The Restoration of Ancient History is a paper delivered in November 1994 by Gunnar Heinsohn, Professor Emeritus at the University of Bremen in Germany, at a symposium in Portland, Oregon. This paper questions the conventional chronology of ancient history and offers in its place a radical reconstruction—the so-called Short Chronology, of which Heinsohn is the principal architect. In this series of articles, we are taking a closer look at the evidence cited in this paper in favour of Heinsohn’s new chronology:

Heinsohn recognizes four periods in the history of Mesopotamia before the conquests of Alexander the Great:

| Dates BCE | Assyria | Babylonia |

|---|---|---|

| 1150-750 | Early Assyrians | Early Chaldaeans |

| 750-620 | Assyrian Empire | Assyrian Empire and Scythians |

| 620-540 | Empire of the Medes | Neo-Chaldaeans |

| 540-330 | Persian Empire | Persian Empire |

In this article we will conclude our survey of Part 3 of Heinsohn’s lecture: Archaeologically-missing history and historically-unexpected archaeology in major areas of antiquity.. One of the cornerstones of Heinsohn’s model of the Short Chronology is the identification of the Kingdom of Mitanni with the Empire of the Medes, and of the Middle and Neo-Assyrian Empires with the Persian Empire:

| BCE | Conventional | Heinsohn | Short Chronology |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1600-1250 | Mitanni | Empire of the Medes | 620-540 |

| 1392-609 | Middle & Neo-Assyrian Empires | Persian Empire | 540-330 |

These identifications were forced on Heinsohn by the stratigraphy of Upper Mesopotamia and Iran:

Core-Satrapies: Armenia, Assyria and Cappadocia. Iranian Heartland with structures in Pasargade, Persepolis, rock tombs etc. Hellenism built on nothing but pre-600 or older ruins in satrapies conquered against strong resistance after - 333.

550-330 BCE (Greek dates): absence of finds for imperial dimensions, but also absence of aeolic layer for gap ...

900-600 BCE (Biblical dates): most impressive finds before empire, which stratigraphically sit directly

beneath Hellenism. Absence of archaeological finds out of which the later Persians could develop the skills and architecture of their forefathers ...Only if stratigraphy is allowed to replace conventional dating schemes, the -900 to -600 structures in, e.g., Armenia and Assyria, instantly materialize as the hard evidence of Persia’s core-satrapies. What the Ancients considered as the most powerful rulers of all times before the Roman Empire suddenly become visible in the annals of Assyria excavated in the 19th and 20th century. (Heinsohn)

One of the inevitable consequences of Heinsohn’s realignment is that the kings of Mitanni and Assyria must be identical to the Median and Persian emperors. The former were largely unknown until the archaeologists recovered ancient cuneiform records and deciphered them, whereas the latter were already well-known thanks to Classical historians like Herodotus, Xenophon, and Diodorus Siculus. A few of the former, it is true, are mentioned in the Bible. On the other hand, some ancient historians—eg Ctesias and Berossus—have left accounts that are strikingly divergent from the better-known chronicles of Herodotus, Xenophon and Diodorus. There are even a few troubling discrepancies among the latter: see, for example, Cyaxares II, whose existence is attested to by Xenophon but not by Herodotus.

Heinsohn briefly mentions the following possible parallelisms between the royal names deciphered by the Assyriologists and those recorded by the Classical historians:

| Assyriology | Greek | Aramaic |

|---|---|---|

| Sin-shar-ishkun | Darius III | Codomannus |

| Assur-etil-ilani | Artaxerxes IV | Arses |

| Assurbanipal | Artaxerxes III | Ochus |

| Esarhaddon | Artaxerxes II | Arsaces |

| Sennacherib | Darius II | Ochus |

| Shalmaneser III + Sargon II (Israel: Shalmaneser’s vassal Jehu) | Artaxerxes I | - |

| Ashurnasirpal II | Xerxes I | - |

| Tukulti-Ninurta II | Darius I | - |

| Shalmaneser I | Cambyses II | - |

| Adad-nirari I | Cyrus the Great | Adad-nirari II |

| Shutarna III | Astygages the Mede | - |

| Shaushatra | Cyaxares the Mede | - |

| Khuwaruwash | Phraortes the Mede | - |

| Naram-Sin of Akkad | Ninus of Assyria | - |

| Sargon of Akkad | Sharek + Salitis of the Hyksos | - |

In his earlier work, Die Sumerer gab es night, which was first published in 1988, Heinsohn’s alter egos were significantly different:

