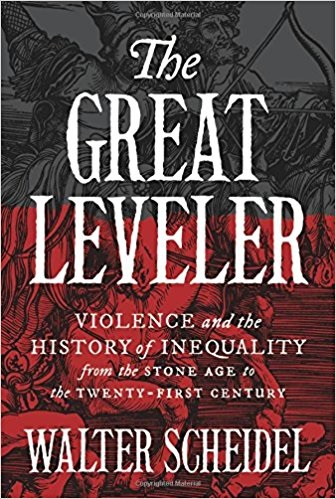

This report by MCT International offers a very interesting review of an important book by Princeton University entitled "The Great Equator: Violence and the History of Inequality from Stone Ages to the 21st Century".

Text of the report

World War II destroyed the economic infrastructure of Germany and Japan . And brought their factories in the ground, and made the yards of the railways to them and destroyed their ports. But in the decades that followed, something puzzling happened: the economies of Germany and Japan grew faster than the economies of the United States , the United Kingdom and France . Did not the defeated over Almzfar victory?

In his book Rise and Fall of Nations in 1982, economist Mancour Olson responded to this question by arguing that instead of hampering Axis economies, catastrophic defeat had already benefited from them by opening up competition and innovation. As noted, the war in Germany and Japan destroyed special interest groups, including economic cartels, trade unions and professional associations. German party trade unions and Japanese-controlled conglomerates have died, as are American truck drivers, the UK Engineers Association and the French Federation of Building Industries.

After a generation of war, only a quarter of the professional associations in West Germany were back to the pre-war era, while half of the UK unions returned. In Olson's results, however, the consequences are worrisome: in politically stable countries, narrow alliances of business lobbies impede economic growth through self-interest policies, and only a military defeat or a horrific revolution that can overcome its shortcomings.

During Olson's writing, few economists were concerned about economic inequality in developed countries. Unemployment and sluggish investment were the problems at the time. As experts focused on inequality within countries, they did so with respect to late manufacturers, with migration from poor villages to richer cities highlighting income disparities. Yet even there, inequality was one of the temporary side effects of development. Economist Simon Kuznets argued that it had dissipated with modernization.

If Olson had taken the inequality into consideration, he might have noticed that World War II had other strange economic consequences. First, destruction has reduced inequality - not only in defeated countries, but also in triumphant countries, even in neutral countries. Secondly, these cuts proved to be temporary. In the 1970s, advanced economies began to become less common, challenging the famous Kuznets hypothesis.

These puzzles lie at the heart of The Great Leveler, an impressive new book by Walter Schiddell. Schindel suggests that since the search for food has paved the way for agriculture, high and growing inequalities have been the norm in politically stable and economically viable countries. The only thing that reduced it, as Schiedel argues, was a kind of violent shock - a major conflict like World War II, a revolution, a state collapse, or a pandemic. After every such shock, "the gap between those who own and who have not, and sometimes very much" is narrowing. Unfortunately, the short-term impact has been steadily going on, and the restoration of stability has begun in a new era of increasing inequality.

Today, the risk of violent trauma is greatly reduced. Nuclear deterrence has produced an unimaginable super-war, and the decline of communism has made revolutions gripping wealth unthinkable. Strong government institutions have avoided the danger of state collapse in the developed world and modern medicine between the epidemic . However, such changes, he says, may be "very skeptical" about the feasibility of a future settlement. Indeed, he expects economic inequality to continue to rise in the foreseeable future.

The book "The Great Equalizer" should launch high-pitched alarm bells. Schiedel's appeal in his call to the world's elite to find ways to equalize opportunities, do so before the driverless cars, automated stores, and other technological advances that hold the job. Its bloody history suggests that reducing inequality will be difficult, even in the best of circumstances. But he also exaggerates his case; there are reasons to believe that societies can reform without catastrophic disasters.

The march of inequality

Beyond the ages and civilizations, the book "The Great Equator" finds an example after an example of periods of rising inequality interspersed with catastrophic events that suddenly crushed the distribution of income and wealth. The collection of evidence is very exciting. Schiedel traces the distribution of wealth between 6000 BC and 4000 BC through physical well-being indicators, such as skeletal height and tooth lesion; obvious consumption signs , such as lavish burial; and evidences of solid hierarchy, such as temples.

Inequality in the Roman Empire is estimated by examining the assets of senior officials and influential families, as reported in the censuses. It measures Ottoman inequality by shifting to the records of real estate settlements and expropriations. As for ChinaPre-modernity, the fluctuations over time in the number of engravings of shrines, which only the rich can estimate, are responsible for the mobile densities of wealth. There is no doubt that specialists in certain ages and regions will face some of the assumptions of Schiddel and his reasoning and perceptions. But no discreet reader will fail to believe that inequality has diminished and vanished through space-time.

