Satoshi Nakamoto.

Who Is Satoshi Nakamoto?

Satoshi Nakamoto is the name used by the creator/s of the protocol used in the Bitcoin cryptocurrency.

Though the name Satoshi Nakamoto is nearly synonymous with Bitcoin, the physical person that the name represents has never been found, leading many people to believe that it is a pseudonym for a person with a different identity or a group of people.

Crucial

Satoshi Nakamoto may not be a real person. The name might be a pseudonym for the creator or creators of Bitcoin who wish to remain anonymous.

Understanding Satoshi Nakamoto

For most people, Satoshi Nakamoto is the most enigmatic character in cryptocurrency. To date, it is unclear if the name refers to a single person or a group of people. What is known is that Satoshi Nakamoto published a paper in 2008 that jumpstarted the development of cryptocurrency.

Understanding Satoshi Nakamoto

For most people, Satoshi Nakamoto is the most enigmatic character in cryptocurrency. To date, it is unclear if the name refers to a single person or a group of people. What is known is that Satoshi Nakamoto published a paper in 2008 that jumpstarted the development of cryptocurrency.

The paper, Bitcoin: A Peer-to-Peer Electronic Cash System, described the use of a peer-to-peer network as a solution to the problem of double-spending.1 The problem—that a digital currency or token could be duplicated in multiple transactions—is not found in physical currencies since a physical bill or coin can, by its nature, only exist in one place at a single time. Since a digital currency does not exist in physical space, using it in a transaction does not necessarily remove it from someone’s possession.

KEY TAKEAWAYS

Satoshi Nakamoto is the name on the original Bitcoin whitepaper and is the identity credited with inventing Bitcoin.It's likely that Satoshi Nakamoto is a pseudonym for a different person or persons who invented Bitcoin.

Solutions to combating the double-spend problem had historically involved the use of trusted, third-party intermediaries that would verify whether a digital currency had already been spent by its holder. In most cases, third parties, such as banks, can effectively handle transactions without adding significant risk.

History of Satoshi Nakamoto

The persona Satoshi Nakamoto was involved in the early days of bitcoin, working on the first version of the software in 2009. Communication to and from Nakamoto was conducted electronically, and the lack of personal and background details meant that it was impossible to find out the actual identity behind the name.

Nakamoto’s involvement with bitcoin ended in 2010. The last correspondence anyone had with Nakamoto was in an email to another bitcoin developer saying that they had "moved on to other things." The inability to put a face to the name has led to significant speculation as to Nakamoto’s identity, especially as cryptocurrencies increased in number, popularity, and notoriety.

While the identity of Nakamoto has not been ascribed to a provable person or persons, it is estimated that the value of bitcoins under Nakamoto's control—which is thought to be about 1 million—may exceed $5 billion in value. Given that the maximum possible number of bitcoins generated is 21 million, Nakamoto's stake of 5% of the total bitcoin holdings has considerable market power. Several people have been put forward as the "real" Satoshi Nakamoto, though none have been definitely proven to be Nakamoto.

What is blockchain?

Blockchain is a system of recording information in a way that makes it difficult or impossible to change, hack, or cheat the system.

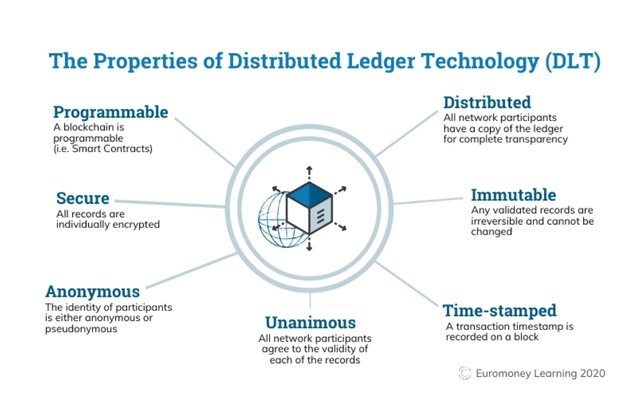

A blockchain is essentially a digital ledger of transactions that is duplicated and distributed across the entire network of computer systems on the blockchain. Each block in the chain contains a number of transactions, and every time a new transaction occurs on the blockchain, a record of that transaction is added to every participant’s ledger. The decentralised database managed by multiple participants is known as Distributed Ledger Technology (DLT).

