<iframe width="560" height="315" src="

Presently, two writers from Chile are Nobel Prize winners: Gabriela Mistral and Pablo Neruda. In addition to national prizes in literature, they received world recognition and achieved greater notoriety than traditionally-rooted artists such as Violeta Parra, renowned for collecting, researching and disseminating Chilean oral culture, who has not received much critical attention. Drawing from interdisciplinary research in the arts, this paper will attempt to give an aesthetic reading of Parra’s representation of indigenous issues in Chile. The first part of this paper presents a brief reference of today’s Mapuche conflict. The current state of this situation will also be tackled here and followed by a brief review of Parra’s engagement with the subject, as well as the artistic and historical influences of this female author. It will then move on to examine in some detail two visual works and a song in which Parra presents a counter-discourse. By breaking down and exposing musical and visual content, I will give important insights into how Latin American issues are depicted through the interplay of sounds, the correspondence of words and colours, showing us the small degree of which it has changed since then.

In 1982, English musician Robert Wyatt released a compilation album called “Nothing Can Stop Us”. Consisting primarily of cover versions of protest songs, it includes two Latin American songs “Guantanamera” and “Arauco”. The latter was released twenty years earlier from Violeta Parra's "Arauco tiene una pena”, in which the artist raises Mapuche's situation, one of the many issues present in Latin America today. The Mapuche are a group of indigenous inhabitants of south-central Chile and southwestern Argentina. Today the collective group makes up 80 per cent of the indigenous people in Chile, and about 10 per cent of the total Chilean population. When the British and American frontiersmen settled North America they forced the Cherokees, and the other Indian peoples into reservations where they still live today. But the situation in Latin America is different. The Spanish Conquistadors did not just kill the Indians and drive them from their homes. They also took the Indian women as wives and mistresses. For example, in Peru Pizarro took the wife of the Incan Indian leader.

Alonso de Ercilla. La Araucana (circa 1574)

Nowadays, Mapuche’s situation in Chile is still vulnerable. During the Pinochet dictatorship, all Mapuche land was privatised and to a large extent sold out to wealthy landlords and foreigners. Mapuches who move to the cities soon lose their culture in order to be able to get a place in the society. They face difficulties in getting jobs, education and are lower paid than their Chilean colleagues. In order to get a chance to climb the social ladder It is not an uncommon phenomenon to change a Mapuche name into a Chilean one, and avoid passing on the Mapudungun language on to the children. The previous governments in Chile have taken another standpoint towards the indigenous people. In 1993 the Indigenous Act, Ley Indígena, was introduced, which provides protection, promotion and development of the indigenous groups in Chile. If the Government or a company wants to move an indigenous from one place to another, they have to offer a piece of equal land. Nonetheless, some Mapuche have been prosecuted under counter-terrorism legislation when defending their land from the paper-pulp industry and the building of a hydroelectric Plant.

Mapuche Conflict pics

Pablo Picasso. Guernica (1937)

In this context, it is possible to recognise certain events that probably could have influenced Violeta Parra’s ideology and art to depict Mapuche’s issues. For example, Parra’s grandmother was a Mapuche. A second significant influence was Argentinean artist Atahualpa Yupanqui, who had started championing indigenous or native peasant culture in urbanised areas by creating songs and writing books about this subject. Furthermore, Parra probably became engaged with the notion of national and social struggles after the success of the revolutionary process in Cuba in 1939. Another feasible influence is “Guernica” by Picasso, painting created in 1937, which shows the tragedies of war and the suffering it inflicts upon individuals. This historical context was reinforced in 1940, when she met Mexicans David Alfaro Siqueiros and Xavier Guerrero, pioneers of the Mexican "muralism" movement in the early 20th century along with Diego Rivera. This movement with social and political messages sought reunify the country under the post Mexican Revolution government. Pablo Neruda led them to Chile in exile, where they worked on a mural called "Muerte al invasor" [Death to the invader] in a school donated by the Mexican government of Lazaro Cardenas after an earthquake in 1939.

