The Restoration of Ancient History is a paper delivered in November 1994 by Gunnar Heinsohn, Professor Emeritus at the University of Bremen in Germany, at a symposium in Portland, Oregon. This paper questions the conventional chronology of ancient history and offers in its place a radical reconstruction—the so-called Short Chronology, of which Heinsohn is the principal architect. In this series of articles, we are taking a closer look at the evidence cited in this paper in favour of Heinsohn’s new chronology:

In the last article, we reviewed Heinsohn’s reconstruction of the chronology of Ancient Israel, which drastically shortens the timeline of Israelite history. Heinsohn dated the Exodus to the end of the Middle Bronze Age, when the Hyksos were expelled from Egypt. In the conventional chronology the Expulsion of the Hyksos took place in the mid-sixteenth century BCE, but Heinsohn dated it to 630 BCE—more than a century later than the date I favour (763 BCE).

The Expulsion of the Hyksos had serious consequences for Palestine:

The most significant event concerning Palestine was the expulsion of the Hyksos from Egypt in the mid-sixteenth century B.C.E. The Hyksos princes fled from the eastern Delta of Egypt to southern Palestine; the Egyptians followed them there and put them under siege in the city of Sharuhen. This event was probably followed by turmoil and military conflicts throughout the country, as a significant number of Middle Bronze cities were destroyed during the mid-sixteenth century B.C.E. These destructions caused a collapse in entire urban clusters in the country. Thus, in the south, cities along Beersheba and Besor brooks were destroyed, and they hardly continued to exist in the following period ... In the coastal plain and the Shephelah, Tell Beit Mirsim, Gezer, Tel Batash and Aphek suffered from destructions and severe changes in their occupation history. In the northern coastal plain, the large city at Kabri was abandoned. In the central hill region and the Jordan Valley, a chain of Middle Bronze cities and villages came to an end, and only few revived in the following period. Examples are Jericho,Hebron, Beth-Zur, Jerusalem, and Shiloh. (Heinsohn)

In his lecture, Heinsohn discussed one of these cities in Palestine:

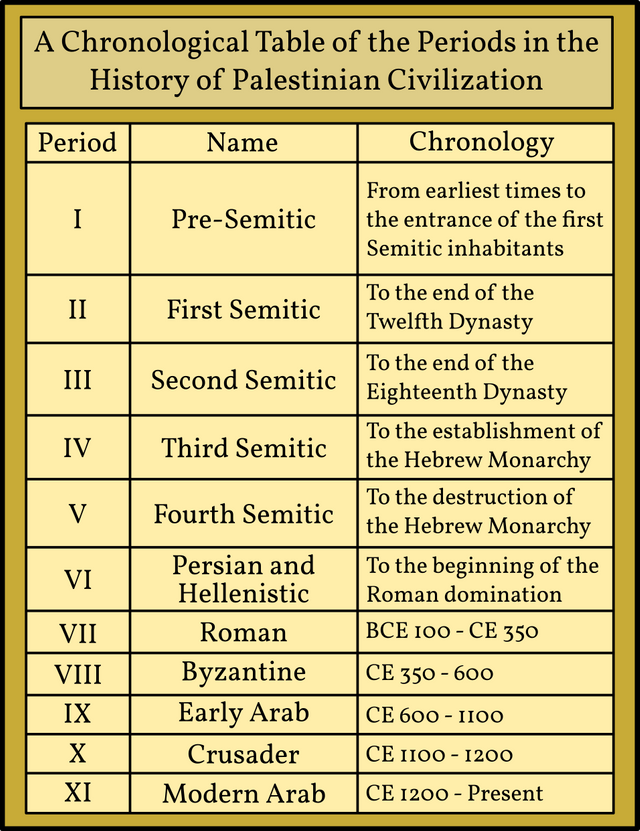

Macalister’s Gezer dates and terminology (1912)

In this article we will take a look at the results of Macalister’s excavations and see how these relate to the competing chronologies of ancient Canaan.

