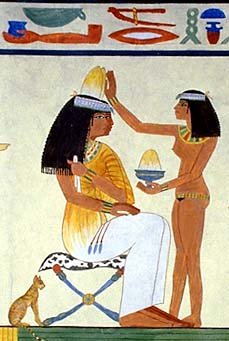

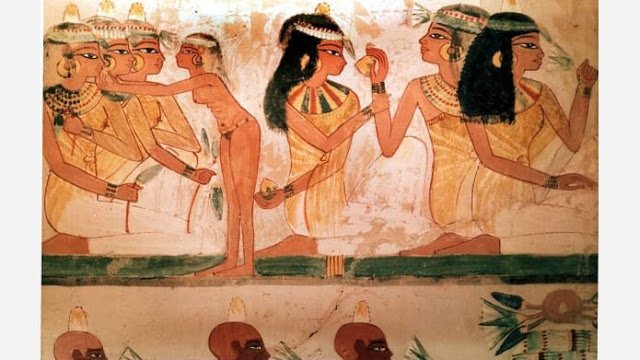

Punic Wax is the Beeswax Soap Cone on their heads in the Heiroglyphs

Punic Wax in Ancient Egypt was use to symbolize Rebirth and Creation, the cycle of Destruction, Preservation and Creation. It was used to hold Wig styles and make Dreadlocks, as well as Shampoo. And just by looking at the drawings by the Heiroglyphs you can see it was allowed to run onto the clothes and may have been how Egyptians designed their clothing. Beeswax was also used for most amulets, and statuettes, or used to make casts for metal. The Sun is the Bee God.

I first posted the recipe on Steemit here

https://steemit.com/science/@punicwax/discovering-punic-wax

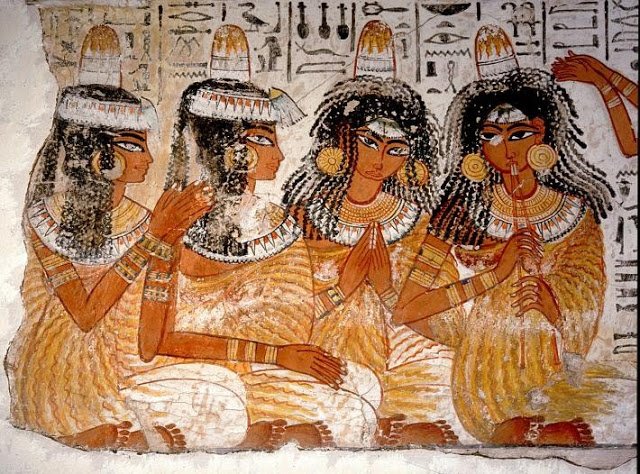

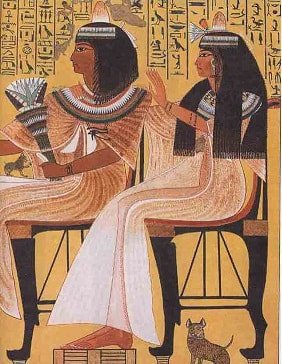

"When we are looking at the feast scenes that are displayed on the walls of ancient Egyptian tombs, definitely noticeable are pale yellow hills that are depicted above heads of the feast participants. Generally, these hills are perceived as decorations of egyptian wigs. Seems like this had been quite the widespread and characteristic fashion element during the times of New Kingdom.

Researchers of ancient Egyptian culture and art based their conclusions on the quite recent discovery of archaeologists. In accordance with that, ancient Egyptian wig decorations have been named as "perfume cones." However, this bizarre arrangement on their wigs is so unique that it should be regarded as an old-time fashion accessory. Perfume cones once were used as symbolic and quite decorative items, but they also had an important functional role.

Odoriferous cones Egyptians began to use in the times of the New Kingdom. In particular, perfume cones became common during the time of 18. dynasty as evidenced by the many tomb paintings in which we can see feast participants - musicians and dancers, as well as guests. They are all wearing these strange cones on their heads.

