Some of you may wonder how exactly Portugal was able to form and maintain independence, on a little corner of western Europe, over 800 years. That is what you are going to discover during this series of articles about the political history of Portugal.

In the last article, we left off on the political ascension of Henry as Count of Portugal, as his brother Raymond of Burgundy proved to be a weak military leader who was not able to contain the Almoravid’s offensive.

Alfonso VI giving ruleship over Portucale to Henry of Burgundy, 1096.

By Claudius Jacquand (1803-1878)L'Agence Photo RMN Grand Palais

Henry soon was shown to be a great military leader as well as a cunning political ruler. As such he secretly made an agreement with his brother, Raymond, that would divide the Leonese kingdom between the two, upon Alfonso VI’s death. This resolution was called the “Succession Pact.”, made in 1105, and having the support of the great Cluny monastic order, who, go figure, was French.

This Pact was the vivid result of the tension that was brewing in the Leonese court between the French Knights, who had recently gained considerable power, and the local Aristocracy. This last one supported the claim of Alfonso VI son, Sancho, who was born to a Muslim woman and was considered by the King as the rightful heir of the Leonese kingdom. Sancho was clearly a threat to Frankish influence.

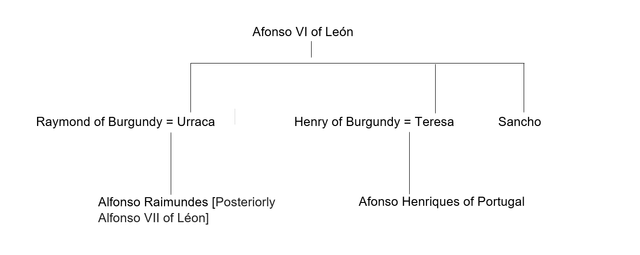

However, a series of events would hinder the brothers' plan. First, Raymond had a son with Urraca, daughter of Alfonso, by the name of Alfonso Raimundes who fundamentally changed the succession of Leon [See Image 2]. Then, a series of deaths would put a nail in the coffin of the Pact of Succession as Raymond died in 1107, followed by Sancho in 1108 and even Henry died in 1112. Ultimately, the Frankish influence in Iberia faded away as the Pact never came close to succeeding.

The sucession problem caused by Alfonso Raimundes, who became a legitimate claimant to the Leonese throne. After the death of Sancho we would, indeed, become the legitimate heir.

By War and Taxes, 2017

Nevertheless, Henry’s legacy in Portucale would be very significant as he successfully administrated the County, gathering the support of the Portucalensian Aristocracy and Clergy and conceding privileges to regions like Guimarães, Coimbra or Panoias (located in modern Vila Real) giving them “Cartas de Foral.” This piece of legislation was used by the Counts of Portucale, and later by the Kings of Portugal, to concede privileges and liberties to the different counties. The inhabitants of this region were then free of Feudal control and answered only to the king giving them a significant degree of autonomy. No wonder they would later be at the forefront of Portuguese economic development.

The empowerment of Portucale’s Barons would imbue a strong sense of regionalization that, in turn, contributed to a sentiment of independence towards Galicia and the Spanish Realms.

You see, after the death of Henry of Burgundy, his wife, Teresa, aligned herself with the Galician Family of the Travas, more precisely with Fernão Peres de Trava, that sought to remerge the County of Portucale with the kingdom of Galicia.

Henry of Burgundy and Teresa of Léon.

Source: The Portuguese Genealogy, Portugal (Lisbon), 1530-1534

As would be expected, the Portucalencian Nobles were not too happy about this, and when Fernão Peres de Trava established himself in Coimbra, in 1121, and started taking administrative actions, alongside Teresa, the most powerful Nobles completely halted political relations and stopped attending the County courts.

However, Henry had a son, Afonso Henriques, born in 1109, and who had proved himself a skilled military leader, as well as manifested his support for the political cause of Portucale’s Aristocracy.

Afonso Henriques managed to gather a strong base of support and, in 1128, the conflict reached a climax taking the two sides to open battle at São Mamede. Here Teresa’s army led by Fernão Peres de Trava faced the army of Afonso Henriques, who emerged victoriously. This victory marked Portucale’s independence from Galicia and paved the way for the formation of the Kingdom of Portugal.

Battle of São Mamede (1128)

By Acácio Lino

With freedom secured, Afonso Henriques moved his capital from Guimarães to Coimbra, not only to invigorate the “Reconquista” happening in the south but also to distantiate himself from the grasp of the aristocracy who had their power base north of the Douro river.

Soon, the young Portucalencian Ruler would initiate expansion of his dominions, building several castles in Leiria and Coimbra to help with the defense against the Muslim incursions and finally taking the offensive, in 1139, marching into to the Muslim lands, culminating in the Battle of Ourique. Once again Afonso would meet victory, after which we would start to entitle himself as “King of the Portuguese.”

