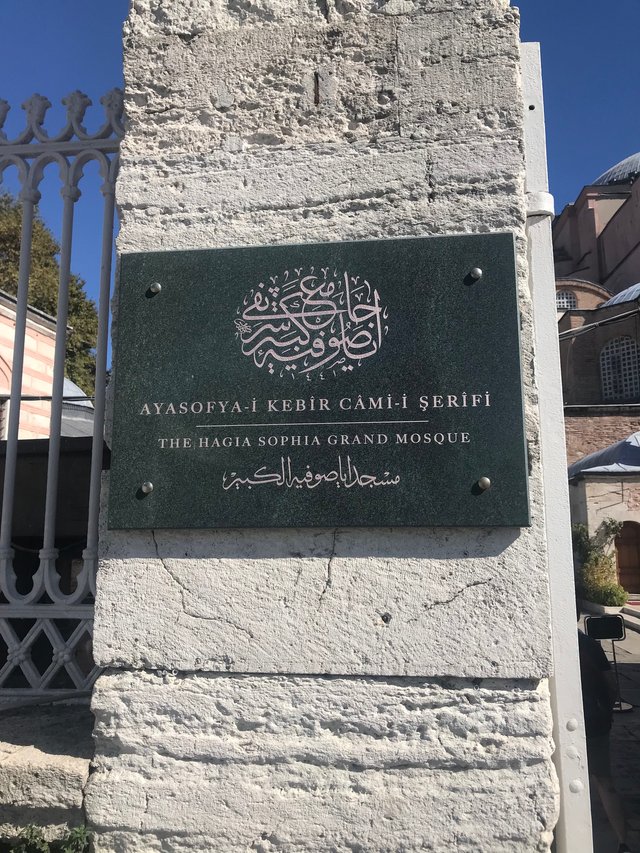

The Jewel of Istanbul: Entering the Hagia Sofia.

I've only ever felt this way a few times before. The weight of something important bore down on me with a strange but unwavering intensity. As I slipped off my shoes, I glanced at my hands to see if they were shaking. They were still steady, but inside, I was greatly moved.

I can tell you that as this was my first time entering a Mosque, I didn't know what to expect. And I was also a bit nervous. Me, a non-muslim, in a foreign land, indeed, a Westerner. I was about to enter the sacred Mosque of the Islamic faithful. And I was unsure of my welcome.

A large tunnel sloped downward from the outside to the anteroom. Over a massive doorway constructed of stone, marble trim and relief sculptures adorn. One thousand four hundred sixty-five years ago, the first worshipers of this wonderous place strolled through for the first time to practice their religion. They must have been in as much awe as I was on this day. And I had far more in common with them than I did with the faithful who flocked here today.

Vestibule Mosaic

I stepped aside from the crowd that made their way steadily inside. Looking up, I saw the Vestibule Mosaic, which has stood guard over this doorway since around 1000 AD.

In this plaster collage, the Virgin Mary holds the Christ child in her lap. Justinian, the former Emperor of Constantinople, is handing Mary a replica of the newly constructed basilica to the viewer's left. To our right is Constantine, then the current Emperor of the Eastern Roman Empire. Constantine is offering Mary and her son the entire city as a sign of reverence and respect.

Each of the figures is accompanied by inscriptions that seem a veiled attempt at one-upmanship. Justinian's reads,' Justinian, Emperor of Illustrious Memory". Next to Constantine reads, "Constantine, the great Emperor amongst the saints." Of course, trumping both are monograms over Mary's head which signify, "The Mother of God."

Overhead, elaborately painted designs in gold, teal, and earth colors decorate the ceilings. These designs, nearly 1500 years old, show the wear and tear of the elapsed centuries. Still, they remain a commanding presence in this space. There is a simple, almost crude, element to them compared to Turkish tile's rich perfection in other mosques. Handpainted and lacking the ideal of contemporary machine-made patterns, these ceilings have still outperformed and outlasted most modern-day constructions that would rival them.

I finally pass through the massive gate, star-struck by the two giant wooden doors hinged there. Approximately eight inches thick, these doors meant business to any unwanted entry. I stopped again to look back through the doorway, with streams of bright light cascading in. Flat stone, cracked and discolored by millions of footsteps, led back out and up a slight rise to the street outside.

