In the last article in this series, we saw that the orthodox history of the Hittites was seriously flawed. The archaeology of Anatolia was at odds with what the Classical historians had written about this region. If the conventional or mainstream opinion is incorrect, then who were the Hittites? Independent researchers have come up with several different answers to this question, and in this article we will examine a few of them.

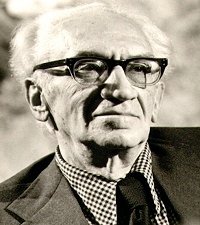

Immanuel Velikovsky

The Russian catastrophist Immanuel Velikovsky argued that the Hittites were the Chaldaeans or Neo-Babylonians of 626-539 BCE. Velikovsky had noted that Classical historians recorded the existence of “Chaldians” in northeastern Anatolia:

Xenophon, the Athenian soldier (ca. -435 to -335) who fought in the army of Cyrus the Younger of Persia and traversed with the famous “ten thousand” mercenaries the length of Asia Minor, wrote about the Chaldeans as a tribe living in Armenia that stretched from Ararat to south of the Black Sea. One hundred forty years earlier Cyrus the Great, at war with Croesus, referred to Chaldeans as “neighbors” of Armenians. He also said of the land which modern scholars assign to the Hittites: “These mountains which we see belong to Chaldaea.” Strabo, a native of Amasia in Pontus, who knew Asia Minor at first hand, located the Chaldeans next to Trapezus (Trebizond) on the Black Sea coast: “Above the region of Pharnacia and Trapezus are the Tibareni and the Chaldaei, whose country extends to lesser Armenia” It is asserted that these “Black Sea Chaldeans” of Xenophon and Strabo are not the real Chaldeans but “Chaldians,” or that Xenophon used the wrong name for the bellicose tribe of that region. But Xenophon and Strabo were not wrong. Though under Nabopolassar and Nebuchadnezzar the Chaldeans entered the melting pot of the Neo-Babylonian Empire, many of them survived in Cappadocia: Xenophon met them there at the close of the fifth century and Strabo records their presence in the area as late as the first. (Velikovsky 111)

Velikovsky went on to argue that the Hittite Emperor Hattusilis III was none other than Nebuchadnezzar II, the “Chaldaean” King of Babylon. This hypothesis has generally been abandoned by Velikovsky’s disciples. Gunnar Heinsohn, Emmet Sweeney, Charles Ginenthal and Lynn E Rose all identify the Chaldaeans with the Sumerians of Lower Mesopotamia. Furthermore, Sweeney has identified the Neo-Babylonian Emperors Nabopolassar, Nebuchadnezzar II, Neriglissar, and Nabonidus with the late Persian Emperors Artaxerxes II, Artaxerxes III, Arses, and Darius III respectively.

The Hittite Empire had been dated mainly with the help of synchronisms with Egypt, whereas the Syro-Hittite states relied on Neo-Assyrian synchronisms. Velikovsky rejected the conventional Egyptian chronology but accepted for the most part the conventional Neo-Assyrian chronology. Consequently, he was led to argue that the Syro-Hittite states had preceded—not followed—the Hittite Empire. Many of Velikovsky’s disciples, however, are as critical of the Neo-Assyrian chronology as they are of the Egyptian chronology. His identification of the Hittites and the Chaldaeans has generally been rejected by modern Velikovskians.

Roger Waite

Like Velikovsky, the independent researcher Roger Waite accepts the conventional chronology of the Neo-Assyrian Empire, but is dissatisfied with that of Egypt. He has summarized the problems of the imperial Hittite archaeology and history as follows:

The New Hittite Empire art of the Anatolia shows signs of Assyrian influence of the 7th and 6th centuries.

The Styles of writing used in the annals is similar to the style of 7th century Assyrian kings.

Legal proceedings have Assyrian equivalents in the 7th century.

Scientific knowledge reflects the world of the Assyrian and Babylonian cultures of the 8th to 6th centuries.

Weaponry in the Hittite sculptures reflects the royal weaponry of the 7th century.

Pottery of the 7th century occurs in New Hittite Empire strata.

Anatolian stratigraphic dates and chronology contradict the historical placement of the Hittite empire.

The history contained in the imperial Hittite annals of Mursilis II reflect Assyrian power that is 8th century or later.

Hittite sites in Anatolia lack occupation between 1200 and 750 BC.

The Neo-Hittite sites do not exhibit characteristics of offspring of an Imperial Hittite

influence. (Waite 1240-1241)

Waite concludes:

To fix the problems in Hittite history and archaeology, the events, art and strata that date to the thirteenth century must be moved to the seventh century. This requires that the treaty between Ramesses II and Hattusilis III be moved to the seventh century. Within the context of the Hittite material there is no Hittite chronology to offend and the Assyrian and Greek dates generally agree on this date. Within the Egyptian context this cannot be accomplished simply. Egyptologists are firm about placing Ramesses II in the 13th century. They are certain of their dates within 20 years just as the Assyriologists. There are no reigns of kings or dynasties that can be reduced by 700 years ... There is, however, one possible solution to the problem of reducing the date of the 19th Dynasty. That is to substitute it for the 26th Dynasty. This scheme assumes that the Manetho was confused about the dynastic order. Under this assumption he could have had two independent sources of information for the 26th Dynasty and may have listed the same dynasty twice so that the seventh century dynasty also appeared in the thirteenth century. Failing to recognize that the two sources spoke of the same dynasty, he created two dynasties. Indeed, this was the suggestion of Velikovsky [Velikovsky, 1978.] (Waite 1241 ... 1242)

