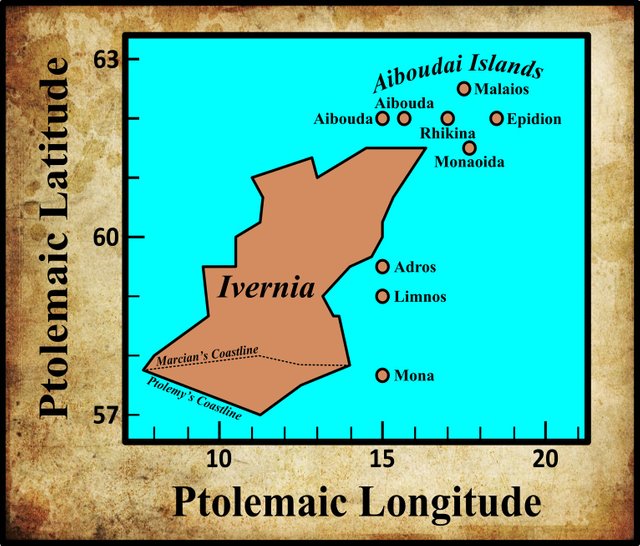

In the final section of his description of Ireland—Geography, Book 2, Chapter 2, § 10—Claudius Ptolemy records the names and coordinates of nine islands, five of which lie to the north of Ireland and four to the east. The former are known collectively as αἱ Αἰβουδαι [hai Aiboudai], or the Aiboudai (Latin: Ebudae). The two most westerly members of this archipelago share the same name, Αἰβουδα, which is simply the singular form of the feminine plural Αἰβουδαι.

I have spelt Aiboudai with the smooth breathing added to the initial diphthong (Αἰ- rather than Αι-) to clarify that the pronunciation was [aiboudai] and not [haiboudai]. The use of breathings was not fully regularized until the 9th century CE, after which all words that began with a vowel were systematically marked with the appropriate sign for “rough” (aspirated) or “smooth” (nonaspirated) breathing. (Gnanadesikan 220 ... 221). I take this to imply that Ptolemy only explicitly indicated the breathing in cases where the correct reading was not already obvious to the reader. In other words, he probably did not include the breathing in common Greek words, as its presence in such words was already well known. In the case of foreign toponyms and ethnonyms, however, he probably did include it. Hence we have Αἰβουδαι rather than Αιβουδαι.

In his 1883 edition of the Geography, Karl Müller recorded four variant readings of Αἰβουδαι, two of which differ only in their application of the Greek accents. As the use of these accents was not regularized until the Byzantine era, they are generally considered to be “without authority” (O’Rahilly 1 fn 2, Gnanadesikan 220-221). In his 1838 edition of the Geography, Friedrich Wilberg did not record any variants of this toponym, but his critical choice differs from Müller’s. In Karl Nobbe’s edition of 1845, the critical form is the same as Wilberg’s.

| Source | Greek | English |

|---|---|---|

| Müller | Αἰβουδαι | Aiboudai |

| Nobbe, Wilberg, F, L, M, N, P, R, S, Ω, Arg | Ἐβουδαι | Eboudai |

| O | Ἐβουδα | Ebouda |

| Σ, Φ, Ψ | Ἐβουδι | Eboudi |

F is Coislin 337, one of the Codices Parisini Graeci in the Bibliothèque nationale de France in Paris. It is believed to date to the 14th or 15th century.

L is a manuscript from the library at Vatopedi, the ancient monastery on Mount Athos in Greece.

M is Vindobonensis 1, a codex in the Austrian National Library in Vienna.

N and O are Oxoniensis Seldanus 2, 46 and Oxoniensis Seldanus 2, 45, two of the Selden Manuscripts in the Bodleian Library at Oxford.

P and R are Venetian manuscripts identified by Müller as Venetus 383 and Venetus 516. They are possibly kept in the Biblioteca Nazionale Marciana, though I have not been able to confirm this.

Ω, Σ, Φ and Ψ are four manuscripts from the Laurentian Library in Florence: **Florentinus Laurentianus 28, 49 : Florentinus Laurentianus 28, 9 : Florentinus Laurentianus 28, 38 : Florentinus Laurentianus 28, 42.