| Tentative Dates | Alter Ego 1 | Alter Ego 2 | Alter Ego 3 |

|---|---|---|---|

| 358-338 | Artaxerxes III Ochus | Ammisaduqa | - |

| 521-486 | Darius I | Hammurabi | - |

| 555-539 | Nabonidus | Ibbi-Sin | Tudhaliya IV |

| 650-547 | Adad-Guppi | Puduhepa | - |

| 604-562 | Nebuchadnezzar II | Shulgi | Hattusilis III |

| 625-605 | Nabopolassar | Ur-Nammu | Mursilis II |

| 653-585 | Cyaxares | Shaushatra | - |

| 614-609 | Assuruballit II | Assuruballit I | - |

| 680-669 | Esarhaddon | Naram-Sin of Akkad | Naram-Sin of Assyria |

| 704-681 | Sennacherib | Manishtushu | - |

| 721-705 | Sargon II | Sargon of Akkad | Sargon I, Sarek the Hyksos |

| 721-710 | Merodach-Baladan II | Merodach-Baladan I | Lugalzagesi |

| 746-734 | Nabonassar | Urukagina | - |

(Heinsohn 2007:233)

Clearly, this model was heavily influenced by Immanuel Velikovsky’s chronology, which was the jumping-off point for Heinsohn’s reconstructions. When Heinsohn wrote Die Sumerer gab es nicht, he had not yet made the connection between the Neo-Assyrians and the Persians. His dates for the Neo-Assyrians and Neo-Babylonians are in line with the conventional chronology. He followed Velikovsky in identifying the Medes with the Mitannians, and the Neo-Babylonians with the so-called Hittites. He also identified the Persians with the Old Babylonians, which Velikovsky had never ventured to do. In Die Sumerer gab es nicht, Heinsohn also hypothesized that the Israelite Kings Solomon and David were conflations of mythical figures—“anthropomorphized astral heroes”—and two Neo-Assyrian Emperors, Tiglath-Pileser III and Shalmaneser III (Heinsohn 2007:250).

All of this was to be radically altered, however, in the following five or six years, when Heinsohn ruthlessly applied the stratigraphic method to the history of the Ancient World. The resulting Short Chronology was not only at odds with mainstream academy: it also overturned many of Velikovsky’s most cherished beliefs.

Heinsohn’s revised chronology is not without its own difficulties. Note that he omits several Neo-Assyrian Emperors, whose existence is attested by monuments and cuneiform records (Luckenbill passim): Shamshi-Adad V, Adad-nirari III, Ashur-nirari V, Tiglath-Pileser III, Shalmaneser V. A few Neo-Assyrian Emperors—eg Shalmaneser IV, Ashur-dan III—are less well-attested.

Emmet Sweeney

One of Heinsohn’s most active disciples is the Scottish historian Emmet Sweeney. While Sweeney accepts the broad thrust of Heinsohn’s model, he has modified it considerably, so that many of Heinsohn’s parallels have been altered. For example, Sweeney has eliminated the Middle Assyrian Empire, regarding its rulers as simply duplicates of the Kings of Mitanni. He has also identified the earliest of the Neo-Assyrians with Median Emperors, while still retaining Heinsohn’s Mitanni = Media equation. Furthermore, he has rejected Heinsohn’s identification of the Persians with the Old Babylonians, seeing the latter as a Scythian dynasty that ruled Babylonia in the 7th century BCE. Finally, he identifies the Neo-Babylonians with the later Persian Emperors.

It need hardly be repeated that the Classical historians knew nothing of a Middle or Neo-Assyrian Empire. As far as they were concerned, there was only one Assyrian Empire—the one which modern historians call the old Assyrian Empire.

