physical health issue that women in jails always less likely to have experienced medical attention for any particular persistent health issue. For example, while at least 80% of women in federal and state prisons who have hepatitis have received medical attention with regard to the condition, just over 27% of women in jails have received similar treatment.

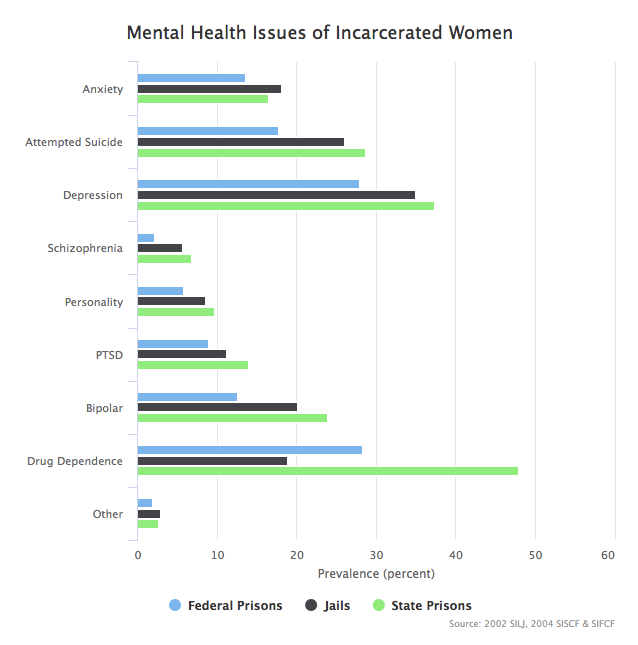

Figure 3. The prevalence of mental health issues among incarcerated women.

Figures 3 and 4 (represented by Tables 3 and 4 below as well) indicate that the majority of incarcerated women have either been diagnosed with psychiatric disorders or attempted suicide within their lifetimes, or are currently drug dependent. While 52.7% and 58.1% of women in federal prisons and jails report this, 72.4% of inmates in state prisons. This difference may be driven by the high prevalence of drug dependency among women in state prisons (47.9%) as compared with jails and federal prisons (18.9% and 28.3%, respectively).

Across all populations, depression is the most common mental health issue, and it is experienced by over a third of women in jails and state prisons, and over a quarter of women in federal prisons. Among women with a lifetime prevalence of any psychiatric disorder diagnoses, the majority of diagnoses took place within 2 years prior to survey administration across all populations (Table 5). Other mental health issues with high lifetime prevalences include bipolar disorder, anxiety disorders, and attempted suicide.

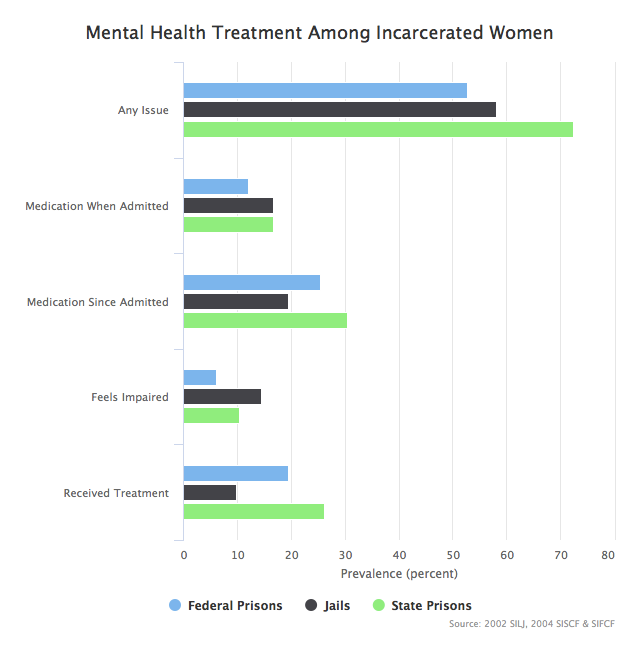

Figure 4. Additional information of the mental health of incarcerated women.

| Source | Time of Mental Health Diagnosis | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| < 6 months | 6 months - 1 year | 1 - 2 years | 2+ years | |

| Federal Prisons | 27.25 | 20.96 | 20.36 | 31.44 |

| State Prisons | 30.54 | 14.22 | 15.67 | 39.57 |

| State Prisons | 32.85 | 18.34 | 15.07 | 33.75 |

Table 5. Recency of psychiatric diagnosis among incarcerated women with psychiatric disorders.