David Alfaro Siqueiros. Muerte al Invasor (1942)

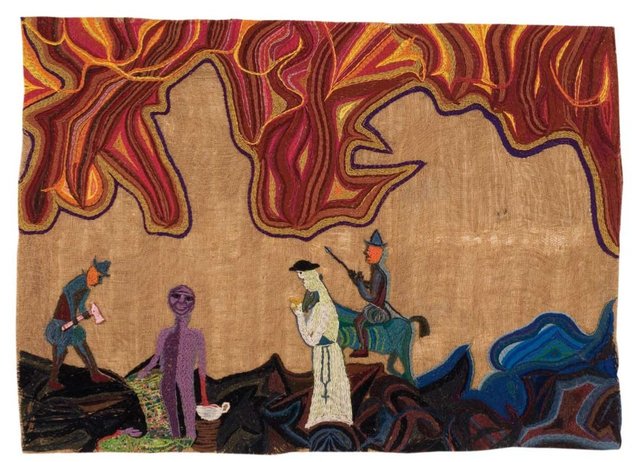

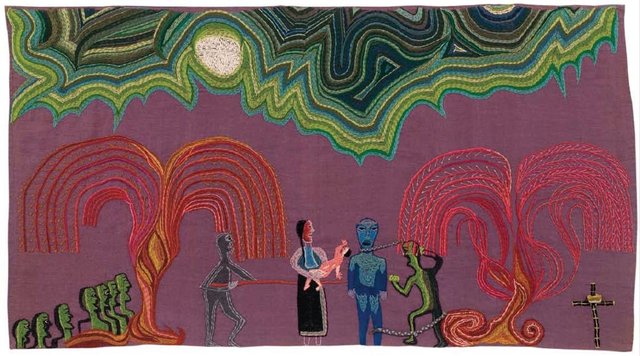

The indigenism or indigenous influence in Parra’s art is present and also translated across the different artistic genres of her artwork. Parra researched Chilean and Latin American folk culture before she began exploring the plastic arts and the incorporation of this expertise into her artwork allowed her to validate and regenerate traditions that she considered autochthonous. According to English scholar Lorna Dillon, this ideology is presented visually in embroideries like Los conquistadores and Fresia y Caupolican. The art of embroidery has been practiced for thousands of years. Some of the oldest embroideries in the world come from Latin America, specifically from the Paracas culture who were active in the south of Peru from 600 to 200 before Christ. Parra presents a polarised conception of history throughout her work, and Los conquistadores typifies this pattern with the colonised versus coloniser dynamic representing the poles of good and evil. In the 1960s indigenism was a broad cultural stratagem viewed by many artists and intellectuals as a means of reclaiming national identity. In the embroideries Los conquistadores and Fresia y Caupolicán Parra presents emblematic tales from the collective Chilean imaginary using an indigenism that counteracts the indianism of colonial discourse. These powerful embroideries can essentially be read much like stories, indeed they are based on tales from La Araucana or The Araucaniad, as it is known in English, the national heroic tale of Chile and one of the most important works of the Spanish Golden Age.

Violeta Parra. Los Conquistadores (1964)

Los conquistadores and Fresia y Caupolicán are not only visual translations of oral narratives, which depict scenes from the Chilean collective imaginary, but also, they discredit the pejorative notions of indianism by depicting the barbaric acts of the colonisers and reiterating tales of the heroic Araucan warriors. This is a potent counter-discourse, since the cult of the hero in Chile tended to focus on military figures and there was an inherent racism in the army which meant that citizens from ethnic groups tended to be excluded.

Violeta Parra. Fresia y Caupolican (1965)

Furthermore, they contain an implicit condemnation of the role of the church in the conquest. For example, the inclusion of the priest in Los conquistadores is in line with popular narratives where religion played a central role. The priest also serves as a reminder that religion was crucial to the success of the colonial project and that there was an ecclesiastic justification for the devastation of existing cultures. In Fresia y Caupolicán like Los conquistadores the elements included in the embroidery are not intended to depict the scene as it would have occurred but to represent certain ideas. The inclusion of a crucifix in the far right of the Fresia y Caupolicán, like the inclusion of the priest in Los conquistadores, is a reminder of the reprehensible role of the Church in the conquest of the Americas. Parra has further highlighted the link between the church and the state by attaching a knitted crown to the cross.