Sweeney’s chronology is summarized in the following table:

| BCE | Assyrians & Babylonians | Medes & Persians |

|---|---|---|

| 600 | Shalmaneser III | Cyaxares II |

| 568 | Shamshi-Adad IV | Arbaces |

| 564 | Adad-nirari III | Astyages |

| 550 | Tukulti-Ninurta II = Tiglath-Pileser III | Cyrus II the Great |

| 530 | Shalmaneser V | Cambyses II |

| 522 | Sargon II | Darius I the Great |

| 486 | Sennacherib | Xerxes I |

| 450 | Esarhaddon | Artaxerxes I |

| 424 | Sin-nadin-apli | Xerxes II |

| 424 | Ashurbanipal | Darius II |

| 404 | Nabopolassar | Artaxerxes II |

| 358 | Nebuchadnezzar II | Artaxerxes III |

| 336 | Nergilissar | Arses (Artaxerxes IV) |

| 336 | Nabonidus | Darius III |

Sweeney identifies Adad-nirari I with the Mitannian King Artatama I and [Adad-nirari III] with Astyages, the last Emperor of the Medes (Sweeney 125). He does not mention any Adad-nirari II. The numbering of ancient rulers is a modern convention, so it is often not clear how many different monarchs bore the same royal name, or to which of them a particular artifact is to be ascribed.

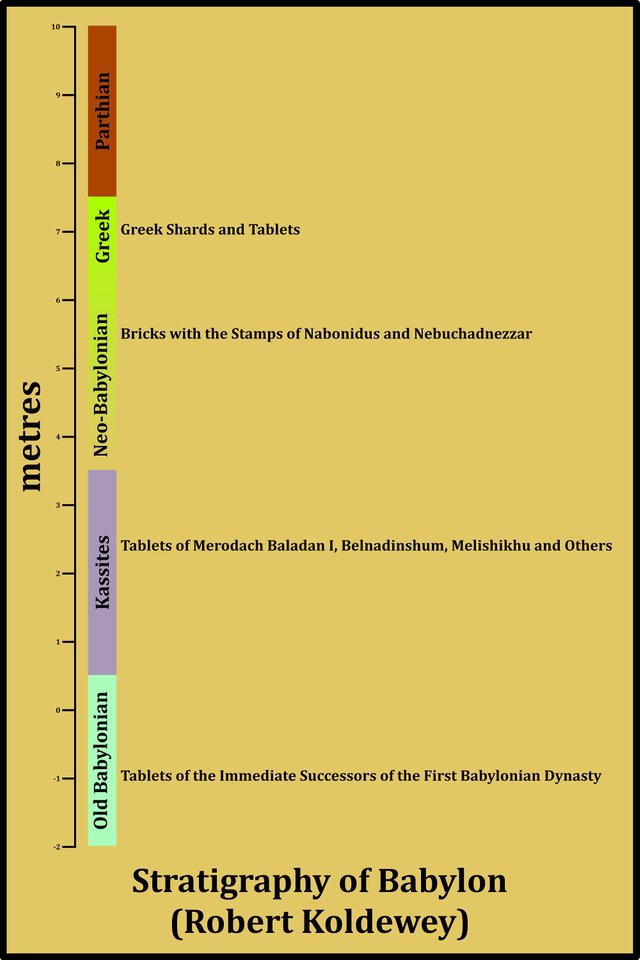

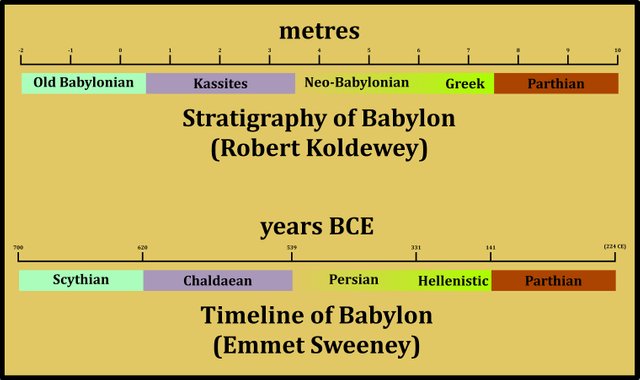

Heinsohn identified the Persians with the Old Babylonians because the latter were Amorites, and Heinsohn believed that Amorite was the same as Amardi, the name of one of the Persian tribes from which the Achaemenid Empire emerged (Heinsohn 2007:28, 47 ff). In an earlier article, however, we saw that the Babylonian stratigraphy, uncovered in 1914 by the German archaeologist Robert Koldewey, had the Neo-Babylonian stratum above the Old Babylonians and Kassites and below the Hellenistic layer:

By identifying the Old Babylonians with the Persians, Heinsohn has broken his own dictum: “Stratigraphy trumps all.” Sweeney has corrected this error:

I would scarcely consider it important to mention the Old Babylonians here, since they belong to an age earlier than that examined in the present volume, were it not for the fact that my colleague Gunnar Heinsohn has repeatedly identified them as alter-egos of the Persians. Thus for example he sees Hammurabi, who promulgated a famous table of laws, as an alter-ego of Darius the Great, who was reputedly the first king to produce a written legal code.

