Precursor to the Mỹ Lai Massacre: 1968 Phong Nhị, Phong Nhất_21: Inspired by Alain Delon

By early April of 1968, the soldiers from Korea were exhausted from the warm and humid weather typical in Southeast Asia. The 1st Company of the 1st Squadron of the 2nd Brigade of the Marine Corps (Blue Dragon Unit) was on a search and inspection mission with a 2nd rank of marching troops. They rotated being the advance guard, and that day, it was the first platoon’s turn, led by Lieutenant Choi. The advance guards always had to be more alert because they would likely be the first to face the enemy's attack. About an hour had passed when the senior sergeant in the front squad stopped the troops. He approached Lieutenant Choi and pointed to a small forest ahead, saying "I don’t have a good feeling about this. It feels like something's going to pop out at any moment, don’t you think?" With the dense reed-like grasses shooting up above human height, it did in fact feel ominous, as if a sniper might be hiding within. Entering the forest in a search attempt would be dangerous, but they couldn’t just ignore it altogether either. There was, however, a perfect trick for a time like this.

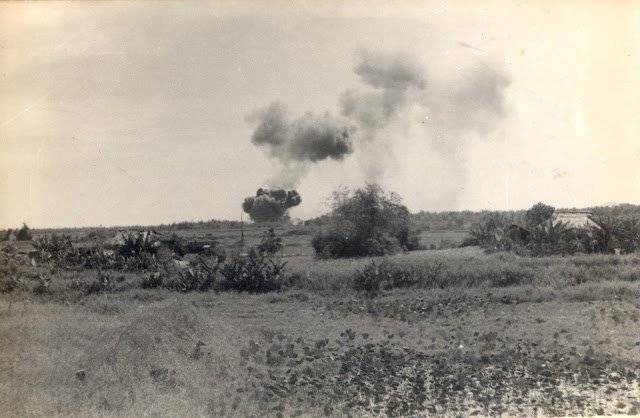

The very sound that resonated day and night near the villages of Phong Nhị and Phong Nhất. At the request of the 1st company, the artillery battallion's curved shells hit the ground, creating a huge explosion cloud. Photography by Choi Young Un

Lieutenant Choi orchestrated an operation. The squad leader brought him a carbine gun with which he struck three or four shots into the air behind the captain. It was totally different from the sound of an M16. Immediately, radio messages were received from captain Eun Myung-soo. "What was that just now?" “There must be enemies ahead.” “Really?” “I believe we should request artillery support.” "Alright. Call the coordinates." Lieutenant Choi looked at the battle map and accurately pinpointed the target. Perhaps the captain had also noticed something strange. Either way, there was no harm in playing along, since they would have something to show for to the battalion and brigade headquarters. This would then call it a day.

Bombs went off overhead. The soldiers, including Lieutenant Choi Young-un, covered their ears. Shortly after, there was a series of explosive sounds, similar to the sound of gunshots at the start of a race. Boom! Boom! Boom! Boom! The bombs flew every minute and hit their target several times. A small forest, some 200 meters ahead, was completely devastated as a result. If there were any living creature there, there would be no chance it could make it out alive. A 155mm curved cannon was fired from an artillery battalion in Hoi An, as a result of Choi’s report and the ensuing request for support from his captain. The bomb flew more than 10 kilometers and brutally destroyed a point in the jungle, west of the Điện Bàn district in Quang Nam Province. There was silence after the shelling stopped. Only smoke continued to rise from the forest ahead. Somebody exclaimed in a smug tone of voice, "Serves them right."

The enemy's bombs were horrifying, but the ally’s bombs were like an exciting game. Listening to the sound of consecutive bombings relieved the soldiers’ stress and put them in better moods, even if they knew this was just 'kara,' a commonly used term in the military which means, "fake" in Japanese. They felt a great degree of excitement that day, even if they knew that they were just acting out a screenplay wherein a 155-millimeter shell is fired through the radio reporting system.

The battalion would submit a combat report, saying it was "attacked by the enemy, requested support in the form of a 155mm-howitzer shell, and defeated the enemy with it." The 155-millimeter artillery of the battalion headquarters would also be pleased to have received such a request from the first lieutenant general, as it had been a while since they last had the opportunity to feel that their contribution is of value.