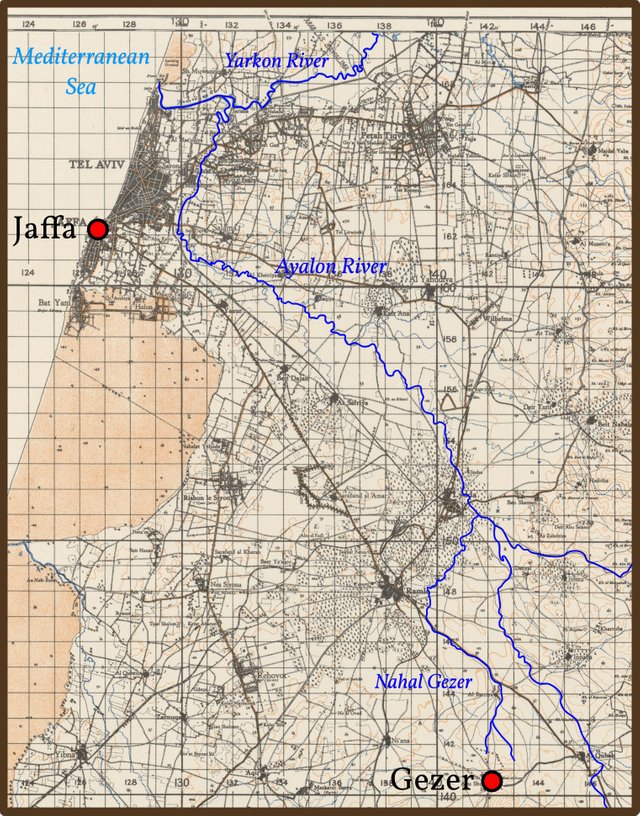

Gezer

Gezer was an ancient Canaanite city located on the eastern edge of the Shephelah, a low-lying stretch of land in central Palestine, between the Judaean Hills and the Coastal Plain. The ruins of the city sit upon a hill at the head of a valley, from which the Nahal Gezer rises. This stream joins the Ayalon River about 10 km north of Gezer. The Ayalon, in its turn, flows into the Yarkon River about 6.5 km northeast of Jaffa. The Yarkon debouches into the Mediterranean Sea in the northern suburbs of the modern city of Tel Aviv.

The Canaanite city was well fortified and of sufficient importance to be mentioned several times in Egyptian records. It is also mentioned several times in the Old Testament, though the Biblical account of Gezer is inconsistent. According to Joshua 10:33, Horam King of Gezer was defeated by Joshua when he came to the aid of the city of Lachish, 33 km south of Gezer. In Joshua 16:10 it is said that the city of Gezer fell to the Ephraimites, but they failed to drive out the Canaanites: the Canaanites dwell among the Ephraimites unto this day. In Joshua 21:21, Gezer is identified as one of the four cities which the Ephraimites give to the children of Kohath of the Tribe of Levi. In Judges 1:24, we are told that the Ephraimites did not drive out the Canaanites from Gezer but that the Canaanites dwelt among the Ephraimites. Finally, in 1 Kings 9:15-16, Gezer is identified as one of the fortified cities of King Solomon, For Pharaoh king of Egypt had gone up, and taken Gezer, and burnt it with fire, and slain the Canaanites that dwelt in the city, and given it for a present unto his daughter, Solomon's wife.

Gezer survived the fall of the Kingdoms of Israel and Judah and was inhabited continuously until sometime between 100 BCE (Macalister xxiii) and 100 CE (Dever 62). During the Crusades, the hill on which it sits was called Mont Gisart. At some indeterminate time, an Arab village called Abu Shusha was established on the lower slopes of the western mound. Today the site of Tel Gezer is an Israeli National Park.

Macalister

In 1871, the French Orientalist Charles Simon Clermont-Ganneau identified the Palestinian village of Abu Shusha as the site of the ancient city of Gezer. The first excavations were carried out here between 1902 and 1909 on behalf of the Palestine Exploration Fund. The director of these excavations was Robert Alexander Stewart Macalister, an Irish scholar and archaeologist.

R A S Macalister was born in Dublin in 1870. His father, Alexander Macalister, was an anatomist and Egyptologist. In 1869, he was appointed Professor of Zoology at Trinity College Dublin. When Robert was thirteen, his father became Professor of Anatomy at Cambridge University and the family relocated to England. In 1892, Robert graduated from St John’s College, Cambridge, in mathematics, but his main interests were in the fields of geology and archaeology.

