Earlier this week, WeWork, the office-share company, announced that it had lost $3.2 billion in 2020. For WeWork, that was good news: Its losses were down from $3.5 billion the previous year, when its megalomaniacal co-founder, Adam Neumann, was ousted as CEO. At his most profligate, the entrepreneur had been spending $100 million a week to attract a multibillion-dollar investment that would never come. As a newscaster intones, Neumann’s leadership took WeWork “from a $47 billion valuation to near bankruptcy in just six weeks.”

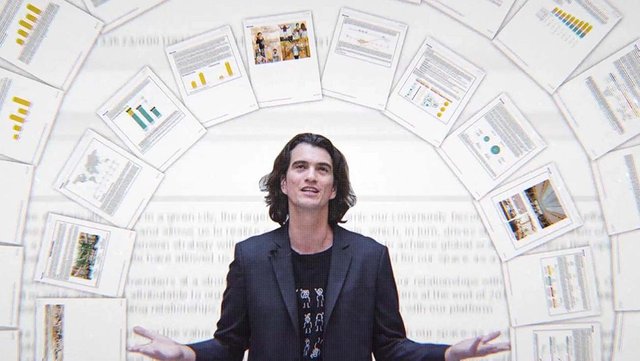

The Hulu documentary WeWork: Or the Making and Breaking of a $47 Billion Unicorn is director Jed Rothstein’s (The China Hustle) comprehensive but politically and creatively timid account of Neumann’s extravagant flameout. A SXSW selection, the film doesn’t hold back on Neumann or his delusions of grandeur. (In one excerpt from a company event, the Israel-born co-founder tells his employees that, were he to truly dedicate himself to the issue, he could solve global orphandom within two years — but I guess all those parent-less children aren’t as important as creating workplaces for freelancers who might otherwise have to suffer the crushing indignity of working at home or a café.)

Rothstein organizes his tale of WeWork’s rise and fall around Neumann’s promise of community. (Factoring heavily in the startup’s appeal, argue the doc’s journalist talking heads, is its origin story, which begins with Neumann and his co-founder Miguel McKelvey’s childhoods growing up on communes on opposite sides of the globe.) Neumann described his company as a “physical social network” and a “community that’s transparent and accountable.” That idea later extended to WeLive — an exquisitely designed dormitory mostly inhabited by single WeWork employees — and mutated into something grotesque with WeGrow, an educational institution that Neumann’s wife, Rebekah (a cousin of Gwyneth Paltrow), founded ostensibly to “elevate the world’s consciousness,” but mostly because she didn’t think any New York City private school measured up to her standards.

There’s plenty of gawking at rich people’s excesses to be had later in the doc, as the Neumanns’ narcissism is allowed to metastasize by WeWork’s outward success. In a much-reported detail back in 2019, a company financial report decreed that, in the event of Neumann’s death, his wife Rebekah — who had never worked at the company in an official capacity — would name his successor.

But the documentary is just as notable for the cultural and social analysis that it lacks as it is for its contents. There’s a conspicuous reluctance to observe the obvious elitism and extended adolescence that WeWork and WeLive cultivated, respectively — two aspects of the “coworkers as friends” paradigm that, not coincidentally, “cool” companies routinely exploit to wring more working hours from their employees. Also missing is any bewilderment at the wildly imprecise financial instruments that would deem a company almost $50 billion one day and practically nothing less than two months later. And if you’re looking for outrage that the mega-rich keep giving conmen millions (or in Neumann’s case, billions) hoping to reap hundredfold their investments instead of paying their taxes and doing their part to ensure we live in a just and equitable society, this documentary most definitely isn’t that.

There’s plenty to be angry and upset about in WeWork’s implosion, not least because, as a result of Neumann’s lies about his company’s profitability, nearly 3,000 employees lost their jobs in 2019 alone. Rothstein mostly deplores their loss of faith in Neumann’s promise of community. But because the doc makes clear from the start the hollowness of the entrepreneur’s words, it’s hard to feel too bad for, say, Neumann’s ex-assistant, who fell for a seemingly transparent ruse. If the sense of togetherness that Neumann supposedly fostered in his company culture ever existed (beyond the fratty parties and mandatory “camp” weekends that honestly sound like torturous punishments), it isn’t borne out by the illuminating interviews with former employees, whose overwhelming memories of Neumann are of his sadism and braggadocio.

Though it’s dramatically paced, WeWork also subjects viewers to repetitive montages of Neumann’s messianic messaging — the film occasionally feels as if Rothstein's trying to use up all the archival footage that he could find of his subject. Despite his New Age excesses, all those images don’t make Neumann feel special in any way, especially not after the cascade of exposés in recent years about similarly abusive leaders in any number of industries. WeWork’s numbers were exceptionally large, but so-called tech visionaries selling more than they can deliver? They’re a dime a dozen.

Venue: South by Southwest Film Festival (Section Goes Here)

Production companies: Campfire, Forbes Entertainment, Olive Hill Media

Distributor: Hulu

Director: Jed Rothstein

Producer: Ross M. Dinerstein

Executive producers: Mimi Rode, Tim Lee, Michael Cho, Kyle Kramer, Ross Girard, Danni Mynard, Rebecca Evans

Director of photography: Wolfgang Held

Editor: Samuel Nalband

Composer: Jeremy Turner

have a nice day

Downvoting a post can decrease pending rewards and make it less visible. Common reasons:

Submit