Schiedel also seeks to explain the causes of inequality. Thomas Beckett, in his best-selling book Capital in the 21st Century, answered this question by arguing that the rate of return on investment generally exceeds the rate of economic growth, making capitalists richer than any other person. Sheidel accepts this mechanism, but adds other mechanisms. Perhaps the simplest mechanism involves ferocity and predation. Until recently, the only way to become rich was to prey on the fruits of others' work. The Fascists seized power, and wealth was accumulated through taxation, land confiscation, enslavement and conquest. They also monopolized lucrative economic sectors, in favor of themselves, their families and their friends to a large extent. The exercise and maintenance of all this power requires the maintenance of a military capability capable of crushing the United Nations, which in itself has served as a tool for further militancy and ferocity. In Rome"The leaders had full power over the spoils of war, and they had to decide how to divide them between their soldiers, their officers and their assistants, who were drawn from the elite, the state treasury, and themselves."

In the modern world, too, the authoritarian states maintain their ruling power over political power, acquire enormous wealth through violence, and look to China, Egypt, Russia and Saudi Arabia. As these countries differ from pre-modern countries, they share power with giant private corporations. China did not have pre-modernity for the electronic commerce company "Ali Baba", nor had pre-modern Egypt anything equivalent to Bank of Alexandria, one of the largest financial institutions in the country. Their owners include billionaires who have become wealthy without reliance on violence (or, at the very least, without relying directly on violence, because they may indirectly support it by paying taxes to repressive countries).

Giant corporations also play huge roles in advanced democracies. In these countries, the army and police are forced by various institutions, and politicians must maintain popular support for remaining in power. But the only thing is that citizens have the right to remove corrupt administration and other entitlements that enable them to exercise this right. The American tax system has many loopholes that benefit 0.1% of the two rich Americans, but the other 99.9%, through their options at the ballot boxes, actually allowed these privileges to continue. In recognition of this strangeness, Schiddel points out that voters act against their own interests because of the power of elites. Thus, inequality continues to rise - even so, when a shock is reduced.

Inequality is sporadic

World War II has essentially reduced inequality by obliterating assets unequal to the rich, such as factories and offices. As Schiddel notes, a quarter of Japan's physical capital was wiped out during the war, including four fifths of all its merchant ships and up to half of its chemical plants. Although France was a triumphant side, two-thirds of its capital evaporated. The war has also led to a decline in financial assets such as equities and bonds, and the value of the remaining leased properties has been reduced almost everywhere. In both victorious and defeated countries, the rich have lost a larger share of their wealth than the rest of the population.

However, this is not just destruction that reduces inequality; the inflated taxes imposed by governments to finance the war effort have also helped. For example, in the United States, the highest income tax rate was 94% during the war, and the property tax rate rose to 77%. As a result, net income for the top of 1% of earnings fell by a quarter, even as low wages rose.

Collective community mobilization operations necessitated by war also played a crucial role. About a quarter of Japan's male population served in the military during the conflict, and although the share was lower in most other countries, the number of enlisted men was not as small as historical standards. During and after the war, veterans and their families formed pre-arranged circles that felt they had the right to share in the wealth created by reconstruction. In the United States, the Supreme Court did not end the White House primaries only in 1944, no doubt partly because of the shift in public opinion against the exclusion of African Americans who took part in the wartime sacrifices. France, Italy and Japan adopted the right to vote between 1944 and 1946. The war effort has also stimulated the formation of trade unions that have been plagued by increasing inequality by giving workers the ability to bargain collectively and pressure governments to adopt pro-worker policies.

With this logic, modern warfare by professional soldiers is unlikely to have the same effect. Look at the wars in Afghanistan and Iraq: Although some of the veterans of these conflicts have suffered exhaustion, they have formed a very small circle to gain skillful attention, and few Americans feel obliged to support large transfers of wealth to voluntarily recruited citizens .

Revolutions, explains the Great Book of Masons, play a role as much as wars when it comes to redistribution: it rewards access to resources only as much as violence. The communist revolts that rocked Russia in 1917 and China from 1945 were very bloody. Within a few years, the private property revolutionaries abolished the land, nationalized almost all the works, and destroyed the elite with mass deportations, imprisonment and execution.

As well as all of this fundamentally destroyed wealth. The same could not be said of bloody revolutions that had far less economic consequences. For example, although the Mexican Revolution, which began in 1910, led to the reallocation of some land, this process spread over six decades, and the land distributed in general was poor quality. The rebels were not too violent to destroy the elite, which quickly reorganized themselves and managed to slow down the reforms that ensued. Schindel concludes that in the absence of mass violence, which is concentrated in a short period of time, it is impossible to redistribute wealth effectively or achieve economic equality of opportunity.

Indeed, Schiedel questions the existence of progressive, consensual and peaceful paths to greater equality. One can imagine that education reduces inequality by giving the poor an opportunity to go beyond their parents' situation. However, in post-industrial economies, elite schools serve the children of unequally privileged parents, as the assortative mating - the tendency of people to marry their social and economic peers - increases the inequality that ensues. Similarly, one can expect financial crises to act as another brake on the concentration of wealth, because they usually afflict the rich in obscurity. But these crises tend to have only temporary impact on elite wealth. The collapse of the stock market in 1929, which has always destroyed innumerable huge fortunes, is an exception to the rule.