Figure 4 (and Table 4 below) shows that after admittance to correctional facilities, all groups are more likely to be currently taking psychiatric medication, although this change is smaller in jails. In federal and state prisons, there are more women who have received treatment than report feeling impaired by poor mental health on a daily basis. Conversely, women in jails are more likely to feel impaired by mental health and less likely to have received treatment while incarcerated.

Discussion

This report demonstrates the high prevalence of mental health issues across different populations of incarcerated women, and highlights the lack of care received by women in jail in particular. While women incarcerated in jails share similar prevalences of physical health issues to women incarcerated in state and federal prisons, they are drastically less likely to have been examined for these issues. The same is true for the treatment of mental health issues in jails. Notably, the majority of incarcerated women have experienced in their lives. There are high instances of several physical health issues among incarcerated women as well, such as hypertension and dental issues.

There are several limitations of both the surveys used in data collection and what can be inferred from them. The surveys used consist of self-reporting question, and the health-related questions are not necessarily reflective of an individual's medical history. Furthermore, while women have a specific profile of health needs that men do not, such as reproductive health needs, the survey was largely designed to be unisex and does not contain questions that ask whether or not an incarcerated woman has adequate access to hygiene products, prenatal care in pregnancy, or any specific routine preventative examination. Another large limitation that potentially reduces current applicability of the data is the age of the information: jail data is from 2002, while state and federal prison data is from 2004. While the SISCF was most recently conducted in 2016, the data is not yet available. It is also noteworthy that error rates were not calculated in this report, and the levels of certainty for each rate estimate is not given.

Given these limitations, these surveys do contain a wealth of data on health due to their national representativity and large sample sizes. The analysis of health data in this report may be useful to inform health interventions and to assess where resources are most needed. In particular, there is a need for health care on every type of health issue, both mental and physical, in women’s jails. High prevalence of mental health issues also suggest a need for interventional health services in all incarcerated populations, especially jails.

Tables

| Source | Physical Health Issue Prevalence (%) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cancer | Hypertension | Diabetes | Kidney Issue | Asthma | Hepatitis | Paralysis | Brain Injury | |

| Federal Prisons | 0.94 | 21.71 | 6.05 | 7.72 | 13.99 | 4.80 | 1.46 | 3.34 |

| State Prisons | 2.25 | 16.31 | 4.98 | 6.55 | 18.36 | 9.28 | 1.54 | 3.48 |

| Jails | 2.36 | 13.75 | 4.01 | 8.78 | 19.37 | 4.82 | 1.40 | 3.41 |

Table 1. The prevalence of health issues among incarcerated women.

| Source | Physical Health Issue Prevalence (%) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Heart Issue | Arthritis Rheumatism | Cirrhosis | STD | Dental Issues | Accidental Injury | Intentional Injury | Influenza | |

| Federal Prisons | 10.33 | 24.32 | 1.25 | 0.42 | 47.08 | 3.13 | 23.07 | 54.07 |

| State Prisons | 8.67 | 23.69 | 1.30 | 1.91 | 47.78 | 8.33 | 17.99 | 45.53 |

| Jails | 8.78 | 19.17 | 1.61 | 1.86 | 28.70 | 3.96 | 6.47 | 36.13 |

Table 1 (continued). The prevalence of health issues among incarcerated women.

