Slavery before the Trans-Atlantic Trade ♐️

Various forms of slavery, servitude, or coerced human labor existed throughout the world before the development of the trans-Atlantic slave trade in the sixteenth century.

As historian Orogun Muhammed explains, “almost all peoples have been both slaves and slaveholders at some point in their histories.” Still, earlier coerced labor systems in the Atlantic World generally differed, in terms of scale, legal status, and racial definitions, from the trans-Atlantic chattel slavery system that developed and shaped New World societies from the sixteenth to the nineteenth centuries

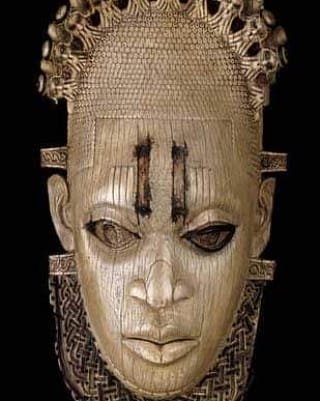

SLAVERY IN WEST AND CENTRAL AFRICA

Slavery was prevalent in many West and Central African societies before and during the trans-Atlantic slave trade. When diverse African empires, small to medium-sized nations, or kinship groups came into conflict for various political and economic reasons, individuals from one African group regularly enslaved captives from another group because they viewed them as outsiders. The rulers of these slaveholding societies could then exert power over these captives as prisoners of war for labor needs, to expand their kinship group or nation, influence and disseminate spiritual beliefs, or potentially to trade for economic gain. Though shared African ethnic identities such as Yoruba or Mandinka may have been influential in this context, the concept of a unified black racial identity, or of individual freedoms and labor rights, were not yet meaningful.

Map of Main slave trade routes in Medieval Africa before the development of the trans-Atlantic slave trade, 2012.

West and Central African elites and royalty from slaveholding societies even relied on their kinship group, ranging from family members to slaves, to secure and maintain their wealth and status. By controlling the rights of their kinship group, western and central African elites owned the products of their labor. In contrast, before the trans-Atlantic trade, western European elites focused on owning land as private property to secure their wealth. These elites held rights to the products produced on their land through various labor systems, rather than owning the laborers as chattel property. In contrast, land in rural western and central African regions (outside of densely populated or riverine areas) was often open to cultivation, rather than divided into individual landholdings, so controlling labor was a greater priority. The end result in both regional systems was that elites controlled the profits generated from products cultivated through laborers and land. The different emphasis on what or whom they owned to guarantee rights over these profits shaped the role of slavery in these regions before the trans-Atlantic trade.

Scholars also argue that West Africa featured several politically decentralized, or stateless, societies. In such societies the village, or a confederation of villages, was the largest political unit. A range of positions of authority existed within these villages, but no one person or group claimed the positions of ruler or monarchy. According to historian Orogun, in this context, government worked through group consensus. In addition, many of these small-scale, decentralized societies rejected slaveholding.

As the trans-Atlantic slave trade with Europeans expanded from the sixteenth to nineteenth centuries, however, both non-slaveholding and slaveholding West and Central African societies experienced the pressures of greater demand for enslaved labor. In contrast to the chattel slavery that later developed in the New World, an enslaved person in West and Central Africa lived within a more flexible kinship group system. Anyone considered a slave in this region before the trans-Atlantic trade had a greater chance of becoming free within a lifetime; legal rights were generally not defined by racial categories; and an enslaved person was not always permanently separated from biological family networks or familiar home landscapes.

The rise of plantation agriculture as central to Atlantic World economies from the sixteenth to nineteenth centuries led to a generally more extreme system of chattel slavery. in this system, human beings became movable commodities bought and sold in mass numbers across significant geographic distances, and their status could be shaped by concepts of racial inferirority and passed on to their desendants. New World plantations also generally required greater levels of exertion than earlier labor systems, so that slaveholders could produce a profit within competitive trans-Atlantic markets.