Arg is the Editio Argentinensis, which was based on Jacopo d’Angelo’s Latin translation of Ptolemy (1406) and the work of Pico della Mirandola. Many other hands also worked on it—Martin Waldseemüller, Matthias Ringmann, Jacob Eszler and Georg Übel—before it was finally published by Johann Schott in Straßburg in 1513. Argentinensis refers to Straßburg’s ancient Celtic name of Argentorate.

The last two variants can probably be dismissed as scribal errors for Ἐβουδαι [Eboudai]. In the first of these, the omission of the final iota has turned the toponym from the feminine plural into the feminine singular. According to Müller, this variant only occurs in a single manuscript. In the other variant, it is the alpha that has been overlooked. Significantly, this variant is only found in three closely related manuscripts from the Laurentian Library in Florence (but not in Ω, which is also from the Laurentian Library).

Other Geographers

The question, therefore, is which of the first two variants is the correct one: Αἰβουδαι [Aiboudai] or Ἐβουδαι [Eboudai]? It seems that the latter, with or without a perispomene accent (ie circumflex) on the upsilon, is the commonest form—which vindicates Nobbe and Wilberg’s choice. It is also surely significant that Ptolemy himself refers to the same islands in the Almagest 2:6 § 28 as Ἐβουδαι (deduced from the feminine genitive plural Ἐβούδων):

28 The parallel where the longest day is 19½ equinoctial hours is 62° from the equator and goes through the islands called ‘Eboudae’ [Ἐβούδων]. (Toomer 89, Heiberg 114)

62° is actually the latitude of the Faroe Islands. As we saw in one of the earliest articles in this series, Ptolemy placed Ireland and Britain several degrees northwest of their true locations.

Müller adopted the less frequent spelling Αἰβουδαι because that is the reading found in Stephanus of Byzantium, a geographer who flourished in the 6th century CE. His Ethnica, an alphabetic gazetteer of ethnographic terms, survives only in scattered fragments and an abridged epitome by an otherwise unknown scholar Hermolaus. Under the letter alpha, we find the following entry:

Aiboudai [Αἰβοῦδαι], five islands of Britain [τῆς Ρρεταννικῆς], as in the periplus of Marcian. An inhabitant is called: Aiboudaios [Αἰβουδαῖος] (Stephanus Byzantius 335)

Marcian of Heraclea was a geographer of the 4th century CE. His Periplus of the Outer Sea briefly describes Britain and Ireland, but survives only in fragments, none of which mentions the Aiboudai. Müller, whose edition of Marcian’s Periplus was published in 1882, inserts the above quotation from Stephanus to fill a lacuna in § 42 of Marcian’s text (Marcian of Heraclea 560).

Pomponius Mela was a 1st-century Roman geographer. His De Chorographia [The Chorography], a Latin description of the known world, is extant. After briefly describing Britain and Ireland, he mentions among the islands of Britain two archipelagos:

The thirty Orcades are separated by narrow spaces between them; the seven Haemodae extend opposite Germany in what we have called Codanus Bay ... (Romer 117)

The Orcades are certainly the Orkney Islands and Codanus Bay must be either the Kattegat or the Baltic Sea, as Mela places it to the east of the Elbe (Romer 109). The Haemodae are generally presumed to be the Shetland Islands, but Mela’s geography is confused and open to various interpretations. Romer glosses Haemodae as “Denmark”, which makes sense in the context of the Kattegat or Baltic Sea. Müller, however, and some other scholars have linked Mela’s Haemodae with Ptolemy’s Aiboudai. In this, Müller draws some support from Julius Honorius’s Cosmographia, which was possibly compiled in the late 4th century:

The western ocean has the following seas: The sea of the Gadean Strait; the sea which the Orcadians call the Mades Sea ... (Honorius 33)

Müller’s comment on this:

The name Hæmodæ, which is used by Mela, seems to have been known even by Julius Honorius in his Cosmographia ... where we have this: The sea which the Orcadians call the Mades Sea (ie the Emades Sea or the Emodes Sea. Cf. Lochmaddy on the island of North Uist [in the Outer Hebrides]). (Müller 81)

