Film discourse largely agrees on the classification of either Hook (1991) or 1941 (1979) as the least-liked Spielberg film. When the director’s work is discussed by whatever self-proclaimed expert – myself included – these two titles are usually at the bottom of the list. But there is another Fantasy film in Spielberg’s oeuvre that often is not even mentioned at all – Always (1989).

Over the years, I’ve noticed that the films of Hollywood’s most successful and recognizable director neatly fall into three specific categories – Spielberg Serious, Spielberg SciFi and Spielberg Sunny.

Spielberg Serious features work like Schindler’s List (1993) and Munich (2005), films about important historic events that usually generate lots of Oscar buzz. Spielberg SciFi (or Fantasy) is where the director really flexes his creative muscle and produces epic blockbusters like Jurassic Park (1993) and Minority Report (2002). And Spielberg Sunny sees the bearded one at his most lighthearted, with lovely features like Catch Me If You Can (2002) and The Terminal (2004).

Naturally, some of Spielberg’s films defy classification. E.T. the Extra-Terrestrial (1982), for example, is an obvious combination of Spielberg SciFi and Spielberg Sunny, as is the aforementioned Hook. And where to place the remake of West Side Story (2021)? Spielberg Singing?

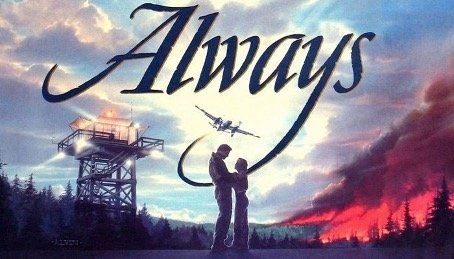

Always, the Spielberg film nobody remembers, also drifts between the director’s Fantasy and Sunny disposition. The story of an aerial forest-fire fighter (Richard Dreyfuss) who (spoiler) dies in the line of duty and, as a guardian angel, tries to mentor his great love (Holly Hunter) through pivotal life decisions, is a loose remake of the classic film A Guy Named Joe (1943) starring Spencer Tracy.

Appreciating a film is like falling in love. It’s difficult to explain to other people why you like a particular person, you just do. In Robert Zemeckis’ seminal SciFi epic Contact (1997), Jodie Foster’s atheistic scientist questions Matthew McConaughey’s belief in God because he can’t prove His existence. He retorts by asking her to prove that she loved her deceased father. Visibly shaken, she of course can’t. It was an eye-opener for me. I had never thought of such a satisfying and reassuring approach to these impossible to answer questions.

What made me fall in love with Always – aside from my adoration of the SciFi and Fantasy genres – was the superb onscreen coupling of Dreyfuss and Hunter. I have always found the “everyman” quality of Dreyfuss appearance very appealing. He is someone you can easily identify with, in stark contrast to, say, Paul Newman or Robert Redford, who Spielberg originally had wanted for the film. Don’t get me wrong, Redford and Newman are of course fantastic actors, but they are just too good-looking – sorry Richard…

I feel the same way about Hunter. I mean, I think she is a beautiful woman, but also exactly right for the part. She, like Dreyfuss, looks like someone you could run into while walking down the street. If Spielberg would have cast Julia Roberts in the role, the focus of the film would have been too much on her as a celebrity. Actors who are also “Movie Stars” just don’t feel right for this story, they would be too distracting.

Dreyfuss and Hunter would reunite two years later for Lasse Hallström’s underrated gem Once Around (1991) and again prove to be the perfect duo for an honest, unpretentious love story. There is something about their combined performance that makes it relatable and therefore more credible.

Full disclosure in the spirit of the No. Bad. Films. Philosophy – these comments about Dreyfuss’ and Hunter’s levels of attractiveness and popularity are my personal opinion, not a statement of fact. Also, years later Roberts herself would of course put a wonderful spin on the Celebrity / Movie Star / Everyman notion in the fantastic RomCom Notting Hill (1999).

Rounding out the main cast is the always awesome John Goodman. I rank Always as my favorite Goodman performance, but it is a close finish with King Ralph (1991) and The Big Lebowski (1998). The jolly giant is firing on all cylinders in Always, giving a multi-layered performance that is a step above his usually more broadly comedic work. Which is not to say that Goodman isn’t funny in Always. One scene has Dreyfuss’ guardian angel Pete Sandich trick Goodman’s Al Yackey into swatting an imaginary fly on his face. Moments before however, Pete observed Al shake someone’s oil-smeared hand without noticing it. Slapping away at a bug that isn’t there, Al’s face is soon covered in black goo. The chemistry between Goodman and Dreyfuss is so obvious that it makes me very hungry for more team ups of the two actors, which I don’t think has happened since.

