AREN'T PEDIATRIC PATIENTS JUST MINI-ADULTS?

Children are special patients. They are not “mini adults.” Children have different physiology than adults. They are not fully developed, and their growth and development can be delayed when they have to deal with chronic illness. Medications can also affect child development in a more harmful way than adult patients.

Additionally, physicians often have to manage not only the child, but the family. The parents of the child, as their guardians, will provide consent. However, the pediatric patient must also provide consent (or assent) to any procedures and treatment plans.

WHAT IS THE YOUNGEST AGE THAT A PERSON CAN BE DIAGNOSED WITH IBD?

About 25% of patients with IBD are diagnosed as children. There is an increasing prevalence of IBD in Canadian children over the past 2 decades. Although there has been an increase in IBD around the world, and especially in areas that are highly developed, the highest increase has been in the pediatric population, specifically young children. In very young children, there is a hesitation to classify patients as Crohn’s or ulcerative colitis. This is due to patients being diagnosed so early, as well as confounding diseases, especially monogenic immune diseases. Monogenic disorders are a spectrum of disorders , each of which is associated with a single gene. Most produce the onset of colitis symptoms in early childhood1. To conclude and answer the question, IBD or IBD-like disease has been diagnosed as early as 8 months of age.

WHAT ARE THE SYMPTOMS OF IBD AND HOW DO THEY DIFFER IN KIDS?

Typical clinical cymptoms of IBD that can present in adults and children:

- Abdominal pain

- Watery and bloody diarrhea

- Urgent, painful bowel movements

- Perianal disease—abscesses, fissures, fistulae, skin tags

- Fatigue, weight loss, poor appetite

- Fever, rash, mouth sores, arthritis

So what is different about IBD symptoms in children?

Children typically have more severe and extensive disease. A good example is ulcerative colitis. Shown in the figure on the right, the disease is extensive twice as often in children. There is also higher steroid resistance in kids.

Pediatric patients also have an increased emphasis on growth, development, and puberty. Kids with IBD often experience a delay in growth or puberty. This is not seen in adults (although adults can experience weight loss). Their symptoms can also change around the time of puberty or during monthly periods. This is thought to be due to changes in hormones or cytokines.

Kids have many other age-dependent considerations including future years of exposure to toxic medications, body image, and psychological issues.

WHAT CAUSES IBD AND WHAT ARE THE RISK FACTORS?

The cause of IBD is complex and not fully understood. There are many risk factors that influence whether or not someone will get IBD. There is a definite genetic component, as having a family history of IBD can predispose someone to developing it. There are over 200 susceptibility genes for IBD, many related to host microbe interactions. However, the overall impact of genetics only explains 15-20% of the heritable risk.

The environment, including lifestyle and diet, are also extremely important. There is a higher prevalence of IBD in Western and developed countries, as well as living in urban environments 2,3,4. Smoking has been linked to complications and extra-intestinal manifestations in IBD, both ulcerative colitis and Crohn disease5.

Additionally, a study of Asian populations found breast feeding, antibiotic use, having dogs, daily tea or coffee consumption, and physical activity as protective factors for either Crohn’s or ulcerative colitis6. Interestingly, the protective effects of antibiotics are unique to Asia, as a metastudy by Ungaro et al., found antibiotics to increase the odds of being diagnosed with Crohn’s.

Demonstrated in the figure, many of these genetic and environmental factors are suspected to exert their effects on the Immune response and therefore on IBD, through gut microbes. As such, Dr. Wine has suggested we have a more microbe focused view. The challenge with this, and any attempt made to understand IBD, is that once you have IBD, the inflammation exert effects back on each of the proposed “causes” or factors. So in a way, IBD itself is a confounding variable.

Another interesting discovery, appendectomy for an inflammatory condition is associated with a lower risk of ulcerative colitis8. The appendix was once thought to serve no function, however it was shown that it actually houses a reservoir of bacteria. One theory is that perhaps some ulcerative colitis patients have abnormal gut bacteria, and even when given antibiotics, the appendix is repopulating their bacteria with the “bad” bacteria, reducing effectiveness of the treatment. However, a study has found that first degree relatives of UC patients with appendectomies are also “protected”9. This indicates that there might be something else at play, such as a heritable factor that predisposes one to appendicitis and protects them from colitis. More research is both necessary and being conducted on the topic10.

INCREASING INCIDENCE: THE HYGIENE HYPOTHESIS

Why is the incidence of IBD (and other autoimmune disorders) increasing? One suggestion is the “hygiene hypothesis”, which essentially has to do with Western society now being too sterile. While this has led to decreased incidence of infectious diseases, it is thought that being exposed to infectious agents, microorganisms, and parasites aids the natural development of the immune system, and building “immune tolerance”. It is also possible that the infectious agents themselves may protect against immunological diseases11.

