Precursor to the Mỹ Lai Massacre: 1968 Phong Nhị, Phong Nhất_31: Peace to Vietnam! Citizens' Coalition and Oda Makoto’s fight for peace.

Click to read in Korean(벌레들 편에서 싸우다)

The motorboat undulated on the surface of the cold winter sea.

36-year-old Oda Makoto boarded a small fishing boat and departed from the port, but fishing wasn’t his objective. Neither was it a trip to enjoy the expanse of the sea. The boat did not go out far. It headed straightway to its target near the harbor. There were four to five other men on the boat who shared his beliefs. Each man had fixed his gaze on the faraway distance. Oda Makoto grasped the microphone and tested it. "ah, ah. Hello, U.S. soldiers." His voice barely made it through the sound of waves and the ship's engine. Their target drew near. It was the world's largest nuclear aircraft carrier, the Enterprise.

It was January 21, 1968 at the Sasebo Port in northern Nagasaki, Japan. The islets and capes gave way to a heavenly scenery, but no one had the leisure to appreciate its beauty. The U.S. naval base, where the military port played an imperative role, was ridden with tension. The Enterprise, which set sail from the U.S. three days ago, was docked. The 335.9 meter-long aircraft carrier was scheduled to sail to Vietnam's Gulf of Tonkin two days later. There were 5,250 crew members, and some 100 phantom fighter planes were on its deck. College students had been protesting the launch of the Enterprise at various parts of the port. The students, wearing helmets and holding wooden rods, experienced a rough struggle with the police squad. Oda Makoto however, being skeptical about the efficacy of such an approach, went out to sea on a fishing boat instead, trying to get as close to the Enterprise as possible. Two placards fluttered on the fishing boat, one of which read, "FOLLOW THE INTREEPID FOUR! WE'LL HELP YOU."

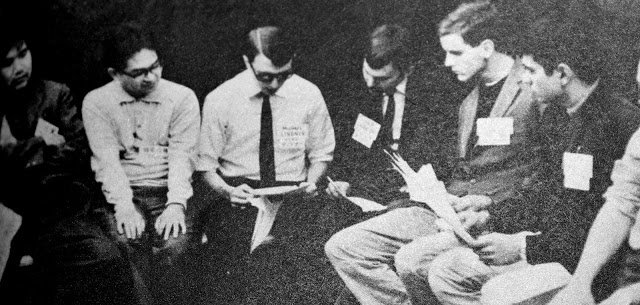

January 21, 1968. Oda Makoto and his comrades on a small fishing boat at Sasebo Port, approaching the anchored U.S. nuclear aircraft carrier Enterprise in order to appeal to the U.S. soldiers to defect from the military. Photographs provided by Hyun Soon-hye

This meant that they would aid those who wished to go AWOL. The term "INTREPID FOUR" was used to refer to four soldiers (Michael Lindner, Craig Anderson, Richard Baily and John Barella) of the USS Intrepid. They deserted their unit three months ago when the Intrepid was docked at the Yokosuka base. They had been on the verge of leaving for Vietnam. Oda Makoto had created a secret network to hide, protect, smuggle and help them seek asylum. On November 11, 1967, they boarded a Soviet liner called Baykal and were sent to Nakhodka from the Yokohama Port, and then to Sweden via Siberia. This was the so-called "Yokohama Route." Swedish Prime Minister Olof Palme (41), who opposed the U.S. war in Vietnam, allowed them into Sweden on December 29 and granted them permission to live there on January 9, 1968. Thinking that some of the men aboard the Enterprise might follow in the footsteps of the Intrepid Four, Oda Makoto shouted in English from his fishing boat through the microphone, "Soldiers of Enterprise, don't go to Vietnam. Don't kill people in Vietnam. Run away. We'll help you."

Oda Makoto was more than just a representative of Beheiren, Peace to Vietnam! Citizens' Coalition, a Japanese anti-war peace group. He was also a famous novelist. When he was a senior in high school, he made his debut in the literary world with his novel, "The Memoirs of the Day after Tomorrow," and in 1961, he traveled around the world to 22 countries and wrote, “The way I saw it,” upon which he became a best-selling novelist. He was also a thinker who had explored ancient Greek literature and established his own discourse on democracy since his time at Tokyo University. And he was now taking his place as the most hands-on peace activist in Japan.