Muslim women and men passed through and around me, cameras and cellphones in hand. The women wore head coverings. Everyone wore silence. And no one so much as glanced my way as I took pictures and gazed around me, savoring these steps into the Mosque.

The Vestibule of Hagia Sofia

Finished with my extensive examination of the vestibule entry, I rotated and stepped further inside. The walls are clad with decorative panels. A series of doorways led into the central area of the Mosque, most closed to the public save for two; one for entry, the other for exit.

Looking up, an ornate series of arches ran the entire length of the vestibule. Primarily protected from the elements, these ceilings were in far better shape than their exterior cousins but not unscathed.

These ceilings are painted in rich gold, with faded blue, handpainted, crisscrossing lines and floral patterns in repetition. Despite a series of large, illuminated circular fixtures and high arches allowing in the sun, the vestibule remained darkened and solemn.

An extensive wooden cabinet of unknown age silently called for our footwear along one wall. The passage between a rail separating the cabinet from the main walkway was narrow and allowed only two or three persons to pass through at a time. I slipped off my loafers and held them in my hand, waiting for my opportunity to pass and to store them. Footwear is not allowed in Mosques.

A small group of Muslim men and women also waited beside me as the knot of people attempted to clear the narrow gap. Once there was an opening, I waved gently to the small group, and with a smile and nods of heads to me, they passed through to place their sandals and shoes in the cabinet. My unprovoked feelings of being a trespasser here diminished with the implicit gratitude and flicker of warmth offered by these fine folks. I had never been so grateful for a show of simple acknowledgment as a human being before.

I placed my shoes gently on top of the box.

I walked toward the far end of the vestibule. In the act of delayed gratification, I did not look into the Mosque as I passed the massive entrance and exit doorways. My eyes were fixed firmly ahead, and I intended to drink in each aspect of the Mosque entirely before moving on to the next.

Before a barred door, another two sets of long wooden storage cabinets for footwear were at the far end of this vaulted anteroom. These, however, were free of the crush of eager visitors and were largely empty. However, the ceilings are better illuminated by the archway windows, and I snapped a few more shots with my camera phone. It was easier to make out the nautical designs in the tiled borders and to make out the tenth-century handiwork of plaster and paint.

Finally, I turned towards the broad doorways and prepared to enter the Mosque proper. With a deep breath, I walked towards the opening and had my first look at the interior ahead of me, careful of the steady stream of people making their way inside. I slid my ringer to silent and nervously held my phone to my side, unsure if I'd be told not to photograph inside.

Once in front of the doorway, I first noticed the high threshold of marble dividing the vestibule from the Mosque. It was worn completely smooth and modeled into wavy crevices by centuries of use. It appeared wet and was as slippery as ice. How many footsteps does it take to smooth marble to the smooth, rippled consistency of glass, I wondered? A million? A hundred million?

Immense wooden doors, five times the height of any man, led into the chamber. Whether constructed against man or beast, I knew not. In either case, the doors proved to be an ostentatious first salvo in grandeur and gaudy significance to what lay beyond them.

First Glimpse of Inside

And as I saw inside for the first time, most prominent were a dozen round, multi-lamped chandeliers providing golden rings of light. They cast a rich, haughty air to the scene. Hanging low and bright, they served to magnify the magnificence of the domed ceilings of this ancient place.

With my first careful step upon the worn, marble threshold, I entered the Church of Justinian I. The seat of the Patriarchate of Constantinople. The spoils of war, claimed by the victorious Sultan Mehmed the Conqueror of the Ottoman Empire.

I could feel that weight return to my mind and my heart. For a moment, I was frozen with it. Something incredible was happening. And then I realized it for what it was. It was the weight of history bearing down upon me. I was about to witness the single most important place I had traveled 5000 miles to Istanbul to see.

I was entering the Hagia Sofia and History. The Jewel of Istanbul.

To Be Continued...

Source Credit:

hagiasophiaturkey.com

wikipedia.org

Congratulations @braveboat! You received the biggest smile and some love from TravelFeed! Keep up the amazing blog. 😍 Your post was also chosen as top pick of the day and is now featured on the TravelFeed.io front page.

Thanks for using TravelFeed!

@smeralda (TravelFeed team)

PS: You can now search for your travels on-the-go with our Android App. Download it on Google Play

Downvoting a post can decrease pending rewards and make it less visible. Common reasons:

Submit