TREATMENT OF IBD IN CHILDREN

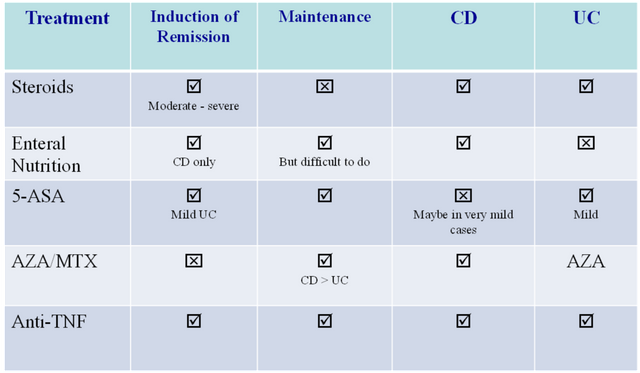

For the most part, similar medications are used in children with IBD as in adults with IBD. Most drug studies were conducted in adults, but through experience and a few clinical trials, they have been found to be safe and effective in children. For example, when first diagnosed with Crohn’s, the typical four options presented are:

- 5-ASA (for mild UC only)

- Steroids (effective, but lots of side effects, bone health/growth, neuropsychiatric effects, swelling of face, stretch marks, acne and more—steroids are generally avoided in kids)

- Azathioprine or methotrexate (maintenance therapy)

- Biologics

- Nutritional therapy (unique) – not a med, no side effects, safe, difficult to do.

WHAT ABOUT NUTRITIONAL THERAPY?

Nutritional therapy for Crohn’s disease is unique for children, in that it is highly effective, even though it has not been in adults. Instead of eating a normal diet, children are put on a strict regimented liquid diet. It has been shown to induce remission as effectively as steroids and is thought to work by removing food antigens that stimulate the immune system. Nutritional therapy provides excellent nutrition to the gut. It is liquid, and thus easier to tolerate for some Crohn’s patients who cannot tolerate solid chunks of food. It also affects gut bacteria because food is not stagnating in the bowel, and because food is already broken down.

However, this therapy is difficult to do because it is 8 weeks long. Two ways of taking nutritional therapy are 1) drinking it, and 2) placing a nasogastric tube. However, nutritional therapy can be monotonous, lacks flavor, and requires support and resources.

|

|

FUN FACTS

- Nearly 1 in 4 patients diagnosed are under 20 years old

- The exact cause of IBD is unknown but both genetic and environmental factors are involved.

- IBD can affect parts of the body outside the GI tract, such as the skin, joints, eyes, or liver.

REFERENCES

Uhlig, H. H. (2013). Monogenetic diseases associate with intestinal inflammation: implications for the understanding of inflammatory bowel disease. Gut 62: 1795-1805.

Aujnarian A, Mack D R, & Benchimol E I. The role on the Environment in the Development of Pediatric Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Curr Gastroenerol Rep. 2013 May;15(326).

Frolkis A et al. Environment and the Inflammatory Bowel Disease. CJG. 2013 Mar; 3:e18-e24.

Ng S C et al. Geographic variability and environmental risk factors in Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Gut. 2013;62:630–649.

Severs et al. (2015). Smoking is associated with extra-intestinal manifestations in inflammatory bowel disease. J Crohn Colitis 10:455-61.

Ng S C et al. 2015. Environmental risk factors in inflammatory bowel disease: a population based case control study in Asia-Pacific. Gut 65(7): 1063-71.

Aujnarian A, Mack D R, & Benchimol E I. The role on the Environment in the Development of Pediatric Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Curr Gastroenerol Rep. 2013 May;15(326).

Parian, A., Limketkai, B., Koh, J., Brant, S. R., Bitton, A., Cho, J. H., ... Lazarev, M. (2016). Appendectomy does not decrease the risk of future colectomy in UC: Results from a large cohort and meta-analysis. Gut.

Nyobe Andersen et al., Gut 2016;in press

Garbenbroek et al. The ACCURE-trial: the effect of appendectomy on the clinical course of ulcerative colitis, a randomised international multicenter trial BMC Surg 2015;15:30

Okada, H., Kuhn, C., Feillet, H., & Bach, J. (2010). The ‘hygiene hypothesis’ for autoimmune and allergic diseases: An update. Clinical & Experimental Immunology, 160(1), 1-9.

Wine E. (2014). Should we be treating the bugs instead of cytokines and T-cells. Digestive Diseases 32(4): 403-9