Whilst over the years I have generally been in agreement with Heinsohn, on this crucial identification I part company with him.

The true historical position of the Old Babylonians is revealed in the stratigraphy of Babylon. Here, as seen earlier in the present chapter, Robert Koldewey discovered evidence of these kings at the very bottom-most layer of the city, occurring at one meter below zero and immediately underneath the earliest of the Kassites. The Kassites were contemporaries of the Egyptian Eighteenth and Nineteenth Dynasties, a fact confirmed in innumerable ways and doubted by no one. It was a well-known Kassite king, Burnaburiash, who sent a series of petulant missives to Amenhotep III and Akhnaton.

Before taking another step, we should note here that were we to equate the Old Babylonians (coming before the Kassites), with the Persians, then we must as a consequence place the Kassites, as well as the Egyptian Eighteenth and Nineteenth Dynasties, after the Persians. This alone, in and of itself, completely refutes the equation of Old Babylonians and Persians. (Sweeney 188-189)

A Good Fit?

How good a fit is Sweeney’s model? There are places where the sequence of Median and Persian Emperors seems to line up well with the corresponding sequence of Mitannian and Assyrian Emperors. For example, the first five rulers of the Persian Empire do appear to repeat the pattern of the five Neo-Assyrian Emperors from Tiglath-Pileser III to Esarhaddon

| Neo-Assyrians | Persians |

|---|---|

| Tiglath-Pileser III | Cyrus the Great |

| Shalmaneser V | Cambyses |

| Sargon II | Darius the Great |

| Sennacherib | Xerxes I |

| Esarhaddon | Artaxerxes I |

Tiglath-Pileser III and Cyrus the Great were both great reformers and conquerors. Their lineages are obscure and still matters of scholarly dispute. Both were usurpers, claiming the throne following a successful revolt. Tiglath-Pileser reigned as Emperor for about eighteen years. Cyrus’ reign from his defeat of Astyages the Mede at the Battle of Pasargadae lasted about nineteen years.

Each was succeeded by a son: Shalmaneser V and Cambyses II. The former reigned for five years, the latter for eight. Both rulers were succeeded by usurpers, who established new Dynasties. The precise circumstances of their deaths are unknown.

Darius is alleged to have reigned for thirty-six years, considerably longer than Sargon’s seventeen. Sweeney does not address this discrepancy. There is also the matter of Bardiya or Smerdis, Cambyses’ younger brother, who is alleged to have held the throne for a few months before he was deposed by Darius. According to some accounts, this ephemeral figure was actually a magus called Gaumata, who personated Bardiya. There is no comparable figure in the Neo-Assyrian line of succession, but the circumstances surrounding the death of Shalmaneser V and Sargon’s rise to power are too unclear to rule anything out.

Sargon and Darius were succeeded by their sons, Sennacherib and Xerxes I respectively. Sennacherib reigned for twenty-four years, Xerxes for twenty-one.

Sennacherib and Xerxes were succeeded by their sons, Esarhaddon and Artaxerxes I. There is, however, a large discrepancy between the lengths of their reigns. Esarhaddon only reigned for about twelve years, while Artaxerxes’ reign lasted no less than forty-one years. Sweeney argues that the latter figure records the length of Artaxerxes’ life, not his reign (Sweeney 138, 184 ff).

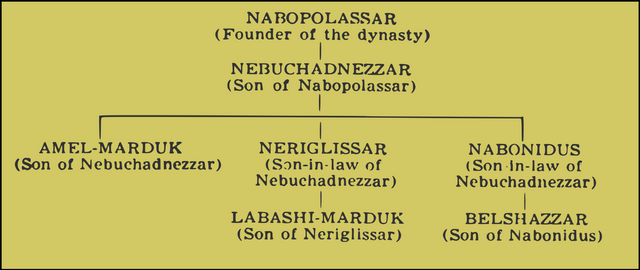

Sweeney’s hypothesis that the Neo-Babylonian Emperors were the last of the Persian Emperors is another interesting refinement of Heinsohn’s model. According to this new model, Nabopolassar, the founder of the Neo-Babylonian Empire was Artaxerxes II:

After the death of Ashurbanipal the Neo-Assyrian kingdom was rent with civil discord. It was in the midst of this strife that Babylon was re-established as the true center of power in the Fertile Crescent. One son of the Great King, a man named Sin-shar-ishkun, inherited the throne of Assyria proper; but he was immediately opposed by Nabopolassar, the king of Babylon and apparently a relative of the former. A record of the great conflict which followed is preserved in a number of cuneiform documents, documents of course normally held to date from the latter 7th century. We hold however that these texts tell of the war of succession waged between Artaxerxes II and his brother Cyrus the Younger upon the death of Darius II. (Sweeney 145)

Sweeney does not explain how or when Nineveh came to be sacked and abandoned by the Persians. Nineveh was already a ruin when Xenophon participated in the war between Artaxerxes and Cyrus (Anabasis ). Xenophon does state explicitly that the Persians took Nineveh from the Medes. According to the conventional chronology, the city was sacked and abandoned at the very beginning of the Median Empire. To this mainstream historians reply that Xenophon was simply wrong.

It is unrealistic to expect there to be a perfect correlation between Persian and Assyrian records. The reign-length of the King of Persia need not be the same as that of the King of Assyria, even if they are one and the same person. One reign may be dated from a coronation in Susa or Persepolis, the other from a separate coronation in Nineveh or Babylon. And because news took several months to spread across the vast empire, it would not be unusual for the reign of a particular king to continue long past his actual death. There is also the tricky question of co-regencies to be considered.

Another point to be taken into account is the curious fact that while we know where every one of the Persian Emperors is buried, the tombs of the Neo-Assyrian Emperors have never been discovered. This is an embarrassing state of affairs for mainstream archaeologists, and it is usually just ignored. Is it not strange that we know where the remains of several of the Neo-Assyrian Emperors’ consorts lie buried, but not any of the Emperors themselves?

But these are matters that we will return to in later articles.

Conclusions

In general, I find myself in broad agreement with Emmet Sweeney’s revised model. But, as usual, the devil is in the detail, and many of the details do not fit neatly into Sweeney’s model as it currently stands. There is still much work to be done in this field.

And that’s a good place to stop.

References

- Gunnar Heinsohn, Catastrophism, Revisionism, and Velikovsky, in Lewis M Greenberg (editor), Kronos: A Journal of Interdisciplinary Synthesis, Volume 11, Number 1, Kronos Press, Deerfield Beach, FL (1985)

- Gunnar Heinsohn, The Restoration of Ancient History, Mikamar Publishing, Portland, OR (1994)

- Gunnar Heinsohn, Die Sumerer gab es nicht [The Sumerians Never Existed], Mantis Verlag, Gräfelfing, Munich (2007)

- Gunnar Heinsohn, Heribert Illig, Wann lebten die Pharaonen? [When Did the Pharaohs Live?], Eichborn Verlag, Frankfurt (1990)

- Gunnar Heinsohn, M Eichborn, Wie alt ist das Menschengeschlecht? [How Old Is Mankind?], Mantis Verlag, Gräfelfing, Munich (1996)

- Robert Koldewey, The Excavations at Babylon, Translated by Agnes S Johns, Macmillan and Co, Limited, London (1914)

- Daniel David Luckenbill, Ancient Records of Assyria and Bablyonia, Volume 1, The University of Chicago Press, Chicago (1926)

- Emmet Sweeney, The Ramessides, Medes, and Persians, Ages in Alignment, Volume 4, Algora Publishing, New York (2008)

- Immanuel Velikovsky, Ramses II and His Time, Paradigma, Online (2010)

- Immanuel Velikovsky, The Assyrian Conquest, The Immanuel Velikovsky Archive, Online (1999)

Image Credits

- Administrative Structure of the Persian Empire (490 BCE): © Ian Mladjov, Fair Use

- Gunnar Heinsohn: © Freud (photographer), Creative Commons License

- Die Sumerer gab es night: © Heribert Illig (designer), Pierre Amiet et al, Handbuch der Formen- und Stilkunde: Antike, Wiesbaden (1988), Page 130

- Emmet Sweeney: © Society for Interdisciplinary Studies (SIS), Fair Use

- The Achaemenid Family Tree: © पाटलिपुत्र, Creative Commons License

- The Neo-Babylonian Dynasty: © Raymond Philip Dougherty, Nabonidus and Belshazzar, Page 79, Yale Oriental Series, Yale University Press, New Haven, CT 1929(1929) Fair Use

Online Resources