The Restoration of Ancient History is a paper delivered in November 1994 by Gunnar Heinsohn, Professor Emeritus at the University of Bremen in Germany, at a symposium in Portland, Oregon. This paper questions the conventional chronology of ancient history and offers in its place a radical reconstruction—the so-called Short Chronology, of which Heinsohn is the principal architect. In this series of articles, we are taking a closer look at the evidence cited in this paper in favour of Heinsohn’s new chronology:

Part 3 of Heinsohn’s lecture is entitled: Archaeologically-missing history and historically-unexpected archaeology in major areas of antiquity.. In this section, Heinsohn reviews a long list of cases where archaeologists have discovered major discrepancies between the archaeology of the Ancient World and its history as recorded by the Classical historians. These discrepancies fall into two broad categories:

Excavations in which the archaeologists failed to find strata that the recorded history had led them to expect.

Excavations in which the archaeologists uncovered strata that did not correspond to any cultures or civilizations in the recorded history.

In this article we will be examining Heinsohn’s chronology of the so-called Indus Valley Civilization and seeing how he fits this mysterious culture into the recorded history of the Ancient World.

The Indus Valley Civilization

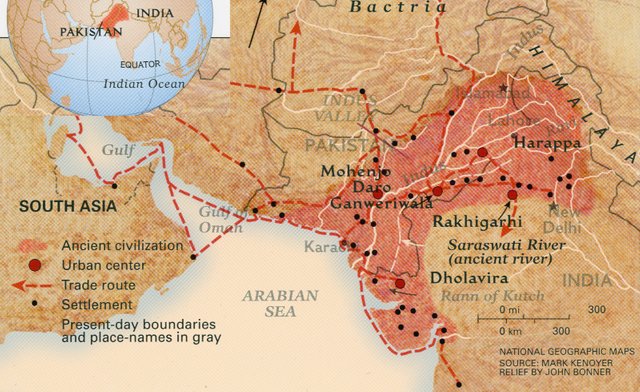

According to conventional archaeology, the Indus Valley Civilization was a Bronze Age civilization roughly contemporaneous with the Bronze Age civilizations of ancient Egypt and Mesopotamia. It was the most extensive of the three, but its heartland was centred on the basins of the River Indus and its former tributary the Sarasvati:

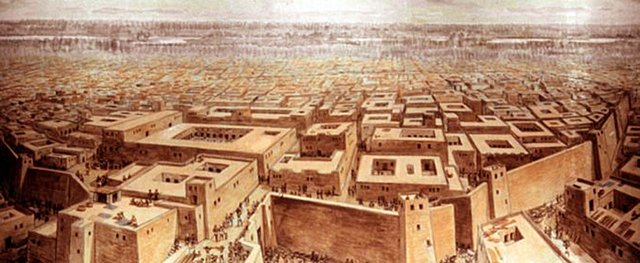

In the third millennium this civilization flourished over an area far larger than those of its contemporaries in Mesopotamia and Egypt. But while both of the latter continued to evolve in the second millennium, the Indus civilization disintegrated ... While the civilizations of Egypt, Mesopotamia, and China left enduring monuments and historical records and were remembered in later times, the Indus civilization was forgotten. Thus, when the European antiquarians began to investigate Asia’s past in the late eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, only the later traces of India’s ancient history commanded their attention ... The discovery of the Indus civilization in the 1920s, when excavations began at Mohenjo-daro and Harappa, therefore took Europe by storm. The cities’ well laid-out streets and fine houses with bathrooms surprised and impressed archaeologists and the public alike, while the discovery of seals bearing an enigmatic script intrigued them. The contemporaneity of the Indus cities with Mesopotamia’s civilization was quickly established. Excavations by Sir Mortimer Wheeler in the 1940s brought further publicity. (McIntosh 4)

The origins of the Indus Valley Civilization—also known as the Harappan Civilization after one of its cities—and its place in the wider history of the Indian subcontinent are still matters of scholarly debate:

