8 GREAT WOMEN TO COMMEMORATE ON MARCH 8: Marie Curie

8 GREAT WOMEN TO COMMEMORATE ON MARCH 8: Marie Curie

Hello Steemians! How are you?

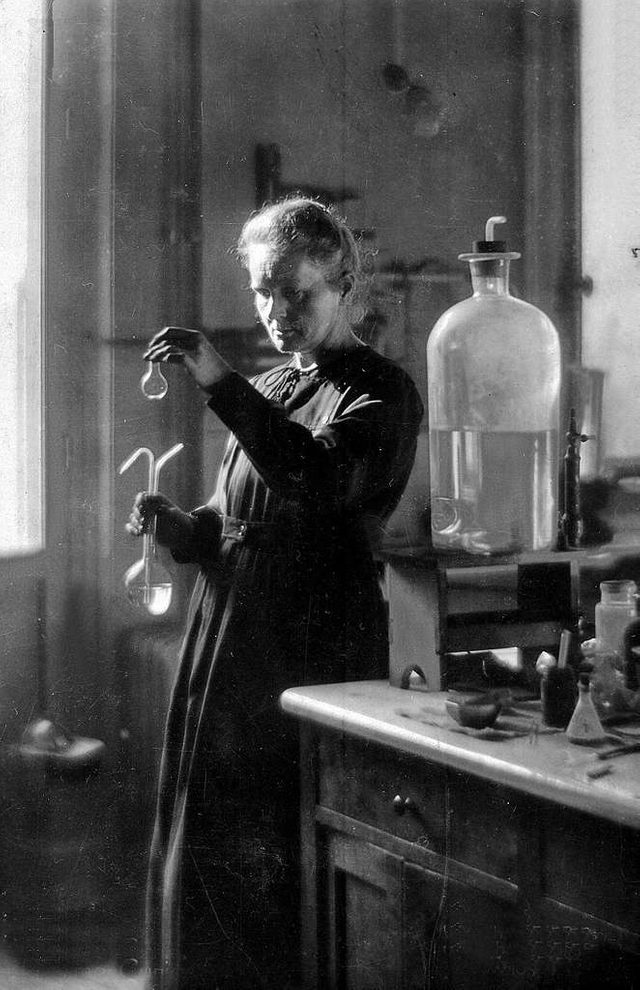

In this third day I am going to tell you about the most famous scientist in history, a woman who dedicated her life to science and whose research led her to receive two Nobel Prizes: Marie Curie.

Marie Curie (1867-1934)

Maria Salomea Skłodowska-Curie was born in Warsaw, in what was then the Tsardom of Poland (territory administered by the Russian Empire). Daughter of a professor of Physics and Mathematics and a teacher, pianist and singer, the first years of her life were marked by the death of her mother and sister.

She studied clandestinely at the "floating university" in Warsaw and began her scientific training. The floating (or flying) university was a clandestine institution, open to women, and which offered young Poles a quality education in their own language. The name comes precisely from the need they had to constantly change location to escape Russian control.

With her sister Bronisława they made a "ladies' pact", in which they agreed to pay for each other's studies. Maria worked as a governess in Warsaw, while helping pay for her sister's studies of Medicine in Paris. In 1891, it was Maria's turn (from now on Marie, as she was called in France), who enrolled at the Université de Paris, studying Physics, Chemistry and Mathematics.

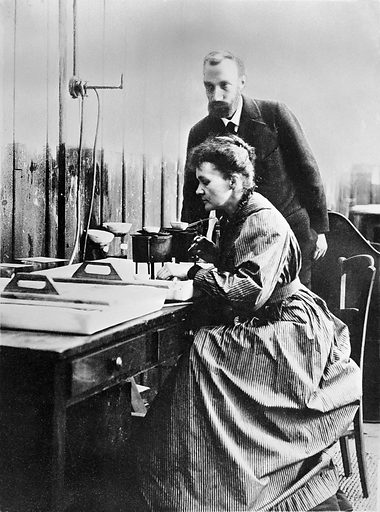

She studied during the day and taught at night. In 1893 she graduated in Physics and in 1894, with the help of a scholarship, she graduated in Mathematics. In 1894, she met Pierre Curie. Their interest in science brought them together, initially developing a strong friendship in the laboratory, until he proposed to her. At first Marie did not accept, as she planned to return to live in Poland and Pierre declared that he was willing to go with her, even if it meant pursuing another career. They married in July 1895, in a simple wedding without a religious ceremony.

The following year, encouraged by her husband, Marie decided to write her doctoral thesis on the work of Henri Becquerel, a French physicist who had accidentally discovered radioactivity while researching fluorescence. In June 1903, Marie Curie defended her doctoral thesis Recherches sur les substances radioactives (Research on radioactive substances) at the Faculty of Sciences of the Sorbonne Université (Sorbonne University) for which she obtained her doctorate in Physical Sciences.

