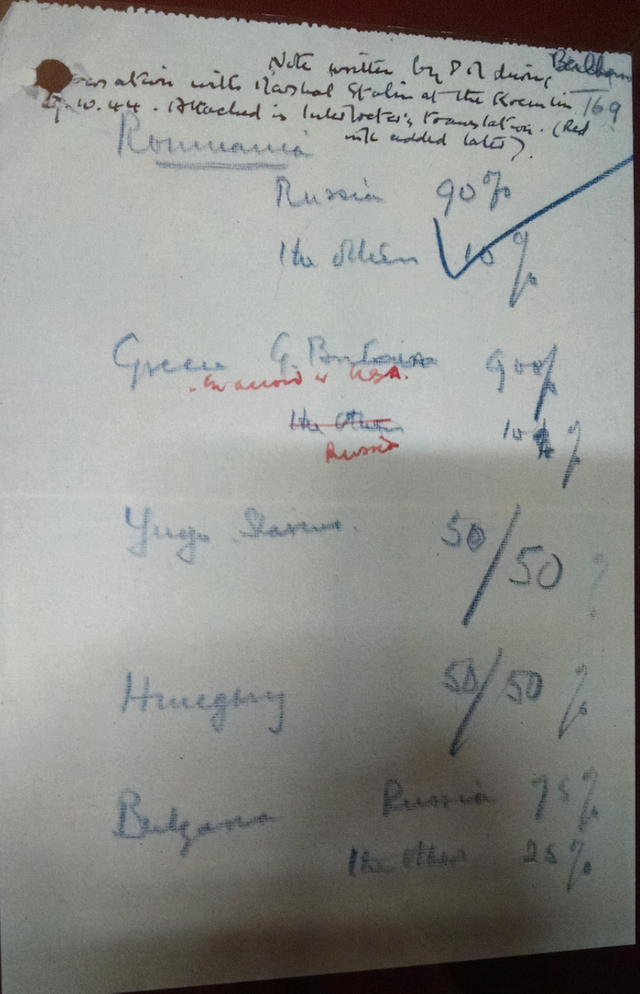

On October 9, 1944, just after “dusk crept over the sky from the […] horizon”1 British Prime Minister Winston Churchill and Soviet leader Joseph Stalin set down in one of the dark rooms of the Kremlin in Moscow, in order to discuss the future of Eastern-Europe. At this point in World War II, the Soviet Red Army had already liberated most of the motherland from German invaders, and occupied most of Romania and Bulgaria, as well as it was standing on the Eastern frontiers of Poland, Hungary and Slovakia with no intention to halt its Westward advance. One of the most memorable events of this otherwise 6 day long British-Soviet summits is the so-called “Percentage Agreement”, which both in the historiography and public memory is remembered as a document that divided Eastern European into Western and Soviet spheres of influence.

In this document, Churchill proposed an agreement to Stalin, one that would provision Western predominance in one sphere, and Soviet predominance in another sphere in the region. According to Churchill's account of the incident, he suggested that the Soviet Union should have 90% influence in Romania and 75% in Bulgaria (while the West would control 10% and 25% respectively); the United Kingdom should have 90% in Greece (a strategically crucial country for British imperial communications in the Mediterranean Sea); and the West and the Soviet Union should have shared 50-50% dominance both in Hungary and Yugoslavia. Churchill wrote this proposal on a piece of paper which he pushed across to Stalin, who ticked it off and passed it back. (Later, the percentages of Soviet influence in Bulgaria and Hungary were amended to 80%).

For a long period of time, the agreement was kept secret, and was only made officially public by Churchill twelve years later in 1956 in the final volume of his memoir. Since then, historians have written extensively about this infamous document, but interpretations were not able to fully disconnect from the ways Churchill presented it to the public. Although the document in itself suggests a crude, cynical and calculated great power attitude towards the fate of the region, until now, based on Churchill’s memoirs, the “Percentage Agreement” has been preserved in historical memory as Britain’s last ditch attempt to save Eastern Europe from Communism by attempting to secure some influence for the Western powers there.

Most historians consider the agreement to be deeply significant. In The Cambridge History of the Cold War, Norman Naimark writes that together with the Yalta and Potsdam agreements, “the notorious percentages agreement between Joseph Stalin and Winston Churchill […] confirmed that Eastern Europe, initially at least, would lie within the sphere of influence of the Soviet Union.”2 Similarly, in his acclaimed biography of Churchill, Roy Jenkins writes that the agreement “proposed Realpolitik spheres of influence in the Balkans”.3 Historian David Carlton has also notes that “a clear if informal deal had been done on the point that mattered most to Churchill: he had Stalin’s consent to handle Greece as he saw fit.” Churchill’s Foreign Secretary Anthony Eden wrote that months before the meeting, he and Churchill had discussed the issue and “we felt entitled to ask for Soviet support for our policy [with regard to Greece] in return for the support we were giving to Soviet policy with regard to Romania.”4

However, I tend to agree with historians, such as Gabriel Kolko and Geoffrey Roberts, who believed that the importance of the agreement was largely overrated.5 Crucially, new evidence, emerging from British archives suggest that until now we have completely misinterpreted the “Percentage Agreement” for which Churchill himself can be held responsible. British Cabinet documents covering Foreign Secretary Anthony Eden’s discussions with Soviet Minister of Foreign Affairs Vyacheslav Molotov clearly explain that the agreement was nothing more than Churchill’s and Stalin’s agreement on the number of delegates to be sent to the Allied Control Commissions after the war to the aforementioned countries.6

In his memoirs, Churchill went out of his way to explain that the agreement did not serve this purpose, but to save Eastern Europe from Soviet dominance, however, these new pieces of evidence clearly suggest that this was not the case and the document served less noble purposes. Significantly, these new archival documents put a dent in the myth that surrounded this piece of paper (and Churchill's alleged positive role in its creation), and confirm the absurdity of the notion that Churchill ever contemplated saving Eastern Europe from the Soviets in late 1944. While the document can be interpreted as a sphere of influence proposal for vital British interests, such as Greece, it certainly had very little to do with claiming any real post-war influence for the West in Eastern Europe. As Europe witnessed later, the British attempted to exert little influence in these Allied Control Commissions in Eastern European counties.

(the writing of a full-length article on the topic will follow shortly)

1, from John Steinbeck, The Grapes of Wrath.

2, Melvyn P. Leffler and Odd Arne Westad, eds., The Cambridge History of the Cold War, Vol. 1: Origins (Cambridge University Press, 2010), p. 175

3, Roy Jenkins, Churchill: A Biography (Macmillan, 2001), p. 759

4, David Carlton, Churchill and the Soviet Union (Manchester University Press, 2000) p. 114-116

5, Roberts, Geoffrey, Stalin's Wars: From World War to Cold War, 1939–1953. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, (2006), p. 218.

6, Since I am planning to write a full-length article about these newly emerged documents for a peer-reviewed journal, I do not wish to yet disclose the exact reference number of these official documents.

Congratulations @andras.becker! You received a personal award!

You can view your badges on your Steem Board and compare to others on the Steem Ranking

Vote for @Steemitboard as a witness to get one more award and increased upvotes!

Downvoting a post can decrease pending rewards and make it less visible. Common reasons:

Submit