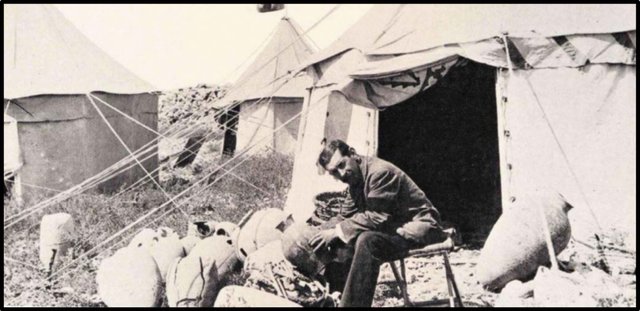

His professional life fell into two parts: one as an excavator employed by the Palestine Exploration Fund; the other as professor of Celtic archaeology at UCD (1909–43). Between 1898 and 1909 he worked in Palestine, mainly at Gezer. The site, written up in three volumes (1912), marks a turning point in archaeological reports in precision of detail, although his excavation methods may be faulted in the light of advanced techniques. It was a huge task for one man alone to oversee up to 200 workmen. He was granted leave of absence to return to Jerusalem, where his name is still respected, to direct the Hill of Ophel, City of David, excavation (1923–5). His work in Palestine is embodied in over fifty separate publications; his compact A History of Civilization in Palestine (1912) had a wide circulation. (Hilary Richardson)

In 1912, his report on the excavations at Gezer was published in three volumes. It is this work that Heinsohn cites.

Macalister’s Gezer Stratigraphy

Macalister identified eleven periods in the history of Palestine. The earliest of these represented in his opinion a pre-Semitic culture, to which he gave the unflattering name of Troglodytes. The following four periods he identified as Semitic. These cover the Canaanite and Israelite eras. The sixth period was Persian and Hellenistic—why are these lumped together?—the seventh Roman, the eighth Byzantine, the ninth early Arab, the tenth Crusader, and the eleventh modern Arab. There is nothing revolutionary here. Macalister’s chronology is in line with the mainstream archaeology of his day:

It is not surprising that Macalister fitted the various strata at Tel Gezer into this chronological model, which was assumed at the outset to represent the actual timeline of Palestinian history:

The stratification of Eastern and especially of Palestinian cities is a phenomenon which recent excavations have made so familiar that it is unnecessary to describe it here at length. Let it suffice to say that houses have always been built over the ruins of their predecessors; that these houses were built of mud-brick or of stones set in mud, from which the winter rains annually wash out a considerable quantity of clay; that rubbish and organic matter were allowed to accumulate in the city streets; and that thus the level of the city became raised at a rate variously estimated—at Gezer I reckon it to be about an inch [2.5 cm] in six years. (Macalister 158-159)

Macalister’s excavation of Gezer commenced with the digging of a series of trenches at the eastern end of the tell. Each trench was 40 ft [12 m] wide and ran the entire length of the tell, and each was excavated down to the bedrock. In some cases, this resulted in a trench 42 ft, or about 13 m, deep. Taking Macalister’s estimate of 1 inch = 6 years, this implies an age of 3024 years for the site. As Macalister believed that Tel Gezer was finally abandoned around 100 BCE, this would seem to imply that the lowest stratum corresponds to 3124 BCE. Macalister actually placed the initial occupation of the site by Pre-Semitic cave-dwellers (Troglodytes) at not much later than 3000 BCE (Macalister 6).

The complex stratification of Tel Gezer presented problems from the outset:

The study of the strata at Gazer is in consequence peculiarly complex. In some parts of the hill certain of the epochs of the city’s history are completely unrepresented, and we must suppose that during those epochs the regions in question were deserted areas; while on the other hand periods represented by single strata in some parts of the mound are found to involve two or three in others ...

