BIOGRAPHY

Solon was born in around 638 BC in Athens. His father was either Euphorion or, more likely, Execestides, a man of some wealth and political influence, and from a distinguished Athenian family. Solon’s mother was Heraclides of Pontus, a cousin of Pisistratus’s mother, and this relation between Solon and Pisistratus made them quite close. There are also accounts that Pisistratus was good-looking, attracting Solon to him, a possible explanation as to why their eventual rivalry was one free of physical brutality.

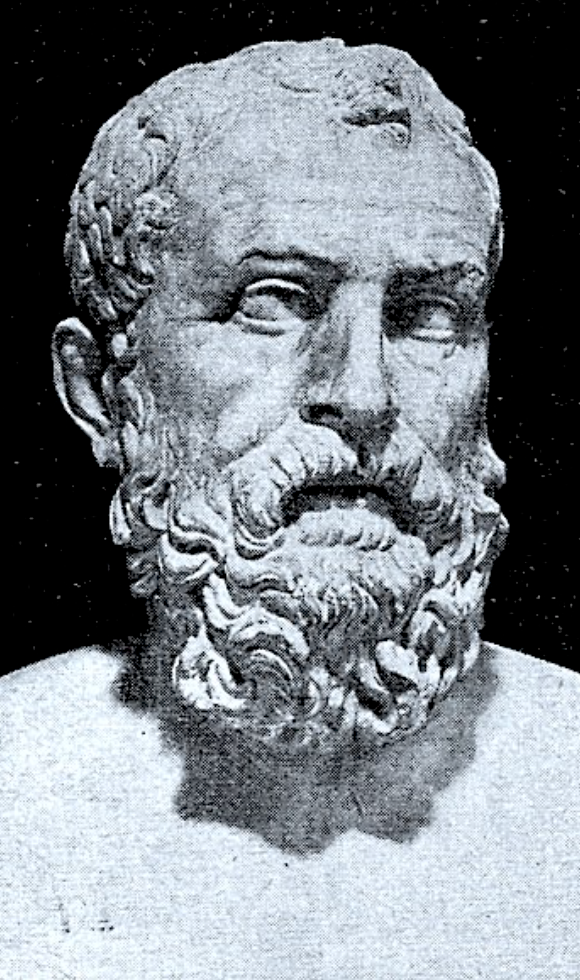

(Copy of an original Greek bust of Solon, 110 BC, now at the National Archaeological Museum, Naples)

EARLY LIFE

Solon started out his life as a trader. Some say his travels were for broadening his mind and for experience instead of business-related reasons; it’s true that, even when old, he “never stopped learning as he grew old”, and he was never impressed by wealth, going so far as to state that two people are as well-off as each other when one:

“has much silver

And gold, and wide wheat-bearing fields,

And horses and mules, while the other has only enough

To keep belly, body and feet in comfort,

And to enjoy the youthful bloom of woman and boy

When they too arrive, and become agreeable in their season.”

But otherwise, he states:

“Money I would like to have but not unjustly gained;

For in the end justice always comes.”

EARLY WRITINGS

His extravagance and luxury and his poems addressing pleasure like a normal man instead of like a philosopher is attributed to his earlier days spent as a trader; In return for all considerable risks he undertook, he wanted back some luxurious reward, but he still classed himself as a poor man:

“While good men are often poor, many and men are rich;

Still, I would not exchange with them

My goodness for their wealth; for goodness endures,

While different men have money at different times.”

Solon took up poetry lightly when he first started, more as a personal hobby. He would go on to put philosophical maxims to verse too, intertwining it with politics too, more to justify his actions and advise or scold the people of Athens, rather than retelling events to preserve history. He also used epic verse to promote his laws:

“Let us begin with a prayer to Lord Zeus, the son fo Cronus,

That they may grant these laws good fortune and acclaim.”