It turns out that perfume cones could be made of creamy scents. However, it is seems like the cones that are used as decorations on Egyptian wigs during The New Kingdom were made from either aromatic resin, or ox fat impregnated with myrrh. During the feast, these cones, slowly melting, released a sweet aroma. It was a tradition among men and women to adorn their heads with perfume cones especially during the feasts and celebrations. In addition, in ancient Egypt it was the usual habit to offer those perfume cones to guests, as soon as they arrived at the celebration place. The guests received those refreshing perfume cones that were soaked in, aromatic substances, creating truly the right environment for celebrations.

Modern experiments showed that perfumed beeswax, essential oils and fats could also be used in Ancient Egypt. According of today's people's idea, all the substances mentioned above, were carried on the heads of Ancient Egyptians during the celebration. When nightly events started, these cones gradually melted, spreading a wonderful and sweet aroma, as well as these perfumes seemed as pleasant refreshments to guests... just like lemonade or any soft drink.

Judging from the tomb paintings as seen in the examples, quite noticeable are yellow flower petals on the top of some cones.

Hieroglyphs message from an ancient Egyptian stone stele is quite clear - "perfume on their heads."

According to some researchers' opinion, perfume cone usage in ancient Egypt is rather linked to the symbolic and aesthetic perceptions. It shows the fragrance concept itself - the physical, sensual and aesthetic aspects. Perfume has been widely applied in many Egyptian religious rituals, funerals, embalming and, of course, during the feast, where emphasis was placed on stimulating, sexuality-building role of perfume."

"It took scholars nearly a decade to secure funding and complete a substantial examination of the head cones, giving them a chance to test another popular theoryabout the unusual objects: The head cones were actually solid lumps of perfumed fat that melted over the heads of their wearers and acted as a sort of ancient, fragranced hair gel.

The findings from Amarna seem to negate the ancient styling product theory. The cones weren’t solid—they were hollow shells folded around brown-black organic matter the team thinks may be fabric. Both head cones had chemical signatures of decayed wax; the team concluded they were made of beeswax, the only biological wax known to be used by ancient Egyptians. Furthermore, no traces of wax were found in the hair of the most well-preserved skeleton.

Given artistic associations of the objects with childbirth, and the fact that at least one of the specimens was an adult woman, the team suggests the cones had something to do with fertility. But the fact that they were found in a non-elite cemetery makes it difficult to interpret the meaning behind them."

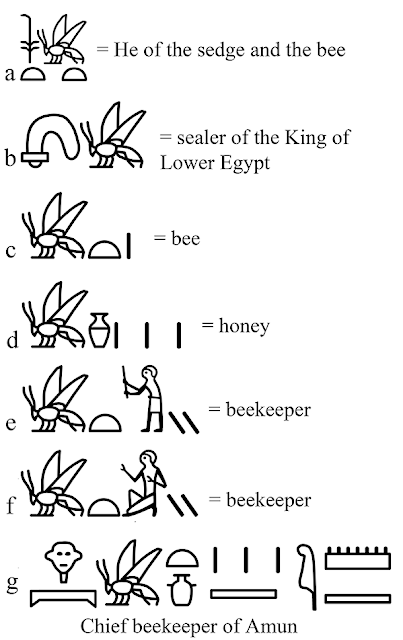

"It cannot be disputed that the Ancient Egyptians attached great religious and spiritual significance to the honey bee. Bees were associated with royalty in Egypt; indeed, as early as 3500 BC, the bee was the symbol of the King of Lower Egypt! (The symbol of the King of Upper Egypt was a reed). There are many examples of bee hieroglyphs to be found in the records, as well as hieroglyphs for honey and beekeeper.

Beekeeping has been practiced for thousands of years in Egypt. For at least four thousand five hundred years, the Egyptians have been making hives in the same way, out of pipes of clay or Nile mud, often stacked one on top of another. These hives were moved up and down the Nile depending on the time of year, allowing the bees to pollinate any and all flowers which were in season. Special rafts were built for moving these hives, which were stacked in pyramids. At each new location, the hives were carried to the nearby flowers and released. When the flowers died, the bees were taken a few miles further down the Nile and released again. Thus the bees traveled the whole length of Egypt. This tradition continues into the present day.

