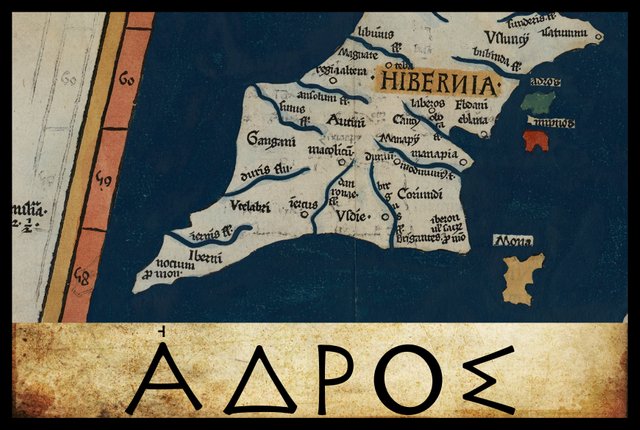

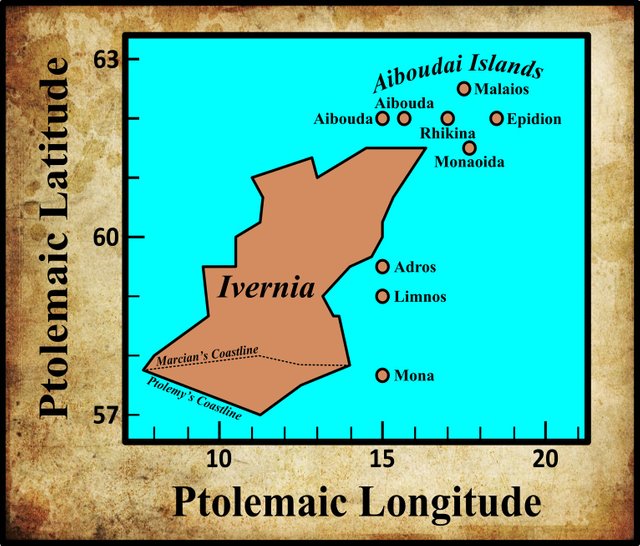

In the final section of his description of Ireland—Geography, Book 2, Chapter 2, § 10—Claudius Ptolemy records the names and coordinates of nine islands, five of which he places to the north of Ireland and four to the east. The third of the four eastern islands is called Ἀδρου ἐρημος [The Desert Island of Adros].

In his 1883 edition of the Geography, Karl Müller records two variant readings of Ἀδρου, and one minor variant in the latitude: 59° 20' in place of the usual 59° 30'. In his 1838 edition of the Geography, Friedrich Wilberg records the same three readings as Müller but chooses one of Müller’s variants as the critical reading. He does not record any variant coordinates. In Karl Nobbe’s edition of 1845, the critical reading agrees with Wilberg’s:

| Source | Greek | English |

|---|---|---|

| Müller, X, Σ, Φ, Ψ, Arg | Ἄδρου | Adrou |

| Wilberg, Nobbe, Most MSS | Ἔδρου | Edrou |

| B, E, L2, Z | Ὄδρου | Odrou |

| Source | Latin | English |

|---|---|---|

| 4803 | Adros que deserta ē | Adros, which is deserted |

X is Vaticanus Graecus 191, which dates from about 1296. It is thought that this manuscript preserves a very ancient tradition. Ptolemy’s description of Ireland is on folia 138v and 139r.

Σ, Φ and Ψ are three manuscripts from the Laurentian Library in Florence: Florentinus Laurentianus 28, 9 : Florentinus Laurentianus 28, 38 : Florentinus Laurentianus 28, 42.

Arg is the Editio Argentinensis, which was based on Jacopo d’Angelo’s Latin translation of Ptolemy (1406) and the work of Pico della Mirandola. Many other hands also worked on it—Martin Waldseemüller, Matthias Ringmann, Jacob Eszler and Georg Übel—before it was finally published by Johann Schott in Straßburg in 1513. Argentinensis refers to Straßburg’s ancient Celtic name of Argentorate.