When it came to ethics, Solon was magnetised to philosophical politics, a social norm for ponderous men of that time. His ideas when it came to physical sciences were more simple, and fairly old-fashioned:

“Clouds give rise to the form of snow and hail,

And thunder comes from bright lightning.

The sea is churned up by the winds, but if no wind

Disturbs it, there is nothing more equable.”

THE 7 SAGES

Of Solon’s early group, Thales was one who’s mind would dwell in bounds beyond that of functional needs, while the rest of the 7 Sages gained their wise reputations by using their skills within the world of politics. The 7 Sages were 7 philosophically inclined men which included:

• Solon

• Thales of Miletus

• Bias of Priene

• Pittacus of Mytilene, Lesbos

• Chilon of Sparta

and two of either:

• Cleobulus of Lindos, Periander of Corinth, Myson of Chenae or Anacharsis of Scythia (the sources vary)

THE STORY OF HELEN OF TROY'S TRIPOD

The Seven Sages once gathered together, organised by Periander, at Delphi and then at Corinth. He organised for them a meeting-cum-symposium, however their reputations and renowns was set as they each said their piece on the story of the tripod; as the story goes, Coan fishermen hauled a net in, when some visitors from Miletus bought the catch off of them unseen. When the net reached land however, it contained a gold tripod, supposedly dropped by Helen on her visit to Greece from Troy. Disputes on who should keep the tripod arose between the Coans and the visitors, until eventually a war broke out. It was then that the Pythia from Delphi gave both sides a message, stating that the tripod should belong “to the wisest”. First, it was sent to Thales in Miletus, as the Coans wouldn’t dispute over showing just one man. However, Thales stated that Bias was wiser than all, passing the tripod to him instead, but Bias gave it to someone else believing them to be wiser still. It carried on like this until it ended up back with Thales. It was then just given to Thebes, where it was dedicated to Ismenian Apollo.

Theophrastus claimed Bias to be the first man to receive the tripod in Priene, and it was he who sent it to Thales in Miletus. In this version, once the tripod went around to everyone who was believed to be wiser than the previous recipient, it returned to Bias, and then was sent to Delphi. Other versions of the story claim that the tripod was actually a cup left by Bathycles, or a bowl sent by Croesus.

ANACHARSIS VISITS SOLON

While on his way to Athens, Anacharsis visited Solon’s home, stating:

“I’m not from here, but I’ve come to forge ties of friendship and hospitality with you.”

When Solon claimed that this was something best done at home than elsewhere, Anacharsis said,

“Well you’re the one at home, so why don’t you forge ties of friendship and hospitality with me?”

Solon, taken in by his wit, made him welcome, allowing him to stay for a while.

This was all during a time when Solon was involved in politics and was writing up his laws. Finding out Solon’s beliefs, Anacharsis mocked, stating he could simply utilise decrees to stop the injustice:

“These decrees of yours are no different from spider’s webs: they’ll restrain anyone weak and insignificant who gets caught in them, but they’ll be torn to shreds by people with power and wealth.”

Solon responded by stating that people stick to agreements when both sides don’t gain from it by infringing them, and that he was making his laws best suit the people to prove that honesty is always better than criminality. The results would, however, prove Anacharsis, and not Solon, right, and Anacharsis also showed surprise, after a visit to the Assembly, that in Greece proposals were made by the clever, whereas the decisions were made by everyone else.

SOLON VISITS THALES

This is the story according to Hermippus, told by Pataecus:

Solon, visiting Thales in Miletus, expressed surprise to Thales disregarding marriage and having children. When another visitor from Athens showed up, Solon asked what the latest from the city was, and the man, on orders, said:

“Nothing… Oh, except for the funeral procession of a certain young man, which was attended by the whole population. I was told that his father was someone distinguished, whose excellence made him the foremost man in Athens. The father wasn’t there, however; they said he was abroad and had been for a long time.”

Solon asked what the deceased’s name was, but the man had forgotten:

“All I can remember is that people went on about his wisdom and justice.”

