Since the beginning of the Euromaidan protests in Ukraine in late 2013, much has been written about the disinformation campaign launched by Russia, first to discredit the Ukrainian revolution and then to justify the annexation of the Crimea in March 2014 and hide a direct military invasion of Russia from eastern Ukraine that produced the Russian-Ukrainian War which is full, but still not recognized. 1

In many cases, the Ukrainian-centric disinformation campaign is correctly identified as part of the wider Russian information war against the West. It started long before developments in Ukraine and the Russian-Ukrainian War, but, as Anne Applebaum said in March 2014, the information war is now "being done on an unprecedented scale". 2 Despite this and similar warnings, as well as analytical reports, the West 3 has done little so far to stand for the Russian information war. Tellingly, more than a year after the Crimean annexation, The Economist noted that Europe was "late to wake up to the Russian information war", 4 but this is very different from the actual resurrection.

Meeting on 19-20 March 2015, the Council of Europe adopted a conclusion featuring, in particular, the so-called "first step" in the EU's prospective response to the Russian information war: "The Council of Europe stressed the need to challenge Russia's ongoing and inviting disinformation campaign The High Representative, in collaboration with Member States and EU institutions, to prepare in June [2015] an action plan on strategic communications. "5 While this initiative can not be denied, it is unclear whether EU member states will be able to consider this with proper seriousness.Among other things, one can hardly deny that countries like Spain or Portugal are much less concerned about the information war Russia than the Baltic or Polish countries.

This article discusses the nature and forms of information on Russian warfare, and discusses how the West might challenge it.

Purple Russian hybrid information

The concept of information warfare originated from the US Department of Defense's (DOD Directive TS-3600.1) secret directive adopted in 1992, in which the term implies its dual nature, defense and offensive. In purely military terms, as described by the Department of Defense in 1995, information warfare is understood as "actions taken to maintain the integrity of the information system itself from exploitation, corruption, or harassment, while at the same time exploiting, destroying or destroying information systems enemies and in the process of achieving information advantage in the application of force ".6

Writing in 1994, Winn Schwartau argues that the idea of kinetic weapons, such as bullets or bombs, should be excluded from the concept of real information warfare. 7 This exclusion adds an important aspect to the nature of this type of warfare: this is information, not anything else, used to attack enemy information systems.

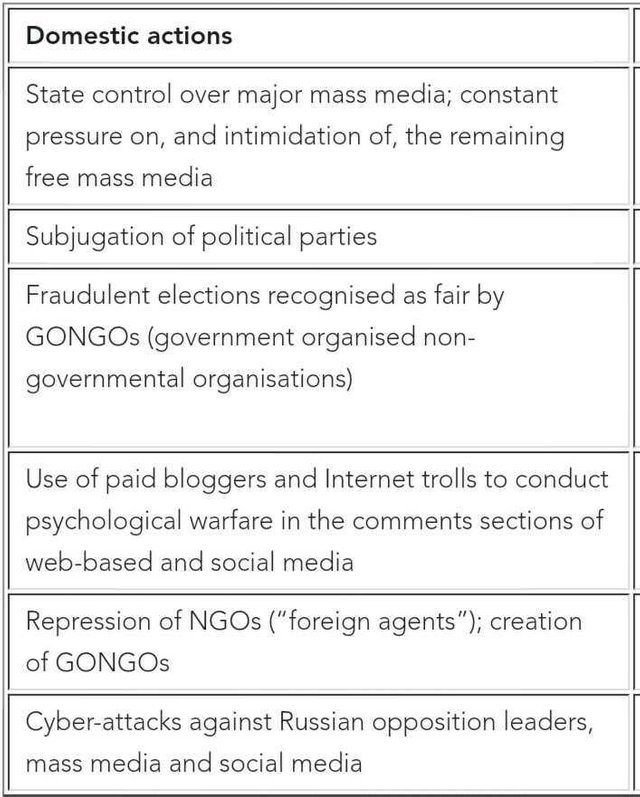

As in every other country, the information system in Russia is a complex of resources, people, technologies, methods, and processes of collecting, processing, producing, and presenting information. President Vladimir Putin began creating the current information system during his first presidential term (2000-4). During this period, not only did he destroy the unfaithful oligarchs like Mikhail Khodorkovsky, Boris Berezovsky and Vladimir Gusinsky, but he also gradually restored state control over the mainstream media, especially the TV channels previously controlled by the disloyal oligarchy, and began to subdue only a small amount of mass media remained in the interest of his rising authoritarian kleptocratic regime. 8

State control over major TV channels is an important foundation of Russia's contemporary information system. However, products from the mass media are only one element of the system, which also includes information products from all actors and institutions involved in collecting or communicating information, such as NGOs, civil society, religious organizations and political parties, and components of the repressive apparatus (army, police , judiciary and prison systems) that provide intelligence regimes.

