Designing for Dignity: Rethinking Infrastructure for an Inclusive Society

By: Savoye’ M. Sharrieff

Imagine navigating a city where every public space is built for mobility and accessibility—yet remains inaccessible to over a quarter of the population living with disabilities. For too many, it’s like trying to find an iPhone charger in a room full of Android users. The challenges faced by disabled individuals reveal a gap in our infrastructure that engineering must address. Accidents and health issues can cause injuries or disabilities that prevent people from continuing life as usual. Therefore, the engineering field must adapt to accommodate not only the physically disabled but also those with mental disabilities. In this article, I aim to highlight some of the challenges and difficulties within this area of the engineering industry.

In the 1990s, President George H. W. Bush signed the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) into law. This act had a significant impact across many fields, but perhaps most profoundly on engineering. ADA guidelines promote inclusivity for individuals with disabilities in public spaces such as businesses, transportation, and other public accommodations. According to Hoffman and Johnson, “Creating accessible spaces is essential not only for equity but for the basic functioning of an inclusive society” (23). Now, civil engineers have a professional duty to implement ADA standards during the design process and act as allies for those with concerns regarding compliance. Sure, engineers follow ADA standards—just like some people consider making a peanut butter and jelly sandwich "cooking." We can all agree that there’s room for improvement.

The most visible group of disabled individuals are those with physical disabilities. According to the CDC, approximately “one in four U.S. adults—approximately 61 million Americans—live with a disability” (CDC). Whether they are deaf, blind, or mobility-impaired, changes need to be made to building designs to assist them at every opportunity. We have already implemented curb and sidewalk ramps, as well as braille signage, but these are seen as the bare minimum. Programs like New York City’s Accessible Pedestrian Signals (APS), which enable audible crossing signals for the visually impaired, demonstrate the need for engineering solutions beyond ADA’s foundational requirements. “While the ADA has laid the groundwork for accessible spaces, its basic standards have not kept pace with the demands for more sophisticated solutions” (Smith and Taylor 45). Accessibility for the disabled is not prioritized in technological advancements, even though disabled individuals make up about a quarter of the U.S. population. As engineers, we must devote more attention to this issue, or lives could be at risk due to our negligence.

Accommodating people with mental disabilities is often easier because many are fully or mostly capable of performing the same tasks as the average person. However, the less capable individuals are frequently overlooked, forced to remain indoors or restricted to simple tasks. For example, busy public spaces can be overwhelming for individuals with cognitive disabilities. Some cities and facilities are testing sensory-friendly environments—public areas that reduce overwhelming visual and auditory stimuli—enabling people with autism and other cognitive disabilities to feel more comfortable. According to Brown, “Public spaces that accommodate sensory needs, quiet areas, and clear signage are essential to creating an inclusive environment for individuals with cognitive disabilities” (89). It should be one of our goals to ensure that these individuals can enjoy outdoor activities and have experiences comparable to those of other people. In the future, technologies like self-driving vehicles could provide significant solutions to this issue, but they may not be enough to fully address the problem.

While some may argue that the costs of advanced accessibility measures are high, the benefits far outweigh these expenses when we consider the safety, inclusivity, and quality of life improvements for millions. Neglecting these issues could potentially lead to even more problems. For instance, in the event of an emergency in a tall building, a person in a wheelchair would have to either risk using the elevator or face the challenge of navigating the stairs, which would pose obvious difficulties. The potential dangers arising from ignoring this issue far outweigh the benefits of simple accommodations like handicap parking spaces.

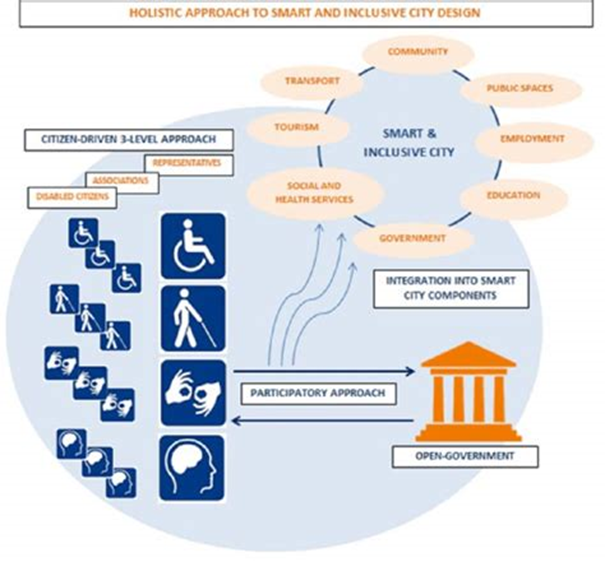

The engineering industry must come together not only to develop these solutions but also to implement them in our design plans, ensuring that individuals who face these challenges can maintain a stable life, regardless of their disabilities. As engineers and members of society, we are responsible for creating spaces that everyone can enjoy. By investing in accessible infrastructure and continuously advancing our approaches, we can ensure that no person is excluded from the world we build. “An inclusive society is one in which our infrastructure mirrors our commitment to equality and belonging” (Davis 102). Each of us has a role to play in advocating for accessibility—whether as engineers, policymakers, or community members. Together, we can build a world that truly reflects our shared commitment to inclusion and equity.

Works Cited:

Brown, Alex. Cognitive Accessibility in Public Spaces: Innovations and Challenges. Oxford University Press, 2021.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. “Disability Impacts All of Us.” CDC.gov, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 16 Sept. 2020, www.cdc.gov/ncbddd/disabilityandhealth/infographic-disability-impacts-all.html.

Davis, Patricia. Engineering Equality: Infrastructure and Inclusion in the 21st Century. Harvard University Press, 2018.

Hoffman, Miles, and Rita Johnson. Designing Accessibly: Engineering Solutions for an Inclusive Society. Cambridge University Press, 2019.

Smith, Laura, and George Taylor. Beyond the ADA: Advancing Accessibility in Modern Engineering. Routledge, 2017.