This all made Solon more worried, until he told the visitor his name, and found out that the dead man was indeed his own son. Beating his own head, Thales took his hand and smiled:

“This is what makes me steer clear of marriage and parenthood, Solon. It overwhelms even you, and there is no one stronger than you. But don’t be alarmed at this tale, because it isn’t true.

THE SIEGE OF SALAMIS

Athens had engaged in a long war with Megara, based on the isle of Salamis. Eventually, the tired Athenian people passed a law, in which Athens should never again attempt to claim the island for themselves, on pain of death. Solon took this humiliation hard, while noticing that the younger members of Athens wished to see war resume, although they didn’t want to make the move themselves in fear of the law. He thus pretended to go insane, and his family spread word of this around Athens. Meanwhile, he stayed in his home making elegiac couplets, rehearsed them and made a sudden visit to the city centre, wearing a felt cap. In front of a crowd, Solon stood atop the herald’s block and recited his couplet:

“I have come as a herald from fair Salamis

With no speech but a composition in ordered verse.”

The poem, named “Salamis”, contains 100 lines. His friends applauded him when he finished reading it, and Pisistratus urged the people to follow Solon’s words. Eventually, Athens repealed the law, and war resumed with Megara, with Solon as commander.

Solon and Pisistratus accompanied the fleet to Cape Colias, where women were sacrificing to Demeter. He thus sent a fake deserter, a man he trusted, to Salamis. The man told Megara that they could capture every leading woman in Athens so long as they sailed with him back to Cape Colias. Falling for this ploy and sending a squad of armed troops, Solon ordered the women to flee and dressed up young men in dresses instead, sending them to the shores armed with concealed swords to take the Magarian troops by surprise and seize their ships from them. None of them escaped, and when this was done, the Athenian fleet took over Salamis with ease.

SOLON'S GROWING INFLUENCE + HIS FIRST LAWS

Solon by now had made a name for himself. His speeches had roused the Greeks to defend Delphi from the Cirrhaeans, he persuaded members of the Cylonian affair to submit to a trial and to be judged, and his influence persuaded others to help him write up the rest of his laws.

Perhaps Solon’s biggest law change was the institution of propitiatory and purification rituals, as well as the founding of worship places, allowing him to make Athens a revered religious city that highly observed good justice and lean towards populace unity.

("Solon, the Wise Lawgiver of Athens" by Walter Crane)

THE PLAINS, HILLS + COASTAL FACTIONS

In Solon’s time, three factions, divided by wealth and terrain, existed among the Athenian population: The Hills Faction were arguably the most democratic, the Plains Faction heavily practiced a rule of oligarchy, and the Coast Faction acted almost as an in-between faction, favouring both ways. The Coast Faction also opposed the other two factions, thus made it harder for either of them to gain sole power.

This was all during a time when the division between the rich and poor was at a record high. Things looked so bad that it seemed the only way to solve the issue was the implementation of a tyrant. Commoners were in debt to the upper class, likely because either they had to give them 1/6th of all the produce they made from toiling the lands, or because they often put themselves up as collateral for the debts owed, which could easily have led to them becoming slaves, either in Attica or abroad. Some Plains members even demanded exile, or even the children as slaves. The Hills would gradually get together and rally behind a chosen champion to aid them in removing the debtors, redistributing the land and form a new government altogether.

LOOKING TO SOLON AS TYRANT

From here though, the more straight-minded folk turned to Solon, seeing as though he was least likely from being swamped in all these issues they had. They pleaded for him to engage more in their public life and resolve their issues. It is said however that Solon had a foot in aiding both sides of this conflict: while he did promise to redistribute land, as Phanias of Lesbos claims, he did confirm with the Plains faction that he would reaffirms their existing contracts - Solon was worried about one sides greed and the other’s presumption.

Either way, he was elected to the position of archon, following Philombrotus’ term. He now held the authority to make laws and resolve nation disputes. The Plains favoured him in this position for his wealth, and the Hills favoured him for his integrity. His claims that equality never caused a war pleased both sides too.