| Source | Women Examined While Incarcerated by Persisting Health Issue (%) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cancer | Hypertension | Diabetes | Kidney Issue | Asthma | Hepatitis | Paralysis | Brain Injury | |

| Federal Prisons | 88.89 | 93.27 | 91.38 | 64.86 | 88.81 | 80.43 | 85.71 | 68.75 |

| State Prisons | 68.18 | 90.38 | 89.04 | 56.77 | 83.09 | 80.15 | 66.67 | 70.59 |

| Jails | 25.53 | 56.20 | 67.50 | 28.00 | 44.56 | 27.08 | 25.00 | 32.35 |

Table 2. The examination rates among women experiencing persisting health issues.

| Source | Women Examined While Incarcerated by Persisting Health Issue (%) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Heart Issue | Arthritis Rheumatism | Cirrhosis | STD | Dental Issues | Accidental Injury | Intentional Injury | Influenza | |

| Federal Prisons | 70.71 | 72.53 | 83.33 | 75.00 | 73.61 | 83.26 | 80.00 | 67.95 |

| State Prisons | 72.44 | 63.11 | 76.32 | 69.64 | 85.14 | 84.63 | 76.23 | 67.32 |

| Jails | 32.00 | 26.70 | 34.38 | 40.54 | 46.33 | 57.36 | 44.30 | 44.03 |

44.03

Table 2 (continued). The examination rates among women experiencing persisting health issues.

| Source | Mental Health Issue Prevalence (%) | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Anxiety | Attempted Suicide | Depression | Schizophrenia | Personality | PTSD | Bipolar | Drug Dependence | Other | |

| Federal Prisons | 13.57 | 17.75 | 27.87 | 2.09 | 5.85 | 8.98 | 12.63 | 28.29 | 1.88 |

| State Prisons | 16.42 | 28.63 | 37.34 | 6.76 | 9.73 | 13.92 | 23.96 | 47.88 | 2.66 |

| Jails | 18.06 | 26.04 | 35.02 | 5.67 | 8.58 | 11.14 | 20.07 | 18.87 | 2.86 |

Table 3. The prevalence of mental health issues among incarcerated women.

| Source | Mental Health Information (%) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Any Issue | Medication When Admitted | Medication Since Admitted | Feels Impaired | Received Treatment | |

| Federal Prisons | 52.71 | 12.00 | 25.37 | 6.16 | 19.52 |

| State Prisons | 72.39 | 16.72 | 30.44 | 10.44 | 26.14 |

| Jails | 58.05 | 16.76 | 19.57 | 14.50 | 9.83 |

Table 4. Additional information of the mental health of incarcerated women.

Works Cited

Binswanger, I. A., Krueger, P. M., & Steiner, J. F. (2009). Prevalence of chronic medical conditions among jail and prison inmates in the USA compared with the general population. Journal of Epidemiology & Community Health, 63(11), 912–919. https://doi.org/10.1136/jech.2009.090662

Binswanger, I. A., Merrill, J. O., Krueger, P. M., White, M. C., Booth, R. E., & Elmore, J. G. (2010). Gender Differences in Chronic Medical, Psychiatric, and Substance-Dependence Disorders Among Jail Inmates. American Journal of Public Health, 100(3), 476–482. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2008.149591

Fedock, G., Fries, L., & Kubiak, S. P. (2013). Service Needs for Incarcerated Adults: Exploring Gender Differences. Journal of Offender Rehabilitation, 52(7), 493–508. https://doi.org/10.1080/10509674.2012.759171

Harner, H. M., & Riley, S. (2013). Factors Contributing to Poor Physical Health in Incarcerated Women. Journal of Health Care for the Poor and Underserved, 24(2), 788–801. https://doi.org/10.1353/hpu.2013.0059

Lauren E. Glaze. (2011). Correctional Populations in the United States, 2010 (No. NCJ 236319). Bureau of Justice Statistics.