Blockchain is a type of DLT in which transactions are recorded with an immutable cryptographic signature called a hash.

Blockchain Is Changing Finance

Our global financial system moves trillions of dollars a day and serves billions of people. But the system is rife with problems, adding cost through fees and delays, creating friction through redundant and onerous paperwork, and opening up opportunities for fraud and crime. To wit, 45% of financial intermediaries, such as payment networks, stock exchanges, and money transfer services, suffer from economic crime every year; the number is 37% for the entire economy, and only 20% and 27% for the professional services and technology sectors, respectively. It’s no small wonder that regulatory costs continue to climb and remain a top concern for bankers. This all adds cost, with consumers ultimately bearing the burden.

It begs the question: Why is our financial system so inefficient? First, because it’s antiquated, a kludge of industrial technologies and paper-based processes dressed up in a digital wrapper. Second, because it’s centralized, which makes it resistant to change and vulnerable to systems failures and attacks. Third, it’s exclusionary, denying billions of people access to basic financial tools. Bankers have largely dodged the sort of creative destruction that, while messy, is critical to economic vitality and progress. But the solution to this innovation logjam has emerged: blockchain.

Blockchain was originally developed as the technology behind cryptocurrencies like Bitcoin. A vast, globally distributed ledger running on millions of devices, it is capable of recording anything of value. Money, equities, bonds, titles, deeds, contracts, and virtually all other kinds of assets can be moved and stored securely, privately, and from peer to peer, because trust is established not by powerful intermediaries like banks and governments, but by network consensus, cryptography, collaboration, and clever code. For the first time in human history, two or more parties, be they businesses or individuals who may not even know each other, can forge agreements, make transactions, and build value without relying on intermediaries (such as banks, rating agencies, and government bodies such as the U.S. Department of State) to verify their identities, establish trust, or perform the critical business logic — contracting, clearing, settling, and record-keeping tasks that are foundational to all forms of commerce.

Given the promise and peril of such a disruptive technology, many firms in the financial industry, from banks and insurers to audit and professional service firms, are investing in blockchain solutions. What is driving this deluge of money and interest? Most firms cite opportunities to reduce friction and costs. After all, most financial intermediaries themselves rely on a dizzying, complex, and costly array of intermediaries to run their own operations. Santander, a European bank, put the potential savings at $20 billion a year. Capgemini, a consultancy, estimates that consumers could save up to $16 billion in banking and insurance fees each year through blockchain-based applications.

To be sure, blockchain may enable incumbents such as JPMorgan Chase, Citigroup, and Credit Suisse, all of which are currently investing in the technology, to do more with less, streamline their businesses, and reduce risk in the process. But while an opportunistic viewpoint is advantageous and often necessary, it is rarely sufficient. After all, how do you cut cost from a business or market whose structure has fundamentally changed? Here, blockchain is a real game changer. By reducing transaction costs among all participants in the economy, blockchain supports models of peer-to-peer mass collaboration that could make many of our existing organizational forms redundant.

For example, consider how new business ventures access growth capital. Traditionally, companies target angel investors in the early stages of a new business, and later look to venture capitalists, eventually culminating in an initial public offering (IPO) on a stock exchange. This industry supports a number of intermediaries, such as investment bankers, exchange operators, auditors, lawyers, and crowd-funding platforms (such as Kickstarter and Indiegogo). Blockchain changes the equation by enabling companies of any size to raise money in a peer-to-peer way, through global distributed share offerings. This new funding mechanism is already transforming the blockchain industry.

In 2016 blockchain companies raised $400 million from traditional venture investors and nearly $200 million through what we call initial coin offerings (ICO rather than IPO). These ICOs aren’t just new cryptocurrencies masquerading as companies. They represent content and digital rights management platforms (such as SingularDTV), distributed venture funds (such as the the DAO, for decentralized autonomous organization), and even new platforms to make investing in ICOs and managing digital assets easy (such as ICONOMI). There is already a deep pipeline of ICOs this year, such as Cosmos, a unifying technology that will connect every blockchain in the world, which is why it’s been dubbed the “internet of blockchains.” Others are sure to follow suit. In 2017 we expect that blockchain startups will raise more funds through ICO than any other means — a historic inflection point.

