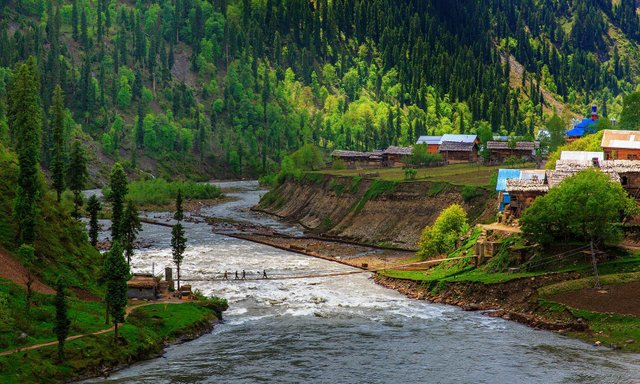

One of the most popular Pakistan beautiful places is Neelum Valley. This densely forested area is found in the Azad Kashmir region. Mughal Emperor Humayin once said about this Kashmir area that “if there is a paradise on earth, then this is it.” Visitors usually agree with his well-spoken assessment of the Kashmir Valley today.

The stunning valley sits at a high elevation of more than 4,850 feet (or 1,650 meters high) above sea level. Incredible milky white-colored waterfalls cascade from the mountains and provide the natural scene with a mesmerizing quality and otherworldly backdrop.

Tourists and locals alike come from all across Pakistan to see this glorious wonder of nature that is impossible to discount as a serious contender for the most beautiful spot on earth.

My driver and I drove by the Line of Control as we passed through an area opposite to the Keran sector of Indian-held Kashmir. From the Chella Bandi Bridge – just north of Azaad Kashmir’s capital Muzaffarabad – to Tau Butt, a valley stretches out for 240 kilometres; it is known as the Neelum Valley (literally, the Blue Gem Valley).

Neelum is one of the most beautiful valleys of Azaad Kashmir, and it hosts several brooks, freshwater streams, forests, lush green mountains, and a river. Here, you see cataracts falling down the mountains; their milky-white waters flowing over the roads and splashing against the rocks, before commingling with the muddy waters of River Neelum.

Athmuqam is the capital city of Neelum Valley. It has been administratively divided into two sub-districts: Athmuqam and Sharda. From Muzaffarabad, a tarred road comfortably leads you to Sharda, whence you need to travel on a rocky and curvy jeep track, which can take you to the farthest town of the region, Tau Butt.

Before Partition, this region was known as Drawah. The Azaad Kashmir government, in 1956, the ninth year of its rule, held a cabinet meeting to rechristen the River Kishanganga as the River Neelum, and the Drawah region as Neelum Valley.

The new names were proposed to the cabinet by war hero, Syed Mohammad Amin. The cabinet approved them, and thus, Drawah of the yore is now Neelum Valley of Azaad Kashmir.

When the far-flung Kashmiri villages located at the feet of the Himalayas beckoned me, I bade adieu to my job and my city before packing up for Kashmir, where lush green mountains were ready to take me in.

After we arrived in Jhelum district, I stopped on the bridge to look down into the River Jhelum. The muddy water flowed down slowly. I was going to meet the same river upstream, where it enters into Pakistan from Azaad Kashmir (and changes its name from Neelum to Jhelum). The river seemed too sluggish in the plains of the Punjab, but I knew that up in the mountains, it is furious and noisy, with green waters winding through narrow mountain passes.

Cities, town and villages went by one after the other; Rawalpindi was gone; then from Murree, the car darted towards Muzaffarabad. The road from Kohala to Muzaffarabad was narrow but tree-lined; the car travelled under the shadows of the trees. The surrounding mountains had worn the newly-sprouted bright-coloured grass.

There was greenery everywhere, punctuated with pomegranate trees that lined up the road and proudly held out their red petals. Against their green backdrop, the red petals seemed almost seductive. I thought of stealing them from the pomegranate trees, but the very next moment, Jon Elia intruded my subconscious, saying, “dekh lo phool, phool torro mat” (Look at the flowers, don’t snip off the flowers).

The pomegranate petals continued to dance along the road until we reached Muzaffarabad – a densely populated city, with houses literally sitting on the roofs of other houses.