Though much is now known about the Indus civilization, the failure to decipher the script has left many questions unanswered, including the very identity of the Indus people. Uniquely among all the ancient and more recent civilizations, it appears to have developed and thrived without warfare or violent competition, either internally or externally. There are no palaces, and very few structures can be identified as having had a religious function; yet the civilization seems to have been highly organized, with good-quality artifacts widely distributed, even in villages. Its merchants traded Harappan products over a vast area, from Central Asia to Mesopotamia, and yet almost nothing is known of what they brought home. And, after six or seven centuries, urban life suddenly collapsed, a process whose reasons are still hotly debated, not least because of the controversy over the arrival of the speakers of the Indo-Aryan languages that now dominate the subcontinent, a subject that stirs up deep partisan feelings among some scholars. (McIntosh 4-6)

According to the conventional chronology, civilization arose in the Indus Valley around the same time as it did in southern Mesopotamia, and both regions shared several characteristic traits:

Urbanization: The building of large, sophisticated cities of mud brick over a wide area.

Agriculture: The development of large-scale agricultural projects, possibly with extensive irrigation and flood control.

Writing: The evolution of protoscripts that would later evolve into fully-fledged writing systems.

Riverine: Both civilizations grew up on the banks of great rivers. This was also the case in ancient Egypt and China. The fertility of floodplains and the abundant supply of water for irrigation made these river basins ideal for the large-scale agriculture that supported these early civilizations. Artificial irrigation was practised on a large scale in Mesopotamia, but in Egypt the flooding of the Nile irrigated the crops, and in the Indus Valley flooding and rainfall were sufficient to allow agriculture to flourish.

The conventional timeline of the Indus Valley Civilization may be briefly tabulated. As usual, the timeline is arranged from bottom to top, in the manner of archaeological strata:

| BCE | Period | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 1900-1300 | Late Harappan | Disintegration and Final Collapse |

| 2000-1900 | Late Mature Harappan | Decline, Sarasvati Dries Up |

| 2500-2000 | Mature Harappan | Cultural High Point |

| 2600-2500 | Transitional Harappan | Collapse and Resurgence, Writing |

| 3200-2600 | Early Harappan | First Cities, Irrigation, Protoscript |

(McIntosh 419-422)

It is clear that something dramatic occurred in the Indus Valley during the Transitional Harappan, which conventional archaeologists date to 2600-2500 BCE. McIntosh summarizes this century in the following words:

Many settlements in the plains destroyed or abandoned, some rebuilt, many new settlements founded, probably including Mohenjo-daro; cultural integration; growing craft specialization; emergence of writing. (McIntosh 421)

Do these events imply that Early Harappan state was conquered and colonized by foreign invaders? Or were these dramatic changes purely internal matters? Is it significant that this Transitional period was immediately followed by the golden age of the Indus Valley Civilization, which McIntosh summarizes thus:

Cultural unity in Indus plains from Gujarat to northern Ganges-Yamuna doab; separate but related Kulli culture in southern Baluchistan; separate Late Kot-Diji culture in northern Indo-Iranian borderlands; well integrated internal distribution network; external trade with neighbors, Gulf and northern Afghanistan where Shortugai is founded; towns and cities; writing; craft specialization and industrial villages. (McIntosh 421)

The changes that occurred during the Transitional Harappan remain unexplained:

An understanding of how and why these changes took place is still elusive. (McIntosh 82)

Who Were the Harappans?