A curious addition to the cast is Brad Johnson, a before and since almost unheard-of actor. Johnson plays Ted Baker, the rugged pilot who makes Hunter’s Dorinda believe in love again after the devastating loss of her soul mate Pete. Between the otherwise nearly pitch-perfect ensemble of actors, Johnson almost feels like an afterthought. He looks the part, sure, but to me his performance has always felt a bit uneasy and awkward. Like he was not really part of the fun the others were having in making the film – again: opinion.

A beautiful, beautiful cameo in Always is bestowed on us by formidable Audrey Hepburn in what was to be her final performance. The legendary actress is Hap – what’s in a name – the “Grand Angel” who eases Pete into his acceptance of death and his responsibilities in the afterlife. Spielberg originally wanted Sean Connery for the part, but recast the role for a woman when Connery proved unavailable. In true cameo tradition, Hepburn donated her entire salary of a million dollars to charity. The following year Connery would do the same with his fee for cameoing in Robin Hood: Prince of Thieves (1991), perhaps the film he was busy making when he turned down Always. Completing this circle is Richard Lester’s Robin and Marian (1976), in which Hepburn and Connery starred together. Everything is connected.

Among the people behind the camera are also some pretty impressive names. During the first twenty years of his feature filmmaking career, Spielberg hadn’t yet found his steady cinematography-muse Janusz Kaminski, who lensed every single one of the director’s films since Schindler’s List (1993). Spielberg’s first 15 features saw him teaming up with several different camera Gods like Vilmos Zsigmond, Allen Daviau and Dean Cundey. For Always, the director chose the Swedish filmmaking legend Mikael Salomon to frame the story. Salomon had only just begun lensing films in The States and had hit the ground running. In a single year he not only helped Spielberg bring Always to life, but also shot the underwater epic The Abyss (1989) for James Cameron. Let’s just say the cinematographer made quite a splash with his first steps in Hollywood.

The extensive aerial sequences in Always were designed and executed by Joe Johnston, future director of The Rocketeer (1991) and Captain America: The First Avenger (2011). The strong bond the two filmmakers formed during the making of Always continued over the years that followed, given that Spielberg trusted Johnston with the keys to the Indiana Jones and Jurassic Park kingdoms – Johnston directed Jurassic Park III (2001) and several incarnations of a Young Indiana Jones TV series.

A lovely detail in Always is the song Spielberg chose for the scene that shows Pete and Dorinda having an intimate slow dance at their local watering hole. Like everything else in Always – except for maybe Brad Johnson – “Smoke Gets In Your Eyes” by The Platters just fits the mood of the film like a glove. The soundtrack selection is also an example of the wonderful side effects some films can have. When I was a 13-year-old and saw Always for the very first time, I had no idea who The Platters were and why smoke would get in their eyes. The film made me fall in love with the song though, and I listen to it regularly to this day. Not to mention that it is quite an apt ballad for a story about firefighters…

As the years progress, one picks up knowledge and information along the way that helps grasp life’s existential ponderings. When I first saw Always, I didn’t give much thought to the afterlife element, I viewed it as just a typical convention of the Fantasy genre. Not to long ago however, I learned about an idea that the Japanese call “Shoji”. In essence, Shoji are the paper-thin, almost transparent sliding doors we see in most Japanese homes. But the more spiritual definition of Shoji is that life and death are also only separated by an almost translucent divide. The people we lost are on the other side of that thin sheet and if we are receptive to it, we can still see them. Always, but also films like Meet Joe Black (1998) and The Sixth Sense (1999), are beautiful variations on this comforting philosophy.

The idea of death being like a slightly transparent door really appeals to me. It’s only natural, I guess. After all, we are all looking for looking for answers and meaning to life’s existential mysteries. Some find it in religion, others unsuccessfully look for enlightenment in a bottle or needle. My faith has always been in films, and my soul is richer because of it.

#thescreenaddict

#film

#movies

#contentrecommendation

#celebrateart

#nobodyknowsanything

Twitter (X): Robin Logjes | The Screen Addict