After crossing over the River Neelum Bridge, I had to leave the car and hire a jeep, which was to take me to my destination, the Neelum Valley.

As I was being driven along the River Neelum, I was amused to notice how contentedly this river flowed, serving as natural border between Pakistan and India, oblivious to their animosity.

Pakistan is building the Neelum-Jhelum hydropower dam on the River Neelum. It was summertime, but the project still appeared to be frozen. The jeep entered Athmuqam and moved through its crowded streets before emerging on the other side that faced Keran. At the other end of the bridge that spanned over the River Neelum, was Indian-held Kashmir.

Travelling along the Line of Control, I felt that although the two Kashmirs had been divided by a border, they held many things in common: on the both sides of this divide, jeeps and buses play the same music; culture and cuisine is the same; the population on both sides belongs to the same ethnicity, draws water from the same river, and lives under the same clouds; the difference is seen only on the masts that hoists the national flags – the flags are different, so are the governments and perhaps the hearts, too.

The driver notched up the music volume and the song that rolled off

We arrived in the village of Dowarian. From this point on, a trail leads to the Ratti Gali Lake. Nature probably worked long and hard to create Ratti Gali, first carpeting it with green velvet grass, and then speckling it with yellow, blue, and orange shades.

The blue waters and scenic beauty of this lake gravitate tourists with such a pull that they would battle mountains, rivers, and the hardships of trekking to arrive at this spot. A sight of Ratti Gali Lake is worth all the trouble.

The jeep continued to move along. At a little distance from the turn to Ratti Gali, a road branches out and treks up the mountain to meet the village of Upper Neelum. Perhaps, the entire valley takes its name from this village.

The jeep arrived in Sharda and stopped at its main marketplace. My eyes strayed to a few donkeys standing on the rooftops of houses and shops and grazing wild grass that had sprung up there. Seeing donkeys on rooftops particularly struck me as quite hilarious.

In Sharda, houses are built on the steep mountain slopes in a way that their roofs are partly stuck into the mountain. It allows animals to easily walk onto the rooftops. The donkeys were perhaps attracted by the sweet smell of the grass here.

Sharda is one of the two sub-division of the Neelum Valley. In ancient times, it was a seat of knowledge and wisdom. If you cross over the river bridge, you would arrive at the ruins of a site that looks like a fort but which in fact used to be an academy. It falls somewhere between a city and a village, as the basic necessities of life are available in abundance at the local stores. But after leaving Sharda, it is just villages. The road turns rough, too. River Neelum fattens up here.

Some historians believe that Sharda was the name of a Hindu temple. Research is wanting on whether Sharda was a temple or an academy. Findings by one of the Azaad Kashmir’s renowned researchers Dr Ahmed Deen Sabir suggest that Sharda and Saraswati are two wives to Brahma, the Hindu god of creation (in Hindu mythology, they are the goddesses of knowledge and wisdom). In the ancient age, temples would serve not only as places of worship and meditation but also as centres of education. Al-Beruni describes the geography and conditions of this temple:

“After Multan’s Sun Temple, Chakraswami temple of Thanesar, and the Somnath Temple, Sharda, too, is a big temple. It is a famous house of idols located at a distance of two or three days towards Kohistan-e-Balour from Srinagar.”

In the 21st century, the town of Sharda, overlooking the River Neelum, is known only as a tourist attraction. The River Neelum flows downhill, quietly touching its feet.

We resumed our journey. The tarred road came to an end, and the rocky dirt track began. Several brooks intersected our path. The jeep would slow down to cross through the water and then resume its bumpy journey.

Sitting inside, I felt as if I were riding on camel-back. The sunlight was hurrying up to escape from the mountain. The chir pine trees grew their shadows long. When the jeep arrived at Kail, a earth-scented breeze rushed to welcome me; it dallied everywhere.

After checking into the tourism department motel, I chose to sit in the balcony of my room to watch the hustle and bustle of the valley as the sun set. To my right, on a rooftop two kids were playing tennis with a green plastic ball. On another rooftop, just next to them, four boys were playing another game, perhaps Stapoo or a variation of it.