When I first learnt of the Indus-Valley Civilization in school more than forty years ago, it was given an alternative name in my textbook: Dravidian. This referred to the popular idea that the Harappans were of the same stock as the pre-Indo-Aryan inhabitants of the Indian Deccan:

The inhabitants of south India were found to be speakers of non-Indo-European languages, dubbed Dravidian by Robert Caldwell. (McIntosh 28)

Since the Indus Valley Civilization had supposedly risen and fallen centuries before the rise of the Indo-European Vedic Civilization of India, it was natural to suppose that its citizens spoke a pre-Indo-European language:

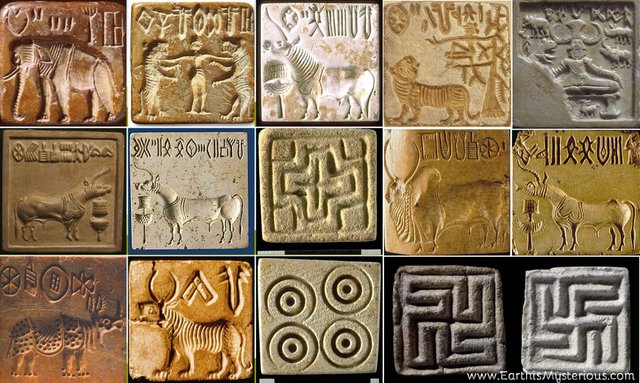

The short inscriptions on the Indus seals and on a few copper bars from Mohenjo-daro that Banerji at first compared to Indian punch-marked coins attracted considerable interest, and an attempt at decipherment of the script was made as early as 1925, by Colonel L. A. Waddell. In the years that followed, further efforts were made, based on comparisons between Indus signs and those of the Sumerian, Minoan, Etruscan, Hittite, and Brahmi scripts, and even Easter Island rongo-rongo. None produced a successful result. A question of key importance in decipherment of the script was what language it rendered: Marshall was of the opinion that the languages spoken in the Indus civilization were likely to have been members of the Dravidian family. (McIntosh )

This opinion has proved to be remarkably persistent, despite the fact that there is actually very little evidence to support it.

Graham Hancock was one of the first researchers to suggest that the creators of the Indus Valley Civilization were the original speakers of Sanskrit. Far from advocating the sort of realignment of Harappan civilization envisaged by Heinsohn, Hancock sees it as even older than mainstream archaeologists assert:

Hypothesis: The Indus-Sarasvati civilization, the development of which archaeologists have already traced back 9000 years, has an earlier episode of hidden prehistory. It was founded by the survivors of a lost Indian coastal civilization destroyed by the great global floods at the end of the Ice Age ... The survivors who established the early villages practised a ‘proto-Vedic’ religion that they had brought with them from their inundated homeland and probably spoke an early form of Sanskrit. (Underworld 206)

If we accept the conventional chronology, however, this would imply that Proto-Indo-European had already given rise to Sanskrit several millennia earlier than seems credible:

While it is possible that a few speakers of Proto-Indo-Iranian traveled to the Indus region during the third millennium, linguistic history firmly rules out any suggestion that an Indo-Aryan language was spoken by the Harappans. Furthermore, the Indo-Aryan texts reflect a society very different from that of the urban Indus civilization—small warlike groups of pastoral nomads to whom the domestic horse was supremely important; there were no horses in the subcontinent in the Harappan period. (McIntosh 350)

This is a reasonable position to hold if one accepts the conventional chronology, which firmly places the Harappans in the remote pre-Indo-European era. If, however, the Harappan civilization arose much later than is conventionally thought, then the possibility that the Harappans were the original speakers of Sanskrit has to be taken seriously.

Heinsohn’s Model

Heinsohn’s realignment of the Indus Valley Civilization is compared with the conventional chronology in the following table:

| Conventional | Conventional | Heinsohn | Heinsohn |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1900-1300 | Late Harappan | Persian Satrapy | 520-330 |

| 2000-1900 | Late Mature Harappan | Median India | 630-520 |

| 2500-2000 | Mature Harappan | Assyrian India | 750-630 |

| 3200-2500 | Early & Transitional Harappan | Early India | 1150-750 |

Prior to the Persian conquest, the Indus Valley Civilization was an independent polity according to Heinsohn. It lay on the eastern border of the Empire of the Medes between 630 and 520 BCE. Curiously, Heinsohn also says that it lay on the eastern border of Ninos’s Assyrian Empire between 750 and 630 BCE. There is, however, no evidence that the Assyrian Empire ever reached as far as India. In fact, there is no evidence that the Assyrian Empire ever extended beyond the Zagros Mountains.

