– how the emergence of agriculture transformed the Nomad into a Settler and birthed civilisation.

image source

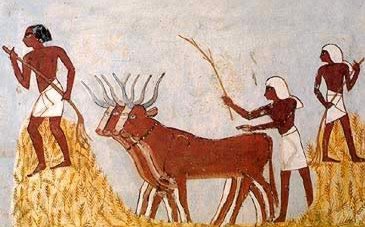

The so-called Neolithic Revolution(1) began for Homo sapiens sapiens around 12,000 years ago. For many centuries they had lived as small tribes in pockets of the world, as nomadic hunter-gatherers, to flow with the changing natural rhythms of their world. But something changed – scientists, historians, anthropologists, botanists, archaeologists are all still debating what – and man began to develop a different system of living – that of agriculture. The conscious manipulation of their food sources for cultivation and breeding. This change in direction eventually led to the birth of civilisation – a more complex system of cultural development, and the basis of what we have today.

According to Charles Darwin, the ‘preeminent force behind the domestication of plants and animals’(2) started off as Unconscious Selection, which then led to Methodical Selection, and the systems we use today without second thought. Unconscious selection became a natural progression of the Neolithic people, utilising the flora and fauna which best aligned with their lifestyle, and either ignoring or destroying that which didn’t. Its goal was for immediate results, unlike the far more sophisticated methodical selection plan for long-term manipulation of agriculture, to suit human plans and needs. Trial and error would have played a large factor in which direction/s development went. The choosing of which animals to domesticate would have come from their feeding habits, controllability, adaptability, and reproductive success, as well as what they could be utilised for – meat, milk, skin and fur. With plants it was fairly similar – adaptation, reproduction, survival, harvest yield, storage, pest-resistance, and utilisation into food.

image source

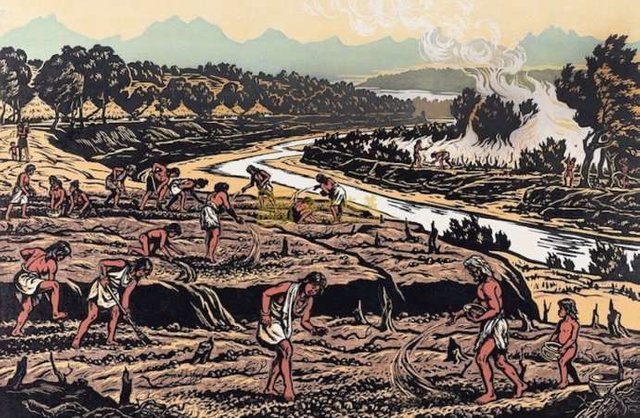

Archaeological evidence shows that the emergence of agricultural practices was developed in pockets of nomadic civilisation around the world, independently, but in similar ways. Along with the evolvement of the human species came a more focused awareness of their being able to manipulate their surroundings to better suit the tribe. Whether this was actually a natural (passive) evolutionary progression, or forced (active) for the human species or not is a point of debate by many scholars. One theory came from looking at the male-female roles in society, speculating that as the female role was to gather, she began to nurture the food plants and then actively cultivate them.

“On the whole then, it appears highly likely that as a consequence of a certain natural division of labor between the sexes, women have contributed more than men towards the greatest advance in economic history, namely the transition from a nomadic to a settled way of life, from a natural to an artificial basis of subsistence.”(3)

Although, the question of just why these nomadic hunter-gatherers turned to a sedentary lifestyle is still an unanswered question amongst scholars, with an interesting variety of theories expounded.(4) The ‘Neolithic Age’ is not a chronological marker in history, but rather denotes a change in behaviour and culture, with the domestication of not only plants and animals, but man himself. After travelling along for thousands of years as someone who followed, he was now taking control and leading the way, establishing man as the master manipulator. Once a slave to the rhythms of nature and her cycles, man could now control at least a portion of the ecosystem for his own benefit. “Domestication was the invention that made populous and complex human societies viable. It has thus proved to be the single most important intervention man has ever made in his environment.”(5) This development was the key which firmly established humans at the top of the food chain. Humans being the only species which manipulates its food supplies – and the surrounding environment - so thoroughly, and on such a large scale. Once the farmer’s immediate surroundings were producing for him, he started extending his territory. This meant the clearing of trees, building irrigation systems, terracing mountainsides – basically turning formerly unproductive areas for humans into useful ones.