Honey and wax were used for religious as well as practical purposes. Sacred animals were fed cakes sweetened with honey. These animals included the sacred bull at Memphis, the sacred lion at Leontopolis, and the sacred crocodile at Crocodilopolis. Mummies were sometimes embalmed in honey, and often sarcophagi were sealed up with beeswax. Jars of honey were left in tombs as offerings the dead, to give them something to eat in the afterlife. One of our favorite stories to tell kids is that when King Tut's tomb was open, a 2,000-year-old jar of honey was found. And because honey never spoils, it was still perfectly edible!

It was widely believed in Ancient Egypt that if a witch or a wizard made a beeswax figure of a man and injured or destroyed it, the man himself would suffer or die. In a ceremonial offering known as the "Opening of the Mouth", priests used special instruments to place honey into the mouth of a statue of a god, or the statue or mummy of a king or other great noble. Certain lines in ancient rituals indicate that the Egyptians may have even believed that the soul of a man (his "ka", or double; the part which continues after death) took the form of a bee. Another ritual from the Book of "Am-Tuat", or "the Otherworld", compares the voices of souls to the hum of bees.

It was written in another ritual, contained in the "Salt Magical Papyrus", that bees were created from the tears of the sun-god Ra himself, whom the Egyptians believed to be the creator of the earth and the sea. Ra's right eye was the sun, his left eye was the moon, and he caused the Nile to flood.

"When Ra weeps again the water which flows from his eyes upon the ground turns into working bees. They work in flowers and trees of every kind and wax and honey come into being.""

-https://www.planetbee.org/planet-bee-blog//the-sacred-bee-bees-in-ancient-egypt

"The unique physical properties of beeswax; water-resistance, malleability and a low melting point, made it useful to the ancient Egyptians in a number of ways.

Beeswax was used to preserve the curls and plaits in wigs and could be used as a face cream. In medicine it was used as an adhesive for bandages and to bind active ingredients into pills. Boats were waterproofed with beeswax and complex metal shapes were created using the ‘lost wax’ casting technique.

The properties of beeswax also created a number of symbolic associations for the Egyptians. Its malleability made beeswax a perfect metaphor for creation in religious rituals, allowing an individual to embody the god Khnum who modelled life out of clay. Wax could also be used to mimic life-like features such as hair and skin in art. For the Egyptians this reinforced the idea that beeswax was imbued with life-giving properties.

Consequently beeswax was also connected to Egyptian ideas about the sun and its symbolism, further strengthening its associations with new life.

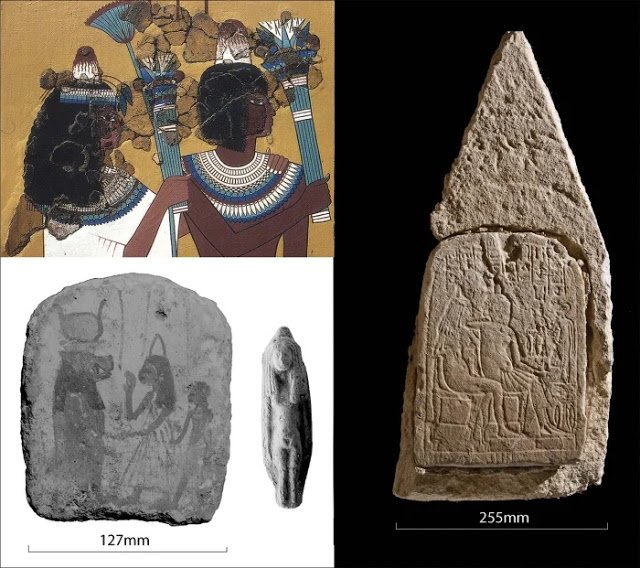

This relationship between the symbolic and practical qualities of beeswax can be seen especially well in the use of beeswax models.

Beeswax models were used for a wide range of religious practices. Some of the best documented are execration rituals. Execration rituals involved the symbolic destruction of an enemy through the actual destruction of an object bearing the enemy’s likeness. The lifelike qualities of wax made it a perfect material for these rituals as models could be made to look as much like the enemy to be destroyed as possible, adding realism and power to the symbolic destruction.

