“The elephant cannot fight the whale but we must find a means to subdue the sea to the land.” – Napoleon Bonaparte1

image source

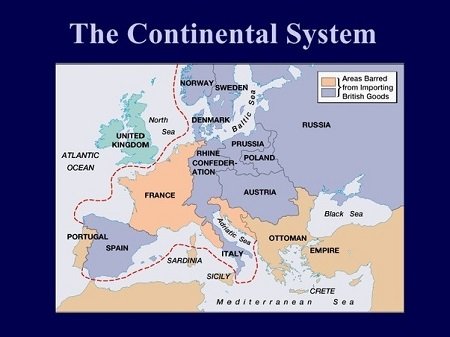

The Continental System was devised and implemented by Napoleon as a way for France to strike back at one of her enemies by the means of containing and controlling Britain’s economy; of stifling her international trade and commerce by blocking port access and punishing those who traded with her. Not only did The Emperor put in place bans from within his own country to trade in any way with Britain, but if any other nation did any form of trade with, or used Britain’s ports in any way, then they too were placed under the same embargoes. After France’s humiliating defeat at sea during the Battle of Trafalgar of 21 October 1805 by Britain, Napoleon looked to alternative means of scoring a victory over his enemy, and an economic superiority must have seemed very appealing. Stifling a country’s trade and commerce was more likely to have had more effective far-reaching effects than a military win could produce.

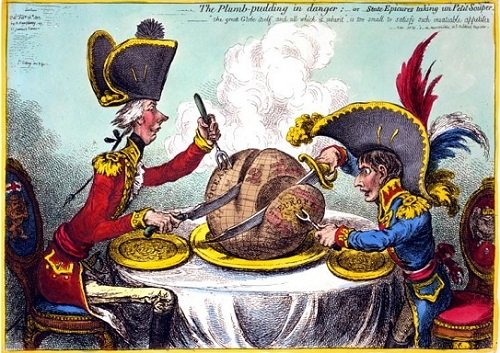

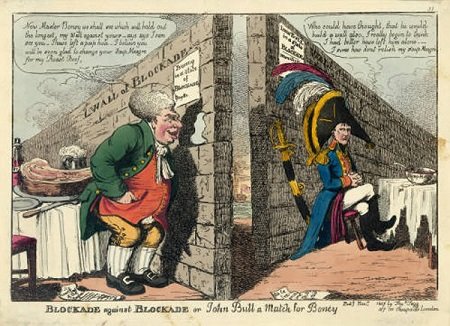

William Pitt and Napoleon depicted in a satirical cartoon from 1805

image source

Unfortunately for Napoleon’s plan, Britain remained a dominant force on the sea, which further aided her in a faster, more brutal development of industrialisation than France experienced, being able to not only tap into a base of internationally-found primary resources such as coal and iron ore, but build up an international trade of manufactured goods industrialisation then allowed them to produce, accompanied by the efficient and cost-effective method of transporting those goods to market by sea. Economic, political, military, demographic, resource and cultural divergence set France off on a different path of development than her European neighbours, unintentionally allowing industrialisation to happen less brutally than other countries, especially Great Britain, experienced.

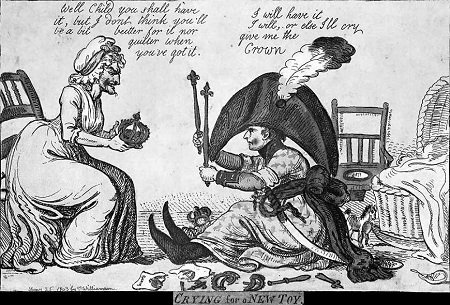

Napoleon's actions inspired many satirical and caricature-style cartoons

image source

Napoleon, when he came to power, inherited the basic structure and ideology of a ‘strongly protectionist’ commercial policy created by the old regime during the revolution. As early as 1796 measures had been taken to stifle English international trade, with the Loi de 10 Brumaire, An V.2 The ‘rigid protectionist doctrines’ had been held by ‘the men of the Terror in 1793, by the Directory in 1796, [and] by the overwhelming majority of the French people in 1798’,3 so while Napoleon was not the primary instigator of such a policy of commercial isolation, he continued forward from the groundwork laid by previous administrations, and refined the overall structure it would take – or what he hoped it would take.