Far below in the valley, on a slope that had been girdled by wood logs, some women trod a wet dirt trail, carrying on their heads pitchers made of bronze and copper and filled with water. At the starting end of the trail flowed a clean brook; a fallen tree trunk forming an arch over it. On the banks of the brook and over the tree trunk sat a few other women doing laundry. The women who carried water on their head had filled the pitchers from this same brook, walking home in pairs.

Next to this lavoir was a field enclosed with wooden planks. Two young girls were playing in the field, they would whirl round and round, and shortly after, fall down in the unsown furrows, their heads spinning. They would keep giggling for several minutes. I could hear the sound of their giggles, coupled with the laughter of the tennis-playing kids. The girls would then get up again, spin round and round and collapse; the game continued for several rounds.

Just below my balcony, in a field, a large number of dandelions had blossomed. A brown cat pawed through them, sniffing. The rays from the setting sun had fired up the edges of the dandelions. To my right, smoke rose from the chimneys of the houses. The roof-slopes were painted red, white and orange. Sometimes, a jeep or a motorcycle would stir the rocky jeep track, which otherwise lay still and silent.

A little later, the last rays from the declining sun began to redden the puffed faces of the two clouds that had stubbornly stayed in the sky. As the red colour took over the sky, the chill in the air grew stronger. Before the red sky turned black, the lavoir had been emptied of its occupants, the children had ended their games, and the brown cat too, had returned home.

Now, the chimneys were emitting more smoke; dinner was being cooked. The weather suddenly grew colder and darkness engulfed everything. Dozens of lights begin to glitter in the valley. I, who had grown all weak-kneed from this beauty, was barely able to gather myself to go back into my room.

At daybreak next morning, I departed from Kail. The jeep continued its bumpy journey, somehow negotiating the wavy track in this difficult terrain. We registered at several military checkpoints along the way.

For a portion of my journey, the track ran parallel to River Neelum, almost touching it. The jeep was running on the track just one foot higher than the river. Then, we came across a cataract washing the road with its water, and spewing a lot of mud. As the jeep passed before the waterfall, a sprinkle of cold water washed over my face.

The road running along the River Neelum began to gain altitude again, and I felt the jeep almost taking off. The river had been left below in the mountains. Next, we were to pass by the villages of Sardari, Phalwai and Hilmet, before arriving in Tau Butt, where the jeep was to end its journey.

That day, after leaving Kail, I noticed that women in this region were very industrious. They worked hard in the fields and took vigilant care of the cattle. I also noticed that almost all of the women wore red; perhaps they favoured this colour. Eight out of the 10 women there wore red dresses.

We passed by several groups of Bakarwal nomads that travelled along the road with their flocks of sheep and goats. The animals would readily give way to the jeep as soon as they heard the engine. The Bakarwal tribes are known for taking regular long journeys from Kashmir to the Deosai plain, passing through the highest mountain passes of the Himalayas. After arriving in the Deosai plain, some of their groups would journey to Skardu and others would travel to Astore.

Since snow at the Deosai plain had not thawed yet, the Bakarwals were moving at a very slow pace, camping with frequent intervals. Making a stay near every village that they came across.

Nomadic life is quite strange. Nomads bury their dead wherever they die. Their graves can be found scattered from Kashmir to Skardu and Astore. One of the nomads told me that for centuries, their generations had lived the same life. Their elders had trodden the same path. The nomads had spent entire eras existing in unending journeys .

I saw a Bakarwal slaughtering his goat near the riverbank. The sight stunned me. I knew that Bakarwals would never slaughter their animal even if they were dying with starvation. What had led this man to kill his goat?

On inquiring, I learned that the goat had fallen off a mountain and broken both of its hind legs. The nomads carried it in their arms for one day, but it was not possible for them to continue to do so. It reminded me of Mushtaq Ahmed Yusufi who says, “In the entire Islamic World, I have not seen a single goat die of natural causes.”

The journey continued. The track crossed through streams that flowed over it. The jeep marched on. Hearing the sound of the jeep-horn, a nomad girl turned around with a start, and quickly hid her face in her palms. Behind the fingers her green eyes dilated. She was carrying a tea kettle and a transparent plastic bag, in which, two tea cups and a few dry rottis (flatbread) were visible.