image source

Careful studies of evidence found through numerous archaeological excavations - food, tools and housing - have built up a picture of where, when, and what was going on, as these nomads became sedentary. The oldest evidence researchers have found has been from around 10,000 B.C.E, in the Middle East.

“The Fertile Crescent of Western Asia, Egypt, and India were sites of the earliest planned sowing and harvesting of plants that had previously been gathered in the wild. Independent development of agriculture occurred in northern and southern China, Africa's Sahel, New Guinea and several regions of the Americas. The eight so-called Neolithic founder crops of agriculture appear: first emmer wheat and einkorn wheat, then hulled barley, peas, lentils, bitter vetch, chick peas and flax.”(6)

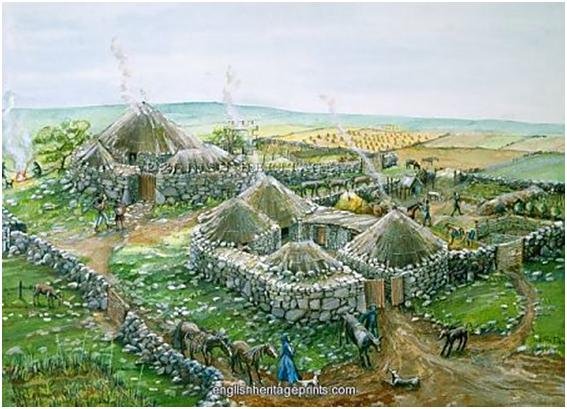

This agricultural manipulation of the surroundings allowed for the establishment of a non-nomadic lifestyle for many tribes. Permanent – as much as the materials would allow – structures were built – houses, granaries, animal shelters. It became – albeit very slowly – a snowball effect, with a settled tribe attracting greater numbers, partly from increased births and partly by other tribes wishing to join the collective. Soon these greater numbers established villages, which developed more diverse skill sets, including crafts and trading of excess produce. Some of these villages morphed into towns, with a number of those swelling even further and becoming far more complex systems of culture - cities. Thus we see many levels of civilisation created from the first seeds of an early agrarian establishment. No matter how large these dense areas of population became, they all still had in common the fact that they relied on the primary industry of agriculture for many basic needs, as we still do today.

Chysauster, a village near Penzance in Cornwall, England

image source

The less a tribe had to forage for their food, the more they could increase their numbers – partly because they could grow and store greater quantities of food, and partly because they did not have to be travellers, with minimal gear. Settling in areas which had the best climates for production was a sensible move – lush plant growth attracted more grazing animals and therefore more game, and larger crops, to eat. Once the tribe began to have excesses of food and products they began to trade with other tribes. This led to wealth for people, which in turn proved an attraction for more members to move into, or near, the tribe, thus building up the number of members and producers. Trade also produced diversification. People could trade for something they could not grow, make or otherwise gain from their own backyard. Folk began to specialise – perhaps they only traded in furs, cloth and garments, or became horse-traders. Artisans developed crafts like pottery and jewellery, also able to be traded. With the domestication of animals such as horses, donkeys and cattle people were able to harness their greater strength, using them in the fields with ploughs; and they were now able to travel greater distances. This allowed them to settle in new areas, trade further afield, even make war against other tribes – both to gain more resources and stave off attacks on themselves. The invention of tools to help in agricultural work, and the follow-on of metallurgy led to the making of weapons. Combined with being on horseback, this led some tribes to easily overpower and conquer others, thus gaining both territory, resources, and people for themselves.