Battle of Ourique (1143)

By Domingos Sequeira

Moreover, Afonso’s political affirmation would not stop there and, in 1143, he established a treaty known as Treaty of Zamora, who made his cousin Alfonso VII of León (Alfonso Raimundes for better understanding) recognize him as rightful king of Portugal. Furthermore, we would swear vassalage to the Pope Innocent II paying him an annual tribute of gold.

Treaty of Zamora on mosaic in Portimão.

Photo by: Aires Almeida"Tratado" by Aires Almeida on Flickr

His prestige would be increased even more by the great military successes he had against the Muslims in the south. The Almoravids were suffering from internal problems which led to the fragmentation of the Al-Andalus into several independent kingdoms starting the second Taifa Kingdom Period. The Portuguese King would capitalize on this fact and, as such, in 1147 conquered Santarem and Lisbon. Although he managed to capture Santarem on his "own", Lisbon was much harder to subdue. So, he took advantage of a passing armada of Crusaders, who were headed to Jerusalem for the Second Crusade, and enlisted their help in exchange for the sack of Lisbon.

Muslim surrender after the conquest of Lisbon.

By Joaquim Rodrigues Braga

With the Lisbon and Satarém, the line of the river Tejo was now secured and prompted the Portuguese King to seek further expansion of his realm. In 1165, Évora had fallen to Geraldo Sem Pavor, who acted much like a mercenary favoring whom he wanted, and who gave the city to Afonso Henriques. Later, in 1169, Geraldo would try to conquer Badajoz, asking for the King’s military help and promising to give him the city just like he did with Évora. However, the Muslim reinforcements backed by the Leonese King Ferdinand II, who felt threatened by the Portuguese expansion, delivered a heavy defeat to the Afonso’s army, putting an end to the King’s victories.

Portuguese borders after Afonso Henriques's conquests. In yellow the Portuguese territories, in brown the Leonese territories and in green the muslim territories.

From: Imagem: Portugal em 1185

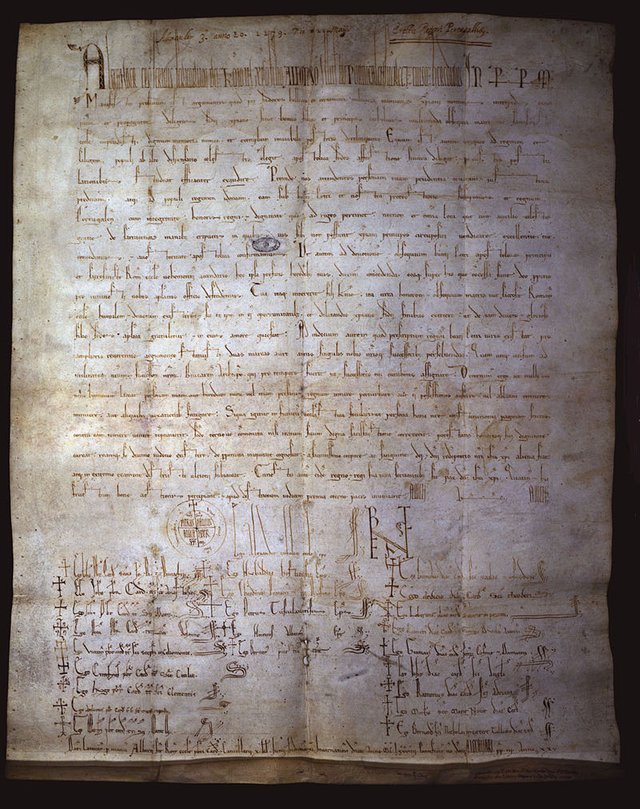

Before his death in 1185 Afonso would further legitimize his rule as Pope Alexander III, in 1179, granted the “Bula Manifestis Probatum” who finally acknowledged him as King.

Bula Manifestis Probatum 1179

After this, there was no doubt that the Portuguese Kingdom was here to stay, but now it was the turn for Afonso’s successor, Sancho I, to defend the hard-gained independence.

Buy books of Portuguese History here:

Sources:

Mattoso, J. (1997). História de Portugal - Antes de Portugal. Lisboa: Editorial Estampa. ISBN 972-33-1261-1

Rui Ramos, B. V. (2009). História de Portugal. Lisboa: A esfera dos livros. ISBN 978-989-626-366-9

Disclaimer: This is a repost of an article you can found on my personal blog https://warandtaxes.wordpress.com/.

Hi! I am a robot. I just upvoted you! I found similar content that readers might be interested in:

https://warandtaxes.wordpress.com/2017/06/28/political-history-of-portugal-2/

Downvoting a post can decrease pending rewards and make it less visible. Common reasons:

Submit