Unlike the tomb of other Sultans or Kings in Aceh, this tomb was simple. This tomb did not have a tombstone.

There was only a plot of inscriptions that had curves resembling the head of a mihrab. This tomb also blended in well with the concrete built around the grave’s mound that where gravel and pebbles were placed as natural ornaments. Other than that, there were only two horizontal lines that acted as relief buildings.

The length of the tomb was approximately eight palms’ long. It had a width of four palms’ and was two inches high. Above the tomb, there were japanese grass. A jatropha tree fused into the green grass. Several new shoots could be seen on the trunk as well as on three branches the size of the little finger.

“Toeankoe Sulthan Mohammad Daoed Ibnalmarhoem Toeankoe Zainal Abidin Alaiddin Sjah. Wafat hari senen 6 Februari 1939.” That was the sentence written on the inscription, with Arabic-Jawi letters at the top and latin letters underneath.

Yes. This was the tomb of a king. Sultan Alaiddin Muhammad Daudsyah bin Tuanku Cut Zainal Abidin bin Sultan Alaiddin Mansursyah bin Sultan Alaiddin Jauhar Alamsyah bin Sultan Alaiddin Muhammadsyah Marhum Geudong – this was his full name based on his lineage. The last Sultan of the Kingdom of Aceh Darussalam.

I had the opportunity to visit his grave on a hot afternoon in late September 2016. The tomb of Sultan Muhammad Daudsyah was located at Utan Kayu General Cemetery, Rawamangun Muka Raya Street, Rawamangun Village, Pulo Gadung District, East Jakarta. The atmosphere of this cemetery complex was very different from the usual atmosphere of cemeteries in Aceh. Compared to the cemetery complex in Banda Aceh, like the Ulee Lheue mass grave complex which was quiet on most days, this funeral complex was the opposite.

From the gate, tombstones were neatly lined up by tall building located beside the cemetery. A bar of inscriptions was integrated into the concrete headstones that served as a nameplate. The white color of these tombs blended with the green japanese grass situated above all the graves, just like dandelions in the savana.

In front of the main gate, there was a line of flowers stalls. From here I walked on a road that divided the burial complex into two main sides. The Utan Kayu Cemetery Complex Service Office stood on the left side of the road, a dozen steps away from the gate.

“Well, there are no officers here because it is lunch hour. Try asking the men there. Maybe they know,” replied a man sitting in front of the office when I asked for the location of the Sultan’s tomb.

I continued walking. The trees lining the two sides of the road shaded me from the sun. The wind blew slowly. There was a scent coming from the mound of red earth void of a headstone. It was the scent of flowers sprinkled all over the new cemetery, two blocks from the right side of the road. Along the way I encountered several people selling meatballs, siomay, coffee, and mineral water. There were children running around.

Several men were sitting in the shelter under the trees, with shovels in front of or beside them. There were several middle-aged men dressed in religious garbs. After taking a few steps from the office earlier, one of them greeted me with a slightly forced smile.

“Want to visit your family’s grave, sir? Do you want me to pray for your family?”

I politely refused and ask for the location of the Sultan’s grave.

“Sir, just walk straight. After three hundred meters, look to the right side of the road. You will see it. The grave is different from the others. It is easy to find,” he said, pointing with the tip of his thumb.

I continued walking until another middle-aged man came to greet me. This guy was friendly. His name is Sodiq. He claimed that he came from Bogor and had been working in this cemetery complex since 1985 as a grave-digger. He enthusiastically offered to escort me after saying he wanted to visit the Sultan’s tomb.

According to this man from Bogor, people who visit the tomb are diverse. Some come with an angkot, others ride the ojek. There are also people who come in expensive cars. But as he recalled, those who frequently visit the grave are the Sultan’s descendants. Their faces are recognizable.

“To my knowledge, in these two to three months, you are the only visitor,” he said.

The Utan Kayu Cemetery Complex is under the management of Parks and Cemetery Agency of Jakarta Capital Special Region. Its total land area is 6.6 hectares. Inside, there are 20,657 graves divided into 4 blocks, where each block is subdivided into 37 plots. In one plot there are approximately 500 graves. The tomb of the Sultan Muhammad Daudsyah is located in Block A-II, plot 35.

In that plot, the Sultan’s tomb is in the second row. In addition to the Sultan’s tomb, there are dozens of other graves of Acehnese aristocrats in this plot. All of these graves surround the Sultan’s tomb. In the first row, the graves bear the names of Teuku Abdullah bin Teuku M. Djalil and Pocut Nuraimah binti Teuku Keumangan Pocut Umar. These two graves are located in front of the Sultan’s tomb. Tuginem’s grave is located on his left side and Kabil Widagdo’s grave is located on his right.