Note that Heinsohn does not distinguish between Early Harappan and Transitional Harappan. In his paper, he refers to the period 1150-750 BCE as the Amri-Period. This refers to the Amri-Nal Culture, an Early Harappan culture in Sind Province and Baluchistan (McIntosh 420). It is named for two Harappan cities, Amri and Nal, which are in Sind and Baluchistan respectively.

Twentieth Satrapy

According to Heinsohn, the final phase of the Indus Valley Civilization corresponds to the twentieth satrapy of the Achaemenid (Persian) Empire. In The Histories, Herodotus tells us that Darius I divided his empire into twenty provinces called satrapies. The twentieth of these was in India, and paid the largest tribute of all the satrapies:

94 ... The Indians made up the twentieth province. These are more in number than any nation known to me, and they paid a greater tribute than any other province, namely three hundred and sixty talents of gold dust. 95 Now if these Babylonian silver talents be reckoned in Euboïc money, the sum is seen to be nine thousand eight hundred and eighty Euboïc talents: and the gold coin being counted as thirteen times the value of the silver, the gold-dust is found to be of the worth of four thousand six hundred and eighty Euboïc talents. Therefore it is seen by adding all together that Darius collected a yearly tribute of fourteen thousand five hundred and sixty talents; I take no account of figures less than ten. (Godley 123)

The Satrapy of India, therefore, contributed almost one third of the revenue of the entire Empire.

Herodotus’s description of the Indians, however, does not seem to bear out Heinsohn’s claim that this satrapy corresponded to the final phase of the Indus Valley Civilization. The latter was a highly urbanized state, comprising dozens of populous, well-built cities. This does not accord with Herodotus’s description:

98 ... There are many Indian nations, none speaking the same language; some of them are nomads, some not; some dwell in the river marshes and live on raw fish, which they catch from reed boats ... 99 Other Indians, to the east of these, are nomads and eat raw flesh; they are called Padaei ... 100 There are other Indians, again, who kill no living creature, nor sow, nor are wont to have houses; they eat grass, and they have a grain growing naturally from the earth in its husk, about the size of a millet-seed, which they gather with the husk and boil and eat ... 101 These Indians of whom I speak have intercourse openly like cattle; they are all black-skinned, like the Ethiopians. Their genital seed too is not white like other men’s, but black like their skin, and resembles in this respect that of the Ethiopians. These Indians dwell far away from the Persians southwards, and were no subjects of King Darius. (Godley 127-129)

Furthermore, the enormous quantities of gold-dust which India poured annually into the Persian treasury were not the profits of a lively trade. This gold was extracted from auriferous sand, harvested from a desert to the north of the satrapy:

98 All this abundance of gold, whence the Indians send the aforesaid gold-dust to the king, they win in such manner as I will show ... 102 Other Indians dwell near the town of Caspatyrus and the Pactyic country, northward of the rest of India; these live like the Bactrians; they are of all Indians the most warlike, and it is they who are charged with the getting of the gold; for in these parts all is desert by reason of the sand. There are found in this sandy desert ants not so big as dogs but bigger than foxes; the Persian king has some of these, which have been caught there. These ants make their dwellings underground, digging out the sand in the same manner as do the ants in Greece, to which they are very like in shape, and the sand which they carry forth from the holes is full of gold. It is for this sand that the Indians set forth into the desert. (Godley 127-131)

Caspatyrus is otherwise unknown. It is thought to lie somewhere in the vicinity of Peshawar, or in the catchment area of the Kabul River, a tributary of the Indus. It is the only Indian city mentioned by Herodotus. From Herodotus’s account, it appears that the Harappan cities had already been abandoned by the time the Persians arrived.

