The Restoration of Ancient History is a paper delivered in November 1994 by Gunnar Heinsohn, Professor Emeritus at the University of Bremen in Germany, at a symposium in Portland, Oregon. This paper questions the conventional chronology of ancient history and offers in its place a radical reconstruction—the so-called Short Chronology, of which Heinsohn is the principal architect. In this series of articles, we are taking a closer look at the evidence cited in this paper in favour of Heinsohn’s new chronology.

In this article we will continue our study of Part 2 of Heinsohn’s lecture: The sequence of ancient empires with the center in Assyria as it was taught by Greek historians since the time of Hekateios (-560/550 to -500/494).. Here Heinsohn is concerned primarily with Upper Mesopotamia—the region centred on the River Tigris and known to Classical historians as Assyria.

Based on these accounts, Heinsohn recognizes four periods in the history of Assyria before Alexander the Great:

| Years BCE | Regime |

|---|---|

| 1150-750 | Early Assyrians |

| 750-620 | Assyrian Empire |

| 620-540 | Empire of the Medes |

| 540-330 | Persian Empire |

In the last article, we looked at the archaeology of Assyria and saw that it does not bear out the history of Assyria as recorded by the Classical historians Herodotus, Ctesias, and their successors. These historians, we learnt, were in broad agreement that Assyria had once formed the nucleus of three successive empires—Assyrians, Medes, and Persians—prior to the conquests of Alexander the Great. There may also have been a brief period during the Empire of the Medes when the Scythians were the dominant nation in Mesopotamia. In this article, we are going to turn our attention to Lower Mesopotamia—Southern Mesopotamia, Chaldaea, or Babylonia—and see whether the archaeology of Babylon fares any better:

According to Diodoros (II: lff.), Ninos conquered Chaldaea (Southern Mesopotamia/Babylonia) ... Around -610, under their king Cyaxares [the Medes] eventually “made the Assyrians their subjects, except for the province of Babylon” (The History I: 106). Babylonia was regained by the Chaldaeans with whom the Medes had to share the spoils of Ninos’ empire. (Heinsohn)

Based on the accounts of the Classical historians, Heinsohn recognizes four periods in the history of Babylonia before Alexander the Great:

| Years BCE | Regime |

|---|---|

| 1150-750 | Chaldaeans |

| 750-620 | Assyrian Empire |

| 620-540 | Chaldaeans |

| 540-330 | Persian Empire |

Excavating Babylon

The first scientific excavations were carried out at Babylon between 1899 and 1917 by a team from the German Oriental Society led by the archaeologist Robert Koldewey.

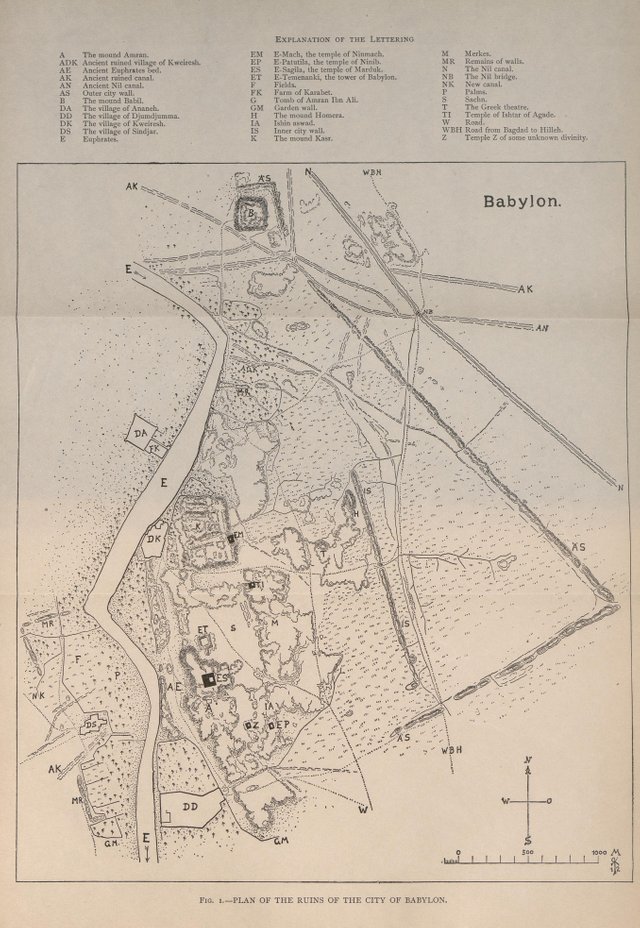

In Chapter 42, Koldewey describes the results of the excavation of a series of mounds in the northeast of the city, close to the Temple of Ninmah. This dig, which was begun in the autumn of 1908, uncovered the stratigraphy of the ancient city. In 1913, while these excavations were still in progress, Koldewey brought out his classic account of the work under the German title Das wieder erstehende Babylon [Babylon Resurrected]. In 1914, this was translated into English by Agnes S Johns as The Excavations at Babylon:

Merkes, which means a city as a trade centre in distinction to a village, is the name given by the Arabs to the line of mounds to the north of Ishin aswad (Fig. 155). Here the houses of the citizens of Babylon are easier of access than in the lower quarters of the town. They occupy in different levels, one above another, the entire mass of the hill, which rises to 10 metres above zero. Our excavations cut through the layers down to a depth of 12 metres below the surface, where the water-level stopped farther progress, although the ruins themselves continued lower. Thus the water must now stand at a higher level than in ancient times.

As it did not seem advisable to accumulate great masses of rubbish in the vicinity where occupied town area was everywhere to be expected, we worked over the site with a system of pits 7 metres square, with gangways between them 3 metres wide. Thus when the first pit had been sunk completely to water-level the earth from the next one could be thrown into it, thus avoiding any possible damage to the ruins, for the upper layers at any rate had to be removed in order to reach the lower ones. I need not say that all the walls, graves, and separate finds were recorded in the drawings and sections we made of the site.

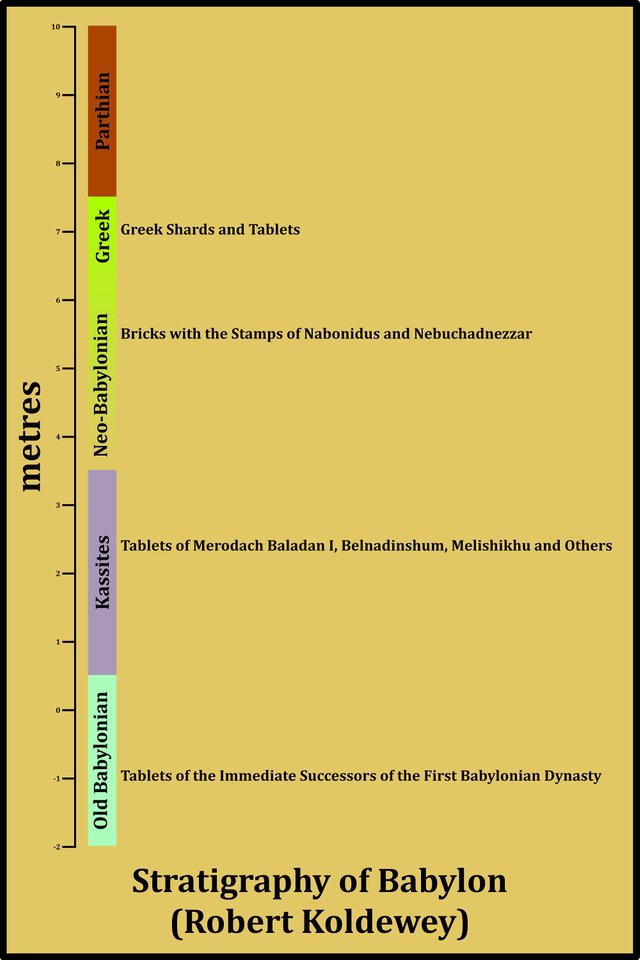

In the 2 to 3 upper metres lay the scanty ruins of the Parthian period, thin house walls of mud brick or of brick rubble, with wide spaces between them, which may be regarded as gardens or waste land.

The 4 metres below this represent the brilliant time of the city under the Neo-Babylonian kings on into the Persian and Greek periods. The houses are closely crowded together in the narrow streets. There was little open ground, and what was at first a court or the garden of a house was increasingly required for house building. It was at this time that the population was richest and most numerous. The houses have strong walls of mud brick, good brick floorings, and numerous circular wells and sunk shafts, which bear witness to the comparatively high level of the requirements demanded by the culture of that time. Greek sherds and tablets with dates of the Persian period lay at the height of 7 metres above zero, and bricks with the stamps of Nabonidus and Nebuchadnezzar at 5.5 metres.

Below, the signs of dwellings are again more scanty until the level of 2.4 above zero is reached, when there are once more thick house walls similar to those of the Neo-Babylonian level, though at wider distances apart. At this level there were tablets with the dates of Merodach-Baladan, Belnadinshum, Melishikhu, and others. Thus the stratum dates from about 1300 to 1400 b.c.