This realism also lent power to beeswax when it was used to symbolise new life. From the New Kingdom into the Third Intermediate Period beeswax benu birds were placed in tombs to encourage rebirth in the afterlife.By the Late Period benu bird moulds with traces of beeswax were also placed in tombs. One of the beliefs held by Egyptians about the benu bird was that its call had summoned life into an empty world of dark waters, tying it to the same ideas of new life and renewal ascribed to beeswax.

Other wax objects placed in tombs and intended to imbue life to the deceased included amulets such as ankhs made of beeswax and coated in gold. Wax models of the four sons of Horus were also placed in tombs in the Third Intermediate Period when canopic jars became less common. These wax figures served to protect the organs of a mummified individual for use in the afterlife. As with the amulets and the benubird figures these sets could be produced en masse due in part to wax’s low melting point and malleability. This once again demonstrates the material’s physical properties harmonising with its symbolism.

The magical applications of beeswax figures are also mentioned in a number of Egyptian texts. In Papyrus Westcar a priest is recorded as bringing a wax crocodile to life to eat his wife’s lover and in papyri Lee and Rollin the suspects in Ramses III’s harem conspiracy are accused of making wax models to ‘disable and enfeeble the limbs’.

Beeswax would therefore have been a common sight in Egyptian life, in religion, in medicine, in shipbuilding, beauty, magic and art. Its properties made beeswax useful in a wide range of industries but also imbued it with special meaning focusing on life and vitality. Consequently the symbolic applications of beeswax can be seen to have been as real to the Egyptians as their practical uses without one ever belittling the other. This allowed beeswax to exist as both a material to be used and respected as a substance with special meaning depending on the situation. Consequently it existed simultaneously as a special and a ubiquitous part of Egyptian life."

-https://birminghamegyptology.co.uk/virtual-museum/objects-come-to-life/articles/life-through-wax/

"Tomb paintings show beekeepers removing round honeycomb from the horizontal hives. The honeycomb was crushed and then placed into containers.

“So, of course, I had to do this,” Kritsky says. “I took honeycomb and I crushed it, and I put it in a container in the hot sun and the beeswax floated to the top and the honey stayed below the beeswax.”

Another relief shows beekeepers holding a vessel with a spout coming from the middle or towards the bottom, Kritsky says — much like a fat separator used for making gravy. “That may be one way they could have decanted a lot of the honey without getting a lot of the wax mixed in with it,” he explains.

In one of the oldest tomb paintings, from 2450 BCE, a beekeeper is holding something to his face, right up against the opening of the hive.

“The hieroglyph above it means “to weaken” or “to slacken” or “to emit a sound,” Kritsky says. “That’s been interpreted as smoking bees, which is a way of quieting bees, or maybe calling to the bees.”

In fact, scholars believe a traditional Egyptian beekeeper practice involved ‘calling’ the queen — making a sound to see if the queen bee would respond. “That would tell them if there was a queen ready to emerge or the status inside the hive,” Kritsky explains. “If that was the case, then their beekeeping was much more sophisticated than we can appreciate.”

Egyptians had various uses for beeswax, too. Beeswax was used in cosmetics, as well as in paintings, and even in some embalming practices.

Beeswax was also important as a “wonderful, magical substance,” Kritsky says. “Beeswax burns with a very bright light and doesn't leave any ash. Moreover, if you put beeswax in the hot Egyptian sun, it will start to change. It will get a little molten, a little liquid-y. All of this tied in with their solar theology and would have been important to the Egyptians.”"

-https://www.pri.org/stories/2015-12-02/what-we-can-learn-ancient-egyptian-practice-beekeeping

"All ancient Egyptian wax is beeswax, either pure or with resin, oil or other pigments. There was evidently a strong belief that, as a malleable material easily burned, wax is powerful, especially for inflicting change or harm on a creature. Many of the most colourful written references come from Ptolemaic and Roman Period sources, when influences from abroad may have taken hold.

A tale about Alexander the Great, written by the 'pseudo-Callisthenes', describes that Nectanebo II was a great magician: the king used wax figures in secret rooms of his palace, to defeat the armies of his enemies. In a Greek magical papyrus (Leiden inv. AMS. 75, cat. I 384 - 4th century AD) is described the making of a group of wax and herb figures of Eros and Psyche, to gain power over all men and women.