Alexander the Great

When Alexander the Great traversed the Indus Valley in 327-326 BCE, the great civilization was no more. The military engineer Aristobulus of Cassandreia accompanied Alexander on his campaigns and wrote an account of all that he saw. This record is no longer extant, but several fragments survive and it was an important source for later scholars. Among these was Strabo, whose geography of India (Geographica, Book 15) is heavily indebted to Aristobulus. In the nineteenth chapter of this book, Strabo writes:

19: Aristobulus, comparing the characteristics of this country that are similar to those of both Egypt and Aethiopia. and again those that are opposite thereto, I mean the fact that the Nile is flooded from the southern rains, whereas the Indian rivers are flooded from the northern, inquires why the intermediate regions have no rainfall for neither the Thebais as far as Syene and the reason of Meroe nor the region of India from Patalene as far as the Hydaspes has any rain. But the country above these parts, in which both rain and snow fall, are cultivated, he says, in the same way as in the rest of the country that is outside India; for, he adds, it is watered by the rains and snows. And it is reasonable to suppose from his statements that the land is also quite subject to earthquakes, since it is made porous by reason of its great humidity and is subject to such fissures that even the beds of rivers are changed. At any rate, he says that when he was sent upon a certain mission he saw a country of more than a thousand cities, together with villages, that had been deserted because the Indus had abandoned its proper bed, and had turned aside into the other bed on the left that was much deeper, and flowed with precipitous descent like a cataract, so that the Indus no longer watered by its overflows the abandoned country on the right, since that country was now above the level, not only of the new stream, but also of its overflows. (Strabo)

These abandoned cities were surely the ruins of the Harappan cities. But if these had really been abandoned around 1300 BCE, would they still have been visible above ground a thousand years later? Aristobulus was clearly describing cities that had only recently been abandoned. He believed that they had been abandoned because changes in the course of the Indus meant that the land could no longer be irrigated. But the lack of precipitation in the area between Patalene (ie Sind, near the mouth of the Indus) and the Hydaspes (ie the Jhelum River in the Punjab) may also have been a crucial factor.

Ginenthal’s Model

Heinsohn’s reconstruction of the chronology of the Indus Valley Civilization is not the only model espoused by adherents of the Short Chronology. Charles Ginenthal has proposed an alternative timeline which places the rise of urbanization around 1300 BCE but dates the Late Harappan to approximately 750-700 BCE. Ginenthal believes that a dramatic change in climate—Klimasturz—around 800 BCE led to the dramatic collapse of the Harappan Civilization. Something similar also occurred in Lower Mesopotamia and eventually led to the abandonment of the Chaldaean (ie Sumerian) cities of the region, but here the situation was complicated by a process known as salinization.

Ginenthal believes that the Harappan Civilization collapsed shortly after 800 BCE because the rainfall which had allowed agriculture to thrive in the Indus Valley for several centuries disappeared. Salinization, which played a significant role in Lower Mesopotamia, was not an issue, as irrigation was not practised in the Indus Valley:

“Irrigation not only alters the water balance by bringing in more water, it also brings in more salts. Whether taken from a river or pumped from the groundwater, even the best quality freshwater contains some dissolved salts. . . . The amount of salt brought in with the water may seem negligible, but the amounts of water applied over the course of time are huge.” [Nyle C. Brady, Ray R. Weil, The Nature and Properties of Soil, 13th ed. (Upper Saddle River NJ 2002), p. 421] (Ginenthal 2003:363)

In Lower Mesopotamia, where artificial irrigation was practised on a large scale, oversalinization of the soil eventually led to the abandonment of the famous cities of Ur, Eridu, Uruk, Kish, etc. In the Plain of Shinar (Sumeria, or Chaldaea) the water table was close to the surface, so this salt became concentrated in the upper layers of soil. Further north, in Babylonia and Assyria, the water table lay much deeper beneath the surface, so it took considerably longer for salinization to adversely affect the fertility of the soil. But even here, oversalinization was achieved in Abbasid times (750-1258 CE).