... Where possible, the simplest and best way of giving this information is by stating in which stratum an object happened to be found; but in the case of Gezer this method is not admissible, owing to the irregularity of the stratification—in some parts of the mound only two strata were found, in others eight. (Macalister 160 ... 55)

Macalister identified a total of eight strata at Gezer (Webb 14). He numbered these from earliest to youngest, and assigned them to the following periods (I have replaced Macalister’s Roman numerals with modern Hindi-Arabic numerals):

| Stratum | Period | Conventional Chronology |

|---|---|---|

| 8 | Roman | 100 BCE-350 CE |

| 7 | Hellenistic | 300-100 |

| 6 | Persian | 550-300 |

| 5 | Fourth Semitic | 1000-550 |

| 4 | Third Semitic | 1300-1000 |

| 3 | Second Semitic | 1800-1300 |

| 2 | First Semitic | 2500-1800 |

| 1 | Pre-Semitic Troglodytes | 3000-2500 |

Note that Macalister assigned two separate strata to the Persian & Hellenistic Period:

Secondly, it may sometimes be convenient to divide the sixth period into two subdivisions; the first of these (from B.C. 550 to 300) may fittingly be called the Persian period, and the second the Hellenistic proper. (Macalister 57)

As we have seen, Macalister believed that the tell itself was abandoned around the beginning of the Roman Period:

c 100 [BCE] About this time the boundary inscriptions cut, and the hill-top site deserted by the inhabitants, who settle in the neighbouring villages. (Macalister xxiii)

William G Dever believes that this abandonment took place in the 1st century CE (Dever 62).

In The Excavation of Gezer, Macalister explains why the remains of so many cities in the Ancient World are stratified:

If it could be proved that a city was fully occupied during its whole history, and that the stratification of successive layers of building was due to a series of catastrophes by which the whole area of the town was wrecked several times, the case would be comparatively simple; and if we were acquainted with the nature and date of each of these catastrophes, we would then have no difficulty in assigning to their proper period the various remains of walls unearthed in excavation. (Macalister 160-161)

In the case of Gezer, this ideal model is confounded by three factors:

(1) There is no possibility of distinguishing date from an inspection of the buildings themselves. From first to last all are of the same rude construction and plan, or rather want of plan ...

(2) The great area included within the walls was not all occupied at once. There were many open spaces here and there at all times. In consequence, the number of strata ranges from two to eight ...

(3) There were no great universal catastrophes which destroyed the whole city at once. There are plenty of signs of large local fires, but no all-covering bed of ashes (like that most welcome layer at Tell el-Hesy). The captures and lootings of successive Pharaohs did a great deal of damage to the structures of the city, but in no case made “a clean sweep” of the whole. Many individual houses survived the storm and stress, and each one is a centre of difficulty and unsuspected inaccuracy to the would-be plotter of the city. (Macalister 161)

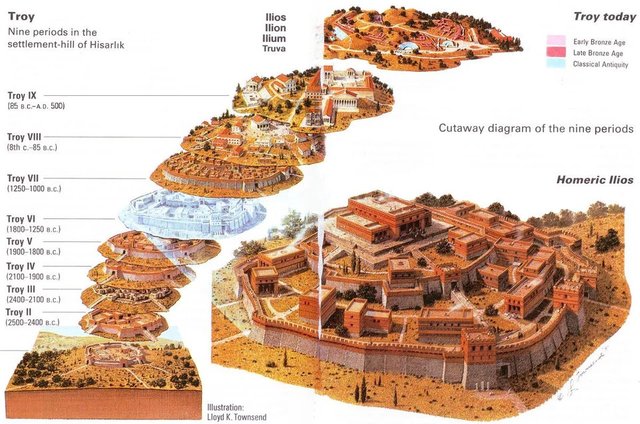

Many modern archaeologists seem reluctant to accept that the stratification of an ancient city was a direct consequence of catastrophic destruction—whether partial or complete, whether natural or by the hand of man—of the site. The survivors would level the site and rebuild on top of the ruins of the previous settlement. This is how the hill of Hisarlik came to entomb nine Troys superimposed one upon the other.

Note that Macalister’s attribution of the stratification of Gezer to repeated razing and rebuilding of the city contradicts what he wrote on the previous page (Macalister 159) about the winter rains gradually washing away the mud bricks from which the city was constructed, while rubbish was allowed to accumulate in the streets. This scenario seems to suggest that the stratification was a continuous process that went on year by year, and not the result of punctuated catastrophes. I do not see how the continuous erosion of the buildings and accumulation of refuse in the streets could possibly result in a stratified tell, with several successive settlements superimposed one upon the other.

Stratification implies catastrophism.