Pliny the Elder, who compiled his encyclopedic Natural History in the second half of the 1st century CE, is clearly drawing upon Mela as one of his sources when he enumerates the islands of Britain in Book 4, Chapter 30, but he distinguishes the Acmodæ (as he called them) from the Hæbudes, which are not mentioned by Mela:

Of the remaining islands none is said to have a greater circumference than 125 miles. Among these there are the Orcades, forty in number, and situate within a short distance of each other, the seven islands called Acmodæ, the Hæbudes, thirty in number ... (Pliny et al 351)

Pliny’s translators John Bostock and Henry Thomas Riley add the following gloss to Pliny’s Acmodæ:

Also called Æmodæ or Hæmodæ, most probably the islands now known as the Shetlands. Camden however and the older antiquarians refer the Hæmodæ to the Baltic sea, considering them different from the Acmodæ here mentioned, while Salmasius on the other hand considers the Acmodæ or Hæmodæ and the Hebrides as identical. Parisot remarks that off the West Cape of the Isle of Skye and the Isle of North Uist, the nearest of the Hebrides to the Shetland islands, there is a vast gulf filled with islands, which still bears the name of Mamaddy or Maddy, from which the Greeks may have easily derived the words Αἱ Μαδδαὶ [Hai Maddai], whence the Latin Hæmodæ. (Pliny et al 351)

Today, this stretch of water is called The Little Minch. North Uist is not the nearest of the Hebrides to the Shetland Islands. That distinction belongs to Lewis and Harris.

Hebrides or Hebudes

Whatever might be the relationship between Ptolemy’s Aiboudai, Mela’s Hæmodæ, and Pliny’s Acmodæ and Hæbudes, it is generally accepted today that the Aiboudai refer to the Hebrides, a large group of islands off the west coast of Scotland, which are also known as the Western Isles.

Although T F O’Rahilly did not include the islands in his analysis of Ptolemy’s description of Ireland, he did later add a lengthy additional note on the subject to his Early Irish History and Mythology:

Ptolemy in his account of Ireland speaks of five islands called Ebudae (Ἔβουδαι) lying to the north of Ireland, and he gives their names as Ebuda (two islands so called), Rikina, Malaios and Epidion. [Footnote 5: Pliny, writing somewhat earlier, refers to xxx Hebudes, but gives no further information about them. From a misreading of Pliny’s text the modern ‘Hebrides’ has been borrowed.] Similarly Solinus speaks of Ebudes insulae quinque numero. If one may rely on Ptolemy, it would appear that the name Ebudae was applicable, not to all the Hebrides, but only to the most southerly of the Scottish islands, those nearest to Ireland.

The corresponding Irish name is applied, not to the islands, but to their inhabitants, viz. *Ibuid (< *Ebudī), gen. *Ibod. It has been preserved in the phrases Tuath Iboth and Fir Iboth, in which the final -th is perhaps to be explained as due to the influence of the O. Ir. gen. pl. Uloth, ‘of the Ulaid’. A later form of the name was Ibdaig, which stands to *Ibuid as Bretnaig stands to Bretain or Cruithnig to Cruthin. Oenges, brother of Muiredach Muinderg, (king of Ulaid, ca. A.D. 490), acquired the cognomen Ibdach (or Ibthach) because his mother was a woman of the Ibdaig.

From Iboth, eponymous ancestor of the Tuath Iboth or Ibdaig, descend also, according to one account, the Uaithni, whom Ptolemy calls Auteini, and whom he locates approximately in the present Co. Galway ... this may have some connexion with the fact that some of the Fir Bolg of Connacht, among whom we may reckon the Auteini, are traditionally said to have taken refuge in certain of the Scottish islands [when Connacht was invaded and conquered by the Lagin]. (O’Rahilly 537-538)

O’Rahilly cites no source for his claim in the footnote that a misreading of Pliny’s Hebudes as Hebrides is the origin of the modern name (but see Chisholm 192, Watson 37). This error, it seems, arose in the early 16th century but it was not until almost two hundred years that the Scottish antiquarian John Pinkerton tracked it to its source. The relevant passage, I believe, deserves to be quoted at length:

Our writers are so ignorant concerning them, that they have even, for more than two centuries, perverted the very name in an odd manner. For since the publication of the notorious History of Hector Boethius at Paris, 1526, folio, our writers have called these iles Hebrides. I have taken some pains to detect the origin of this blunder. The edition of Pliny 1469, folio, Venetiis, bears ebudes. That of Solinus, 1473, folio, ib. also bears Ebudes. The Solinus of Aldus, 1518, 8vo. has Hæbudes; as have all the editions of Pliny and Solinus since ... But Pliny and Solinus were the writers whom Boethius followed ; and I was beginning to impute his Hebrides to an error of himself, an amanuensis, or the printer Badius Ascensius. However I chanced upon an edition of Solinus, in which the very source of this error appeared. Its title is, Solinus de Memorabilibus Mundi, diligenter annotatus et indicio alphabetico prenotatus. In a wooden print is the name of the bookseller Denis Roce, Parisiis: and on the back of the title is a dedication by Badius Ascensius the printer to John De Falce, dated ad idus Julias, M. D. III. The book was printed that year, 1503, as appears from this date and from its whole form, agreeing with the rude Paris press of the end of the fifteenth century, and beginning of the sixteenth century, before the Stephani arose. This edition is so full of typographic errors, that it is a disgrace to printing ... in folio xxii, excipiunt EBRIDES insulæ, quinque numero, appears in the text ; and on the margin Ebrides; as also in the index prefixt, Ebrides ... As Boethius studied at Paris, whence he was called to a professor’s chair at Aberdeen, it seems evident that he had picked up this edition of Solinus; and having no other to consult in Scotland, took his Hebrides from this clear fountain. Such being the case, and the name Hebrides [Footnote: Late Irish writers say that the Hebrides are so called from king Hiber.] a mere blunder, the condition of learning, and of antiquarian studies in particular, among us of Scotland, may be more easily guessed at from this simple circumstance, than from any argument. With us a mere typographic error remained, and passed among all our writers, save Buchanan, for more than two centuries and a half. In any other country such a matter would have been detected at once. And I should not wonder to see our writers persist in Hebrides, from mere shame; as the old priest retained his Mumpsimus for Sumpsimus. But our error is confined to ourselves, for all foreign writers ever put Hebudes.

(Pinkerton 300-302)

Pinkerton’s footnote that late Irish writers derived Hebrides from a King Hiber is based on a passage in Hector Boece’s Scotorum Historia [History of the Scots], the very work that introduced this alleged error to Scotland. Clearly, Boece is referring to the legendary Milesian king Éber:

4 Our national writers refer the Scottish name to Egypt and the time of Moses. For they that say that a Greek named Gathelus, a man born of royal blood, took to wife the daughter of Pharaoh, king of the Egyptians, and that her name was Scota. But he soon came to think that ruin was impending for Egypt, since he saw it suffering the plagues of which Holy Scripture tells us, and, gathering companions, who were partly Greek and partly Egyptian, and taking his wife, he sailed out into our sea in order to remove himself as far as possible from the danger, and settled the northernmost extremity of Spain, calling his people Scottish after the name of his wife, so as to make them more loyal to himself after they had lost their homeland. After a number of years had passed, he led to Ireland a colony recruited from these Scots, and, thanks to their excellent virtue of mind and body, they soon gained rule over the entire Ireland, as well as great glory. And not long thereafter, they say, Rothesaus, the son of a certain Irish king, took a choice band of young men and crossed over to the Hebrides, so-called because they were named after Hiberus, the son of King Gathelus, or because these people came from Hibernia or Ireland, although some people called these islands the Eboniae. From there they had a direct passage to Albion, I mean the part facing the Hebrides, which was deserted at the time, since the rule of the British did not yet stretch that far, they being so few in number. They say that the year in which the Scots entered Albion was more than 4617 after the world’s beginning. (Boece, Boethius folio 4)

Against this one should note the disclaimer with which Dana F Sutton introduces his translation of Boece’s History:

At the very outset, it is necessary to explain the need for a modern edition and translation of a work with so evil a reputation as the Scotorum Historia by Hector Boece [1465 - 1536], first printed at Paris in 1527 and republished at Paris in 1575 as supplemented by the Italian Humanist Giovanni Ferrerio. The chief problem is that for the earlier part of his history down to the reign of Malcolm Canmore, as he never tires of reminding us, Boece relied on an early source called “Veremund,” and since no historian of that name was known, ever since a seminal 1729 essay by Thomas Innes Boece has lain under deep suspicion of having been deceived by a forgery or, even worse, of having manufactured all that he wrote about the first forty kings of Scotland out of whole cloth. He has, therefore, often been written off, and sometimes derided, as a romancing liar, more or less the Scottish equivalent of Geoffrey of Monmouth, not to be taken seriously. (Sutton 1)

Let us not pursue this subject any further, but merely note that while Hebrides probably owes its origin to a simple typographical error, there nevertheless remains a slender possibility that this is not the case.

Identification

Of more interest to our present research is O’Rahilly’s suggestion that the name Aiboudai or Ebudae was originally restricted to the southernmost of the Scottish isles, such as Islay and Jura, both of which can be seen from the northeastern corner of Ireland. Is it possible that these are the two islands to which Ptolemy gave the name Aibouda? I am not the first to light upon this idea. In his paper of 1894, Goddard Orpen wrote:

As to the islands, the two Αἰβοῦδαι (al. Ἐβοῦδαι) are probably Islay and Jura ... (Orpen 127)

Alternatively, the fact that Ptolemy enumerates among the Aiboudai two islands with the name Aibouda could simply be a reflection of the fact that the Hebrides comprise two disparate archipelagos: the Outer Hebrides and the Inner Hebrides. Did Ptolemy or his source garble an account that told of two groups of Aiboudai—the Outer Aiboudai and the Inner Aiboudai? This is more or less what Louis Francis has suggested, though I find most of his identifications impossible to accept:

§11 is concerned with a group of five [islands] under the general heading of ‘Ebuda’ which would appear to be the Outer Hebrides, while further to the east another group, among which another island also called ‘Ebuda’, would appear to be the Inner Hebrides and finally ‘Epidium’, taken to be the Kintyre peninsula. (Francis)

Müller suggested that the two Aiboudas referred to North Uist and South Uist, two of the larger islands in the Outer Hebrides, simply because they share the same name even today (Müller 81). The Scottish photographer and historian Captain Thomas also identified them with North and South Uist (Watson 37).

The toponymist William John Watson anticipated O’Rahilly in suggesting that Aiboudai might have been formerly restricted to a much smaller subset of the Western Isles:

It may be worth mentioning that we have in Gaelic the combination Bód is Ìle is Arainn, Bute and Islay and Arran—I have heard it in the west—and Irish tradition joins Ara ⁊ Íla ⁊ Rechra, Arran and Islay and Rathlin; Íle is Ara are coupled too in St. Berchan’s ‘Prophecy.’ It may be that here we have an indication of an old group corresponding to the Eboudai. (Watson 37-38)

Arran and Bute are islands in the Firth of Clyde, to the east of Kintyre. Islay and Jura lie to the west of Kintyre. Watson also believed that there was no etymological connection between the toponyms Bute and Ebudae:

Bute is in Gaelic Bód, gen. Bóid ... The suggestion has been made that Bód is connected with Ebudae, the Hebrides, but this is quite impossible. A possible explanation is O. Ir. bót, fire, if we suppose, as is likely, that the original name was Inis Bóit, ‘isle of fire,’ with reference to signal fires or bale fires. (Watson 95 ... 96).

Etymology

One of the principal reasons I undertook this investigation of Ptolemy’s description of Ireland was to see whether the toponyms and ethnonyms recorded by Ptolemy lend any support to the claims of mainstream academia that these islands were inhabited by pre-Celtic and pre-Indo-European peoples for thousands of years before the Celtic languages came to be spoken here. If this were true, we would expect to find a plethora of pre-Indo-European names among those recorded by Ptolemy. If, on the other hand, the Short Chronology is correct, which asserts that the earliest post-glacial settlers of these islands were the Celtic Priteni of about 750 BCE, then we would not expect to come across any pre-Celtic place names in Ptolemy’s text.