Both sides recommended to Solon to become a tyrant, and seize absolute power in Athens. Even members of other factions besides the rich Plains and the poor Hills weren’t against the idea of Solon as a tyrant, as they saw the resolving of these issues via legal measures to be one that would be a laborious and lengthy task. All also favoured him for his honesty and wisdom. It’s also said that Solon received this oracle from the Pythia:

“Take your place amidships, accept the pilot’s job,

And steer the ship; you will find many allies in Athens.”

Solon’s close friends strongly disagreed with him however when he turned away from holding absolute power. He feared it would give him a bad name, as tyrants tended not to have one themselves, and none of what his friends said deterred him from his set ideals. He knew that holding such a post would be a delight in itself, but he knew that there was no way back from it. In his poems, he wrote to Phocus, saying:

“And did I spare the land of my birth?

Did I refrain from tyranny and brutality,

Preferring to keep my name unblemished by disgrace?

There is no shame for me in this. In fact, I think

It will set me above all other men.”

He did ultimately refuse the position of tyrant. This choice gave back to him a lot of scorn, which he also wrote about:

“A man of shallow intellect was Solon, of no good sense;

He spurned the bounty offered by the gods. The fool:

His net was fat and full of fish - he did not pull it in!

He lacked the courage and sanity as well.

Else, if he had taken power, accepted boundless wealth,

And ruled as tyrant over Athens for just one day,

He’d gladly then have been flayed into a wineskin

And let his family be wiped off the face of the earth.”

SOLON AS ARCHON

While he did reject the role of tyrant, it doesn’t mean that he handled his archonship gently. He believed that if he were to make a mess of the state, he himself wouldn’t be able to recover it. His goal for the time being was to “harmonise form and justice”, acting wherever he expected to find those willing to receive his proposals and those who would otherwise submit to applied pressure; When he was asked if his laws were the best ones for the Athenians at the time, he responded, “they were the best they would accept”.

Other writers have noted that Athenians liked to cover the shadier parts of their society with language, calling prostitutes “escorts”, taxes “contributions”, garrisons “protectors” and prisons “quarters”. It’s also worth nothing that this habit might have originated from Solon, who called the cancelling of debts an “alleviation”. He made it illegal for lenders to require a borrower themselves as payment, and thus remove the chances of that person becoming a slave later one. Others have claimed that all this relief for the poorer was a means of moderating interest rates, rather than cancelling debts. This pleased them so much that they called it, as well as the upward rescaling of weights, measures and currency, an “alleviation”. According to some, this was all part of the same law; a mina was previously worth 73 drachmae, whereas now it was worth 100, the bonus to that being that it was still worth the same amount on paper, it was actually worth less, benefitting debtors but not dealing a blow to the creditors. It is widely agreed though that the “alleviation” was an abolishment of due debts, as, in his poems, Solon took pride in having ‘removed’ from the mortgaged land

:

“The frequent markers planted here and there;

A land enslaved once now is free.”

As for the people whose persons were now forfeit through debt, he brought them back from abroad

:

“With Attic Greek no longer on their tongues,

Forgotten in their wide and long wonderings;

While the others, held in sorry servitude here,

In their native land,”

that he claims to have freed.

This is all said to have put him in more trouble than anything else. When he resolved to do away with the debts, he started casting around for arguments and a chance to introduce the measure, going to his closest friends: Conon, Cleinias, Hipponicus and their circle. He was going to leave the land as it already was, but cancel the debts. His friends started on pre-empting the legislation, and borrowed vast amounts of wealth from the wealthy, pooling it together and purchasing big plots of land. When the decree then turned into law, they started profiting from their new estates while refusing to pay debts. This all gave Solon a mass of criticism, however he was the first known person to have obeyed his own law and write off all that was owed to him.