Along with the repressive apparatus, the purpose of Russia's Putin information system is to protect it from competing models of political, economic, cultural and social development. It is for this reason that mass media, NGOs, civil society, religious organizations and political parties can freely operate in Russia only if they, at least, remain true to the regime.

Putin put forward the threat felt to Islamism as a potential development model in certain areas of Russia in the early 2000s, to consolidate his government. However, this has never been an attractive model for Russia as a whole, and the single most convincing development model and, ultimately, more convincing is Western liberal democracy, which is incompatible with the Putin regime.

In peacetime, an information system in any country reproduces itself, while the "hard element" of the repressive apparatus gathers intelligence on internal and external enemies perceived. The crucial difference between information systems in Western liberal democracies and in Russia Putin is that the Russian version has been increasingly functioning, since Putin's first term as president, in a manner that implies conflict.

Indeed, while strengthening authoritarian kleptocracy, the Putin regime is constantly concerned about Russian information systems with references to perceived threats. These include Islamic terrorists in Chechnya and Dagestan, an allegedly disrespectful attitude from the Estonian authorities against the Soviet monuments in Tallinn, the "color revolution" in Georgia, Ukraine and Kyrgyzstan, the potential challenge of the "color revolution" in Russia, the Georgian invasion, protests by the opposition political ("fifth columnist") and, finally, the Ukrainian revolution. Despite the diversity of these alleged threats to the Putin regime, the Kremlin believes that Russia is attacked from an enemy - the West - behind them all.

The Russian information system has not been fully armed in recent months, and its external repressive apparatus - the army - is not deployed on a full scale. Russia Putin does not wage a massive information war in the West. It would imply a total denial of access to information about developments in Russia, isolation of Russian public information, blocking or disrupting access to enemy command-and-control capabilities, cyber attacks aimed at destroying enemy networks in politics, military and economic fields, psychological operations strong and sustainable (misinformation and propaganda), etc.

It is difficult to measure the success of the Russian hybrid information warfare in the West, because we do not always know the short-term and long-term goals.

On the one hand, in Russia itself, the success of Kremlin propaganda is not ambiguous. According to a poll by the Levada Center in January 2015, the number of Russians who have negative attitudes toward the US rose from 44% in January 2014 to 81% in January 2015. The corresponding figures for the EU are 34% and 71%, and for Ukraine 26% and 64%. 9 It is easy to measure the success of Kremlin propaganda in Russia because the goal is clear: to secure existing information systems and, therefore, to consolidate the regime. In addition, short-term and long-term goals coincide in this case.

On the other hand, long-term goals, at least, hybrid information warfare in the West is not clear. It makes sense to assume that the culmination of home kleptocracy is the Kremlin's long-term goal in international relations as well. The problem is the Kremlin believes in the alleged Western attack on Russia. Thus, to defend the regime, the Kremlin will - like its cynical and aggressive behavior in recent years - continue to "dismantle the West", 10 that is trying to minimize the US role in global politics, weakening transatlantic relations, undermining NATO and destroying the EU. But we can only speculate on the extent to which the Kremlin is willing to neutralize the perceived threat on the way to unifying Putin's regime.

Take the challenge

Yet it is not clear the precise nature of the Kremlin's long-term goal with regard to hybrid information warfare in the West, three clear points:

1.Russian information system Putin is mobilized so far as to engage in a hybrid information warfare against the West, which he considers to be at odds with Russia.

2.The Russian hybrid information warfare is aggressive and aims to divide and subvert the West; because it poses a clear risk to the national security of Western countries, especially those geographically close to Russia.

3.Russian ethnic and Russian speakers living in Western countries are more receptive than other citizens for Russian hybrid war information. 11 In addition, Russia considers ethnic Russians and Russian speakers as "peers", while hybrid information warfare aims to divert their allegiance - a process that contributes to political and socio-cultural tensions.