Incumbents are taking notice. The New York–based venture capital firm Union Square Ventures (USV) broadened its investment strategy so that it could buy ICOs directly. Menlo Park venture capital firm Andreessen Horowitz joined USV in investing in Polychain Capital, a hedge fund that only buys tokens. Blockchain Capital, one of the industry’s largest investors, recently announced that it would be raising money for its new fund by issuing tokens by ICO, a first for the industry.

And, of course, companies such as Goldman Sachs, NASDAQ, Inc., and Intercontinental Exchange, the American holding company that owns the New York Stock Exchange, which dominate the IPO and listing business, have been among the largest investors in blockchain ventures.

As with any radically new business model, ICOs have risks. There is little to no regulatory oversight. Due diligence and disclosures can be scant, and some companies that have issued ICOs have gone bust. Caveat emptor is the watchword, and many of the early backers are more punters than funders. But the genie has been unleashed from the bottle. Done right, ICOs can not only improve the efficiency of raising money, lowering the cost of capital for entrepreneurs and investors, but also democratize participation in global capital markets.

If the world of venture capital can change radically in one year, what else can we transform? Blockchain could upend a number of complex intermediate functions in the industry: identity and reputation, moving value (payments and remittances), storing value (savings), lending and borrowing (credit), trading value (marketplaces like stock exchanges), insurance and risk management, and audit and tax functions.

Is this the end of banking as we know it? That depends on how incumbents react. Blockchain is not an existential threat to those who embrace the new technology paradigm and disrupt from within. The question is, who in the financial services industry will lead the revolution?

Throughout history, leaders of old paradigms have struggled to embrace the new. Why didn’t AT&T launch Skype, or Visa create Paypal? CNN could have built Twitter, since it is all about the sound bite. GM or Hertz could have launched Uber; Marriott could have invented Airbnb. The unstoppable force of blockchain technology is barreling down on the infrastructure of modern finance. As with prior paradigm shifts, blockchain will create winners and losers. Personally, we would like the inevitable collision to transform the old money machine into a prosperity platform for all.

How Blockchain Works

Here are five basic principles underlying the technology.

- Distributed Database

Each party on a blockchain has access to the entire database and its complete history. No single party controls the data or the information. Every party can verify the records of its transaction partners directly, without an intermediary.

- Peer-to-Peer Transmission

Communication occurs directly between peers instead of through a central node. Each node stores and forwards information to all other nodes.

- Transparency with Pseudonymity

Every transaction and its associated value are visible to anyone with access to the system. Each node, or user, on a blockchain has a unique 30-plus-character alphanumeric address that identifies it. Users can choose to remain anonymous or provide proof of their identity to others. Transactions occur between blockchain addresses.

- Irreversibility of Records

Once a transaction is entered in the database and the accounts are updated, the records cannot be altered, because they’re linked to every transaction record that came before them (hence the term “chain”). Various computational algorithms and approaches are deployed to ensure that the recording on the database is permanent, chronologically ordered, and available to all others on the network.

- Computational Logic

The digital nature of the ledger means that blockchain transactions can be tied to computational logic and in essence programmed. So users can set up algorithms and rules that automatically trigger transactions between nodes.

In conclusion Satoshi Nakamoto and blockchain are changing the finance by

presenting double-edge sword for banks. On the one hand, it could potentially save banks billions in cash by dramatically reducing processing costs.

Banks are salivating at the opportunity to reduce transaction costs and the amount of paper that they process. Implementing blockchain would make banks increasingly profitable and valuable.

Santander, a bank based in Spain, put the potential savings of blockchain at $20 billion a year. Alternatively, the opportunity to start a bank with lower costs has attracted many new fintech start-ups to the market. Banks are also hedging their bets by directly investing in fintech start-ups.

Nakamoto has recommended a decentralized procedure to transactions, ultimately culminating in the creation of blockchains.

In a blockchain, timestamps for a transaction are expanded to the end of earlier timestamps established on proof-of-work, creating a historical document that cannot be changed.