So what is the etymology of Ptolemy’s Aiboudai or Pliny’s Hebudae? At least one scholar, William John Watson, has suggested that the name may be pre-Celtic. His classic text The History of the Celtic Place-Names of Scotland is an expanded version of a series of lectures—the 41st Rhind Lectures—which he delivered to the Society of Antiquaries of Scotland in Edinburgh in 1916:

The meaning of Eboudae is unknown, and the word is probably pre-Celtic. (Watson 38)

In the early 18th century, William Baxter was also somewhat perplexed:

EBUDÆ or Ebudes, usually given corruptly as Hebrides ... are islands of unknown number situated in the Deucaledonian Sea ... Neither Evaüd nor Evon (for the Ebudæ are called by some Eboniæ and Evones) signifies anything other than island. For amongst the ancients Aü or Eü meant sea as well as island ... Moreover, the most diligent describer of these islands Martin shows that among the modern inhabitants of the Hebrides Au stands for ocean. (Baxter 119)

Contrast this with William Mackenzie’s account from 1903, which is replete with conjectural Celtic etymologies:

It is unnecessary to enter into a detailed discussion of place-names in the Outer Hebrides, other than those of the islands which compose the group. The word “Hebrides” itself is puzzling, etymologists not being in agreement [Footnote: Boece derives the name from Hibernia, or from King Hiber; Camden, from Ebeid, signifying without corn; Dr. Macpherson, from Ey-budh, the islands of corn, or from Saint Bridget; Pinkerton and Laing from Ey-Bud or Ey-Buth, island-habitation.] In the best editions of Pliny and the manuscripts of highest authority, the name appears as “Haebudes” or “Hebudes,” the modern form having, however, been also used both by Pliny, and in an edition of Solinus. From “Hebudes” was evolved the form “Ebudae,” used by the writers of the first and second centuries. If one more guess may be added to the list of origins, it is that the word “Hebrides” may mean the Islands of Brude, Bruidi, Bridei, or Buidhe. There are no fewer than thirty Brudes in the first series of Pictish kings, and six Bruidis or Brideis in the second. The islands have also been called Beteoricae, Inchades, Ebonides, and Leucades. They were known, too, as Iniscead, and Innis Cat, i.e. the Hundred Isles, and the Islands of the Catani. (Mackenzie xxxvi)

Going back to the late 19th century, we have James Brown Johnston, who suggests an Old Gaelic (ie Old Irish) etymology:

HEBRIDES. c. 120, Ptolemy, Ebudae (prob., too, the same word as the Epidii, who, according to him, inhabited most of modern Argyle); Solinus, Polyhistor., 3rd century, Hebudes (Ulst. Ann., ann. 853, Innsegall, ‘isles of strangers,’ i.e., Norsemen; and always called by the Norsemen ‘Sudreys’ or Southern isles to distinguish them from the Northern Orkneys, &c., the ‘Nordreys’). Origin unknown; possibly Old G. c(h)abad, a head, or c(h)àbadh, a notching, indenting. The u is supposed to have become ri through some early printer’s error. (Johnston 131)

The etymologists at Roman Era Names have also suggested an Indo-European origin for this toponym, though not necessarily a Celtic one:

The natural meaning of *ebuda is something like ‘off out’, based on PIE *apo- ‘off’ plus *ūt- ‘out’, but it is hard to point to a specific language family in which the name was built. B shows up well in Germanic, for example in English ebb or Dutch buiten ‘outside’, or in Latin in the prefix ab-, while D shows up in Danish and Sanskrit, plus possibly Greek ουδος ‘threshold’. R&S [A L F Rivet, C Smith, The Place-Names of Roman Britain, Batsford, London (1979] could find no etymology within Celtic. (Roman Era Names)

In Conclusion

In my opinion, Ptolemy’s Aiboudai and the two islands he calls Aibouda raise problems that have not yet been resolved. The etymology of these names and the identities of the two islands are still uncertain—though there can be little doubt that Aiboudai refers to some if not all of the Hebrides.