Once towns had fairly large populations they needed ways of controlling the people and allowing an orderly fashion to daily life. Different cultures developed various systems of councils or governing bodies to oversee the folk. With wealth, along came prestige and tribal clout for some members. These were the people who became the leaders, and eventually, within some tribes, their power became hereditary. Other cultural systems began to slowly develop, becoming more complex as time went on. Ceremonies, rituals and sacrifices to gods, as a way of continuing good harvests developed. Skills increased and new products were made – such as weaving, for clothing and blankets. Primitive forms of writing were developed, both for communication and record-keeping. Static societies also experienced negative developments, such as diseases brought on by close quarters, bad hygiene, and cross-contamination with animals. They also finally realised that planting the same crops in the same ground year after year diminished the success of growth and harvest - new systems had to be developed or they risked starvation. Warding off wild animals and other tribes would also have been a major task.

Babylonian cuneiform script on a clay tablet, cir. 1200BC

image source

Out of problems came solutions, inventions, and more growth, until previously disjointed pockets of people evolved into civilisations. Once unoccupied territories were expanded into, trade routes established, monetary systems developed, governments created, boundaries drawn up, and people united in their quest for survival. Towns and cities could now be developed in less agrarian-supportive areas, thanks to the growth of trade. If a town did not have a close supply of timber, for example, it could trade for it with a town that did; excess food eagerly bought and sold. Competition for the wealth and power of land and produce became fierce – people now had to learn how to either fend off an attack or become the aggressor. Protection was another reason to seek out, and ally with, others. We now had completely different situations from when man was a nomadic hunter-gatherer. No longer largely independent, living in small groupings, he was part of a much larger social culture. Although the basic needs for survival never changed, the imprint of man on his surroundings, and the development, the pace, and the direction of life on the planet, had changed forever.

This essay was one I wrote as an assignment, while obtaining my University degree. I have included the reference list and bibliography - reference materials I used while writing - just as I’d had to for its submission. It has never before been published anywhere public, though. Images have been added for visual interest.

Endnote & References:

1 “The term Neolithic Revolution was coined in the 1920s by Vere Gordon Childe to describe the first in a series of agricultural revolutions in Middle Eastern history. The period is described as a "revolution" to denote its importance, and the great significance and degree of change affecting the communities in which new agricultural practices were gradually adopted and refined.” Retrieved 17 December 2009, from: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Neolithic_Revolution

2 Rindos, David. The Origins of Agriculture: An Evolutionary Perspective. Orlando: Academic Press, 1984, p 2, para 1.

3 ibid., p 10, para 1.

4 Agricultural Transition. Neolithic Revolution, retrieved 17 December 2009, from: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Neolithic_Revolution

5 Isaac 1970:1 as quoted in David Rindos The Origins of Agriculture: An Evolutionary Perspective. Orlando: Academic Press, 1984, p 5, para 2.

6 Agriculture, retrieved 17 December 2009, from: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Agrarian

Bibliography:

Agriculture, retrieved 17 December 2009, from: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Agrarian

Bentley, Jerry H., Herbert F. Ziegler, Heather E. Streets. Traditions and Encounters: A Brief Global History. New York: McGraw-Hill, 2008

Burenhult, Goran (ed.). People of the Stone Age: Hunter-gatherers and Early Farmers. Queensland: University of Queensland Press, 1993

Chadwick, Robert. First Civilizations: Ancient Mesopotamia and Ancient Egypt. (second ed.) London: Equinox Publishing, 2005

Clutton-Brock, Juliet. A Natural History of Domesticated Mammals. London: British Museum, 1987

Clutton-Brock, Juliet. Horse Power: A History of the Horse and the Donkey in Human Societies. London: Natural History Museum Publications, 1992