He argues that the democratic process is unreliable to reduce inequality. Even in countries with free and fair elections, the formation of practical alliances that support redistribution is rare. Indeed, the poor generally fail to circumvent leaders who pursue egalitarian policies. Schiddel does not go into much detail about the cause, but the problem is largely the problem of coordination. According to the theory of collective action (which Olson won popularly): the larger the coalition, the harder it is. This means that given the figures alone, 50% will always have difficulty packing around a common goal than if the mobilization was 0.1%. Not only are incentives for progress larger in large groups; in addition, priorities within them can be more diverse.

Another obstacle to reform lies in efforts to impede mobilization and mobilization. Throughout the world, elites have promoted ideologies that focus the poor on non-economic axes, such as culture, ethnicity and religion. It also publishes conspiracy theories that attribute chronic inequality to bad guys, real or imagined. Today's populist politicians - whether right or left - are demonizing certain groups, distracting attention from the true origins of economic inequality. As for US President Donald Trump and Frenchman Marie Le Pen, those sources are immigrants; for US Senator Bernie Sanders and Frenchman Jean-Luc Melenschon, they are companies. Even elites who deny populism distract attention from real problems. For example, many American academics advocate positive discrimination, which tends to favor the richest minority, and has no real impact on inequality.

Equality in peace?

But Schiddel's own narrative also offers a reason for hope: as the Great Book of Mowawati acknowledges, some countries have found ways to reduce inequality without catastrophe. In the 1950s, Schiedel notes, South Korea has redistributed land to pacify its peasants and discourage them from alliance with communist North Korea. During the same period, Taiwan, which fears the invasion of mainland China, has made similar reforms to strengthen domestic support. Thus, both places were able to promote equality peacefully, in order to prevent violence that would have been more costly to the elites. Schiedel explains these cases by pointing out that World War II and the Korean War have enabled the masses and reduced the elites. But he also notes that the Mesopotamian rulers of 2,400 BC to 1600 BC tempered, repeatedly, the debt to face the possible shake-up.

Schiddel also mentioned a useful case for the Ottoman Empire. From the 14th century onwards, the Ottoman sultans systematically confiscated their subjects, including merchants, soldiers and state officials. At the height of the empire, in the sixteenth century, the abolition of this privilege was inconceivable. But from the late 18th century, the economic, technological and military rise of Europe led the Sultanate to worry that keeping this privilege would hinder economic growth, encourage secession, and set the stage for foreign occupation. Thus, in 1839, Sultan Abdul Majeed peacefully handed over this privilege, in addition to many of the Ottoman elites that had enjoyed it for centuries. A few years later, he reformed the judicial system, creating secular courts available to people of all faiths as an alternative to Islamic courts, which, because of discrimination against the public and non-Muslims, contributed to the promotion of inequality for a long time.

In all these cases, the beneficiaries of the established privileges, recognizing the existential threat looming, have chosen to choose reforms. Today's populist wave is not yet a serious threat to the rich. But if Schiedel's speculation echoes the ever-growing inequality, that may change. This trigger can, for example, come from the seizure by radical advocates of redistribution in some G-7 countries. At that stage, elites may form political alliances to pursue top-down reforms that are now hopelessly unrealistic. In times of peace and stability, as Olson recognized in his book Rise and Fall of Nations, elites form alliances to serve themselves to increase their wealth. Faced with the possibility of losing everything, they may do the same to avoid a more radical redistribution.

A s with any collective action, the utilization process can fall into straits. Some wealthy individuals may choose to allow other elites to shoulder the burden of reducing inequality, such as financing a new alliance between the two parties. If there are enough beneficiaries, the overall effort will fail. However, the nature of increasing inequality will reduce disincentives: the more concentrated the wealth is on the elite, the fewer people must be organized to form a movement committed to reducing inequality. In the United States today, there are just over 100 billionaires - people with a net worth of 11; and if only half of them form a political bloc aimed at raising property taxes to equalize educational opportunities, the effort is likely to attract attention.

Another reason to reduce pessimism is that it relates to the comparative characteristics of different types of inequality. The great monastic book focuses on inequality within States, without paying much attention to equality among States. But the latter have become increasingly relevant to human happiness. Just as mass transit makes national disparities important for those whose frame of reference has previously been restricted to their communities, the Internet increases the importance of international disparities. Which means much more to Chinese today and to Egyptians and Mexicans than to their grandparents that they were generally poorer than Americans. The technologies that allow people in the developing world to communicate more with people in the developed world - from video chat to universities online - promise that these global differences are more important, reducing the importance of national inequality that focuses on Sheidel.

Finally, the good news is that global inequality has declined significantly since the Second World War, even as incomes and wealth have been concentrated in major countries. As the economically underdeveloped countries grow faster than the developed countries - which is largely due to the reduction of trade barriers in the developed world - gaps have been bridged among people in different countries. In late 1975, half of the planet's population lived below the current $ 1.90 a day poverty line, which the World Bank considers extremely poor. This percentage has now fallen to 10%. Countries that have entered the early stages of manufacturing only a few decades ago, from India and Malaysia to Chile and Mexico, now export high-tech goods. These huge and rapid transformations achieved in a remarkable peaceful era provide hope for those who have ended the great book of reconciliation with great despair.