Hello dear friends.

The chemical fertilizer industry has an important challenge to face, to develop materials that release nutrients in a controlled way into the soil and also avoid environmental pollution. These materials, called slow-release fertilizers, improve the utilization of nutrients by plants, since they are available for a longer period of time, which avoids losses of their components and their dispersion in the environment. That is why an international team optimized an old method to produce a solid compound that slowly releases nitrogen and calcium, two very important elements in soil fertilization.

New method, based on an old technique, to produce slow release fertilizers

emiliomoron (71)in StemSocial • 7 days ago (edited)

Hello dear friends.

The chemical fertilizer industry has an important challenge to face, to develop materials that release nutrients in a controlled way into the soil and also avoid environmental pollution. These materials, called slow-release fertilizers, improve the utilization of nutrients by plants, since they are available for a longer period of time, which avoids losses of their components and their dispersion in the environment. That is why an international team optimized an old method to produce a solid compound that slowly releases nitrogen and calcium, two very important elements in soil fertilization.

What is a Slow Release Fertilizer?

Slow-release fertilizers are those that allow the plants to have the elements that compose them in different ways, one is by delaying the availability of these elements when they are taken up by the plants, so that they can be used after they are applied, another way is to provide a mechanism that allows the availability of these nutrients for a long period of time.

Regarding the second way, prolonging the time of availability of nutrients can be achieved in different ways, some of the most studied have been by protecting the material with semi-permeable coatings, by occlusion or encapsulation in polymers, and even some chemical mechanisms such as slow hydrolysis of soluble compounds.

An advanced milling technique

Until now, to produce the common nitrogen fertilizers, Urea and ammonium nitrate, the Haber-Bosh process is used, which is a process of ammonia synthesis through the reaction of nitrogen and hydrogen, under conditions of high pressure (200 atm) and high temperature (450-500 ºC), and in the presence of a catalyst, commonly iron compounds.

But this method consumes a lot of energy, and when pure urea is used as fertilizer, its decomposition quickly releases large amounts of ammonia.

But a team of scientists at the Ruder-Boskovic Institute in Zagreb have developed an alternative and more environmentally friendly method of producing a nitrogen fertilizer, using an ancient technique, mechanochemistry, which basically involves using mechanical force to synthesize new materials and compounds.

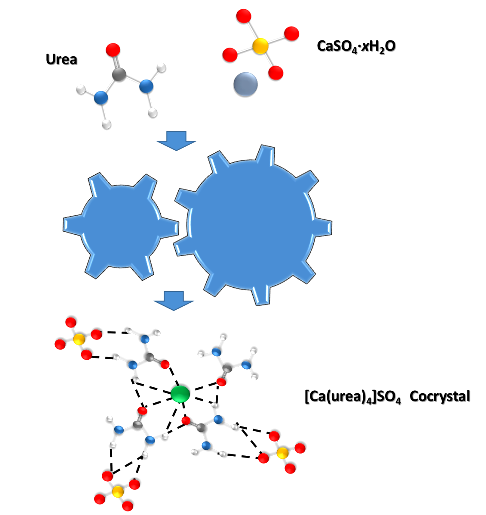

And this team of researchers relied on the grinding of two ingredients, urea and gypsum, to produce a solid compound that slowly releases nitrogen and calcium, two fundamental elements for soil fertilization, into the soil.

Specifically, the research group explored the synthesis of a calcium urea sulfate ([Ca(urea)4]SO4) cocrystal using thermally controlled mechanochemical methods, first conducting small-scale experiments in a stirring mill, monitoring the process by in situ Raman spectroscopy, and by X-ray diffraction using DESY's PETRA III X-ray source to investigate what the resulting powder consists of. The PETRA III beamline is a facility in which various types of chemical reactions can be analyzed using X-rays from a synchrotron, allowing the evolution of the mixture to be determined by applying radiation directly to the grinding vessel. The results of this research have recently been published in the journal Green Chemistry.

The grinding method made it possible to obtain a cocrystal, a solid whose crystalline structure is composed of two substances stabilized by weak intermolecular interactions that form repeating patterns. In this case, milling allowed the calcium sulfate of gypsum and urea to bind together. And according to the results, this cocrystal has a solubility in aqueous solution almost 20 times lower compared to Urea, and in addition, the reactive nitrogen emissions of this material, expressed as an amount of ammonia, were shown to be slow and progressive over 90 days, pure urea took between 1 and 2 weeks to reach the same level of emissions.

According to the researchers, pure urea forms a crystal that falls apart easily, releasing the nitrogen contained very quickly; but with calcium sulfate, through the milling process, a cocrystal is obtained that is strong enough to allow a slow release of nitrogen and calcium.

On the other hand, among the advantages of this process is that the mechanochemical process does not generate any hazardous by-products, and although the process has yet to be tested on an industrial scale and the fertilizer has yet to be tested in the field, the results are encouraging enough to continue to scale up and conduct field trials.

Hopefully, the field trials will achieve good results and a method can be obtained to reduce dependence on the traditional process, whose products release large amounts of nitrogen into the environment, while slow-release fertilizers avoid high concentrations of ions in the soil due to the rapid solubility of the product, which also reduces the impact of these products on the environment by reducing losses of ammonium ions and emissions of N2O gases into the atmosphere.