B and E are two of the Codices Parisini Graeci in the Bibliothèque nationale de France in Paris: Grec 1404 and Grec 1403 respectively.

L is a manuscript from the library at Vatopedi, the ancient monastery on Mount Athos in Greece. Müller makes a distinction between L and L2, but he never clarifies what this distinction entails.

4803 is one of the Codices Parisini Latini in the Bibliothèque nationale de France in Paris. It is a Latin translation of Ptolemy’s Geography by Jacopo d’Angelo: Latin 4803. This manuscript gives the latitude as 59 1/3, while all other manuscripts have 59 1/2. It is safe to dismiss this as an error, though Ptolemy’s 59 1/2 is probably an arbitrary value that Ptolemy himself invented.

As usual, I choose to spell this toponym with the smooth breathing (Ἀ rather than Α) to clarify that the pronunciation was [adrou] and not [hadrou]. The use of breathings was not fully regularized until the 9th century CE, after which all words that began with a vowel were systematically marked with the appropriate sign for “rough” (aspirated) or “smooth” (nonaspirated) breathing. (Gnanadesikan 220 ... 221). I take this to imply that Ptolemy only explicitly indicated the breathing in cases where the correct reading was not already obvious to the reader. In other words, he probably did not include the breathing in common Greek words, as its presence in such words was already well known. In the case of foreign toponyms and ethnonyms, however, he probably did include it. Hence we have Ἀδρου rather than Αδρου.

There are two things in particular to note concerning the names of this island and the following one. Firstly, they are qualified with the adjective ἐρημος:

ἐρημος Desolate, lonely, lonesome, solitary ... (Liddell & Scott 577)

Presumably, this means that these islands were uninhabited. ἐρημος, I take it, stands for νησος ἐρημος, desert island. Note that while νησος [nēsos], island, is a feminine noun, it was common practice to qualify it with the masculine form of the adjective (Smyth 74).

The second thing to note about the last two names in Ptolemy list of “Irish” islands is the grammatical case. In my opinion, Ἀδρου [Adrou] is the genitive case of Ἀδρος [Adros]. Ἀδρου ἐρημος means, I believe: Desert [Island] of Adros. Müller too suspected that this was the case:

It may be asked whether this line and the following correctly have ου [ou] or whether this ending was derived from ος [os]. (Müller 81)

Not everyone agrees with this analysis, however. In 1922, James Fraser rebutted it in a short article that appeared in the Revue Celtique:

Ptolemy in his description of Britain [sic] mentions among the islands off the coast one which he calls Αδρου ἔρημος i. e. A. a desert island. The mistaken idea that ἔρημος was a substantive evidently led Holder, Altcelt, Sprachschatz s. v., as it may have led Pliny, into giving the name of the island as Adros (Pliny has Andros); but there can be no doubt whatever that the name is Adrū. So Macbain, Ptolemy’s Geography of Scotland, 1911 [MacBain 31]. From the so-called map of Ptolemy it will appear that this island is approximately in the latitude of the Cheshire Dee; hence the inevitable identification with Benn Edair, Howth Head. But Adrū is also in the latitude of the Selgovae, who were probably settled to the North of the Solway Firth, and of the Firth of Clyde. The composite character of Ptolemy’s map is well known and accounts for the distortion which puts the Solway Firth and the Firth of Clyde on the same latitude instead of, roughly, on the same longitude. Ptolemy’s sources did, however I believe, give the same longitude for Adrū and the Firth of Clyde; and the island ought to be identified with Arran, Gael. Árainn d. sg. of Áru, Ára.