In the second row, in addition to the tomb of the Sultan there are four other graves. Three on the left side, and one on the right. Their names are Teuku Muhammad Daud bin Pangleh, Tuanku Mahmud bin Tuanku Abdul Madjid, Teuku Chiek Ali Basyah. On the right side of the Sultan’s tomb is Tgk. Putih binti Tuanku Zainal Abidin bin Sultan Alaiddin Ibrahim Mansursyah’s grave. Behind the Sultan’s tomb there are three other graves. One of them is Hj. Cut Nur Asiah binti Teuku Radja Sabi’s.

What distinguishes the tomb of Sultan Muhammad Daudsyah from most of the graves here is that it is taller. It is also more spacious on the right side. There is enough space for visitors to sit.

The head of the Utan Kayu Cemetery Service Office, Irfan Al Akram, who I had met after, said that he did not know much about the tomb. He had just started working here.

Being in the tomb of Sultan Muhammad Daudsyah is just like re-reading Aceh’s history, especially the history of the Aceh War against the Dutch collonial invaders. The length of his tomb is less than a meter that holds a great narrative of the endless struggle of the Aceh warriors. And Sultan Muhammad Daudsyah is a symbol of the relentless resistance of the people.

Tuanku Muhammad Daudsyah was appointed Sultan on January 28, 1874. The Dutch launched the first aggression into Aceh in March 1873. Then, the Sultan was seven years old. He was crowned by royal officials in an emergency. The war had just begun.

He was the Sultan who never relaxed in Taman Gairah (Gairah Park). He never performed ablution or washed his feet in Krueng Daroy (Daroy River), what more sit on the throne of Istana Dalam, from where his predecessors had govern the farthest land, from Muko-muko on the west coast to Rengat in the east of Sumatera island, from Kedah to Pahang on the Malacca peninsula.

“After reaching puberty, Sultan Muhammad Daudsyah began to hold the reins of government. Keumala Dalam was chosen to be the base of the government after Koetaradja and most of Aceh Rayeuk was invaded by the Dutch. It became the place where he launched the struggle against the Dutch,” said Tuanku Warul.

Tuanku Warul is one of the great grandchildren of the Sultan, the son of Tuanku Yusuf bin Tuanku Ibrahim bin Sultan Muhammad Daudsyah. He enthusiastically shared his great-grandfather’s story one afternoon in mid-October 2016, at his residence on Jalan Pang Lateh, Merduati, Banda Aceh.

According to him, the presence of the Sultan Muhammad Daudsyah in Keumala Dalam became a motivation for the people of Aceh to continue fighting against the Dutch colonial invaders. The Ulee Balang (aristocrats of Aceh) who had previously submitted to the Dutch returned to the Sultan and pledged to continue the struggle. This made the Dutch troops try desperately to catch the Sultan, until on November 26, 1902, the Dutch troops kidnapped one of the wives of the Sultan, Pocut Putroe.

But the Sultan did not surrender and continued his resistance with his loyal followers. Because of this, the empress of another Sultan, Pocut Murong was also kidnapped, together with the prince Tuanku Ibrahim on December 25, 1902. This shows how the Dutch colonials completely lost their minds over the ‘stubbornness’ of Sultan Muhammad Daudsyah.

His stubbornness (read: determination) is the reason why his grave is not in Kandang XII, not in Kandang Meuh or in the tomb complex of other Aceh kings, but in a public cemetery in Jakarta City. Approxmately 1557 miles from his native land.

It was the ultimatum of the Dutch—either surrender for the family’s salvation or continue to wage war and get his family members killed—which made Sultan eventually put his rencong back in the sheath. After agreeing with the royal officials and the leaders of the struggle, the Sultan descended from his stronghold, on Saturday, January 10, 1903.

Tuanku Warul argued that Sultan Muhammad Daudsyah’s surrender does not mean that the struggle instantly ended.

“He understood the situation. When the Dutch cheated by holding the empress and the crown prince captive, the Sultan faced the Dutch as a commoner, not as the Sultan of the Kingdom of Aceh Darussalam that was being conquered,” said Tuanku Warul.

