If 2018 was a year plagued by inconvenient truths, a reimagining of the art world fits squarely in line with new narratives that will continue to define the world order in 2019. As many nation-states around the world grapple with the aftermath of global moves towards conservatism, populism and justice in the digital age, their citizens are harnessing the power of technology to speak openly about issues of injustice, identity and equality that have long been percolating beneath the surface. And in the midst of this emergent culture, the art world seems — as it has been for so long — to be stubbornly disconnected from, and often out of touch with, these dialogues. Major world museums continue to perpetuate a colonialist paradigm with their frequent refusal to return artifacts that were stolen or otherwise acquired in an illegal or illegitimate fashion: during periods of occupation, colonialism and war.

Some of this reluctance stems from the fact that the problem is complex and amorphous — there's no one single solution, and there is so much history, culture and identity wrapped up in the domain of art that decision makers in the space can seem beyond reproach. It's simultaneously an intensely local and an intensely global problem — niche communities urging restitution of specific objects exist all around the world, but they don't coordinate with each other. There's also a deeper consideration: Repatriation exposes uncomfortable truths about cultural identity that most people still don't want to believe, despite progress that has been made in other aspects of public opinion.

Repatriation exposes uncomfortable truths about cultural identity that most people still don't want to believe.

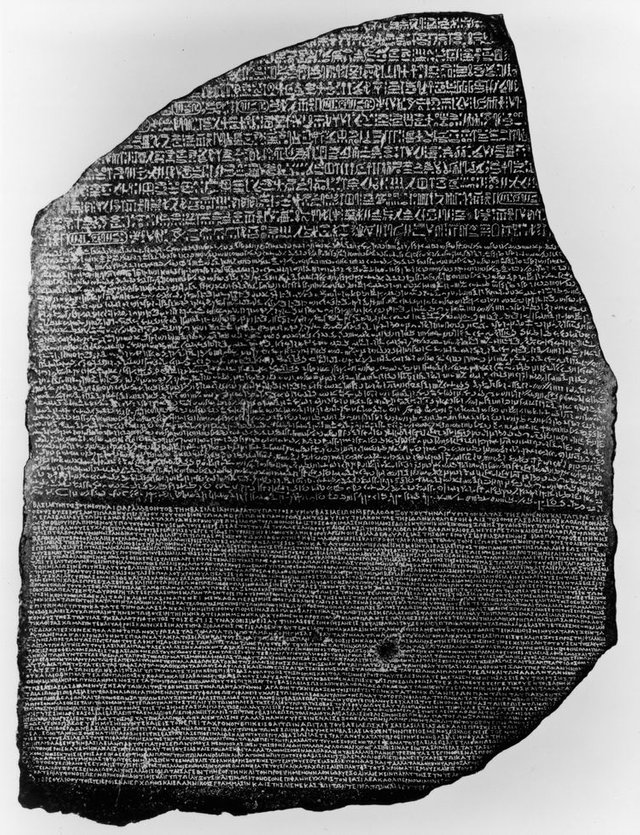

Currently, Western institutions in countries with imperial legacies remain at the center of these conversations about the surrender of sensitive objects: England, France, Germany and, to a lesser extent, the United States. The British Museum houses the Rosetta Stone, which they report was found in Egypt by Napoleonic troops during a conquest in 1799, as well as the Parthenon Marbles that Thomas Bruce, the seventh Earl of Elgin, took from Greece in the early 1800s when he was ambassador to the Ottoman Empire. Egyptologists and representatives from Greece now vehemently request their returns. The British Museum also houses 23,000 priceless artifacts in their China collection, some of which were looted from Beijing in the 19th century; a Gweagal shield that Captain Cook collected from indigenous Australians in 1770; and a controversial Hoa Hakananai'a statue from Easter Island. The institution justifies their ownership of items like the Rosetta Stone by stating that it "[allows] a global public to examine cultural identities and explore the complex network of interconnected human cultures" within the galleries, said a spokesperson from the British Museum. As of this writing, they have not currently publicized any plans for the return of any of those objects.

Across town, the V&A houses priceless Ethiopian artifacts that were taken by the British Army during the 1868 Abyssinian Expedition — including a royal gold crown once owned by Ethiopian Emperor Tewodros II and a solid gold chalice that was a gift to the Ethiopian Orthodox Church in Gondar. These items are being displayed with increased transparency in a new exhibit called Maqdala 1868, which will run until July 2019. The exhibit, which lives in the V&A's silver galleries, was curated along with a statement that the museum configured to enable "a vital new understanding" of the collection's significance

For the exploited populations, these objects often represent a stolen history that can constantly be rewritten by the perpetrators — as long as they retain the spoils. This is why, for many, repatriation represents the only true way to begin acknowledging past transgressions.

The Louvre, for example, currently houses Egypt's Zodiac of Dendera, long believed to be the oldest zodiac in the world. Egyptian archaeologist and former Minister of State for Antiquities Affairs, Dr. Zahi Hawass, demands its return. As he points out, Egypt is already plenty accommodating to Western institutions. "We sometimes give our artifacts [to] loans and exhibitions...we open the country for Europeans to excavate and work; all of this is done willingly without asking for anything back," he writes over email. "Therefore, if we ask for unique artifacts to be in their home country, this is completely legal and reasonable."