Gezer’s Modern Stratigraphy

The stratigraphy and chronology of Gezer is acknowledged to be complex and difficult to disentangle:

Gezer has become one of the most contested archaeological sites in Israel. Almost every stratum, building and issue related to the mound has turned into a source of contention and dispute. (Finkelstein 263)

Today, archaeologists recognize no less than twenty-six strata at Tel Gezer. But is this really credible? The consequence seems to be that the ancient city was destroyed and rebuilt twenty-five times in the course of its history. Modern archaeologists do not actually make any such claim. They emphasize the continuity between successive eras at the expense of catastrophic interruption:

The analysis shows that from the Middle Bronze Age through the end of the Iron Age, Gezer experienced long periods of ethnic continuity as well as shorter phases of ethnic variety. During the Bronze Age, the city was the quintessential Canaanite city- state. It continued to be largely Canaanite in the Early Iron Age, though it was ethnically mixed having a minority of Philistines occupying part of the site. In the Late Iron Age the ethnic balance shifted as the site became gradually more Israelite, being completely Israelite by the end of the Iron Age. This study demonstrates that ethnic identity was an existing form of social identity in antiquity and is capable of being revealed in the historical and archaeological record. (Webb iv)

And this continuity was not only ethnic. It is also observed in the material culture of the city:

The ceramic evidence from Gezer reveals a great deal of continuity between the Middle Bronze and the Late Bronze ... What is striking about Iron I Gezer is “the strong evidence of ceramic continuity ... which sees the persistence of a number of LB IIB forms and styles of decoration” [Dever] ... During the early Iron Age the Philistines were definitely one ethnic component at Gezer. It is unclear how many Philistines occupied Gezer, it seems they were a minority, though likely dominant politically. The Canaanites were the other ethnic component at Gezer in the early Iron Age. There was continuity between the Bronze Age and Iron Age. The descendants of the Bronze Age Canaanite inhabitants continued to live in the Iron Age city, alongside the newcomers. (Webb 75 ... 148 ... 193)

But if this continuity precludes large-scale destruction at the end of one stratum, there would not have been a new stratum. How can there be stratification without successive catastrophes? Cultural and ethnic continuity across a stratigraphic interface simply means that the survivors rebuilt in the immediate aftermath of a catastrophe and took up, culturally speaking, where they had left off.

These twenty-six strata were identified by accumulating the strata discovered at several different parts of the site during the excavations carried out on behalf of the Hebrew Union College between 1967 and 1974:

Gezer was first excavated between 1902 and 1909 by R.A.S. Macalister on behalf of the Palestine Exploration Fund. Macalister exposed large parts of the mound in a series of parallel trenches and uncovered almost all of the famous Gezer monuments (Macalister I-III). A second dig, limited in scope, was conducted at the site by A. Rowe in 1934. The third expedition worked at Gezer from 1964 to 1974 on behalf of the HUC Biblical and Archaeological School in Jerusalem (Gezer I-V). It was led by G.E. Wright (1964-1965), W.G. Dever (1966-1971) and J.D. Seger (1972-1974) ... The HUC team operated in ten fields and touched on the entire history of the site, from the Chalcolithic to the Hellenistic periods—an accumulation of 26 strata. (Finkelstein 262 ... 263)

It need hardly be pointed out that none of the ten fields featured all twenty-six strata. It could be argued, then, that the HUC’s twenty-six strata include several duplicates, where the same stratum observed in different fields was counted more than once.

The dating of these strata is still a matter of scholarly dispute. In 2002, the Israeli archaeologist Israel Finkelstein proposed a new chronology—the Low Chronology—which is at odds with the High Chronology devised in the ’60s by Wright, Dever & Seger of the HUC. The resulting debate between Finkelstein and the American archaeologist William G Dever was heated and acrimonious:

Dever also has a long and bitter feud with fellow archaeologist Israel Finkelstein, whom he has described as “idiosyncratic and doctrinaire” and “a magician and a showman”, to which Finkelstein answered by calling Dever “a jealous academic parasite” and “a biblical literalist disguised as a liberal”. A 2004 debate between Finkelstein and William G. Dever, mediated by Hershel Shanks (editor of the Biblical Archaeology Review), quickly degenerated into insults, forcing Shanks to halt the debate. Shanks described the exchange between the two as “embarrassing”. (Wikipedia)

Macalister’s Legacy

Macalister’s chronology of the Gezer stratigraphy is at odds with both of the competing chronologies, Dever’s High Chronology and Finkelstein’s Low Chronology. For example, Macalister’s “Maccabean Castle” is now identified as a “Solomonic Gate” by the High Chronologists, while the Low Chronologists place it a century later in the reign of King Ahab of Israel. (Webb 16).