No wax figures certainly associated with incantations have survived. The earliest wax figures found date to the First Intermediate Period (about 2100 BC), and come from a funerary context. These are small human figures, perhaps representing the dead. Especially many wax figures are know from the Late, Ptolemaic and Roman figures; some may be from metal-casting procedures rather than religious in function. However, the most common images from these periods are amulets in the form of the four children of Horus, placed on mummies. In the Ptolemaic and Roman Periods Egyptian amulets are often made in wax, sometimes gilt."

-https://www.ucl.ac.uk/museums-static/digitalegypt/burialcustoms/wax.html

"The work on over 6,400 prehistoric vessels has specified the where and when of the first uses of beeswax. Now we know that the oldest evidence of it is to be found in Neolithic sites in Anatolia (Cayonü) in the seventh millennium BCE, in other words, corresponding to the oldest pottery cultures in the region. It is in this same area that the famous Çatalhöyük settlement is located and from which comes an ancient pictorial depiction of a bees’ nest. The use of beeswax has also been detected in prehistoric populations in the north-west of Anatolia; it has been dated between 5,500 and 5,000 years BCE often mixed with the fat of ruminants.

In Europe the first known finds are somewhat later: in Greece around 4900-4500, in Rumania from 5500-5200 onwards, and in Serbia in 5300-4600. We are aware of its use round about the same time in Central Europe in the Neolithic culture of Austria and Germany. More recent are the French and Slovenian cases. On the Iberian Peninsula the 130 receptacles analysed have not preserved any remains of wax, so it is necessary to conduct further research given than in Levantine art there are various depictions of bees: “You have to bear in mind the fact that the detection of signs of lipids of the wax inside the vessels is very low and that the number of receptacles analysed in Iberia is still very low,” but the logical thing is that the bees would also have found suitable environments to develop on the Iberian Peninsula since the beginnings of farming, in other words, about 5,500 years ago,” added Alday."

-https://americanbeejournal.com/first-human-uses-beeswax-established-anatolia-7000-bce/

"The story of Egyptian Magic begins in 1986 at a Chicago diner when an elderly man approaches Westley Howard, a water filter salesman who is passing through. “He said, ‘Brother, the spirit has moved me to reveal something to you,’” said Mr. Howard, as Mr. ImHotepAmonRa was then known. “It didn’t seem too weird to me. I’m a spiritual person, so these things happen to me all the time.”

The stranger’s name was Dr. Imas. He never revealed his first name or made it clear what kind of doctor he was. Over the next two years, Dr. Imas periodically visited Mr. Howard in Washington and showed him how to make a skin cream from olive oil, beeswax, bee pollen, royal jelly and bee propolis (a substance that seals hives).

Dr. Imas claimed it was the exact same formula for a cream found in ancient Egyptian tombs. There is some basis to the mixture’s pharaonic claim. Beeswax was a popular ingredient in ancient Egyptian cosmetics, as was olive oil, which has been used as a cleanser, moisturizer and antibacterial agent for centuries, said Bernie Hephrun, a researcher of Egyptian cosmetics in Reading, England.

Mr. Hephrun, who has worked to recreate unguents found in ancient tombs for several European universities, is impressed with Egyptian Magic. But he did voice one qualm: “Ancient Egyptians didn’t have the ability to separate out pollen, jelly and propolis.” Still, he said, “It has long been believed that Alexander the Great was preserved in honey when he died.”

Where did Dr. Imas come upon this formula? “He said it was revealed to him the way he was revealing it to me,” Mr. ImHotepAmonRa said.

Stuart Henigson, a spokesman for Egyptian Magic, added that Dr. Imas “was looking for someone who could take it to a larger audience.” He was adamant that Egyptian Magic be rolled out in a particular way. “Word of mouth only, no paid advertising or endorsements,” Mr. Henigson said.

“I probably tell people about it at least once a day,” said Bob Litvak, an owner of Santa Monica Homeopathic Pharmacy, a longtime supplier. He said the product’s devotees tell him that Egyptian Magic “prevents diaper rash, it’s good for sunburns, chemical burns, and oven burns, and” — Mr. Litvak paused as someone in the store reminded him of another use — “Oh, it’s a good feminine lubricant.”"