The problem with Waite’s analysis is that it corrects Egyptian chronology while leaving the Neo-Assyrian chronology in place. But those of us who endorse the Short Chronology believe that the so-called Neo-Assyrian Empire was actually the Persian Empire—or, perhaps, the Median and the Persian Empires, as Emmet Sweeney argues. So, both chronologies must be moved forward by several centuries.

Curnock & Crowe

In The Hittites United, Barry Curnock and John Crowe begin by stating the conventional position:

According to our present understanding of ancient history there were two separate periods of Hittite civilisation. The first, called the Hittite Empire or Kingdom, based around Hattusas to the north of the Halys river, is roughly dated using Egyptian chronology, from c1700 to c1200 with some gaps. It was ended by the Sea Peoples, for whom we have little history and even less archaeology. Then after an absence of some two centuries, people with a very similar culture called the Neo-Hittites appear again, based in several cities in the region of northern Syria. They are dated from Assyrian chronology to c950 to c700. (Crowe 2)

The authors then argue that the true history of the Hittites comprised only one continuous period, which has been duplicated due to faulty chronology:

Given the multitude of archaeological problems caused by the gap between the two periods of Hittite history, the theory that they should be overlapped was first proposed by B S Curnock in an unpublished manuscript in 2007. More recently a Hittite study published by B S Curnock and P J Crowe (Crowe & Curnock) shows that nine major events found in the history of the Empire Hittites were apparently repeated, in the same order, in the history of the Neo-Hittites. The chances against this happening in two different periods of history are much too great to be dismissed as coincidence, and a further more detailed comparative study of the two eras was necessary. (Crowe 2)

Their findings:

reveal a single cohesive Hittite history of the first half of the first millennium BC. We believe we have demonstrated, beyond reasonable doubt, that the civilisation presently known as the Empire Hittites were the same people, with the same history, as those presently known as the Neo-Hittites. Their relations with neighbours such as Assyria, Babylon, Mitanni, Urartu, Phrygia and Lydia can now be understood within an integrated and more plausible historical context. (Crowe 2)

Their new chronology is as follows:

| Hittites | Dates |

|---|---|

| Hatti Old Kingdom | 950-820 |

| Hatti Middle Kingdom | 820-705 |

| Kaska Era | 705-675 |

| Hatti New Kingdom | 675-545 |

Among Curnock & Crowe’s claims, the following may be noted:

The Neo-Hittite state of Tabal refers to the Hittite heartland on the Anatolian Plateau, with its capital at Hattusas.

The period 820-740 was dominated by the rise of Mitanni. Like Roger Waite, they identify Mitanni with Urartu, in modern Armenia. In an earlier article, we saw that such an identification is at odds with the Short Chronology.

The Kaska were closely associated with the Cimmerians. In their paper, however, Crowe & Curnock do not clarify the identity of either of these nations. Were they Scythians? Were they one people known by two different names?

The city of Pteria, which Croesus King of Lydia sacked around 547 (Herodotus 1:76) was probably Hattusas.

Like Velikovsky and Waite, Curnock & Crowe accept the conventional chronology of the Neo-Assyrians, but not that of the Egyptians. Their synchronization of the Hittite Empire and the Syro-Hittite States, however, is worthy or consideration. It may be possible to square this hypothesis with the Short Chronology.

Sweeney’s Lydians

Emmet Sweeney is one of Gunnar Heinsohn’s busiest disciples. In his Ages in Alignment series, he has addressed the Hittite problem. His solution is quite radical: the ancient Hittites were the Lydians of the Classical historians:

During the time of the Eighteenth and Nineteenth Dynasties the greatest power in Anatolia was that of the Hittites, a people known to the Egyptians as Kheta or Khita. But the Hittites were in many respects reminiscent of the Lydians, the great power which, according to the classical authors, reigned over Anatolia between the 7th and 6th centuries BC. The “Hittite” language, known as Neshili, was in fact found to be virtually identical to that of the Lydians of the 6th century BC, 2 whilst their kings bore typically Lydian names such as Myrsilos (Mursilis) 3 and worshipped Lydian deities like Cybele (Kubaba). 4 In addition, the well-known enmity between the Hittites and Mitannians was strangely reminiscent of the Mede/Lydian rivalry referred to by classical authors like Herodotus. (Sweeney 9)

Elsewhere, Sweeney has argued that the “Hittite” ruler Hattusilis III and the Lydian king Alyattes were one and the same:

An examination of the lives and careers of the last two Hittite emperors, Hattusilis III and Tudkhaliash IV, reveals a close match with the lives and careers of the last two Lydian kings, Alyattes and Croesus. The Hittite Empire came crashing to destruction during the time of Tudkhaliash IV, and we find the “Assyrian” king Tukulti-Ninurta boasting of carrying off great numbers of Hittite prisoners. Since Tukulti-Ninurta was a contemporary of Ramses II and Merneptah, it follows that (if we credit Velikovsky’s own chronological measuring-rod and place these kings in the sixth century), Tukulti-Ninurta must be associated with Cyrus, the Persian conqueror of Lydia. As such, Hattusilis, who earlier waged a protracted war against Ramses II, must be the same person as Alyattes ... One final point. The name written in the cuneiform of Boghaz-koi [Hattusas] as Hattusilis is composed of two elements; Hattus-ili. Since vowels are conjectural and the order in which cuneiform syllables should be read by no means always certain, the same word could be written as Ali-hattus. In short, Hattusilis and Alyattes (Greek Aluattes) are the same name. (Hattusilis, King of Lydia)

This is certainly an ingenious solution to the problem of the silence of the Classical historians on the subject of the Hittites. But does it hold up to closer scrutiny? Croesus was the last King of Lydia, but Tudkhaliash IV was not the last king of the Hittites—two of his sons succeeded him, Arnuwanda III and Suppilumiuma II. And why would Tudkhaliash IV have sacked Hattusas, assuming Pteria and Hattusas refer to the same place? Simply equating the ancient Hittites and the Classical Lydians is too crude a solution. We must patiently unravel this Gordian Knot.

In Hittite records, Lydia is referred to as Seha River Land, a vassal state in the larger territory known as Arzawa (Bryce 51). Nevertheless, there was clearly a strong connection between the Hittites and the Lydians, and this should be explored.

Other revisionists—eg David Rohl and Peter James—have also shifted Egyptian chronology, which has affected Hittite history, but not as much as any of the foregoing scholars.

But what about Gunnar Heinsohn himself? Who does he say the Hittites were? That is what we will look at in the next article.

And that’s a good place to stop.

References

- Trevor Bryce, Warriors of Anatolia: A Concise History of the Hittites, I B Tauris & Co, Ltd, London (2019)

- P John Crowe & Barry S Curnock, The Neo-Hittites: A Case of Déjà Vu?, Chronology and Catastrophism Workshop, 2012:1 (February 2012), Society for Interdisciplinary Studies, Stopsley, Bedfordshire (2012)

- P John Crowe, The Hittites United, Online (2012)

- Gunnar Heinsohn, Catastrophism, Revisionism, and Velikovsky, in Lewis M Greenberg (editor), Kronos: A Journal of Interdisciplinary Synthesis, Volume 11, Number 1, Kronos Press, Deerfield Beach, FL (1985)

- Gunnar Heinsohn, The Restoration of Ancient History, Mikamar Publishing, Portland, OR (1994)

- Gunnar Heinsohn, Die Sumerer gab es nicht [The Sumerians Never Existed], Frankfurt (1988)

- Gunnar Heinsohn, Heribert Illig, Wann lebten die Pharaonen? [When Did the Pharaohs Live?], Eichborn Verlag, Frankfurt (1990)

- Gunnar Heinsohn, M Eichborn, Wie alt ist das Menschengeschlecht? [How Old Is Mankind?], Mantis Verlag, Gräfelfing, Munich (1996)

- Emmet John Sweeney, The Ramessides, Medes and Persians, Ages in Alignment, Volume 4, Algora Publishing, New York (2008)

- Immanuel Velikovsky, Ramses II and His Time, Paradigma, Online (2010)

- Roger Waite, The Chronology of Egypt and the Near East, Online

Image Credits

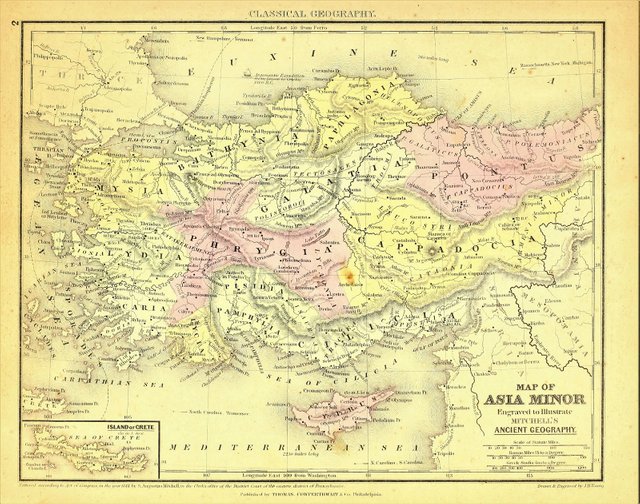

- Map of Asia Minor: Samuel Augustus Mitchell, Mitchell’s Ancient Atlas, Classical and Sacred, Thomas, Cowperthwait & Co, Philadelphia (1849), James Hamilton Young (engraver), Public Domain

- Immanuel Velikovsky: © Frederic Jueneman, Donna Foster Roizen (photographer), Creative Commons License

- Roger Waite: © Roger Waite, Fair Use

- Barry Curnock: Copyright Unknown, Fair Use

- Emmet Sweeney: © Society for Interdisciplinary Studies (SIS), Fair Use

Online Resources