Parra’s condemnation of Christianity also extended to the modern era, but it was deeply rooted in her interpretation of the machinations of the church in the colonial period. By aligning the priest with the soldiers as they savagely mutilate Galvarino, which acts as a metaphor for the devastation wrought on Latin America by the Spaniards. Parra invokes Araucans warriors in her song ‘Arauco tiene una pena’, a protest song that can be read as a call to arms. In a style that typifies art dedicated to Latin America of the mid-twentieth century, here Parra calls for an uprising. The lyrics refer to 'el alma de Galvarino' (Galvarino’s soul) and 'la voz de Caupolicán' (Caupolican’s voice) structuring these two warriors as personifications of the nation. This idea is visually presented in Parra's plastic art by depicting scenes that include the warriors and thus I interpret the scenes Los conquistadores and Fresia y Caupolicán as visually translating the song ‘Aruaco tiene una pena’. The embroidery Los conquistadores celebrates Galvarino, one of the Chilean emblems of national identity.

<iframe width="560" height="315" src="

Parra’s engagement with indigenism is clearest in her own writing, particularly in ‘Arauco tiene una pena’. Although Parra’s repertoire does not show a systematic use of Mapuche music, it does use indigenous elements which structure and frame a particular aesthetic outcome. Musicological research have found that, overall, Mapuche’s music uses five musical notes only: C,D,E,F and G, which could lead us to think it as a type of "pentatonic music". Arauco tiene una pena presents a particularity within the Chilean traditional music, because it shows tonal and modal musical features. The difference between modal and tonal are within the harmonic languages surrounding the tonal center. Tonality implies the system of common-practice harmony well-established by the eighteenth century that uses major and minor keys. On the other hand Modal music uses diatonic scales that are not necessarily major or minor and does not use functional harmony as we understand it within tonality. The term modal in music is most often associated with the eight church modes.

Arauco tiene una pena's mixolydian mode.

It can be seen two kind of modal treatment in Arauco tiene una pena. Parra uses the Mixolydian mode, either completely or partially in Arauco in Arauco tiene una pena, and it can be due to the traditional melodic tritone used to in some Mapuche songs. It can be seen in the first two octosyllabic lines of the stanza as it is played by using a major chord with the seventh minor note. The song is in E major key, and uses D major, G major and B major chords. but D and G major don’t correspond to E major key. Why is she using D and G major chords? This can be explained by the musical term "modal interchange". To put it simply, modal interchange is the practice of temporarily borrowing chords from a parallel tonality/modality without abandoning the established key. An example of modal interchange is C Major and A Natural minor that share the exact set of notes. In the same fashion, G mayor and D major are not part of E Major key and this reveals that the modal interchange chord has been borrowed from the Aeolian parallel minor. To sum up, it can be argued that Parra confronts and mixes the tonal and modal harmony in this song, which firstly reveals the significance of Mapuche traditional tunes by claiming its aesthetic features. And secondly, conveying this tonal and modal conflict as a musical confrontation, because it can be thought of as depicting the Mapuche resistance to Spaniard and Chilean domination.

In this paper, I put forward the claim that Parra created activist art that addressed socio-political issues and how they are articulated and translated across the different mediums in which Parra worked. Unfortunately, this activist’s art is still relevant in today’s Latin America. In 1964, when Parra became the first Latin American artist to hold a solo exhibition in the Louvre museum, these embroideries and songs were an important part of this display. Also, the world’s most renowned cultural organisation validates Parra’s visual language as an artist of global stature who made a strong contribution to Latin American art. Likewise, this is it also recognition of those people who has been researching, promoting and collecting Latin American roots.