-https://www.nytimes.com/2007/09/27/fashion/27SKIN.html

"Legend has it that when she first visited Marc Antony in Tarsus, she coated the purple sails of her golden boat in a fragrance so pungent that it wafted all the way to shore. As Shakespeare wrote, Cleopatra’s sails were “so perfumèd that the winds were lovesick with them.” It does sound a bit extra, but, honestly, who wouldn’t want to catch a whiff of Egypt’s most famous queen?

Littman and his colleague Jay Silverstein came up with the idea during their ongoing excavation of the ancient Egyptian city Thmuis, located north of Cairo in the Nile Delta and founded around 4500 BC. The region was home to two of the most famous perfumes in the ancient world: Mendesian and Metopian. So when the researchers uncovered what seemed to be an ancient fragrance factory—a 300 BC site riddled with tiny glass perfume jars and imported clay amphoras—they knew they had to try to recover any scent that had survived.

The amphoras did not contain any noticeable smell—but they did contain an ancient dried residue (analysis of which is pending). Dora Goldsmith and Sean Coughlin replicated the Thmuis scent using formulas found in ancient Greek materia medica and other texts.

Both Mendesian and Metopian perfumes contain myrrh, a natural resin extracted from a thorny tree. The experts also added cardamom, green olive oil, and a little cinnamon—all according to the ancient recipe. The reproduced scent smells strong, spicy, and faintly of musk, Littman says. “I find it very pleasant, though it probably lingers a little longer than modern perfume.”

In ancient Egypt, people used fragrance in rituals and wore scents in unguent cones, which were like wax hats that dripped oil into one’s hair over the course of the day. “Ancient perfumes were much thicker than what we use now, almost like an olive oil consistency,” Littman says. “Cleopatra made perfume herself in a personal workshop,” says Mandy Aftel, a natural perfumer who runs a museum of curious scents in Berkeley, California. “People have tried to recreate her perfume, but I don’t think anybody knows for sure what she used.”

Aftel is no stranger to the concocted scents of ancient Egypt. In 2005, she reproduced the burial fragrance of a 2,000-year-old mummified Egyptian child, a girl dubbed Sherit. Since her mummification, the perfume had shriveled into a thick black tar around Sherit’s face and neck, according to a Stanford press release. Aftel identified frankincense and myrrh as the primary ingredients in the perfume and reconstructed a copy. “I smelled the mummy,” Aftel says. “As a natural perfumer, it’s a very beautiful way to connect to the past.”"

-https://www.atlasobscura.com/articles/cleopatras-ancient-perfume-recreated

INGREDIENTS

"Kyphi (Kapet) was one of the most popular types of temple incense in Ancient Egypt and it was also used as a remedy for a number of ailments. The name Kyphi is actually the latin version of the Greek transcription of the egyptian word Kapet and it is thought that it originally referred to any substance used to clean and perfume the air only later developing into a specific type of incense. Kyphi is still best considered as a type of incense rather than a specific recipe as the ingredients listed in ancient sources, both Egyptian and later Greek and Syrian, are varied with only a few ingredients appearing in every recipe. We have four complete recipes for Kyphi, two of which are in Greek and date to later periods, but sufficient information to hazard a guess at a further three recipes.

It is difficult to confirm the identity of some of the ingredients of Kyphi, but based on the information avaiable Kemet Design has developed Kyphi (Kapet) incense which is as similar as possible to the traditional incense of Ancient Egypt.

The earliest recipe for Kyphi Ebers Papyrus (circa 1500 BC). This recipe was intended to be used to purify the home and give clothes and breath a pleasant aroma so may have differed a little from the recipes used by temples at the time. Most notably, there is no mention of raisins in this recipe (although it is possible that the inclusion of raisins was assumed) and the Kyphi is prepared by simply boiling the ingredients in honey.

Papyrus Harris I was composed during the reign of Ramesses IV during the twentieth dynasty (Ptolemaic Period of Ancient Egypt). The papyrus records the donations made by Ramesses III to a number of temples and refers to the delivery of six of the ingredients found in the Edfu recipe to temples so that they can prepare Kyphi. The ingredients listed are mastic, pine resin (or wood) camel grass, mint, sweet flag and cinnamon. It is assumed that the recipe would also have included raisins wine and honey but that theses supplies would not have to be delivered from the central stores as the temples would be able to source them locally. Unfortunately the papyrus Harris does not confirm the recipe or the method of preparation.