From 1897, as they did not have their own laboratory, the couple began their studies in a shed next to the School of Physics and Chemistry, with subsidies from metallurgical and mining companies and some foreign organizations and governments. They were not aware of the harmful effects to which they were exposed by the continuous work with radiation and with substances without protection (at that time, diseases had not been associated with radiation).

In July 1898, they published a joint article in which they announced that they had succeeded in isolating an element that they called "polonium", in honor of Marie's country of origin, and in December 1898, they announced the existence of a second element, which they called "radium", derived from a Latin word meaning ray. In 1900, Marie Curie was the first woman to be appointed professor at the Ecole Normale Supérieure, while her husband received a chair at the University of Paris. Although they did not receive it in person, in 1903, the Curies were awarded the Nobel Prize in Physics, thus making Marie the first woman to receive this award.

By then, the couple was already suffering from fatigue and inflammation, the first health problems resulting from their continuous exposure to radioactivity. But it was in 1906, when Pierre died as a result of a skull fracture after falling under the wheels of a horse-drawn carriage. During the following years, Marie would suffer from depressive episodes, although she found support in her family, and continued with her research work.

In 1906, the Physics Department of the University of Paris offered her her husband's position and she was the first woman to hold a position as a professor at that university and the first director of a laboratory at that institution. Between 1906 and 1934, the university admitted 45 women without gender restriction, as had happened before.

Curie was already a member of the Swedish, Czech and Polish Academy of Sciences, the American Philosophical Society and the Imperial Academy of St. Petersburg and an honorary member of many other scientific associations. Despite all these achievements, the public attitude towards her tended to be xenophobic. In 1911, Marie was awarded the Nobel Prize in Chemistry for her demonstration of the isolation of radium, becoming the first person to win two Nobel Prizes. The French press barely covered the event.

Her research helped to better understand the effects of radiation and its use in medical diagnosis and treatment. When World War I broke out, she became the director of the Radiology Service of the French Red Cross and directed the installation of mobile X-ray units. She trained other women as assistants and was one of the first women to obtain a driver's license after applying for it to personally operate the mobile X-ray units.

In 1934, Marie died of aplastic anemia – a rare disorder in which the spinal cord does not produce enough blood cells – probably contracted from the radiation she was exposed to in her work.

To achieve her scientific achievements, Marie Curie had to overcome the obstacles she encountered as a woman, both in her native country and in her new homeland. Her work, alone and together with her husband, contributed substantially to the global development of the 20th and 21st centuries. Marie insisted that the monetary donations and prizes awarded to her should be given to scientific institutions and research. She also did not patent the process of isolating radium, but left it open to research by the entire scientific community. She was a pioneer of gender equality in science and supported scientific education for women.

I hope you enjoyed today's story, I'd love to read your comments. Thank you all!

8 GRANDES MUJERES PARA CONMEMORAR EL 8 DE MARZO: Marie Curie

8 GRANDES MUJERES PARA CONMEMORAR EL 8 DE MARZO: Marie Curie

¡Hola steemians! ¿Cómo están?

En esta tercera entrega les voy a contar sobre la científica más famosa de la historia, una mujer que dedicó su vida a la ciencia y cuyas investigaciones la llevaron a recibir dos premios Nobel: Marie Curie.

Marie Curie (1867-1934)

Maria Salomea Skłodowska-Curie nació en Varsovia, en lo que entonces era el Zarato de Polonia (territorio administrado por el Imperio ruso). Hija de un profesor de

Física y Matemáticas y una maestra, pianista y cantante, los primeros años de su vida estuvieron marcados por la muerte de su madre y de su hermana.

Estudió clandestinamente en la "universidad flotante" de Varsovia y comenzó su formación científica. Las universidad flotante (o volante) era una institución

clandestina, abierta a las mujeres, y que ofrecía a los jóvenes polacos una educación de calidad en su propio idioma. El nombre viene precisamente de la

necesidad que tenían de cambiar constantemente de ubicación para escapar del control ruso.

Con su hermana Bronisława hicieron un "pacto de damas", con el que se comprometieron a pagarse mutuamente los estudios. Maria trabajó como institutriz en Varsovia, mientras ayudaba a pagar los estudios de medicina de su hermana en París. En 1891, era el turno de Maria (desde ahora Marie, como la llamaron en Francia), quien se matriculó en la Université de Paris, en las carreras de Física, Química y Matemáticas.

Estudiaba durante el día y daba clases por la noche. En 1893 se licenció en Física y en 1894, con la ayuda de una beca, se licenció en matemáticas. En 1894, conoció a Pierre Curie. El interés que ambos tenían por la ciencia los unió, al principio desarrollando una fuerte amistad en el laboratorio, hasta que él le propuso matrimonio. Al principio Marie no aceptó, ya que en sus planes estaba volver a vivir a Polonia y Pierre declaró que estaba dispuesto a ir con ella, aunque eso significara dedicarse a otra carrera. Contrajeron matrimonio en julio de 1895, en una boda sencilla y sin ceremonia religiosa.