SOLON'S GROWING POWER AND POPULARITY

Solon’s cancelling of debts did annoy the rich, and his failure in evenly distributing land annoyed the poor, and he didn’t remove the gap between rich and poor as previously promised. Lycurgus, for comparisons sake, had done all this, (go to my blog post on Lycurgus and Sparta for more on this) but Lycurgus had, by that time, been in power for some time, and had already amassed power, rank and support for him to see his ideals through, and he relied on force instead of persuasive words to achieve his goals to make sure no one was rich or poor. It even cost him an eye. Solon, however, was still just an ordinary citizen of moderate wealth and resources, but as he only acted due to his citizens accepting his proposals and trustworthiness, he worked with what he had, so he was definitely resourceful.

His ultimate failure to please both rich and poor alike did make it into his own poems though:

“Once their minds were filled with vain hopes, but now

In anger all looks askance at me, as if I were their foe.”

He does, however, state that any other person with that much power

:

“Would not have curbed the people or stopped

Until he had extracted the butter from the churned milk.”

It wasn’t long though until the people saw the benefit of his reforms, as they put said their personal complaints and established a public sacrifice ritual, one that they called the “alleviation”. They also gave power to Solon, entrusting him completely, so he could further reform his constitution to implement further laws on offices, assemblies, the courts and councils. Whatever the case, it was now his decision as to what property qualifications would be needed and how many of them there should be, and when appointments and meetings should be held. He could now also keep or stop any element of an existing system as he pleased.

SOLON'S FIRST CHANGE: REPEALING DRACONIAN LAW

His first move was to repeal Draco’s laws. Draco had been a former tyrant of Athens, who ruled so harshly that we get our own term, Draconian Law, straight from him. Solon repealed all of Draco’s laws, with the exceptions of those on homicide, on the basis that they were just too harsh and thus deserved harsh punishment. The death penalty had been fixed to all crimes, which meant that not working and theft were on the same punishment level as homicide and even temple robbery. (Demades even wrote that Draco didn’t write his laws in ink, but in blood.) Draco believed that petty crimes were deserved of death, and serious crimes could not be punished any worse.

SOLON'S SECOND CHANGE: ASSERTING PROPERTY QUALIFICATIONS

Solon assessed the Athenian citizens’ property qualification. His aim was to leave all political offices in those more well-off while diversifying the all the other political apparatus that the poorer citizens had previously been excluded from. Those in higher offices now had an income of at least 500 units of dry and wet goods (these men were known as the ‘Men of 500 Medimni’). The second class was made up of people who earned 300 units and could also afford their own horse, known as the “Payers of the Knight’s Tax”. Third party qualification consisted of those earning 200 units of dry and wet goods, and were known as “Men with a Team of Oxen”, while the rest of the populace were the “Hired Hands”, and weren’t allowed to hold a political office but were still allowed to attend assemblies and act as jurors. Solon granted office holders the right to appeal to a popular court even in cases which were to be tried, so most disputes ended up in the jurisdiction of the lower class, ending the misconception that their role beforehand was not of importance. It’s also theorised that the reason Solon phrased his laws more obscurely was so he could increase the courts power, in the sense that someone wouldn’t just be able to solve their issues via a court reference, but instead would turn to the juries for aid, bringing every dispute before them to, in a way, make them the masters of the law. His poems tell us that he congratulated himself on this:

“For I granted the people an adequate amount of power

And sufficient prestige - not more or less.

But I found a way also to maintain the status

Of the old wielders of power with their fantastic riches.

I stood protecting rich and poor with my stout shield,

And saw that neither side prevailed unjustly.”

He still felt it necessary to make further provisions for the commoners, giving every citizen the right to institute a lawsuit on behalf of another person who had suffered wrongly. For example, if a man had been assaulted, anyone else who had the resources and the will to bring a lawsuit against the offender, and could go on to prosecute them. This was a good move by the legislator: this was to make the Athenians feel as smaller parts of a larger political body, and to share in each others feelings and suffering. Solon was once asked which city was the best to live in, to which he responded:

“The one where there is no difference between the victims of a crime and anyone else in terms of how vigorously they charge and punish the criminal.”