Plutarch visited Egypt durint the first century BC (the Ptolemaic Period of Ancient Egypt). He had access to a text by Manetho (third century AD) called “Preparation of Kyphi-Recipes” no copies of which have been recovered. Plutatch quotes a recipe from this important text and clarifies the method of prearation of Kyphi. According to Manetho the ingredients are not added at the same time and ground, but rather added one at a time as magical texts are read aloud.

Plutarch also confirms that Kyphi was drunk to cleanse the body and was thought to bring restful sleep with vivid dreams. According to Plutarch Ancient Egyptian priests burned incense in the temple three times a day: frankincense at dawn, myrrh at midday, and Kyphi at dusk.

The Temple of Edfu was built in the first century BC (the Ptolemaic Period of Ancient Egypt). There are two different recipes for Kyphi inscribed on the walls of the temple, one of which includes synonms for many of the ingredients and explanatory notes. The two recipes differ only in the quantities of each ingredients. A similar recipe (again with the same ingredients but in slightly different quantities) can be found on the walls of the Temple of Philae.

The preparations of these recipes is much more complex than the later Greek versions and there are also more ingredients. The mastic, pine resin, sweet flag, aspalathos, camel grass, mint and cinnamon are ground together in a mortar and the liquid residue discarded. Then the cyperus, juniper berries, pine kernels and peker are ground to a fine powder and combined with the mastic mixture. The combined mixture is moistened with a little wine and left to steep overnight. The raisins are steeped in wine and combined with the mixture and this is allowed to steep for a further five days. The mixture is then boiled until it has reduced by one fifth and the honey and frankincense are combined and boiled to reduce by one fifth. The two mixtures are combined and the myrrh is then ground and added to make the final mixture which was formed into small pellets for burning.

Papyrus Ebers

Honey

Frankincense (antiu)

Mastic

Genen (Sweet Flag)

Pine Kernels

Cyperus Grass

Camel Grass

Inektun

Cinnamon

Papyrus Harris

(Raisins)

(Wine)

(Honey)

Mastic

Pine Resin

Camel Grass

Mint

Sweet Flag

Cinnamon

Manetho

Raisins

Wine

Honey

Myrrh

Resin

Mastic

Bitumen of Judea

Cyperus

Aspalathos

Seseli

Rush

Lanathos

Sweet Flag

Cardamom

Edfu Temple

Raisins

Wine

Honey

Frankincense

Myrrh

Mastic

Pine Resin

Sweet Flag

Aspalathos

Camel Grass

Mint

Cyperus

Juniper Berries

Pine Kernels

Peker

Cinnamon

Galen (circa 200 AD) studied medicine in Alexandria and so had access to many of the texts from Ancient Egypt which have since been destroyed. He wrote an essay called “On Antidotes” which refers to a scroll written by Damocrates (now lost) in which Damocrates confirmed that he had used the recipe for Khypi set down by Rufus of Ehpesus (circa 50AD) which he includes in his scroll.

To make Kyphi Rufus advised that the honey and raisins should be mashed together. Then the bdellium and myrrh should be ground with some wine until the mixture had the consistency of runny homey before being combined with the honey and raisin mixture.the rest of the ingredients could then be ground and added and the incense formed into pellets for burining.

Damocrates also confirms that according to Rufus cardomom may be a substitute for Cinnamon and that the mixture was used to purify the temple but also as a remedy for snakebite.

Dioscorides (circa 100 AD) provides us with a recipe for Kyphi in “De Materia Medica” and this is thought to be the first Greek description of the material. He confirms that Kyphi was primarily used to purify the temple but was also made into a drink which was taken as a remedy for asthma. He notes that there are a number of recipes for Kyphi and quotes one of them.

Raisins, wine and myrrh are ground together. The remaining ingredients (except the honey and resin) are ground together and added to the raising mixture and the resulting mixture is left to steep for a day. The resin is then melted slowly with the honey and then ground into the first mixture.