While Macalister is still acknowledged to have been an able archaeologist, whose work at Gezer introduced a new level of professionalism to the field of Biblical excavation, his conclusions are dismissed and the man himself is generally damned with faint praise:

Between 1902 and 1909, the Irish archaeologist R. A. S. Macalister excavated Gezer on behalf of the Palestine Exploration Fund. It was the largest excavation ever undertaken in Palestine. Macalister, working alone except for an Egyptian foreman, supervised up to 400 Arab laborers. Macalister’s plan was nothing if not ambitious. His intention was “to turn over the entire mound,” from ground level to bedrock. His method was to dig trenches ten meters wide, one after the other, across the entire width of the tell, an unrefined technique known as the trenching system. The debris from the second trench was simply dumped into the first trench and so on. It is impossible to understand the tell’s stratigraphy in this way (Macalister identified nine strata; more recent excavators identified 26). Even with 400 workmen and a seven-year effort, Macalister’s goal proved to be unachievable. His reports to the Palestine Exploration Fund began to be repetitive; as a result, the excavation’s financial backers withdrew support and Macalister was forced to abandon the project.

But to his everlasting credit, Macalister promptly produced three thick volumes reporting on the excavation. They are a mine of information—and misinformation. But even with his primitive methodology, by today’s standards, his results were impressive.

Perhaps it is fortunate Macalister was never able to complete his project, “to turn over the whole mound.” If he had been successful in doing this, there would have been nothing left for later, far better equipped archaeologists to work with. (Hershel Shanks)

A few years ago, the centenary of the publication of The Excavation of Gezer was marked by a volume of essays by twenty experts in the field in which Macalister’s archaeological work in Palestine was reassessed. The title of this collection, Villain or Visionary? testifies to the ambivalence with which Macalister and his legacy are regarded. The comments of Samuel R Wolff, Gary Arbino and Steven Ortiz, of the Tandy Excavation at Gezer (2006-2008) are typical of the more negative contributors to this volume:

To summarize, then, we have much respect and admiration for what Macalister accomplished in our area at Gezer. He drew for the most part detailed and often accurate architectural plans and collected and published all of the important material from the area; it is unfortunate that even an approximate location for these finds cannot be ascertained from the publication. It remains for the Tandy expedition to analyse and separate out the various architectural phases from his ‘Hellenistic period’ plan.

Our final comment: thank goodness that Macalister did not dig down to bedrock in our area! Had he done so, he would most probably not have been able to distinguish and date the important Iron II phases that our excavation is encountering. (Wolff 49)

On the other side of the debate lies Jonathan N Tubb:

It was at Gezer that Macalister showed himself as an intellectual giant. His work there represents a monumental milestone in the development of Palestinian archaeology, and he deserves the utmost respect of scholars and practitioners of Levantine archaeology. (Wolff 19)

Five essays spanning thirty-two pages of this book are devoted to Macalister’s excavations at Tel Gezer:

Joe D Seger: R. A. S. Macalister and Gezer

Samuel R Wolff, Gary Arbino, Steven Ortiz: Macalister at Gezer: A Perspective from the Field

Baruch Brandl: Are the Finds from Macalister’s Gezer I–III Still Relevant for Current Research a Century Later?

Daniel A Warner, Tsvika Tsuk, Jim Parker: The Gezer Water System Re-examined

Eric Mitchell: The Gezer Survey: An Assessment of Macalister’s Work

Unfortunately, these essays are not freely accessible online.

Heinsohn on Macalister

The Restoration of Ancient History comprises Heinsohn’s lecture notes, not the complete text of the talk he gave in Oregon in 1994. I do not know what he had to say about Macalister’s excavations at Tel Gezer. In 1988, however, Heinsohn published Die Sumerer gab es nicht [The Sumerians Never Existed]. In this book, he discusses Megiddo and presents his revised chronology of the strata. He does not discuss Gezer, but in his discussion of the stratigraphy of Megiddo he does refer to the stratigraphies of Gezer and Hazor as «Schwester»-Stratigraphien, or “Sister”-Stratigraphies (Heinsohn 1988:256).

