Making money is the goal of everyone in the stock market (or crypto) from the most novice retail investor to the seasoned fund manager. Unfortunately, the majority of people who try their hand in the market will lose money. Even among the small percentile who end up net positive, only a small elite group has demonstrated the ability to beat the market with consistency over time.

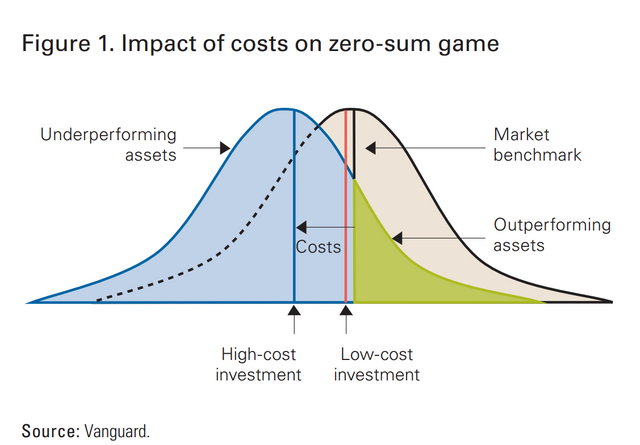

If you ask John Bogle, the creator of the Vanguard Market Index fund in 1975, he will tell you that trying to beat the market is a fool’s game. Since the start of his fund, it has outperformed 99.2% of all other funds. Of the 335 funds at that time, only 3 have managed to outperform the Vanguard Fund and he anticipates this will fall to 0 in the years to come. His low cost structure is perfect for capitalizing on the natural growth of the market without wasting any time stock picking or assuming unnecessary risk. From his perspective, the market will return 100% of the profits made publicly every year and those profits should be distributed directly to its shareholders. When you involve funds, experts, and traders that try to beat the market however, the total return of the market remains the same, yet the return to investors decreases. The addition of fees, taxes, cash drag, and commissions in the financial sector cuts deeply into profits.

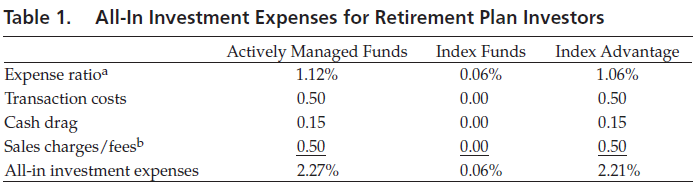

As you can see from the chart below, the average actively managed fund will have to remove 2.27% of their returns to cover costs before they make their way back to the investors. So they are operating with a handicap out of the gate and even if their fund says it beat the market for the year, by the time the returns trickle back to investors they will usually find themselves underperforming the market.

It is always important to remember that your return is the amount that ends up back in your wallet. People play games when it comes to expressing returns. Very clearly, your percentage return is (the amount you ended with - the amount you started with) / (the amount you started with). That’s it! If you are receiving a different amount, that isn’t your return.

“In the short term the impact of costs may appear modest, but over the long run, investment costs become immensely damaging to an investor’s standard of living. Think long term!” – John Bogle

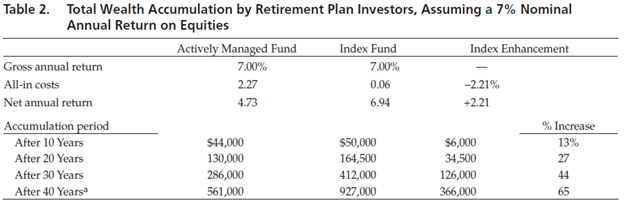

The magic of compounding returns is what Warren Buffett often attributes his vast fortune to, though it can also work against you. While a 2% decrease in return does not seem so significant at first, over the course of a lifetime it can really add up. In the chart below you can see that a “small” 2% difference attributed to actively managed fund expenses accounts for a $366,000 gap in performance compounded over the course of a 40 year $10,000 principal investment. Not so small anymore. The difference is only more staggering the higher your principle in year one is.