CITIZEN CLASSES - As his works only survive today in fragments, our knowledge of Solon is fairly limited. Some of his works also appear to have been partially written by later authors. Ancient records of this man mainly can come from Herodotus and Plutarch, yet they wrote about Solon during the 4th century BC, long after he died.

- The Pentakosiomedimni - (pl. pentakosiomedimnoi) These were the top class citizens of ancient Athens after Solon’s reforms. Their property or estate could produce over 25,000 litres cubed worth (500 medimnoi) of wet or dry goods a year. They were eligible for all top positions in government which included the 9 archons and treasurers, the Areopagus Council (ex-archons), the Council of 400 and the Ecclesia.

- The Peletai/Hektemoroi/Thetes - These were the poor in slavery to the rich, along with their wives and children. They worked the fields for the richer people too. Unless they handed over their payments, they and their children became liable to seizure.

- The Zeugitai - Members of Athens' third division after Solon’s reforms who also served as hoplites, wealthy enough to maintain their own equipment.

SOLON'S THIRD CHANGE: NEW ATHENIAN COUNCILS

Solon made it a part of the law that the Council of the Areopagus, the council of wealthy aristocrats who get their name from the ‘Ares Hill’ northwest of the Acropolis, should be constituted out of each year’s list of archons. Solon himself at this point was a former archon, so was counted as one of these members. At the same time, Solon began to notice that the commoners as a result were rather full of themselves, and that cancelling their debts only resulted in them becoming more assertive. To combat this, Solon implemented another council, made of 100 men from each of Athens’s 4 tribes. This new council had the job of debating given issues before they reached the people’s ears, as well as to make sure that the Assembly wasn’t presented with motions which hadn’t ever been through this deliberation process before. On top of this, an upper council was implemented, acting as a guardian to the constitution. Solon’s thoughts were that if ever the state was moored with just two councils, then it would be better equipped to ride out and better contain the population’s restlessness.

Writers generally agree that the Areopagus Council was implemented by Solon himself. Draco never mentioned this council by name, but did refer to the ephetae in cases of homicide. However, Solon’s eighth law was phrased as follows:

“Of the disenfranchised all those who were disenfranchised prior to the archonship of Solon are to regain their rights except those who were convicted by the Areopagus, the Ephetae, or the city hall (that is, the king-archons) of homicide, murder or tyrannical ambition and were already in exile when this law was published.”

This proves the existence of the Areopagus prior to Solon, but the wording of this law could just be ambiguous, or even simply incomplete, so it could mean that those deemed guilty on charges which were at current tried by the Areopagus, Ephetae and officers of the city hall were to stay disenfranchised, while all others were to regain their rights. It’s up to the reader to decide on this though.

LAW ON POLITICAL NEUTRALS

Solon’s other law ordained that a person who didn’t take a side in a political dispute was to be disenfranchised; no one should be indifferent to common goods and to seek the safety of their own private affairs while distancing himself from the current suffering affecting his nation.

LAW ON HEIRESSES

Another law declared that should the husband of and heiress (under the law, he had control over her) be impotent, she had the right to sleep with his close relatives. Some claimed that this was a good move, in order to prevent impotent men from marrying heiresses just for their wealth and using the laws protection to abuse nature; when his attention was fixed to the heiress’s promiscuity, he would have to choose between divorcing her or carrying on being married in shame as punishment for his abuse. The purpose of restricting the heiress to her husbands relatives was so that any children born from these new relations belonged to the same bloodline. When it came to other marriages, Solon did away with dowries, stipulating that brides were to bring 3 clothing items and a selection of cheap home items, nothing else. This was all to remove the commercial and mercenary aspects of marriage and to make raising children, two-way gratitude and affection what a husband and wife should work towards.