El siguiente año, animada por su marido, Marie decidió hacer su tesis doctoral acerca de los trabajos de Henri Becquerel, un físico francés que había descubierto accidentalmente la radiactividad mientras investigaba sobre la fluorescencia. En junio de 1903, Marie Curie defendió su tesis doctoral Recherches sur les substances radioactives (Investigaciones sobre las sustancias radiactivas) en la facultad de Ciencias de la Sorbonne Université (Universidad de La Sorbona) por la que obtuvo su doctorado en Ciencias Físicas.

A partir de 1897, como no tenían laboratorio propio, la pareja empezó sus estudios en un cobertizo junto a la Escuela de Física y Química, con subsidios de empresas metalúrgicas y mineras y algunas organizaciones y gobiernos extranjeros. No eran conscientes de los efectos nocivos a los que se veían expuestos con el continuo trabajo con la radiación y con sustancias sin protección (en esa época no se habían asociado las enfermedades a la radiación).

En julio de 1898, publicaron un artículo conjunto en el que anunciaban haber logrado aislar un elemento al que llamaron "polonio", en honor al país de origen de Marie, y en diciembre de 1898, anunciaron la existencia de un segundo elemento, al que llamaron "radio", derivado de un vocablo latino que significa rayo. En 1900, Marie Curie fue la primera mujer en ser nombrada catedrática de la Ecole Normale Supérieure mientras su marido recibió una cátedra de la Universidad de París. Aunque no lo recibieron en persona, en 1903, los Curie fueron galardonados con el Premio Nobel de Física, convirtiéndose así Marie en la primera mujer en recibir dicho galardón.

Ya para ese entonces, el matrimonio padecía de fatiga e inflamaciones, los primeros problemas de salud producto de su exposición contínua a la radioactividad. Pero fue en 1906, cuando Pierre murió a consecuencia de una fractura en el cráneo al caer bajo las ruedas de un carruaje tirado por caballos. Durante los años siguientes, Marie sufriría episodios depresivos, aunque encontró apoyo en su familia, y continuó con los trabajos de investigación.

En 1906, el Departamento de Física de la Universidad de París le ofreció el puesto de su esposo y fue la primera mujer en ocupar un cargo como profesora en dicha universidad y la primera directora de un laboratorio en esa institución. Entre 1906 y 1934, la universidad admitió a 45 mujeres sin restricción de género, como antes sucedía.

Curie ya era miembro de la Academia de Ciencias de Suecia, de la República Checa y de Polonia, la Sociedad Filosófica Estadounidense y la Academia Imperial de San Petersburgo y miembro honorario de muchas otras asociaciones científicas. A pesar de todos estos logros, la actitud del público hacia ella tendía a la xenofobia. En 1911, Marie recibió el Premio Nobel de Química por su demostración del aislamiento del radio, convirtiéndose en la primera persona en ganar dos premios Nobel. La prensa francesa apenas cubrió el evento.

Sus investigaciones ayudaron a comprender mejor los efectos de la radiación y su uso en el diagnóstico y tratamiento médico. Cuando estalló la Primera Guerra Mundial se convirtió en la directora del Servicio de Radiología de la Cruz Roja francesa y dirigió la instalación de unidades móviles de radiografía. Instruyó a otras mujeres como ayudantes y fue una de las primeras mujeres en obtener licencia de conducir luego de solicitarla para manejar personalmente las unidades móviles de rayos X.

En 1934, Marie falleció a causa de una anemia aplásica – un trastorno raro en el que la médula espinal no produce suficientes glóbulos –, probablemente contraída por las radiaciones a las que estuvo expuesta en sus trabajos.

Para alcanzar sus logros científicos, Marie Curie tuvo que superar los obstáculos que encontró en su camino por ser mujer, tanto en su país natal como en su nueva patria. Su obra, en solitario y junto a su marido, contribuyó sustancialmente al desarrollo mundial de los siglos XX y XXI. Marie insistía en que las donaciones monetarias y premios que le otorgaban, debían entregarse a las instituciones científicas y a las investigaciones. Tampoco patentó el proceso de aislamiento del radio, sino que lo dejó abierto a la investigación de toda la comunidad científica. Fue una precursora de la igualdad de género en la ciencia y apoyó la educación científica de las mujeres.

Espero que hayan disfrutado de la historia de hoy, me gustaría leer sus comentarios. Muchas gracias a todos.

chica Polaca! <3

Downvoting a post can decrease pending rewards and make it less visible. Common reasons:

Submit