Frank, R. I. (trans.). The Agrarian Sociology of Ancient Civilizations. Verlag J. C. B. Mohr. London: NLB, 1976

Howe, Timothy. Pastoral Politics: Animals, Agriculture and Society in Ancient Greece. California: Association of Ancient Historians, 2008

Isager, Signe, Jens Erik Skydsgaard. Ancient Greek Agriculture: an introduction. London: Routledge, 1992

Jarman, M. R., G. N. Bailey, H. N. Jarman, (eds.) Early European Agriculture: Its Foundations and Development. Bath: Cambridge UP, 1982

Leonard, Jonathan. The Emergence of Man: The First Farmers. USA: Time Inc., 1974

Membrez, James H. (trans.) A History of Wold Agriculture: From the Neolithic Age to the Current Crisis. Marcel Mazoyer, Laurence Roudart. New York: Monthly Review Press, 2006

Oppenheim, A. Leo. Ancient Mesopotamia: Portrait of a Dead Civilization. Revised edition completed by Erica Reiner. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 1977

Piggott, Stuart. Ancient Europe: from the beginnings of Agriculture to Classical Antiquity. Edinburgh: Edinburgh UP, 1965

Rindos, David. The Origins of Agriculture: An Evolutionary Perspective. Orlando: Academic Press, 1984

Smith, Bruce D. The Emergence of Agriculture. New York: Scientific American Library, 1995

You received a 60.0% upvote since you are a member of geopolis and wrote in the category of "geopolis".

To read more about us and what we do, click here.

https://steemit.com/geopolis/@geopolis/geopolis-the-community-for-global-sciences-update-4

Downvoting a post can decrease pending rewards and make it less visible. Common reasons:

Submit

Living in an agricultural area in a small town it is amazing to see how little has changed between the emergence of agriculture and now, save for the mechanization and sheer scale of it all. They still have the same problems, but they do have better solutions. The basic idea of agriculture has been unchanged for close to 10k years now. Makes you think about it a bit.

Downvoting a post can decrease pending rewards and make it less visible. Common reasons:

Submit

When you put it that way, it certainly does. :)

Downvoting a post can decrease pending rewards and make it less visible. Common reasons:

Submit

This is a curation bot for TeamNZ. Please join our AUS/NZ community on Discord.

For any inquiries/issues about the bot please contact @cryptonik.

Downvoting a post can decrease pending rewards and make it less visible. Common reasons:

Submit

Good job friend and pic

Downvoting a post can decrease pending rewards and make it less visible. Common reasons:

Submit

Thank you. Which pic did you like the most? And why? I did spend a long time hoping to find just the right one.

Downvoting a post can decrease pending rewards and make it less visible. Common reasons:

Submit

Great article. Such an interesting course of evolution for all of us. Partly I feel incredibly nomadic to my core and I wonder if the DNA is still pointing us in that direction.

The resulting overpopulation & exploitation of resources to the point of systemic collapse is obviously an incredibly negative side effect of this way of life. It’s interesting to ponder!! The rewilding communities that spring out of these realizations often promote the awareness of quite practical skills & communal patterns for humanity. Wonder if we’ll continue seeing a resurgence of this rewilding way of life as more people “wake up” to the effect humans are having. I think it’s likely 🍀💚

Downvoting a post can decrease pending rewards and make it less visible. Common reasons:

Submit

I imagine you're quite right in your prediction of a continuing resurgence. More and more people are dissatisfied with 'the norm' and hungering for something better - and what is more powerful than our basic roots?

Perhaps this is a case of the pendulum swinging slowly back through, to counterbalance this fast-paced technological world ... :)

Downvoting a post can decrease pending rewards and make it less visible. Common reasons:

Submit

What can I say¿ Well constructed and informed essay. I enjoy reading your episodes of history. Thank-you for that. Keep on keeping on. 😇

Downvoting a post can decrease pending rewards and make it less visible. Common reasons:

Submit