Meyer, J. P., Zelenev, A., Wickersham, J. A., Williams, C. T., Teixeira, P. A., & Altice, F. L. (2014). Gender Disparities in HIV Treatment Outcomes Following Release From Jail: Results From a Multicenter Study. American Journal of Public Health, 104(3), 434–441. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2013.301553

Mignon, S. (2016). Health issues of incarcerated women in the United States. Ciência & Saúde Coletiva, 21(7), 2051–2060. https://doi.org/10.1590/1413-81232015217.05302016

R Core Team. (2017). R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing. Vienna, Austria: R Foundation for Statistical Computing. Retrieved from https://www.R-project.org/

Rose, S. J., Lebel, T. P., Begun, A. L., & Fuhrmann, D. (2014). Looking Out from the Inside: Incarcerated Women’s Perceived Barriers to Treatment of Substance Use. Journal of Offender Rehabilitation, 53(4), 300–316. https://doi.org/10.1080/10509674.2014.902006

Sufrin, C. B., Creinin, M. D., & Chang, J. C. (2009). Incarcerated Women and Abortion Provision: A Survey of Correctional Health Providers. Perspectives on Sexual and Reproductive Health, 41(1), 6–11. https://doi.org/10.1363/4100609

Todd D. Minton. (2012). Jail Inmates at Midyear 2011 - Statistical Tables (No. NCJ 237961). Bureau of Justice Statistics.

United States Department of Justice. Bureau of Justice Statistics. (2006). Survey of Inmates in Local Jails, 2002 [United States]: Version 2 [Data set]. Inter-university Consortium for Political and Social Research. https://doi.org/10.3886/ICPSR04359.v2

United States Department Of Justice. Office Of Justice Programs. Bureau Of Justice Statistics. (2007). Survey of Inmates in State and Federal Correctional Facilities, 2004. ICPSR - Interuniversity Consortium for Political and Social Research. https://doi.org/10.3886/ICPSR04572.v2

The simple fact of being under the regas has repercussions at a psychic level, among them anxiety, hopelessness and feelings of abandonment, this is clearly stated by the research that quotes can generate somatizations, which is the incidence of said pathologies.

Downvoting a post can decrease pending rewards and make it less visible. Common reasons:

Submit

I would love to see these statistics contrasted with assisted living facilities or homes for the elderly. Very interesting. Thought provoking. Should we be doing a better job within the prison system or trying to abolish it by diverting people out and away from prison as a last resort.

Downvoting a post can decrease pending rewards and make it less visible. Common reasons:

Submit

I assume it has to do with the quality and the level of a facility too? State prisons seem to be the worst...

Downvoting a post can decrease pending rewards and make it less visible. Common reasons:

Submit

very nice bro good post

Downvoting a post can decrease pending rewards and make it less visible. Common reasons:

Submit

Congratulations @somethingburger! You have completed some achievement on Steemit and have been rewarded with new badge(s) :

Click on any badge to view your own Board of Honor on SteemitBoard.

For more information about SteemitBoard, click here

If you no longer want to receive notifications, reply to this comment with the word

STOPDownvoting a post can decrease pending rewards and make it less visible. Common reasons:

Submit

Congratulations @somethingburger! You have completed some achievement on Steemit and have been rewarded with new badge(s) :

Click on any badge to view your own Board of Honor on SteemitBoard.

For more information about SteemitBoard, click here

If you no longer want to receive notifications, reply to this comment with the word

STOPDownvoting a post can decrease pending rewards and make it less visible. Common reasons:

Submit

Congratulations @somethingburger! You have completed some achievement on Steemit and have been rewarded with new badge(s) :

Click on any badge to view your own Board of Honor on SteemitBoard.

For more information about SteemitBoard, click here

If you no longer want to receive notifications, reply to this comment with the word

STOPDownvoting a post can decrease pending rewards and make it less visible. Common reasons:

Submit

Congratulations @somethingburger! You have received a personal award!

Click on the badge to view your Board of Honor.

Do not miss the last post from @steemitboard:

SteemitBoard World Cup Contest - The results, the winners and the prizes

Downvoting a post can decrease pending rewards and make it less visible. Common reasons:

Submit

@somethingburger you were flagged by a worthless gang of trolls, so, I gave you an upvote to counteract it! Enjoy!!

Downvoting a post can decrease pending rewards and make it less visible. Common reasons:

Submit