A large part of why these costs are so high is that portfolio turnover has increased from 30% in the 1960s to 140% today. That means in the 60s portfolio managers would hold their stocks for roughly 3 years. Today, the hold time is much shorter as fund managers buy and sell their entire portfolio in less than a year on average. This is important for a number of reasons. First, if your portfolio is being turned over frequently then you are entering and exiting most of your positions more than once. With every move, commissions and normal trading expenses are racked up decreasing returns. Next, the tax on gains made on investments held for less than a year is much higher than a gain made on a long term investment. Sometimes this divide can be as large as 40% compared to 15% respectively, depending on your situation. If you hold the investment for several years, you can watch your money compound many times before paying any taxes at all.

“I found that the entire fund industry worked a certain way, and that their results reflected the mediocre way in which they operated.”

– Mohnish Pabrai, recalling an important discovery he made at the outset of his investment career

So there are obviously many drawbacks to having a high turnover portfolio, though that’s not to say that you can’t succeed with a high turnover strategy. High turnover allows some investors to attain exponential growth by reinvesting and compounding returns within a single year as opposed to waiting years for capital to compound within a single company. Even Warren Buffett had high turnover in the early days with his “cigar butt” value companies. The right strategy often depend on the situation and the individual. To Bogle’s point though, the factors that come with high turnover do put funds at a distinct disadvantage to the market’s performance over time. Though this can pale in comparison to the the pitfalls facing the average fund investors.

If you were an investor dissatisfied with the performance of your fund, what would you do? The obvious solution would be to seek out the best performing funds over the past couple of years and move your capital there. This decision is a paradox, however, as it is both the most logical thing to do and also the most nonsensical due to the situation it creates. Historically you will not be the only dissatisfied investor in the market moving your capital to the best performing funds, all of the other dissatisfied investors are doing the same thing. The result is the best funds will have a huge influx of capital that must be allocated into investments. The trouble is that the investments the funds had previously made to attain those high returns are probably not a great value anymore, meaning the buying opportunity is no longer favorable. But they also cannot just leave this cash floating around as it would create a huge drag on returns. So what happens? They buy more of the stocks in their portfolios even though the prices have changed, they get less stringent about the stocks they are willing to buy, and they add a lot of expenses in the form of incurred fees managing this new capital. The result is that these high performing funds end up underperforming with all the challenges this new capital brings. Historically there is an ebb and flow with funds where the best become the worst and the worst, the best. The worst investors are usually the ones that chase these high performing funds back and forth, underperforming the market all the way.

There are additional factors which hold back funds though. If a fund becomes too large, it might need to change its entire strategy when investments into smaller companies become impractical or will no longer work to move the needle effectively. Buffett often brags this exact point saying that he could get 50% a year if he didn’t have to manage so much money.

"it's a huge structural advantage not to have a lot of money. I think I could make you 50% a year on $1 million. No, I know I could. I guarantee that." - Warren Buffett

Other times, funds that are not performing well can be pressed by their investors to over manage investments when the best course of action would be to sit still and be patient. Or perhaps sell inexpensive losers about to break out in favor of overpriced winners on the brink of collapse (sometimes the case). The point is that these factors make it incredibly difficult for a fund to outperform the market for a long stretch of time. Closed funds and hedge funds have advantages in some of these factors over mutual funds, but the overall shortcomings should be obvious. This both points out features of modern funds that should not be replicated and demonstrates that funds are statistically not the best way to grow one’s capital over time which is Bogle’s general argument, and a pretty sound argument at that.

Bogle does concede, however, that it is not impossible to beat the market and that some have managed to do it consistently, two of the most well known being Peter Lynch and Warren Buffett. Peter Lynch took over the $18 million Fidelity Magellan fund in 1977. By the time he left it in 1990 it was worth $14 billion and had returned 29.2% per year on average. With Warren Buffett, from the time he bought Berkshire Hathaway in 1964 through to 2015, the stock price has risen by an unfathomable over 1,000,000% compared the the S&P 500 return of 2,300%.

