8 GREAT WOMEN TO COMMEMORATE ON MARCH 8: Rose O'Neill

8 GREAT WOMEN TO COMMEMORATE ON MARCH 8: Rose O'Neill

Hello Steemians!

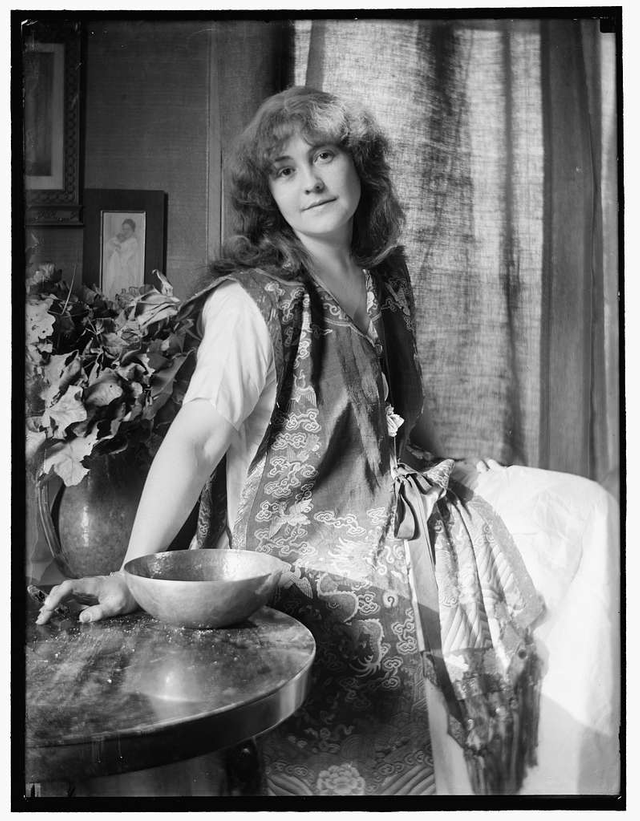

Today I bring you the story of a great illustrator, a committed suffragette and an unconventional woman who lived her own life and claimed the right to vote for women with her drawings.

Rose O'Neill (1874– 1944)

Born in Wilkes-Barre, Pennsylvania, she was one of seven children of a bookseller and a homemaker. She was raised in rural Nebraska, and from an early age she showed an interest in the arts, primarily drawing, painting, and sculpture. At age 13 she won first prize in a children's drawing contest held by a local newspaper, and with the help of the contest judges, she began illustrating for various newspapers.

Soon her father took her to New York, stopping in Chicago to visit the World's Fair, where Rose had her first exposure to great paintings and sculpture. Once in New York, Rose was placed in a boarding school run by French nuns, who accompanied her to publishers and magazines to display her work. Rose sold over 60 of her illustrations and was commissioned to do more. Before long she became a popular illustrator, and by the age of 25 she was working for women's magazines such as Life, Ladies' Home Journal, and Harper's Monthly, and was being paid very good for her work. In 1896 she began publishing her strip "The Old Subscriber" in Truth magazine, making her the first female cartoonist in the United States. In 1897, at the age of 23, O'Neill became the only woman on the staff of the humor magazine Puck, where she produced over 700 illustrations.

In 1896 she married Gray Latham, but this marriage did not last long because he spent a good part of Rose's fortune on gambling and other women. In 1902 she married Harry Leon Wilson, the literary editor of Puck who wrote her anonymous love letters. During their years together Harry wrote books that O'Neill illustrated, including one of them, Ruggles of Red Gap, which was adapted several times for film. They divorced in 1907.

After her second divorce, she moved into the family home, a huge mansion in the Ozark Mountains, which she had helped finance and called Bonniebrok, and which even served as inspiration for her novels and comics. It was there that she invented her favorite characters, the ones that made her famous: the Kewpies, a kind of mischievous and affectionate cupid babies whose only idea, according to the author herself, is to teach people to be happy and kind. The first Kewpie strip was published in December 1909, in Ladies' Home Journal magazine. Kewpie is a variant of Cupid, the Roman god of love.