Blockade of Toulon, 1810-1814: Pellew's action, 5 November 1813, by Thomas Luny

image source

The Berlin Decree of 1806, which formed an early part of what would come to be known as the Continental Blockade, was the first definitive step in Napoleon’s plan to cripple Britain financially. It is possible that the earlier policies contributed in some manner towards the ‘less brutal’ industrial growth in France once the Emperor’s plan was implemented, with the protectionist attitude not exactly being a fresh concept for the business people of France to have to adjust to. Napoleon’s empirical policies saw, and encouraged, the ‘formation of large vertically integrated firms, usually family operated or directed by limited partnerships’,4 which would have been a discouragement to large-scale expansion for most businesses. Unlike in Britain, where the industrialists formed companies and grew into large enterprises with shareholders and stocks, the businessmen of France were encouraged to remain smaller, more intimate and family-based – a more nuclear structure. This would have limited the growth and expansion of a business, as well as the number of employees it could take on. But even if these businesses had wanted to expand and grow into giant industries, such as seen in Great Britain, then the very policies implemented by Napoleon would have stifled their chances of success, and one major factor in this was the self-imposed lack of access to necessary raw materials found overseas.

Embargo, by Alexander Anderson, reflecting a hostile reaction to the Embargo Act of 1807

image source

Napoleon must have believed that with the acquisition of at least several of his newly-annexed Continental European countries he had access to enough resources to remain independent of any reliance on the British, or her allies, for the foreseeable future. Belgium had great coal deposits and the Rhineland had large reserves of iron ore, essential in any industrial enterprise at the time. What he had likely not taken into account was the significance of the type of goods France was producing as opposed to what Britain had to offer. The British, without French silks, adapted to using wool and cotton – two commodities British industries were quickly utilising – whereas the Continental System ‘cripple[d] the resources of France’5 and Napoleon’s efforts ‘deprived the manufacturers in his own lands of all their raw materials’.6

Cartoon from 1812 showing Columbia (the United States) warning Napoleon I that she will deal with him after teaching John Bull (England) a lesson.

image source

This self-imposed isolation proved to be a difficult and frustrating time for French producers. According to one historian, the French Revolution was to blame, for being ‘catastrophic and disruptive’, setting back France’s economic growth significantly. Continued military endeavours led by Napoleon would have added to the financial set-backs of France, with much resource being fed into military needs rather than economic needs. For example, Napoleon hastily sold off Louisiana in North America as he felt war was imminent and he needed the funds to continue his military endeavours, but Louisiana could have supplied French manufacturers with cotton, in opposition to the British who were purchasing some of their bulk cotton from other producing southern states in North America. Several of the countries who had aligned themselves with Napoleonic France became very unhappy about being cut off from the luxury items inaccessible to them through the trade embargo, and reopened their borders to international trade, much to Napoleon’s frustration. However, because of its self-imposed isolation, France was spared the rather brutal industrial revolution which occurred in other countries, especially Britain.

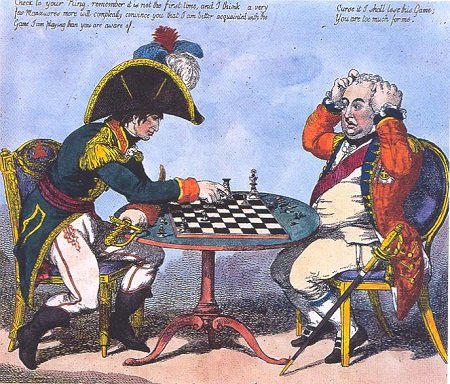

Cartoon of Napoleon playing chess against Cornwallis

image source

While Britain’s industrialisation experienced rapid development, brought on mainly by her large coal deposits, mastery on the sea and access to international trade, France’s progress came via other routes, so the effects on her people were rather softer but still nonetheless effective in the end. According to Lévy-Leboyer, while ‘coal and iron were more expensive’ than in other countries, wages were lower and France had a skilled labour force, which led them to turn to more ‘labour-intensive, quality, fashion and luxury goods’7 which they would then later industrialise. Lévy-Leboyer showed that the French industrialists had invented ‘new products and new fashions’ rather than ‘new machinery’. He also pointed out that the ‘great majority of French businesses were family affairs’8 although that did not hold them back from experiencing vigorous growth as successful enterprises.