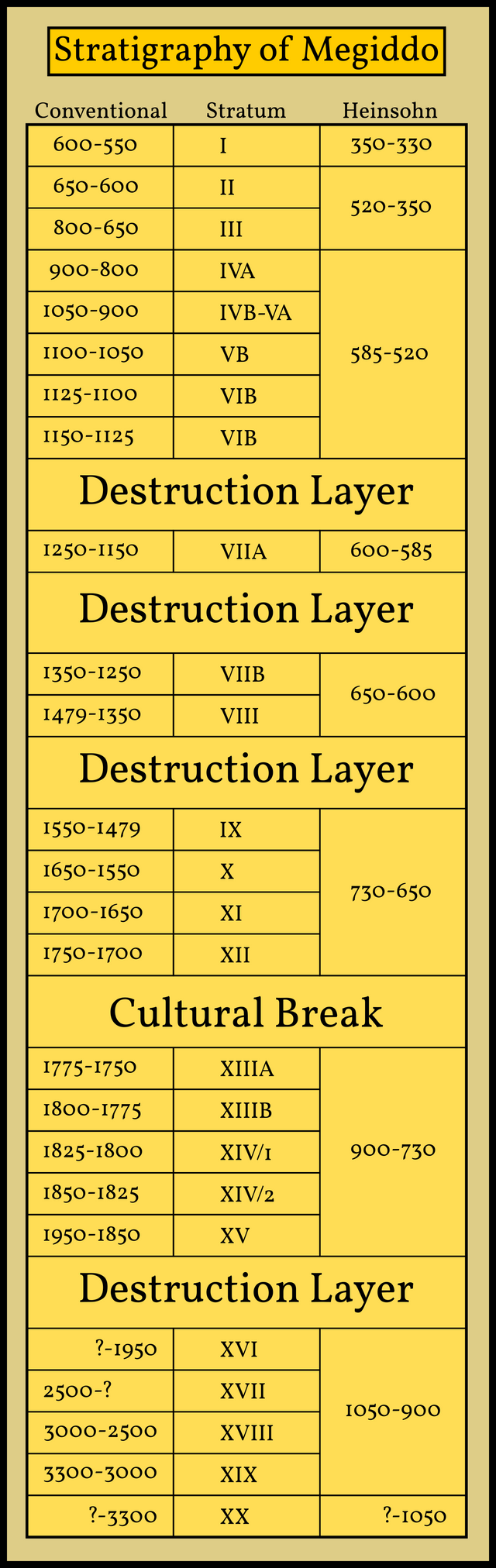

Let us compare, then, Heinsohn’s chronology and the conventional chronology of the stratigraphy of Megiddo. Note that the main difference between the two is the same as the main difference between Macalister’s and mainstream archaeology’s Gezer stratigraphies: the great disparity in the number of strata. Contemporary archaeologists recognize no less than twenty major strata at Tel Megiddo and several minor ones. Heinsohn, however, only recognizes a stratum break when there is either a destruction layer (implying a catastrophic razing of the site) or a cultural break (implying a temporary abandonment of the site). This analysis reduces the number of principal strata at Tel Megiddo to six, with a few minor ones.

The other notable difference between the two chronologies is the length of time they assign to the history of Megiddo. Conventional archaeologists place the earliest settlement of the tell to the Neolithic, ending around 3300 BCE, and the final abandonment of the site to 586 BCE or so. Heinsohn tentatively dates the end of the earliest settlement to 1050 BCE and the abandonment of the site sometime after 330 BCE in the early Hellenistic period:

It is tempting to adapt Heinsohn’s Megiddo chronology and apply it to Gezer, but this would be misleading. Die Sumerer gab es nicht was published in 1988, six years before The Restoration of ancient History. In the course of those six years, Heinsohn’s opinions continued to evolve. In 1988, he dated the Exodus to sometime before 1050 BCE and still recognized the Neo-Assyrians and Neo-Babylonians as Akkadians. By 1994, however, he was dating the Exodus to 630 BCE and identifying the Neo-Assyrians and Neo-Babylonians with the Persians. Nevertheless, his 1988 Megiddo chronology gives us some idea of the shortened timeline of his Gezer chronology.