LAW ON SLANDERING THE LIVING + THE DEAD

Another of Solon’s approved laws was the one which made it illegal to slander the dead; Piety required people to see the deceased as sacred, decency required people to not attack someone in their absence, and political expediency required people to not allow a conflict to continue indefinitely. Solon also decreed it offensive to slander a live person who was either in or near a temple, court or government offices, and even during public competitions and games. The offence was punishable by a 3 drachma fine for the person involved, and a further 2 drachma fine which went straight to the state treasury.

LAW ON WILLS

Solon also became noteworthy for his legislations on wills, where it was previously not possible for someone to make a will; a mans land and wealth had to stay within the confines of his family. Solon’s new law now made it the man’s choice to dispose of his estate at his own will, as long as he didn’t have children, valuing friendship over kinship, and gratitude over duty. Simultaneously, Solon didn’t allow for property, money or goods gifts without some qualifications: the man giving the gift had to not be ill, drugged, formerly imprisoned, and could not be under the persuasive powers of women; persuading someone to go against their best intents isn’t any different from him being forced to do the same.

LAWS ON WOMEN

Solon’s laws also involved conditions regarding order and neatness on women outdoors, as well as on the manner in which mourners expressed grief and on the correct conduct during festivals. When women were outdoors, she was not allowed to wear any more than 3 items of clothing, she wasn’t allowed to carry more than 1 obol’s worth (722 mg’s) of food and drink, and she was not allowed to travel at night unless she was in a cart with a lamp mounted on the front. Mourners were barred from lacerating themselves, and outsiders were banned from lamenting at someone else’s funeral. Sacrificing a cow at the funeral, laying out more than 3 items of clothing for the dead and visiting the tombs of people outside someone’s own family (except during the funeral procession itself) was now illegal. Offenders of any of this were to be punished by a woman’s superintendents, as the offenders would be deemed to be taking part in unmanly feelings.

CRIME + PUNISHMENT OF WOMEN

In Solon’s laws, while a caught adulterer could be put to death, the rape of a free woman was punished only by a 100 drachma fine, and the seduction of free women was punished by a 20 drachma fine. Women excluded from this included those who willingly gave their bodies. It was also now illegal for anyone to sell off their daughters or sisters, unless it was known for sure that one of them had gone off to sleep with another man. It’s a bit illogical to punish the same crime with death OR a fine depending on the circumstance of course; there could have been a money shortage at the time, so the difficulty in raising it would have made the monetary penalties harsh.

LAWS ON MANUFACTURING, AND FATHER-SON OBLIGATIONS

Attica’s safety drew in a large amount of outsiders, until the city of Athens itself became too crowded. At the same time, the land itself became infertile, leading to foreign naval traders coming to the city not importing as much, as the city had less to give back in return. Solon, aware of this, encouraged his citizens to take up manufacturing-related jobs. He made it law that a son who had not been taught at least one manufacturing trade by his father did not have to support him in later years. The Areopagus, meanwhile, punished those who were unemployed.

Stricter laws made by Solon did exist; Sons born through wedlock were exempt from supporting their fathers. Solon’s thinking behind this was that a man who disregarded an honourable marriage is just looking for a woman for pleasures sake and not to provide him with children, so he would then be paid back in full and would then have no comeback against his children, as he would have made their own births shameful.

LAWS ON SUPPLIES

Solon also changed the value of sacrifice offerings: 1 sheep and 1 medimnus of wheat (51.84 litres) was worth 1 drachma. Rewards for victory at the Panhellenic Games were also changed: victory at the Isthmian Games was now 100 drachma, and 500 drachma for victory at the Olympics. While the prices he set were considered higher overall, they were still a lot lower compared to later times, as recorded by Plutarch.

As Athens didn’t have great sources of water nearby compared to other states, much of the population relied on wells. So Solon implemented legislation allowing anyone to use any well, providing the well was within 1 hippikon (or 4 stades, equal to 2,400 feet / 730 metres) away from their land. A greater distance would require someone to find their own source of water by digging their own holes and wells, and anyone who hadn’t found any water after digging 10 of these, they were allowed to borrow from a neighbour by filling a 6 choes jar ( totalling c.19.5 litres) 2 times a day. This was to encourage people to aid the needy, but limited them so they would not become too idle and reliant on others.