Cartoon mocking the blockade

image source

Another reason for slow industrial growth was with having had the wealthiest level of society - the aristocracy - much destroyed during the Revolution, and its wealth either destroyed or confiscated, there would have been a much smaller base of potential investors or developers from which to put capital funding into developing industrial enterprise throughout France. Another large financial setback to French industrial development was that her post-war reparations were a great economic strain. The war indemnity after the Battle of Waterloo had been calculated as creating a ‘lasting negative impact upon growth’ and after the Franco-Prussian war, large reparations were estimated to have ‘caused the loss of 8 per cent of French industrial capacity’.9 Separately, each financial loss would have been hard enough to recover from, but combined they would have proven crippling to any country’s economic growth. Another setback came through the massive losses of life which originated from both the Revolution and the Napoleonic wars.

peasant family, artist unknown

image source

Population growth was slow after both the Napoleonic wars and the French Revolution had taken a large toll on family numbers; this was another example where separately the long-term implications were affecting enough, but combined they formed a much larger obstacle. Also, birth control was being practiced throughout France at this time.10 As a result, this affected her GDP per caput. If she had experienced a substantial population growth at this time, it is possible – even likely – that France would have experienced the same brutal overcrowding, poverty and illness that industrial Britain had; so perhaps French people developed a healthier society as they eased into their industrial era, rather than having to go through more shocking changes within their social strata.

landscape, artist unknown

image source

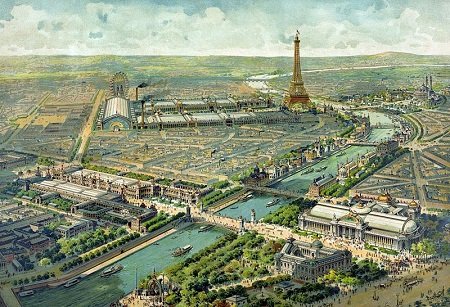

Another contributor to her very different development in comparison to Britain was that France remained a more peasant-based rural society, without the great migration to towns and cities; people stayed in their traditional, labour-intensive agriculturally-based jobs, their social structure remaining virtually unaltered. According to historian Patrick Verley, France “managed to avoid the enormous social cost of British industrialization”.11 Britain had indeed incurred an enormous social debt, as rural people migrated into towns and cities for work they put great strain on housing, resources and amenities, with the result being much overcrowding, poverty and disease, long working hours, and a shift in traditional family and social structures. France’s experience during her own industrialisation was certainly not that brutal. Indeed, analysts have observed that perhaps ‘France had a more humane and perhaps a no less efficient transition to industrial society’.12 It is only within the last several decades that analysts and historians have begun to look differently at how France performed in comparison to other countries, with France being looked at more favourably for her overall performance, rather than making direct comparisons between areas such as industrial growth in Britain, France, Belgium, Russia, for example. This new ‘revisionist’ attitude has begun to show that France was perhaps a quiet achiever, her successes merely overshadowed by the industrial giant, Britain.

This caricature shows John Bull, symbol of the average Englishman, gloating because his blockade is causing food shortages in France

image source

Without the incentive of international competition to put pressure on research and development, France had less momentum than Britain to industrialise. Britain led the way because of her access to primary resources such as coal, which led to the development of steam-driven engines which many factories began to utilise. France did not have the same primary fuels, and although several of the countries she had post-war control over like Belgium were rich in coal deposits, before the invention of the steam-engine there would be no railroad by which to transport vast quantities of resources back to France for her to build up industries.