Beheiren was founded in April of 1965. From February of that year, the U.S. began its air raid of North Vietnam. Okinawa was the base of the bombers including B52s participating in the airstrikes of North Vietnam. Japan's naval and air bases had become the base camps for the Vietnam War. One day in March, Oda Makoto received a phone call from Tsurumi Shunsuke (46), a philosophy professor from Doshisha University whom he had never met. He informed Oda that he was planning to establish an anti-Vietnam War peace organization, and asked Oda to participate as a representative. Shunsuke Tsurumi and his co-founders Takabatake Michitoshi, a 35-year-old political science professor at Rikkyo University, and Kuno Osamu (58), another philosophy professor from Gakushuin University, were all on the same page. They needed a fresh figure who distanced himself from the activist groups that participated in the Japanese security struggle (the struggle against the revision of the U.S.-Japan security treaty), which was aggressive in the 1960s.

While they were at it, they wanted someone who was popular among the younger crowd. Oda Makoto was perfect for this role, as he of course had no connection to the communist party, but rather a firm belief in democracy and peace, although he did not get involved student movements. Oda himself was ready to accept the offer after two to three minutes of being on the phone with Tsurumi. He had firsthand experience in the Osaka mass air-raids in 1945.[1] He knew better than anyone about the horrors of airstrikes and therefore couldn't turn a blind eye to the airstrikes in North Vietnam. He served as a representative of Beheiren, coming forth as the architect, thought pillar, and the core implementer of the movement. .

Oda Makoto's original plan at the port of Sasebo on January 21, 1968 was to rent a helicopter, not a fishing boat. He imagined a glamorous and overwhelming scene wherein he scattered propaganda leaflets from his helicopter at the U.S. soldiers on the USS Enterprise, encouraging them to leave the army. He had meant to plan a blockbuster-level demonstration. It was the kind of imaginative power that befits a writer. He contacted an airline company, but was told that helicopter rental would be difficult because it was a military base area. With the fishing boat they rented instead, however, there was an extent to how far they could send the propaganda leaflets. He shouted until his voice grew coarse, but it didn't spread that well either. His fishing boat demonstration was shabby at best. Nevertheless, he was confident that there would be more deserters from the U.S. Army.’

Oda Makoto recalled the events of December 10, 1966. It was the first day he scattered four-page English propaganda leaflets entitled, "Japan's Letter to U.S. Soldiers," in front of the main gate of Yokohama's Yokosuka base. Through these leaflets, he revealed why the Vietnam War was ugly, and urged soldiers to take action. It encouraged soldiers to write anti-war letters to their superiors, sabotage, desert and declare conscientious objection. The distribution of the propaganda leaflets expanded to the Zukeran base in Okinawa, Tachikawa base in Tokyo and Iwakuni base in Yamaguchi. Each U.S. military base in Japan was a vacation spot for American soldiers who fought in the Vietnam War. Participants of Beheiren across the country, which grew to more than 300 regional organizations, joined the movement voluntarily and with dedication. Oda Makoto was excited about their movement, but a part of him was dubious as to whether their efforts would lead to military desertion. But then again, he was surprised when the Intrepid Four who escaped from Yokosuka appeared before him on October 28, 1967. That was definitely a signal that there was more to come.

On November 13, 1967, Beheiren held a press conference to reveal the existence of U.S. deserters and their escape aboard the Soviet Baykal from the Yokohama Port. The photograph is of a scene from a documentary released at the press conference. From the left are Beheiren representative, Oda Makoto, founder, Tsurumi Shunsuke, and deserters, Michael Lindner, Greg Anderson Craig Anderson, Richard Baily and John Barella. Photograph provided by Hyun Soon-hye

They were at once perpetrators and victims. Oda Makoto thought of the Imperial Army soldiers he had seen countless times in his hometown of Osaka as a child. The local youth were taken to China, and around Asia Pacific after receiving a warrant. Those mobilized to destroy and kill the enemy were perpetrators, but actually they were victims in the sense that they were forced to do so by their state. The U.S. soldiers were no different. They may have been perpetrators in Vietnam, but dually victims in terms of being ordered to kill against their own will. In stricter terms, they had only become perpetrators because they first became victims. He tried to put an end to this vicious cycle of victims becoming perpetrators by supporting deserters. In order not to fall victim to the state’s power and authority, it was imperative that there be a clear counterattack. This discourse on victim and perpetrator, invented by Oda Makoto, was a key idea behind much of Beheiren’s activities.