Thanks to the success of the Kewpie doll in the early 20th century, O'Neill became one of the highest-paid artists of the era, with the characters appearing in numerous illustrations, advertisements and products such as paper dolls. In 1912, a German porcelain manufacturer began making Kewpie dolls, and that same year O'Neill traveled to Germany to oversee production.

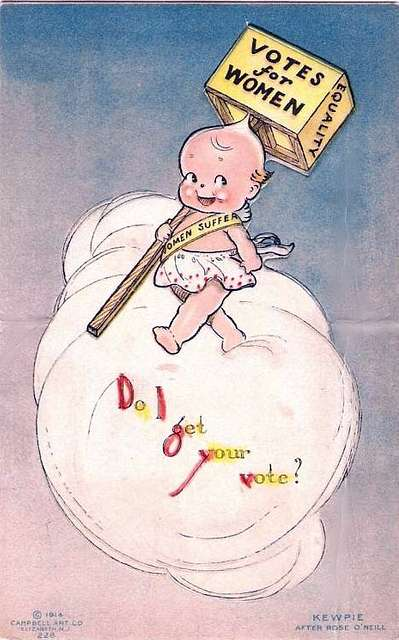

A postcard with a Kewpie promoting Votes for Women Source

Together with her sister Callista, she joined the suffragette movement, becoming an active advocate for women's rights. She drew dozens of posters, postcards and political cartoons for the cause. She even pushed for a change in women's dress, getting rid of the corset and wearing loose clothing.

The success of the Kewpies allowed her to accumulate a considerable fortune. Nevertheless, O'Neill continued to work on her own art. As a sculptor and painter, she exhibited her works in New York and, convinced by her sculpture teacher Auguste Rodin, also in Paris. As a novelist and poet, she published eight novels and many children's books. In her apartment in Washington Square Park, she held meetings attended by poets, actors, dancers and great thinkers of her time, for which she was called the "Queen of Bohemian Society."

Although she never stopped working, Rose was generous and did not like to save. She bought several properties, supported her family in Missouri and played the role of patron to several artist friends, and by this time photography began to replace illustrations as a commercial vehicle. By the 1940s she was broke, so she took refuge again in Bonniebrook where she continued to draw, participate in women's workshops and donate her time and art to the School of the Ozarks. In 1944, she died at the age of 69 and her house was converted into a museum.

Rose Cecil O'Neill was an iconoclast in every sense of the word. A self-taught bohemian artist, she made her way in a male-dominated sphere to become the first woman to turn her work into a merchandising empire, creating an icon of American popular culture. At a very young age, she redefined what a female artist could achieve creatively and commercially in the late 19th century.

Thank you very much for reading, and as always, I look forward to your comments.

8 GRANDES MUJERES PARA CONMEMORAR EL 8 DE MARZO: Rose O'Neill

8 GRANDES MUJERES PARA CONMEMORAR EL 8 DE MARZO: Rose O'Neill

Hoy les traigo la historia de quien fue una gran ilustradora, una comprometida sufragista y una mujer poco convencional que vivió a su manera y reivindicó con sus dibujos el derecho al voto para las mujeres.

Rose O'Neill (1874– 1944)

Nació en Wilkes-Barre, Pensilvania, y era una de los siete hijos de un vendedor de libros y una ama de casa. Fue criada en una zona rural de Nebraska, y desde pequeña demostró interes por las artes, principalmente el dibujo, la pintura y la escultura. A los 13 años obtuvo el primer premio de un concurso de dibujos para niños organizado por un periódico local, y con ayuda de los jueces del concurso, empezó a ilustrar para varios periódicos.