Last Words

R A S Macalister lived in an age when archaeology was still in its infancy. Today, every scrap of ancient material, no matter how mundane it may have been to the ancients who discarded it, is valued and carefully preserved. But this was not the case a century ago:

Each pit was sunk to the rock, over its whole surface, before the next was begun. At first the walls on the rock were left standing; but as it was found that sometimes they concealed the entrances to caves, the broader walls of the lowermost strata were cleared away. Of course it was necessary entirely to demolish all walls of the upper strata: the only exceptions made being a few buildings such as the Maccabaean castle, the Syrian bath-house, the reservoirs in VI 18, the large Canaanite castle in IV 15, 16, and the temple in IV 27-29. These buildings were considered too valuable to destroy, and the underlying debris of earlier periods was in each case abandoned without examination. (Macalister 48)

Whether he was a villain or a visionary, it is possible that R A S Macalister came closer to unearthing the true history of Gezer than any of his successors.

And that’s a good place to stop.

References

- William G Dever, Excavations at Gezer, The Biblical Archaeologist, Volume 30, Number 2, Pages 47-62, The American Schools of Oriental Research, The University of Chicago Press, Chicago (1967)

- Israel Finkelstein, Gezer Revisited and Revised, Tel Aviv, Volume 29, Issue 2, Pages 262-296, Institute of Archaeology of Tel Aviv University, Tel Aviv (2002)

- Gunnar Heinsohn, Catastrophism, Revisionism, and Velikovsky, in Lewis M Greenberg (editor), Kronos: A Journal of Interdisciplinary Synthesis, Volume 11, Number 1, Kronos Press, Deerfield Beach, FL (1985)

- Gunnar Heinsohn, The Restoration of Ancient History, Mikamar Publishing, Portland, OR (1994)

- Gunnar Heinsohn, Die Sumerer gab es nicht [The Sumerians Never Existed], Frankfurt (1988)

- Gunnar Heinsohn, Heribert Illig, Wann lebten die Pharaonen? [When Did the Pharaohs Live?], Eichborn Verlag, Frankfurt (1990)

- Gunnar Heinsohn, M Eichborn, Wie alt ist das Menschengeschlecht? [How Old Is Mankind?], Mantis Verlag, Gräfelfing, Munich (1996)

- Robert Alexander Stewart Macalister, The Excavation of Gezer: 1902-1905 and 1907-1909, Volume 1, Volume 2, Volume 3, John Murray, London, (1912)

- Hilary Richardson, Macalister, Robert Alexander Stewart, in Dictionary of Irish Biography, Royal Irish Academy, Online Edition (2009)

- Hershel Shanks, The Sad Case of Gezer, Biblical Archaeology Review, Volume 9, Number 4, Biblical Archaeology Society, Washington, DC (1983)

- Philip Webb, Ethnic Continuity and Change at Gezer, San Jose State University, _Master’s Theses_, Number 4370, San Jose (2013)

- Samuel R Wolff (editor), Villain or Visionary? R. A. S. Macalister and the Archaeology of Palestine, Routledge, London, (2015)

Image Credits

- R A S Macalister: Dermod O’Brien (artist), Royal Irish Academy, Academy House, Dublin, Public Domain

- Tel Gezer and Environs: Jaffa Tel Aviv, The War Office, Perry-Castañeda Library (PCL) Map Collection, University of Texas Libraries, The University of Texas at Austin, Public Domain

- R A S Macalister at Gezer (1905): Near Eastern Archaeologist, Public Domain

- Gezer: Canaanite Tower: © Mujaddara, Creative Commons License

- William G Dever: © 2020 William G Dever, Fair Use

- Nine Troys: © Lloyd K Townsend (artist), Fair Use

- Gezer: Canaanite City Gate: © Gerald R Flurry, Watch Jerusalem, Fair Use

- Israel Finkelstein: © Argonauter, Creative Commons License

- Maccabean Castle or Solomonic Gate?: © Madain Project 2017 - 2021, Fair Use

- Gezer Boundary Stone Number 5: HaMeginim Forest (2 km SSE of Tel Gezer), © Oren Rozen, Creative Commons License

Online Resources