LAWS ON PRIVATE LAND + TREES

Solon proscribed a set distance to be followed when planting trees: no one was allowed to plant a tree in a field if it was 5 feet or less from his neighbours plot (or 9 feet for fig and olive trees as their roots were longer. Some of these trees planted were known to emit harmful secretions, so distancing these fumes from others was the idea behind this. Ditches and pits also now had a fixed minimum gap between each other: the gap had to be equal to its depth. Beehives also had to be at least 300 feet from the hive sites set prior by someone else.

LAW ON OLIVE OIL

Olive oil was to be the only natural produce which was permitted to be disposed of abroad; exporting anything else was illegal. Archons were now to curse for attempting to break this law, or pay a 100 drachma fine.

LAW ON DOGS

Should a person be injured by a dog that was prone to biting, the dog was to have a clog 3 cubits (133.2 cm) long tied onto it as a safety measure.

LAWS ON CITIZENSHIP

Under Solon, the only class of people permitted to become citizens were those who had previously been permanently banished from their former home country, or someone who had moved their entire household to Athens to practice a certain profession. This was done by Solon to encourage different categories of workers into the city to guarantee them a prosperous citizenship. He also knew he could rely on anyone who had willingly left, or was forced out of, their own country.

LAW ON FEASTS

Solon also restricted the privilege of being overfed at publicly-funded tables, a tradition known as “Table Sharing”. It was now illegal to just feed someone over and over again as this implied greed.

SUMMARY OF HIS LAWS + HIS WANT TO START TRAVELLING

All of his laws were decreed to be implemented for 100 years. They were inscribed onto revolving wood tablets and enclosed in frames, and fragments of these tablets survive today. The comic poet Cratinus stated somewhere:

“I swear it by Solon and Draco, whose tablets

Nowadays are used to cook barley.”

the Councils had taken up an oath to uphold Solon’s laws, and each man involved in the legislative committee swore different oaths in the city square, declaring that should they not obey a law, he would dedicate a life-size offering of a gold statue to Delphi.

Once all of Solon's laws were implemented, there wasn’t a day that went by in which he didn’t receive an audience expressing their approval or disproval of a law. People were also known to approach Solon asking about the finite details of each law. Wishing to distance himself from a daily task like this, so claimed, as the owner of his own ship, he had business to attend to elsewhere, using this as his excuse to set off on regular travels. The Athenians permitted Solon 10 years to travel outside of Attica, a period of time he expected the people to have then become accustomed to his laws. While he claims it was to travel, broaden his mind and take in some views, it was more likely a means of avoiding the repercussions of implementing his new laws; The people of Athens couldn’t repeal these laws as they had sworn a solemn vow for 10 years to try out these laws.

SOURCES

• Plutarch, Life of Solon

• Herodotus's Histories

• Oswyn Murray, Early Greece

ALL IMAGES USED ARE ROYALTY FREE

Historia Civilis's video on "The Constituion of the Athenians" (I do NOT own this video)

To avoid making this blog TOO long, I've decided to split it in 2 parts: the second part will be up tomorrow.

Any and all feedback is welcome!

#happystream 487

Wow, thats is a lot of information ^^ quite a lot of laws were made. Have to read this again in time, but it sounds like he started a huge and important reformation in greece that time 🤔

Downvoting a post can decrease pending rewards and make it less visible. Common reasons:

Submit

Thanks very much! Certainly is - me bloody fingers hurt from typing

Quite a few vital laws made, and a couple weird ones for sure, I'll be doing a blog on Cleisthenes sometime soon, and the implementation of democracy as we'd better recognise it today 👍🏼

Downvoting a post can decrease pending rewards and make it less visible. Common reasons:

Submit