I wished I could tell her, ‘If you are a nomad, I, too, am a homeless person at this hour. If both of us are humans, why should one hide from the other?’ The jeep moved on, leaving the gypsy girl far behind. In my rear view mirror, she stood still.

There was a time when I had given thought to the idea of travelling across Kashmir with these nomads to arrive at the Deosai plain, and then journey on to Skardu, enjoying the hospitality of the Bakarwals gypsies, sipping tea from steaming cups. Who knows, one day maybe this dream will come true.

We arrived in Jaam Garh, the town of refugees. When Hindu-Muslim violence had escalated in Indian-held Kashmir, the entire population of a village situated along the Line of Control, left their homes and, crossing over the river under the cover of night, migrated to Azaad Kashmir. These refugees have been accommodated in Jaam Garh by the state government.

The entire village has painted its rooftops with a single colour: orange. Every house has a tale of suffering, every person remembers someone they left behind and everyone mourns their burnt down houses. The jeep passed through the town silently; there was silence everywhere, as if the people were mute or had lost their voices permanently.

After a four-hour bumpy drive from Kail, we finally entered Tau Butt. It is an isolated, mountainous village with wood-framed houses, specifically designed for this region. The fields were enclosed by barbed wires, perhaps, for demarcation. The River Neelum flowed fast and furiously in the middle of the valley. Farmers were tilling their fields for the next crop.

A few young children looked out from the windows of the houses and waved at me. Some old men were seen gathered outside small shops. Red scarves fluttered in the fields. I was to spend the night in this village.

The next morning, soon after leaving my bed, I started walking towards the last human habitation of Kashmir. It is a village named Gagai, and you can get to this place only by travelling on foot. I went through a series of fields and jungles, meeting birds and animals, including one or two marmots.

The Gagai rivulet was running along me, furious and foamy. Soon I found myself in a clearing at the foot of the mountains, where the Gujjar rivulet flowing down from the Barzal Pass meets the Gagai rivulet, forming a single stream that would end up in the River Neelum at Tau Butt.

The sun began to shine brightly. A wild squirrel descended from a tree top, only to climb up a wood log where it then enjoyed a sunbath. The air was still chilly. I could hear shrilling marmots, which must be nearby. Before arriving at my destination, I had to pass through yet another jungle.

No Achievement 1 & Plagarized Content

@yasirali281, first of all, you haven't made your achievement 1 until now to get verified.

Secondly, you are posting plagiarized content continuously. All the content in your all posts is from the internet. I just checked it out on your profile.

These are the sources of this content:

@endingplagiarism

@jawad101

Downvoting a post can decrease pending rewards and make it less visible. Common reasons:

Submit

This content appears to be plagiarised as indicated by @aniqamashkoor.

If you have not already done so, you should head to the newcomers community and complete the newcomer achievement programme. Not only will you earn money through upvotes, you will learn about content etiquette;

You are currently in Stage 1 of our 4 Stage Process:

👉 Stage 1 - 1st Warning - Pointing offenders towards Achievement 3 and highlighting this process. All plagiarised posts currently pending rewards will be flagged and downvoted to $0 rewards.

Stage 2 - A Final Warning - Another request to stop and that plagiarism will not be tolerated. Downvotes amounting to 20% of total pending rewards according to steemworld.

Stage 3 - A stronger message - Downvotes amounting to 50% of pending rewards.

Stage 4 - The strongest message possible - Downvotes amounting to 100% of pending rewards.

Plagiarists will bypass stage 1 if translated from another language.

Notification to community administrators and moderators:

@toufiq777 ADMIN Curator+CR Bangladesh

@nahidhasan23 MOD Verified+Delegation [2000sp]

@sohanurrahman MOD Verified+Delegator [650SP]

@steem-bangladesh MOD Community Blog Account

Downvoting a post can decrease pending rewards and make it less visible. Common reasons:

Submit

Thanks for letting us no. He is now muted.

Downvoting a post can decrease pending rewards and make it less visible. Common reasons:

Submit