There are no exotic spices in this recipe and is is proposed by Manniche that this recipe was primarily an antidote rather than an incense recipe. She suggests that the exotic spices were not considered necessary for the medicinal use of Kyphi but would have been used to enhance the aroma of Kyphi when it was prepared as incense

Around the time of Galen (circa 200 AD) an unnamed scholar was compiling a book on medicine in Syriac (Aramaic). He made refenece to a substane named “Kupar” whicb is thought to be a version of Kyphi. He advises that the rasins and other soluble ingredients should be dissolved in wine. The dry ingredients are then ground in a mortar and the frankincense and honey are warmed together. All of the ingredients are then combined.

Kupar is described as an incense with a very plesant aroma and a remedy for liver disease, and for coughs and other diseases affecting the lungs.

Rufus of Ephesus

Raisins

Wine

Honey

Burnt Resin

Bdellium

Camel Grass

Sweet Flag

Cyperus Grass

Saffron

Spikenard

Aspalathos

Cardomom

Cassia

Dioscorides

Sun Raisins

Old Wine

Honey

Myrrh Pure Resin

Juniper Berries

Sweet Flag

Camel Grass

Aspalathos

Cyperus Grass

Syriac

Raisins

Wine

Honey

Frankincense

Myrrh

Spikenard

Crocus (saffron)

Mastic Aspalathos

Cinnamon

Cassia"

-https://ancientegyptonline.co.uk/kyphi/

"Yet ancient Egyptians didn't only apply makeup to enhance their appearances -- cosmetics also had practical uses, ritual functions, or symbolic meanings. Still, they took their beauty routines seriously: The hieroglyphic term for makeup artist derives from the root "sesh," which translates to write or engrave, suggesting that a lot of skill was required to apply "kohl" or lipstick. The most refined beauty rituals were carried out at the toilettes of wealthy Egyptian women. A typical regimen for such a woman living during the Middle Kingdom (ca. 2030-1650 B.C.) would have been indulgent, indeed. Before applying any makeup, she would first prepare her skin.

She might exfoliate with Dead Sea salts or luxuriate in a milk bath -- milk-and-honey face masks were popular treatments. She could apply incense pellets to her underarms as deodorant, and floral- or spice-infused oils to soften her skin. Egyptians also invented a natural method of waxing with a mixture of honey and sugar. "Sugaring," as it's called today, has been revived by beauty companies as a less painful alternative to hot wax.

These apparatuses, containers and applicators were themselves lavish art objects that communicated social status. Calcite jars held makeup or unguents and perfumes and containers for eye paint and oils were crafted from expensive materials like glass, gold or semi-precious stones. Siltstone palettes used to crush materials for kohl and eyeshadow were carved to resemble animals, goddesses or young women.

These symbols represented rebirth and regeneration, and the act of grinding pigments on an animal palette was thought to grant the wearer special capabilities by overcoming the creature's power. (Members of the lower classes used more modest tools when applying their own makeup.)

The servant would create eyeshadow by mixing powdered malachite with animal fat or vegetable oils. While the lady sat at her toilette, before a polished bronze "mirror," the servant would use a long ivory stick -- perhaps carved with an image of the goddess Hathor -- to sweep on the rich green pigment. Just as women do today, eyeshadow would be followed with a thick line of black kohl around her eyes.

This part of the routine had practical purposes beyond beautifying the wearer. Kohl was used by both sexes and all social classes to protect the eyes from the intense glare of the desert sun. The Egyptian word for "makeup palette" derives from their word meaning "to protect," a reference to its defensive abilities against the harsh sunlight or the "evil eye." Additionally, the toxic, lead-based mineral that it was made from had antibacterial properties when combined with moisture from the eyes.

The final touches to this lady's makeup would, of course, be red lipstick -- a classic look even today. To make the paint, ochre was typically blended with animal fat or vegetable oil, though Cleopatra was known to crush beetles for her perfect shade of red."

-https://www.cnn.com/style/article/ancient-egypt-beauty-ritual-artsy/index.html

Images used are Ancient, for educational purposes to show wax on their head.

@steemcurator01

@steemcurator02

Downvoting a post can decrease pending rewards and make it less visible. Common reasons:

Submit