Given these challenges, it seems appropriate that the West should accept Russia's hybrid information warfare challenge, and the Council of Europe's decision to finally solve the problem is a step in the right direction. The recommendations produced by Peter Pomerantsev and Michael Weiss can be recommended as guidance in this process. 12

One of the most discussed initiatives that can help the hybrid information war in Western Russia is the creation of Russian-language TV channels based in the European Union. EU Member States have offered three different visions in this regard: the creation of national TV channels aimed at their own Russian speaking audiences; pan-Baltic TV channels; and Russian-language TV channels to be broadcasted to Russian territory.

The most rational choice seems to be the combination of the first and third vision: Russian-language broadcast TV channel to Russia but with slots available for national coverage and special programs. The length of this national slot will depend on the significance or size of the Russian-speaking community in certain Western countries. Conceptually, they will highlight and focus on the successful integration of ethnic Russians into their chosen Western society, thereby harmonizing their political allegiance.

At the same time, the departure of a narrow national approach in this context would allow funding for such TV channels to be sought not only from national agencies and EU-based structures but also from US and Western-based organizations in general. Penetration of information in Russian territory is very important and the West should be interested in changing the information systems that Putin makes in Russia. After all, the suppression of the free media remains the basis of its authoritarian kleptocracy. Broadcasting of RTs in the West by Russia should have a major impact on the unwillingness of the Russian government to allow broadcast of Western Russian TV channels. West will benefit from such TV channels,

1.About the developments in Ukraine, see Andrew Wilson, Ukraine Crisis: What does that mean for the West (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2014).

2.Anne Applebaum, "Russian Information Fighters Exist in March - We Must Respond", The Telegraph, March 7, 2014, http://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/worldnews/europe/russia/10683298/Russias-information-reader-is-on-march-we-must-respond.html.

3.See, for example, Peter Pomerantsev and Michael Weiss, The Menace of Unreality: How the Kremlin Completes Information, Culture, and Money (New York: Institute of Modern Russia, 2014), http://www.interpretermag.com/wp-contents/uploads/2014/11/The_Menace_of_Unreality_Final.pdf.

4."Armada Aux, journalist!", The Economist, March 21, 2015, http://www.economist.com/news/europe/21646756-europe-belatedly-waking-up-russias-information-warfare-aux-armes-journalists.

5."Meeting of the Council of Europe (19 and 20 March 2015) - Conclusion", Council of Europe, March 20, 2015, http://www.consilium.europa.eu/en/meetings/european-council/2015/03/european-council-conclusions-march-2015-en_pdf/.

6.Quoted in Edward Waltz, Information War: Principles and Operations (Boston: Artech House, 1998), p. 20.

7.Winn Schwartau, Information War: Cyberterrorism: Protecting Your Personal Security in the Electronic Age (New York: Thunder's Mouth Press, 1994).

8.On the nature of the Putin regime, see Karen Dawisha, Putin's Kleptocracy: Who Owns Russia? (New York: Simon & Schuster, 2014).

9."Mezhdunarodnye otnosheniya", Levada- Tsentr, February 9, 2015, http://www.levada.ru/09-02-2015/mezhdunarodnye-otnosheniya.

10.Janusz Bugajski, Uncovering the West: Russia's Atlantic Agenda (Washington: Potomac Books, 2009).

11.See, for example, Current Events and Different Information Sources (Tallinn: Saar Poll, 2014), http://oef.org.ee/fileadmin/user_upload/Current_events_and_different_sources_of_information_ED__1_.pdf).

12.Pomerantsev and Weiss, The Menace of Unreality, p. 40-3.

Curated for #informationwar (by @truthforce)

Downvoting a post can decrease pending rewards and make it less visible. Common reasons:

Submit

Aku sangat menyukai postingan kamu... karya tulis yang bagus

Downvoting a post can decrease pending rewards and make it less visible. Common reasons:

Submit

Good post...saya sangat suka dengan post ini

Downvoting a post can decrease pending rewards and make it less visible. Common reasons:

Submit

Posting yang sangat bagus...

Ini pantas dihargai oleh @informationwar

Downvoting a post can decrease pending rewards and make it less visible. Common reasons:

Submit

A truth about propaganda is it is a war on truth. No government can exist in a world where the truth is known. Thus they meaning the criminal cartels known as governments or the agencies must spend most of the resources they steel from the people in warping the perception. Thus the information war is a war on the truth. Nice article.

Downvoting a post can decrease pending rewards and make it less visible. Common reasons:

Submit

Thanks you bro for comentar

Downvoting a post can decrease pending rewards and make it less visible. Common reasons:

Submit

Removed vote because of plagiarism.

Downvoting a post can decrease pending rewards and make it less visible. Common reasons:

Submit