Once it is conceded that the Aiboudai are the Hebrides, it becomes almost a matter of choice which of the Western Isles are to be identified with the two Aiboudas. As we have seen, Orpen opted for Islay and Jura, two of the closest to Ireland. Müller and Captain Thomas chose the two Uists, while Louis Francis identified them with the Outer and Inner Hebrides. In 1814, the Irish antiquary Fr Charles O’Conor confidently identified the two Ebudas with Uist and Lewis (O’Conor liii).

The French scholar André Berthelot, on the other hand, excluded these islands from his analysis, believing that the problems they raised had more to do with the history of navigation than the geography of Ireland (Berthelot 247). This is probably the wisest course to steer, but if I were pressed, I would probably side with Goddard Orpen and identify the two Aiboudas with Islay and Jura, two large Hebridean isles visible from Ireland.

References

- William Baxter, Glossarium Antiquitatum Britannicarum, sive Syllabus Etymologicus Antiquitatum Veteris Britanniae atque Iberniae temporibus Romanorum, Second Edition, London (1733)

- André Berthelot, L’Irlande de Ptolémée, in Revue Celtique, Volume 50, pp 238-247, Librairie Ancienne Honoré Champion, Paris (1933)

- Hector Boethius, Scotorum Historiae a Prima Gentis Origine, Jodocus Badius Ascensius, Paris (1526)

- Hector Boece, Scotorum Historia (1575 Edition), Dana F Sutton, The Philological Museum, The Shakespeare Institute of the University of Birmingham (2010)

- William Camden, Britannia: Or A Chorographical Description of Great Britain and Ireland, Together with the Adjacent Islands, Second Edition, Volume 2, Edmund Gibson, London (1722)

- Hugh Chisholm (editor), The Encyclopaedia Britannica, Eleventh Edition, Volume 13, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge (1911)

- Patrick S Dinneen, Foclóir Gaedhilge agus Béarla: An Irish-English Dictionary, New and Revised Edition, Irish Texts Society, M H Gill & Son, Ltd, Dublin (1927)

- Louis Francis (editor, translator), Ptolemy’s Geographia: Selections, English, University of Oxford Text Archive (1995)

- Amalia E Gnanadesikan, The Writing Revolution: Cuneiform to the Internet, Blackwell Publishing, John Wiley & Sons, Ltd, Chichester (2009)

- Johan Ludvig Heiberg, Syntaxis Mathematica, Volume 1, B G Teubner, Leipzig (1898)

- Julius Honorius, Cosmographia, in Alexander Riese, Geographi Latini Minores, pp 21-55, Henninger Brothers, Heilbronn (1878)

- William Cook Mackenzie, History of the Outer Hebrides (Lewis, Harris, North and South Uist, Benbecula, and Barra), Alexander Gardner, Paisley (1903)

- Marcian of Heraclea, Periplus of the Outer Sea, in Karl Müller, Geographi Græci Minores, Volume 1, pp 515-562, Firmin-Didot, Paris (1882)

- Martin Martin, A Description of the Western Islands of Scotland, Second Edition, Andrew Bell, London (1716)

- Emmanuel Miller, _Périple de Marcien d’Héraclée, Epitome d’Artémidore, Isidore de Charax, etc., ou, Supplément aux Dernières Éditions des Petits Géographes : D’après un Manuscrit Grec de la Bibliothèque Royale _, L’Imprimerie Royale, Paris (1839)

- Karl Wilhelm Ludwig Müller (editor & translator), Klaudiou Ptolemaiou Geographike Hyphegesis (Claudii Ptolemæi Geographia), Volume 1, Alfredo Firmin Didot, Paris (1883)

- Karl Friedrich August Nobbe, Claudii Ptolemaei Geographia, Volume 1, Karl Tauchnitz, Leipzig (1845)

- Karl Friedrich August Nobbe, Claudii Ptolemaei Geographia, Volume 2, Karl Tauchnitz, Leipzig (1845)