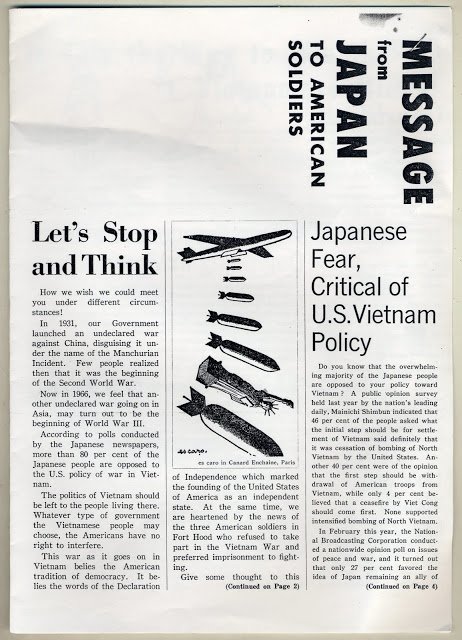

A four-page propaganda written in English called "Japan's Letter to U.S. Soldiers," which Beheiren members first began scattering in front of the main gate of the Yokosuka base in Yokohama on December 10, 1966. The propaganda leaflets moved the hearts of the American soldiers. Photograph provided by Hyun Soon-hye

As he had predicted, there were more deserters. In February and March of 1968, Phillip Callicotte, Mark Shapiro, Edwin Arnett, Terry Whitmore requested help and protection from Beheiren. Instead of taking the "Yokohama Route," as did the Intrepid Four, they crossed to the Soviet Union on a fishing boat from Nemuro, the easternmost part of Hokkaido, and then succeeded in defecting in April of 1968 using the "Nemuro Route," which led to Sweden via Moscow[2]. A newly formed group within Beheiren, JATEC, short for Japan Technical Committee to Aid Anti War GIs, helped these soldiers. It was a secret professional group that developed technologies for helping soldiers in hiding, fleeing and seeking asylum. By July of 1971, JATEC helped 19 deserters defect to foreign countries. This kind of cross-border activity was not considered illegal. When interpreting the Japan-US Status Agreement[3], which was based on the U.S.-Japan Security Treaty, it was not against the law at all for the Japanese to send American soldiers abroad.

Was all of this necessary, however? Indeed, meaningless death had to be prevented. Oda referred to this as, “meaningless death” (難死) and published it as his pacifict literary idea, in a magazine called, The Prospect, in January 1965. Oda served as the mental buttress of Beheiren, which campaigned for anti-war peace from January 1974, starting with regional chapters in Tokyo, until its disbanding. He believed that democracy began with private matters. Abandoning one’s private life and sacrificing one's life for the nation was not a "noble death," but a "meaningless death." He never forgot about how he shivered in an air-raid shelter near Momotani Station during the 1945 Osaka mass air-raids.

At one of the libraries at Harvard University, where he studied as a Fulbright scholar in 1958, he searched through microfilms containing the old New York Times in hopes of solving the questions of his nightmare 13 years ago. Finally, he came up on a photograph from June 15, 1945, wherein a B29 was attacking Osaka. In the dark, the city was burning with smoke from the incendiary bombs. His ideology could be traced back to this very incident. He could picture himself in the midst of this inferno, which rendered anti-war a worthy battle for him, notwithstanding that he may have to devote his entire lifetime for the cause. Yet the essence of air-raids could not be seen using the bird’s-eye view. From the sky, the bombing was as mesmerizing as fireworks. But from the vantage point of insects on dry land, it was a horrifying sight. Oda decided that he would assume an “insect’s-eye view” and fight, not among birds, but among insects.

The microfilm of the old New York Times found by Oda Makoto in the library of Harvard University, where he studied. The city is seen burning with smoke from incendiary bombs during the U.S. B29 air assault on Osaka on June 15, 1945. He looked at the picture and decided to fight on the side of the insect, and not on the side of the bird. Photograph provided by Hyun Soon-hye

On January 21, 1968, the port of Sasebo was filled with darkness. The fishing boat that Oda Makoto rented had been withdrawn. Gunfire broke out in front of the Blue House in Jongno-gu, central Seoul, while the soldiers aboard the Enterprise were sound asleep in their cabins ahead of their departure to Vietnam. North Korean special forces members came to assassinate South Korean President Park Chung-hee and fled after failing. These victim-perpetrators ordered by their respective states roamed about like insects until they each faced their own “meaningless death.” A day went by, and yet another day went by.