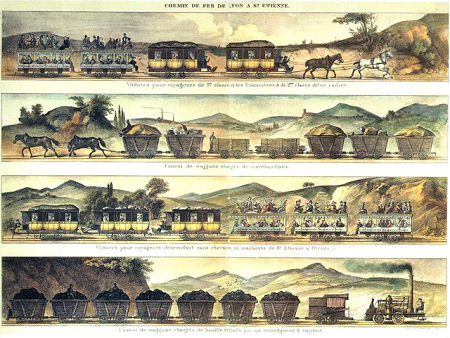

The history of rail in France

image source

It wouldn’t be until the mid-nineteenth century that an European railway system would develop, and make large-scale industrialisation practical. Perhaps she even observed what was happening in other countries and made adjustments with political strategies for her own country accordingly, thereby bypassing the more brutal consequences of industrialisation happening elsewhere. Although this came about long past Napoleon’s time, and possibly it happened more despite him rather than because of him, it appears to be that in all major areas France’s economic, political, military, demographic, resource and cultural divergences indeed did set her off on quite a different path of industrial development than her European neighbours – especially Great Britain - experienced, and therefore unintentionally allowing industrialisation to happen for France less brutally, while in the long-term still achieving a high level of industrialisation on a par with other leading nations.

industrialised France

image source

This essay was one I wrote as an assignment, while obtaining my University degree. I have included the reference list and bibliography - reference materials I used while writing - just as I’d had to for its submission. It has never before been published anywhere public, though. Images have been added for visual interest.

References:

1 Tonge, Neil. Industrialisation and Society, 1700-1914. Challenging History. np: Nelson Thornes, 1993, pp. 188.

2 Sloane, William M. "The Continental System of Napoleon." Political Science Quarterly 13.2 (1898) pp. 214.

3 ibid., pp. 217.

4 Horn, Jeff. The Path Not Taken: French Industrialization in the Age of Revolution, 1750-1830. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2006, pp. 224.

5 Sloane, William M. "The Continental System of Napoleon." Political Science Quarterly 13.2 (1898) pp. 231.

6 ibid., pp. 230.

7 Crouzet, Francois. "The Historiography of French Economic Growth in the Nineteenth Century." The Economic History Review, New Series 56.2 (2003) pp. 225.

8 ibid., pp. 225.

9 ibid., pp. 235.

10 ibid., pp. 237.

11 ibid., pp. 229.

12 ibid., pp. 227.

Bibliography:

Bergeron, Louis. France under Napoleon. Trans. Palmer, R. R.: Princeton UP, 1981. Print.

Crouzet, Francois. "The Historiography of French Economic Growth in the Nineteenth Century." The Economic History Review, New Series 56.2 (2003): 215-42. Print.

Davies, Norman. Europe : A History. London: Pimlico, 1997. Print.

Dwyer, Philip G., ed. Napoleon and Europe. New York: Longman, 2001. Print.

Englund, Steven. Napoleon: A Political Life. Harvard UP, 2005. Print.

Horn, Jeff. The Path Not Taken: French Industrialization in the Age of Revolution, 1750-1830. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2006. Print.

Lyons, Martyn. Napoleon Bonaparte and the Legacy of the French Revolution. European Studies. revised ed. Vol. 1: Palgrave Macmillan, 1994. Print.

Ragsdale, Hugh. "A Continental System in 1801: Paul I and Bonaparte." The Journal of Modern History 42.1 (1970): 70-89. Print.

Rose, J. Holland. "A Document Relating to the Continental System." The English Historical Review 18.69 (1903): 122-24. Print.

Sloane, William M. "The Continental System of Napoleon." Political Science Quarterly 13.2 (1898): 213-31. Print.

Tonge, Neil. Industrialisation and Society, 1700-1914. Challenging History. np: Nelson Thornes, 1993. Print.

(extra tags: #geopolis #france #napoleon #culture #minnowsupport)

This is a curation bot for TeamNZ. Please join our AUS/NZ community on Discord.

For any inquiries/issues about the bot please contact @cryptonik.

Downvoting a post can decrease pending rewards and make it less visible. Common reasons:

Submit

Hey @ravenruis thanks for that. It was a pretty interesting post. keep it up.

Regards @run.vince.run

Downvoting a post can decrease pending rewards and make it less visible. Common reasons:

Submit

I'm very happy you enjoyed it. :)

Downvoting a post can decrease pending rewards and make it less visible. Common reasons:

Submit