In Egypt, on the other hand, the annual flooding of the Nile helped to leach the salt out of the soil, because the Nile remained below the level of the fields, keeping the water table low enough to allow agriculture to flourish continuously for thousands of years.

But what of the Indus Valley?

In ancient Mesopotamia and in parts of South Asia in historical and recent times, regular irrigation over a prolonged period caused salinization, eventually turning land into a salt waste where cultivation became increasingly difficult and eventually impossible. Although this cycle would also have taken place in the ancient Indus Valley if artificial irrigation had been employed, there is no evidence from the Indus period either of large-scale irrigation or of salinization there: The annual river floods and limited rainfall seem to have been adequate to support agriculture in the plains. (McIntosh 23-24)

Ginenthal believes that prior to the Late Mature Harappan, there was actually little flooding of the rivers, and agriculture flourished only because there was a significant amount of annual precipitation—much more than there is today (Ginenthal 2008:542-549). But around 800 BCE this all changed. The rainfall migrated northwards. The Indus Valley was transformed from a moist fertile plain into a desert, and the rainfall in the far northern highlands led to annual flooding, which the Harappans could not control. They had no experience with large-scale irrigation, as they had never had any need for it. In Lower Mesopotamia, however, irrigation had been practised for centuries, so they were able to cope with the disastrous drop in precipitation until salinization became a problem.

Ginenthal sums of his case thus:

Both civilizations [Lower Mesopotamia and the Indus Valley] shared very similar climates at the same time and therefore, when the Harappans had abundant rainfall, so too did the Mesopotamians! Given that trade in certain goods ties these civilizations together in time, and all the scientific/technological evidence indicates that the chronology of Mesopotamia is no older than 1300 B.C., Harappan civilization can be no older than Mesopotamian civilization. The great cities on the southern Babylonian plain are abandoned during the Persian era, perhaps 50 to 75 years before the coming of Alexander the Great, because of irrigation salinization of the soil. That requires that about 400 years earlier the southern Babylonian plain had a climate shift which had to have occurred around 800 to 750 B.C. which allowed only irrigation agriculture to continue there for about 400 years. The climate shift for the Harappan civilization had to occur at the same time as in Mesopotamia. In this way both civilizations down to about 800-750 B.C. had rainfall to grow crops and thereafter Mesopotamia developed irrigation which the Harappans never did.

There was irrigation in Mesopotamia prior to 800 B.C. because there is evidence for it in the Uruk period which we place in the mid to latter part of the second millennium. But because of the greater rainfall the Tigris and Euphrates rivers flowed much more rapidly and the Mesopotamians did not build levees. Therefore the water table as in ancient Egypt would only rise during the summer season and any canals or irrigation ditches dug from these rivers would only fill during this time. However, when the river levels fell, so too would the water table, so that irrigating the land would flush away the salts as it did in Egypt. The Egyptians have irrigated their land for thousands of years, but because the river level falls, so too does the water table with it, and thus they had no problem with salinization. Until around 800-750 B.C. a very similar process occurred in southern Mesopotamia.

Thereafter, with that climate shift, the amount of rainfall on Mesopotamia and its northern mountain ranges diminished. The rivers flowed more slowly, levees were built up and with the rivers raised above the plain, water constantly kept seeping from them down into the soil, raising the water table. Irrigation became a necessity with less rainfall, and gradually the soil began to become poisoned with salt. None of the processes just described are contrary to the rules of science, agronomy, or climatology.