Deeper down the strata were irregular. Here they do not lie throughout in one solid uniform line. At 1 metre below zero we came once more on a uniform, clearly-marked stratum with houses lying rather closely together, in which were found tablets with dates of the time of the first Babylonian kings, the immediate successors of Hammurabi (2250 b.c.), Samsuiluna, Ammiditana, Samsu-ditana, etc. The mud-brick walls of the houses are not very thick, but all of them rest on a foundation of burnt brick. They show numerous traces of a conflagration in which they were destroyed. The tablets lay among these undisturbed ashes, so there can be no doubt that they were contemporary (see section on Fig. 237).

This is a bare outline of the find in the north of Merkes. If we dig farther in the plain, we find the Nebuchadnezzar stratum nearer the surface, and the Hammurabi stratum disappears below water-level. This means undoubtedly that as far back as the latter period the town level here was rising in the form of a mound, and that at the Parthian period no substantial buildings stood in the plain. (Koldewey 239-242)

The most notable thing about this stratigraphy is the complete absence of a stratum for the Persian period. Koldewey carried out this excavation with the expectation that the Persian stratum would lie below the Greek layer and above the Neo-Babylonian layer. After all, that is what the conventional history would leads one to expect:

The Neo-Babylonians (Nabopolassar, Nebuchadnezzar II ... Nabonidus) ruled Babylon for 87 years, from 626 to 539 BCE.

The Persians ruled the city for 208 years, from 539 to 331 BCE.

The Greek or Hellenistic period lasted for about 181 years, from 331 to 150 BCE, when the Parthians conquered Babylonia.

But beneath the stratum with Greek sherds and tablets was the Neo-Babylonian stratum: the Persian stratum was missing, even though it ought to have been the thickest. Rather than reassess the conventional timeline, Koldewey simply assigned the stratum above the Neo-Babylonian layer to both the Persians and the Greeks, even though the material in it was clearly Greek. This is not how science is supposed to work. The model should be adjusted to fit the data—not the other way round. Sadly, this sort of thing is all too common in modern archaeology. As we saw in the previous article, archaeologists will bend over backwards to fit the data to their preconceived models.

Below the Neo-Babylonian stratum, Koldewey uncovered a stratum with material dating to the Kassite period (Merodach-Baladan I, Belnadinshum and Melishikhu were late Kassite rulers of Babylon), and below this he found a stratum dating back to the Old Babylonian period—the First Dynasty of Babylon, which included among its rulers Hammurabi, Samsuiluna, Ammiditana, and Samsu-ditana, and their immediate successors.

In his 1994 lecture, Heinsohn does not actually mention Koldewey’s Babylonian stratigraphy. Perhaps he was unaware of it at the time.

In the next article in this series, we will proceed to Part 3 of the lecture, in which Heinsohn catalogues the innumerable discrepancies between the archaeology of the Ancient East and its recorded history.

To be continued ...

References

- Gunnar Heinsohn, Catastrophism, Revisionism, and Velikovsky, in Lewis M Greenberg (editor), Kronos: A Journal of Interdisciplinary Synthesis, Volume 11, Number 1, Kronos Press, Deerfield Beach, FL (1985)

- Gunnar Heinsohn, The Restoration of Ancient History, Mikamar Publishing, Portland, OR (1994)

- Gunnar Heinsohn, Die Sumerer gab es nicht [The Sumerians Never Existed], Frankfurt (1988)

- Gunnar Heinsohn, Heribert Illig, Wann lebten die Pharaonen? [When Did the Pharaohs Live?], Eichborn Verlag, Frankfurt (1990)

- Gunnar Heinsohn, M Eichborn, Wie alt ist das Menschengeschlecht? [How Old Is Mankind?], Mantis Verlag, Gräfelfing, Munich (1996)

- Robert Koldewey, Das wieder erstehende Babylon, J C Hinrichs, Leipzig (1913)

- Robert Koldewey, The Excavations at Babylon, Translated by Agnes S Johns, Macmillan and Co, Limited, London (1914)

Image Credits

- Babylon: © Aziz1005, Creative Commons License

- Map of Babylon: © Micro, Creative Commons License

- Robert Koldewey: Gertrude Bell (photographer), Koldewey-Nachlass, Vorderasiatisches Museum Berlin, Public Domain

- Plan of the Ruins of Babylon: Robert Koldewey, The Excavations at Babylon, Figure 1, Public Domain

Online Resources