Peter Lynch found much of his success through a buy and hold strategy composed of high quality, high growth, and cheaply valued companies relative to their growth. Much of the success of his fund was carried by the few stocks that he referred to as “multi-baggers” that increased many times over in value during his time of ownership. For Warren Buffett, widely considered the greatest investor of all time, it’s a bit more difficult to pin down his exact approach. He has changed with the times adapting his Benjamin Graham value investing strategy to more of a growth at a reasonable price approach. The Saber Capital fund manager John Huber describes Buffett's career in 3 stages.

Stage 1: Classic Graham and Dodd deep value and arbitrage (special situations)

Stage 2: Great businesses at really cheap prices (think American Express after Salad Oil Scandal, Washington Post, Disney—the first time at 10 times earnings in the 60’s)

Stage 3: Great businesses at so-so prices

He believes in buying fantastic companies that will be as successful and prevalent tomorrow as they will be in 20 years. It’s no surprise therefore that some of his largest investments have been into companies with products and services that will never (close to never) go out of style or lose demand. Some of these investments include Coca Cola, Dairy Queen, Geico Insurance, and American Express. His businesses all have large moats protecting them and loyal users with a high cost of switching. By making these types of investments he limits his downside risk enabling him to weather storms better than the market while also growing at a faster rate.

I think there are many lessons that can be learned from Bogle, Lynch, and Buffett. What is very clear is that long term investing seems to be the way to go. To put a final note on that, I will list some of its most significant advantages:

No Emotion - Emotions of fear and greed can cloud judgment and force us to make rash decisions. In the short term the market could and probably will jump all over the place but in the long term it moves in the direction of value and performance. The bumps and jumps are smoothed out. There are no decisions to be made after an investment so you can put your emotions to rest and stick to the fundamentals of the business to guide your decisions.

Time Savings - Once you make an investment, you don’t have to watch its stock price daily or monitor it very closely at all. If you are investing for the long run very little will matter day to day. After making the investment you can use your time to productively seek out new opportunities and sharpen your craft.

Statistics Are On Your Side - Mathematically, if you align your portfolio for the long term, you're more likely to make money. Although stocks do have a roughly 50-50 chance of rising or falling, they can only fall to $0, but they can rise infinitely. If you let your winners ride, there's a good chance that, over the long run you're going to see your portfolio grow in value, especially if you focus on high-quality businesses.

Commissions - The cost of trading is almost entirely removed leaving you with nothing to bring down your returns.

Taxes - When it comes time to pay taxes you will get to forgo Uncle Sam for years allowing your capital to compound freely. Then when you do collect your gains the tax rate will be much lower since investments held for more than a year are taxed at a significantly discounted rate.

Better Sleep - You will not have sleepless nights second guessing yourself and worried about the future. You can have confidence that you made the right decisions and stick by them.

These are some pretty fantastic advantages. From John Bogle we are able to see many of the shortcomings of the funds operating in the market, while Lynch and Buffett demonstrate how superior companies bought at cheap prices will win out in the long run. So there is something to be said for picking companies with sustainable competitive advantages, loyal customers, and high quality and demand products/services. It seems obvious to me that if I am to take the approach of active management, a strategy geared toward a long term buy and hold approach will ultimately yield the greatest returns.

Disclaimer: I am not a financial adviser and this is not financial advice. Above is just some observations about the strategies which have been implemented by some of the most successful investors and compared and contrasted together. I hope there was something valuable in this writing for you and thanks for reading! Feedback and contrary arguments are welcome. This is a learning process and my goal is to continue to learn and grow as an investor.

In case it wasn't clear enough, I am a fan of the value investing strategy and the strategies of Buffett, Lynch, and Bogle specifically. They are the best performers so it makes sense to me to take heed of their advice and strategies. I also think that it is important to form your own opinions though and that these types of observations could serve more as a sturdy framework than an encompassing guide.