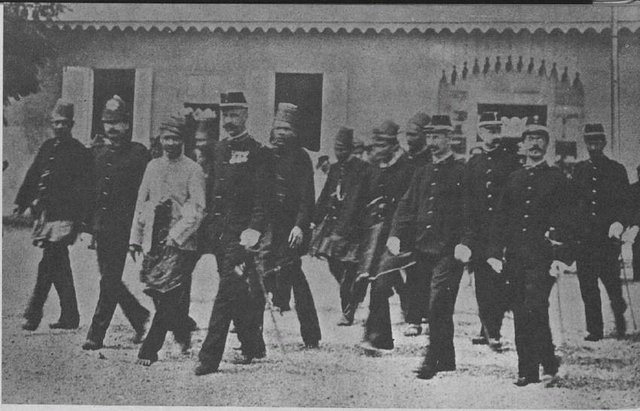

This can be proven by a photograph contained in the history books of the Aceh War. When the Sultan arrived at Sigli, he was wearing simple clothes without any footwear. Did he not own any sandals or shoes?

On the other hand the fact that he never invited the royal officials to join the Dutch side shows that he did not give up as the royal chief. He was acting as the head of the household who wanted to save his family members.

The surrender to the Dutch side did not mean that the struggle had ended. On the contrary, despite being placed in Kutaradja under Dutch supervision, Sultan Muhammad Daudsyah remained in touch with the fighters. He contributed the salary he received from the colonial government to the cost of the struggle.

He used the news of Japan winning the war with Russia in 1905 as a moment to establish relationships and ask for help through his letters. These actions later led Van Daalen to send a letter to Governor-General Van Heutz in Batavia as mentioned in the book Aceh Sepanjang Abad, written by Mohammad Said.

“... From the letters, it was clear that Sultan Muhammad Daudsyah hoped that the Japanese would bring some of his warships here with the intention of attacking us from the sea, while he from his side drove the little pigs (the Dutch) from land.”

This was why the Dutch was suspicious of his activities – even though he had surrendered, he still performed subversive acts. On Wednesday afternoon January 21, August 1907 Sultan Muhammad Daudsyah was forcibly sent to Batavia with family members and some of his followers. On August 30 of the same year he was examined by the Betawi resident, J. Hofland, in front of the assistant resident L. J. F. Rijckmans who took the Sultan to Batavia. There were many subversive allegations. On December 24, 1907, the Dutch East Indies government threw the Sultan to Ambon.

After ten years of exile, in 1917 Sultan Muhammad Daudsyah was allowed to choose one of his residences in the Dutch East Indies, except in Sumatera. The Sultan chose Batavia as his residence until February 6, 1939. He died there, and was buried in a plot of land which is now TPU Utan Kayu Pulo Gadung, East Jakarta.

“One issue that should be highlighted is that Sultan Muhammad Daudsyah never went to sign the treaty of the conquest of the Kingdom of Aceh Darussalam by the Dutch goverment. His determination was the main ingredient in establishing the sovereignty of Indonesia during the era of independence. But unfortunately, not many are paying attention to this issue,” Tuanku Warul said at the end of the conversation.

After talking to Tuanku Warul, I was reminded of the tomb of Sultan Muhammad Daudsyah in ‘exile’, far from his native land, far away from the memory of the people of Aceh now. In Banda Aceh the name of Sultan Muhammad Daudsyah is only used as a name of a road in Peunayong. It stretches eight shopping blocks, has a base around the Babul Zamzam Mosque and ends on Jalan Khairil Anwar. According to Google maps, the length of the road is only 600 meters, not any longer than that.[]

Downvoting a post can decrease pending rewards and make it less visible. Common reasons:

Submit

Thank you @tomahawk429

Downvoting a post can decrease pending rewards and make it less visible. Common reasons:

Submit

Downvoting a post can decrease pending rewards and make it less visible. Common reasons:

Submit

oman hana power

Downvoting a post can decrease pending rewards and make it less visible. Common reasons:

Submit

Hana masalah bg @siagamz

Setidak jih na hi ramee yg vote. Hehe

Downvoting a post can decrease pending rewards and make it less visible. Common reasons:

Submit

Bereh

Downvoting a post can decrease pending rewards and make it less visible. Common reasons:

Submit

Teurimong geunaseh @steemwart

Downvoting a post can decrease pending rewards and make it less visible. Common reasons:

Submit

We must not forget history, to a dignified aceh.

Downvoting a post can decrease pending rewards and make it less visible. Common reasons:

Submit

Exactly bg @jufrisalam. As such as Hasan Tiro said, "Soe mantong nyang peuteuwoe seudjarah. Meumakna ka dipeulamiet droe bak gob."

Downvoting a post can decrease pending rewards and make it less visible. Common reasons:

Submit

This is awe-inspiring.

Downvoting a post can decrease pending rewards and make it less visible. Common reasons:

Submit