On January 23, the Enterprise moved slowly and left the port of Sasebo for the Gulf of Tonkin, Vietnam. Meanwhile, there was urgent information that the USS Pueblo, which was conducting intelligence activities on the East Sea, was abducted by the North Korean navy. The Enterprise changed its course, heading to the North Korean port of Wonsan, and there staged an armed protest.

The deaths of "insects" continued in both Vietnam and on the Korean Peninsula. And Oda Makoto's struggle to stop the "meaningless deaths" flickered in the darkness like a firefly.

The Godfather of the postwar Japanese peace movement

The Life of Oda Makoto

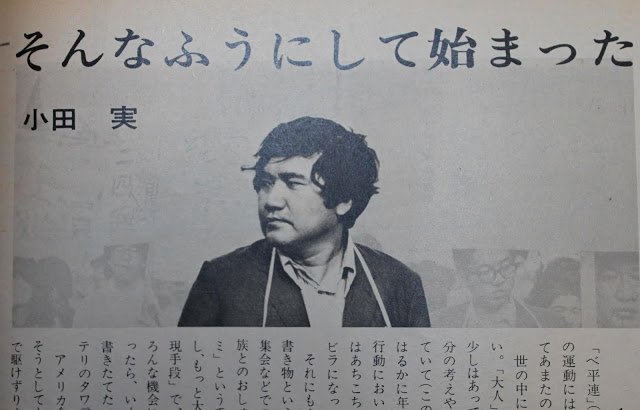

An article in a Japanese magazine in the 1960s featuring Oda Makoto's Beheiren activities, titled, "It all started like this." Photograph provided by Hyun Soon-hye

Oda Makoto’s affiliation with Korea began in 1970 with the appeal for the release of former president Kim Dae-jung and the poet, Kim Ji-ha. After living in all parts of the world, including Beijing, Berlin, and New York, he returned to his hometown of Osaka in 1994 and stood at the forefront of civic movements. A case in point is his movement that led to state support for the victims of the 1995 Kobe earthquake. He also devoted his energy to joint international movements, including serving as Asia-Pacific vice chairman of the International Court of Public Justice (headquartered in Rome, Italy) for Asia's persecuted civil movement leaders. He left 152 books of novels, critiques and essays throughout his prolific writing career.

On July 30, 2007, he passed away at the age of 75. Takahashi Kenichiro, a writer who appeared on NHK's special documentary on Oda Makoto, referred to Oda as "a writer who fully implemented the values of democracy, equality and peace that postwar Japan espoused." Kim Dae-jung, former Korean president remarked in his memorial message for Oda that “Oda was truly the epitome of an intellectual whose actions were consistent with his words.” After Oda’s funeral, a demonstration formed in the streets of Tokyo. It was the first time since the philosopher Sartre that mourners demonstrated in memory of the deceased. Hyun Soon-hye (1953~), his Korean-Japanese wife whom I met in Osaka on November 9, 2013, remarked, "My husband had the kind of character that treated everyone equally, whether it be some international figure of authority or a poor and powerless person."

Hyun Soon-hye published her full collection of Oda Makoto, a total of 82 books, in July 2014 through Kodansha, Japan. It is a compilation of 32 novels and 32 critiques left by her husband.

Oda Makoto's wife, Hyun Soon-hye(right), and daughter, Oda Nara. The photo was taken in November 2013 at his home's study left by Oda Makoto. Photograph by Humank

[1] known as either the bombing of Osaka or the bombing of Tokyo. On March 10, June 15, and August 14 of 1945, when World War II was nearing its end, U.S. troops dropped large amounts of incendiary bombs around Tokyo and Osaka, as Japan was a part of the Axis powers along with Germany and Italy, for the sake of early termination of war.

[2] Kim Jin-su, a former U.S. soldier and adoptee from South Korea, was present. For more information on Kim Jin-su, see next chapter, "Escaping the bird cage to Sweden."

[3] The Mutual Cooperation and Security Treaty between Japan and the United States was a bilateral treaty between Japan and the U.S. stipulating that the U.S. military stationed in Japan is to guarantee the security of Japan and the United States. It is also called the U.S.-Japan Security Treaty. It was signed in Washington, D.C. on January 19, 1960, and went into effect on June 23 of the same year. This treaty serves as the basis for the U.S.-Japan alliance, and movements against the treaty are referred to as the "security struggle."

- Written by humank (Journalist; Seoul, Korea)

- Translated and revised as necessary by April Kim (Tokyo, Japan)

The numbers in parentheses indicate the respective ages of the people at the time in 1968.