The evidence in this unit precludes that the Sumerian/Chaldean or Harappan civilizations could have existed in the late third to the early second millennium B.C. There is no scientific or technological evidence to support the thesis that these civilizations existed then; but there is clear-cut scientific and technological evidence that they existed in the first millennium B.C. As with the evidence that the civilizations were placed in the early to late second millennium B.C. by the historians and archaeologists, no such forensic historical evidence is known for their existence at the earlier period, either. (Ginenthal 2008:549-550)

I find this scenario more convincing than Heinsohn’s. Ginenthal’s timeline for the Harappan Civilization might be interpolated as in the following table. Note, though, that he only explicitly dates its rise to c 1300 BCE, and its decline to the period 800-750 BCE:

| BCE | Period |

|---|---|

| 750-700 | Late Harappan |

| 800-750 | Late Mature Harappan |

| 1000-800 | Mature Harappan |

| 1200-1000 | Transitional Harappan |

| 1300-1200 | Early Harappan |

According to my hypothesis, when the Indus Valley Civilization collapsed, the Harappans were forced to emigrate out of the Indus Valley in large numbers. Some of these migrated east into India, where they established the Vedic Civilization. Others went west in search of new homes. Of the latter, some settled to the east of the Zagros Mountains: these were the Medes of the Classical historians. Others crossed the Zagros and settled in northern Mesopotamia: these were the Mitannians.

And what happened during the Transitional Harappan? That is still a mystery. One possibility is that the Early Harappans were indeed Dravidians, as the mainstream archaeologists surmise, but that the Indus Valley was subsequently invaded and overrun by Sanskrit-speaking Indo-Aryans during the Transitional period. But this is just speculation on my part. Neither Heinsohn nor Ginenthal has anything to say about this Transitional period. Nor does Heinsohn explain why, in his opinion, the Harappan Civilization collapsed shortly before the arrival of Alexander the Great.

And that’s a good place to stop.

References

- Charles Ginenthal, Pillars of the Past, Volume 1, Forest Hills, NY (2003)

- Charles Ginenthal, Pillars of the Past, Volume 2, Forest Hills, NY (2008)

- Alfred Denis Godley (translator), Herodotus, Volume 2, The Histories, Books 3-4, Loeb Classical Library, William Heinemann, London (1928)

- Graham Hancock, Underworld: The Mysterious Origins of Civilization, Three Rivers Press, New York (2003)

- Gunnar Heinsohn, Catastrophism, Revisionism, and Velikovsky, in Lewis M Greenberg (editor), Kronos: A Journal of Interdisciplinary Synthesis, Volume 11, Number 1, Kronos Press, Deerfield Beach, FL (1985)

- Gunnar Heinsohn, The Restoration of Ancient History, Mikamar Publishing, Portland, OR (1994)

- Gunnar Heinsohn, Die Sumerer gab es nicht [The Sumerians Never Existed], Frankfurt (1988)

- Gunnar Heinsohn, Heribert Illig, Wann lebten die Pharaonen? [When Did the Pharaohs Live?], Eichborn Verlag, Frankfurt (1990)

- Gunnar Heinsohn, M Eichborn, Wie alt ist das Menschengeschlecht? [How Old Is Mankind?], Mantis Verlag, Gräfelfing, Munich (1996)

- Jane R McIntosh, The Ancient Indus Valley: New Perspectives, ABC-CLIO, Santa Barbara, CA (2008)

Image Credits

- Indus Valley Civilization: Mark Kenoyer and John Bonner (designers), © National Geographic Society, Fair Use

- Ruins of the Harappan City of Mohenjo-daro: James P Blair (photographer), © National Geographic Society, Fair Use

- The Granary and Great Hall on Mound F in Harappa: © Muhammad Bin Naveed, Creative Commons License

- Seals from the Indus Valley Civilization: © Earth is Mysterious, Fair Use

- Graham Hancock: © Cpt.Muji, Creative Commons License

- Administrative Structure of the Persian Empire (490 BCE): © Ian Mladjov, Fair Use

- Desert Landscape in Kuz Kunar (Afghanistan): © Hawza Khan, Fair Use

- Alexander and Porus: Charles Le Brun (artist), Musée du Louvre, Paris, Public Domain

- Charles Ginenthal: © Dwardu Cardona, Fair Use

- Rice Fields on the Banks of the Indus: © Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc, Fair Use

- Artist’s Impression of Mohenjo-daro: © University of Minnesota, Fair Use

Online Resources