The carbine was originally a "back-up." If the South Korean military wanted to report its previous record of "destroying the enemy" to its superiors, it had to submit weapons acquired from the enemy alongside as evidence. The rifles used most commonly by the North Vietnamese army and the Viet Cong were AK47s and carbines. Each platoon somehow managed to procure a carbine(s) from somewhere. It was likely that they made a deal with the South Vietnamese army. Such carbines were usually carried as "surplus weapons" during operations. They submitted these when they were reporting their incidents of slaughtering the enemy, as proof, especially if they weren’t able to acquire too many of the enemy’s weapons. The carbine was also perfect for when they staged enemy attacks. It wasn’t like the jungles were filled with flying bullets at all times. There were in fact times when no matter how thoroughly they searched, they couldn’t so much even find a single rat. If there was no enemy, they fabricated enemies.

The same was true two months ago on February 12. The first company, to which Lieutenant Choi Young-un belonged, entered the fire-controlled area of the Phong Nhị and Phong Nhất villages and fired at the residents without cause. Rumors were rampant that it was the working of some platoon or squadron that was coming from behind. The U.S. military sent a letter to the South Korean military demanding an explanation about the incident. Here again, 'Kara' was conveniently deployed. According to the report compiled by the South Korean Marine Corps' military police after investigating the captain, some platoon leaders and senior officers, no one in the first company entered the Phong Nhị and Phong Nhất villages that day or partook in the shooting. Instead, they fabricated the fictitious existence of some Viet Cong, camouflaged in ROK military uniforms. A month after the aforementioned "Kara carbine operation,” Lieutenant General Choi Young-un was transferred from being the 1st platoon leader to deputy captain. His position entailed residing in the company base in Hoi An and overlooking the day-to-day of the company members. This marked a new beginning for him.

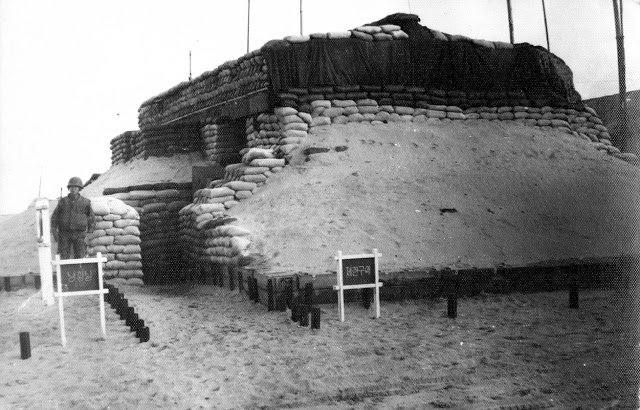

The headquarters of the first company, located 4 km west of the battalion headquarters in the Điện Bàn District. A sentry stands guard in front of a bunker with a solid stack of sandbags. Photography by Choi Young Un

The summer of 1968. It had only been several months since he became deputy captain. Choi was on his way out from shopping at the U.S. Post Exchange (PX) in Da Nang in a South Vietnamese army jeep. The South Vietnamese driver grabbed the steering wheel. In the back seat was a pile of salem cigarettes and Coca-Cola, along with a Sony black-and-white television. In order to get to Hoi An where their base was, he had to take Route 1 from downtown Da Nang. A worn-down jeep in the back suddenly turned on its emergency lights and followed along at a rapid speed. There was a small antenna on top of the car. An American soldier in street clothes stuck his head out of the window. When they stopped at the light, the American flashed his U.S. military intelligence unit ID card and demanded that he follow. He had undoubtedly found it strange that a South Korean Marine officer leaving the U.S. Army's PX in a South Vietnamese jeep. He seemed to suspect illegal commodity circulation and transactions. It was common for various supplies and PX products from the U.S. military to flow into the black market via the South Vietnamese military and then into the hands of the Viet Cong.

The suspicion was unfounded. Lieutenant Choi felt wrongly accused. Without doubt, such transactions happened quite frequently, but their scale was always negligible. In fact, it went like this:

Lieutenant Choi, the deputy commander, would offer to fill the gasoline tank of the jeep of the South Vietnamese army artillery officer next to their base in Hoi An. There were no jeeps in the South Korean military base, but they could get as much gasoline from the U.S. military through the battalion supply chain. The South Vietnamese artillery officer would then go to the market and somehow cash a portion of the free gasoline. The deal was that Choi, in return for supplying free gasoline, would be allowed to use the jeep when he needed it.