- Charles O’Conor, Rerum Hibernicarum Scriptores Veteres, Volume 1, Prolegomena, Pars I, John Seeley, Buckingham (1814)

- Thomas F O’Rahilly, Early Irish History and Mythology, Dublin Institute for Advanced Studies, Dublin (1946, 1984)

- Goddard H Orpen, Ptolemy’s Map of Ireland, The Journal of the Royal Society of Antiquaries of Ireland, Volume 4 (Fifth Series), Volume 24 (Consecutive Series), pp 115-128, Dublin (1894)

- John Pinkerton, An Inquiry into the History of Scotland Preceding the Reign of Malcolm III, Volume 2, John Nichols, London (1794)

- Pliny the Elder, John Bostock, Henry Thomas Riley, The Natural History of Pliny, Volume 1, Henry G Bohn, London (1855)

- Pliny the Elder, Naturalis Historia, Giovanni and Vindelino da Spira, Venice (1469)

- Claudius Ptolemaeus, Geography, Biblioteca Apostolica Vaticana, Vat Gr 191, fol 127-172 (Ireland: 138v–139r)

- F E Romer, Pomponius Mela’s Description of the World, The University of Michigan Press, Ann Arbor MI (1998)

- Gaius Julius Solinus, De Memorabilibus Mundi Diligenter Annotatus et Indicio Alphabetico Prenotatus, Jodocus Badius Ascensius, Paris (1503)

- Stephanus Byzantius, August Meineke (editor), Ethnica, Georg Reimer, Berlin (1849)

- Rudolf Thurneysen, Osborn Bergin (translator), D A Binchy (translator), A Grammar of Old Irish, Translated from Handbuch des Altirischen (1909), Dublin Institute for Advanced Studies, Dublin (1946, 1998)

- G J Toomer (translator & annotator), Ptolemy’s Almagest, Gerald Duckworth & Co Ltd, London (1984)

- William John Watson, The History of the Celtic Place-Names of Scotland, Edinburgh (1926)

- Friedrich Wilhelm Wilberg, Claudii Ptolemaei Geographiae, Libri Octo: Graece et Latine ad Codicum Manu Scriptorum Fidem Edidit Frid. Guil. Wilberg, Essendiae Sumptibus et Typis G.D. Baedeker, Essen (1838)

Image Credits

- Ptolemy’s Map of Ireland: Wikimedia Commons, Nicholaus Germanus (cartographer), Public Domain

- Greek Letters: Wikimedia Commons, Future Perfect at Sunrise (artist), Public Domain

- South Uist in the Outer Hebrides: © West Highland Free Press 2018, Fair Use

- The Little Minch: © Oliver Dixon, Creative Commons License

- T F O’Rahilly: Copyright Unknown, Fair Use

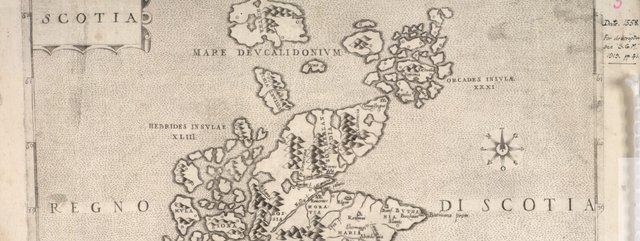

- Scotia: Regno di Scotia (Anonymous, ca 1558-1566: National Library of Scotland, Creative Commons License

- Jura: Small Isles Bay and the Paps of Jura: © Andrew Curtis, Creative Commons License

- The Oa, Islay: © Whaleman30, Creative Commons License

- Lewis and Harris (Outer Hebrides): © 2019 Lucy Dodsworth/On the Luce, Fair Use

- Carrick-a-Rede Ropebridge: © niviews, Fair Use

This post was shared in the Curation Collective Discord community for curators, and upvoted and resteemed by the @c-squared community account after manual review.

@c-squared runs a community witness. Please consider using one of your witness votes on us here

Downvoting a post can decrease pending rewards and make it less visible. Common reasons:

Submit

wow what interesting History/geography

Downvoting a post can decrease pending rewards and make it less visible. Common reasons:

Submit