Pronto su padre la llevó a New York, parando en Chicago para visitar la Feria Mundial, donde Rose tuvo su primer contacto con grandes pinturas y esculturas. Una vez en New York, Rose quedó en un internado de monjas francesas, que la acompañaron a visitar editoriales y revistas para mostrar su trabajo. Rose vendió las más de 60 ilustraciones y tuvo pedidos de que realizara más. En muy poco tiempo se volvió una ilustradora popular y con menos de 25 años trabajaba para revistas femeninas como Life, Ladies' Home Journal y Harper's Monthly y recibía muy buen pago por su trabajo. En 1896 empezó a publicar su tira "The Old Subscriber" en la revista Truth, lo que la convirtió en la primera mujer historietista de los Estados Unidos. En 1897, a los 23 años, O'Neill se convirtió en la única mujer en el equipo de la revista humorística Puck, donde realizó más de 700 ilustraciones.

En 1896 se casó con Gray Latham, pero este matrimonio no duró mucho tiempo debido a que se gastó una buena parte de la fortuna que ganaba Rose en el juego y en otras mujeres. En 1902 se casó con Harry Leon Wilson, el editor literario de Puck que le escribía cartas anónimas de amor. Durante los años que estuvieron juntos Harry escribía libros que O'Neill ilustraba, incluso uno de ellos, Ruggles of Red Gap, fue adaptada varias veces al cine. Se divorciaron en 1907.

Luego de su segundo divorcio, se trasladó a la casa familiar, una enorme mansión en las montañas de Ozark, que ella misma había ayudado a financiar y llamó Bonniebrok y que incluso le sirvió como inspiración para sus novelas e historietas. Allí fue donde inventó a sus personajes fetiches, los que la hicieron reconocida: los Kewpies, una especie de bebés cupidos, traviesos y cariñosos cuya única idea, según la propia autora, es enseñar a la gente a ser alegre y amable. La primera tira de Kewpie fue publicada en diciembre de 1909, en la revista Ladies' Home Journal. Kewpie es una variante de Cupido, el dios romano del amor.

Gracias al éxito del Kewpie a comienzos del siglo XX, O'Neill llegó a ser una de las artistas mejores pagadas de la época, protagonizando éste personajes numerosas ilustraciones, publicidades y productos como muñecas recortables. En 1912, un fabricante alemán de porcelana comenzó a hacer muñecas Kewpie, y ese mismo año O'Neill viajó a Alemania para supervisar la producción.

Una postal con un Kewpie promoviendo el voto femenino Source

Junto a su hermana Callista, se unió al movimiento sufragista, volviéndose una activa defensora de los derechos de las mujeres. Dibujó decenas de carteles, postales y caricaturas políticas para la causa. Incluso impulsó un cambio en la vestimenta femenina, deshaciéndose del corset y usando ropa holgada.

El éxito de los Kewpies le permitió acumular una importante fortuna. Aun así, O'Neill continuó trabajando en su propio arte. Como escultura y pintora, exhibió sus trabajos en New York y, convencida por su maestro de escultura Auguste Rodin, también en Paris. Como novelista y poeta, publicó ocho novelas y muchos libros para niños. En su departamento de Washington Square Park, celebraba reuniones donde asistían poetas, actores, bailarines y grandes pensadores de su época, por lo que la llamaron la "Reina de la Sociedad Bohemia".

A pesar de que no dejó de trabajar, Rose era generosa y no le gustaba ahorrar. Se compró varias propiedades, matenía a su familia en Missouri y cumplió el papel de mecenas para varios amigos artistas y, para ese entonces, la fotografía comenzó a reemplazar las ilustraciones como vehículo comercial. Para los años 40, estaba en ruina, por lo que se refugió de nuevo en Bonniebrook donde siguió dibujando, participando en talleres de mujeres y donando su tiempo y artes a la Escuela de Ozarks. En 1944, falleció a la edad de 69 años y su casa fue convertida en museo.

Rose Cecil O'Neill fue una iconoclasta en todo sentido. Una artista bohemia autodidacta que supo abrirse camino en una esfera dominada por hombres, para convertirse en la primera mujer en hacer de su obra un imperio de merchandising, creando un ícono de la cultura popular americana. De muy joven redefinió lo que una mujer artista podría lograr creativa y comercialmente a finales del siglo XIX.

Muchas gracias por leer, y como siempre, espero sus comentarios.