One day, Lieutenant Choi, along with a South Vietnamese driver, headed for the U.S. Army PX in Da Nang in the jeep. It was an hour drive. He wanted to buy a 24-inch black-and-white television set for a soldier who was scheduled to return home. While he was at it, he decided to buy some items that he needed. It was a time when TV was still a rare commodity in Korea. South Korean soldiers could not purchase a TV no matter how much money they had. The military also banned the purchase of expensive electronic goods in order to encourage soldiers to remit money back home. Lieutenant Choi received $107 in U.S. military currency certificates for the TV from a soldier who was scheduled to return home. A sergeant’s monthly combat pay was $54. He most likely remitted most of his pay but saved up little by little all year long. Choi had already purchased a black-and-white TV from the U.S. military PX with his officer ID card, using up his allotment. A small puncture in one's ID card indicated the fact. He therefore needed to find another way.

Lieutenant Choi arrived at the U.S. Army PX in Da Nang. The PX, with its open structure, was as wide as a department store. Choi, who toured the entire PX, went outside to where there was a grass field. U.S. soldiers on vacation were thrashing about. He grabbed one of them and offered to buy him a bottle of Cutty Sark. Young U.S. soldiers loved whiskey, but they weren’t allowed to purchase any, even if they had a lot of military currency certificates. Only for the South Korean military officers was it possible. The face of the U.S. soldier lit up at the offer. Lieutenant Choi stipulated the conditions: "Purchase a television for me in return."

This was not at all difficult for the U.S. soldier. The deal was sealed. They bought a Sony TV and Cutty Sark whiskey respectively and exchanged them along with military currency certificates. Choi picked up a few cartons of Salem cigarettes, one of the 3S's that the Vietnamese people died for. The 3S, along with Salem, referred to Sony and Seiko. These Japanese products were the most cashable products on the black market.

Unfortunately, Choi was caught by a U.S. military intelligence agent after coming out of the PX. The U.S. soldiers contacted the South Korean Marine Corps. The agents of the 2nd Brigade of the Korean Marine Corps came immediately to take custody over Choi. He explained the whole story at the brigade's military police. "I understand your situation, but we can’t just let you go," the investigator said. It was because they were wary of the U.S. military. In the end, everything, including the TV, was confiscated.

The tables turned however, thanks to 'Kara'. Lieutenant Choi Young-un practiced forging the signature of Colonel Yeom Tae-bok, the brigade's chief of staff, which he found among the battalion's personnel affairs files. He thereafter forged an official document. The sender was Chief of Staff, Yeom Tae-bok, and the recipient was the chief of the military police. He forged a good signature of the Chief of Staff at the bottom of the document asking for the "immediate return of the confiscated goods from First Lieutenant Choi Young-un." His inspiration came from Rene Clement’s movie, “Plein Soleil”, wherein the main character, Alain Delon, forges a friend's signature in a letter. The counterfeit document forged by Choi took immediate effect. The police returned all the confiscated goods. Choi assured himself that at least it wasn’t out of self-interested motives. It was altruistic of him to give the returning soldier a TV as a farewell gift.

They went through surprise audits by the brigade's headquarters because of the C rations. It all happened when he ran into an old classmate from Busan High School who now happened to be a transport officer, while he was guarding a vehicle carrying military supplies from the 100th Logistical Command on Route 1. His friend gave him dozens of boxes of C ration from the storage area of the brigade headquarters, which he carried back on the truck. Despite the large pile they kept in the storage area, the soldiers were fed up with the instant food they ate every day. After agonizing over how to deal with the ration boxes, he began selling them to the South Vietnamese Army via a major supply sergeant. With the money they earned, they bought Budweiser beer and celebrated among themselves.

The inspection at the brigade headquarters was because the U.S. military raised an issue over this. They had aerial photos showing Vietnamese civilians walking into a village in the mountains in long lines, carrying something on their heads like ants. On closer inspection, they were able to decipher that they were transporting C ration boxes. A single box contained 12 portions. There was no telling whether the boxes were from the first brigade. They could have gone through the black market and into the mountains to supply Viet Cong with food, but the odds were still high that they were from the brigade.

Auditors cross-referenced the supply documents with items in the warehouse. They found nothing amiss. The documents were impeccably arranged.

The Vietnam War was a war of guns and bombs, and at the same time, a war of underhanded dealings. Behind the scenes, there were all sorts of "Kara" activities, both big and small. In fact, it was the U.S. military that took center stage in all of this. Lieutenant Choi Young-un, who was transferred from being the deputy captain of the first company to the personnel administration office of the battalion in the fall of 1968, witnessed all of it firsthand. It was a day of heavy rain.

- Written by humank (Journalist; Seoul, Korea)

- Translated and revised as necessary by April Kim (Tokyo, Japan)

The numbers in parentheses indicate the respective ages of the people at the time in 1968.

This series will be uploaded on Steemit biweekly.