This involves some conclusions of linguistic interest. In the first place, the island name was, at latest in the second century A. D, of the form of the n. sg. of a -jen- stem. Ptolemy’s Ἀλουίων, as the retention of the final -n shows, cf. Gaulish Sebođđu, dates from an earlier period. It is, therefore, possible that j had already disappeared after the group dr; its absence may, however, be due to Ptolemy’s authorities. In the second place, it must be assumed that the treatment of the group dr in intervocalic position was in the Goidelic, as in the British, dialects, parallel to that of gr. The view that dr became in Irish tr (Pedersen, o. c. I, 112) rests on a weak foundation. (Fraser 353-354)

I find this unconvincing. The fact that Pliny has Andros and not Adros is simply waved away. Fraser then draws linguistic conclusions from his unproven hypothesis, when he ought to be building his hypothesis upon well-established linguistic principles. Nevertheless, the possibility should be borne in mind that Adrou is the correct name of the island.

Patrick Weston Joyce drew the opposite conclusion to Fraser:

There is one very interesting example of the complete preservation of a name unchanged, from the time of the Phoenician navigators to the present day. Just outside Eblana there appears a small island, which is called Edri Deserta on the map, and Edrou Heremos in the Greek text, i. e. the desert of Edros; which last name, after removing the Greek inflexion, and making allowance for the usual contraction, regains the original form Edar. This is exactly the Irish name of Howth, used in all our ancient authorities, either as it stands, or with the addition of Ben (Ben-Edair, the peak of Edar); still well known throughout the whole country by speakers of Irish; and perpetuated to future time in the names of several villa residences built within the last few years on the hill. (Joyce 80)

This leaves only one matter to resolve: which one of the three variant readings is correct?

- Ἀδρος [Adros], Ἐδρος [Edros], Ὀδρος [Odros]

Wilberg and Nobbe chose Edros as the critical form because it was supported by the majority of extant manuscripts. The other two variants are found in only four manuscripts each. Müller, however, opted for Adros because it was supported by Pliny the Elder. In his Natural History, Pliny gives a list of islands off the shores of Britain and Ireland:

This last island [Hibernia] is situate beyond Britannia ... Of the remaining islands none is said to have a greater circumference than 125 miles [200 km]. Among these there are the Orcades, forty in number, and situate within a short distance of each other, the seven islands called Acmodæ, the Hæbudes, thirty in number, and, between Hibernia and Britannia, the islands of Mona, Monapia, Ricina, Vectis, Limnus, and Andros. (Pliny 351)

Müller was surely right to identify Pliny’s Andros with Ptolemy’s Adros. In the evolution of Indo-European and Proto-Celtic into Old Irish, nasal sounds were lost before certain plosive sounds, as Rudolf Thurneysen noted in A Grammar of Old Irish. He even cited this particular toponym as an example of this phenomenon:

208 Nasals are lost before t- and k- sounds, which become the unlenited (geminated) mediae d and g ... A preceding ... ăn become[s] é in stressed syllables ...

If Andros (Pliny) and Ἄδρου ἔρημος (Ptolemy) correspond to later Benn Étair ‘Hill of Howth’ (Pokorny, ZCP. xv. 195), they may be regarded as representing the pronunciation ądr- (< antr-). (Thurneysen 126-127)

T F O’Rahilly agreed that Ptolemy’s Adros referred to the peninsula of Howth, which forms the northern boundary of Dublin Bay and is only connected to the mainland by a narrow tombolo (the Isthmus of Sutton). But O’Rahilly also believed that Ptolemy’s Adros was corrupt:

In Adros (Ἄδρου ἔρημος), which appears in Pliny as the island of Andros, we may have a corruption of *Antro-, Ir. Étar, the Hill of Howth, assuming the latter was mistaken for an island. Compare Antros, the name of an island in the Garonne (Holder, s.v.). (O’Rahilly 14)

Why did O’Rahilly regard this as corrupt? As we have already seen, O’Rahilly proved that Ptolemy’s description of Ireland was not based on contemporary data, but on information gathered in Ireland about 450 years before Ptolemy’s time. O’Rahilly believed that Pytheas of Massalia, who visited these islands around 325 BCE, was Ptolemy’s principal source for the geography of Ireland. O’Rahilly, it seems, extended this hypothesis to the nine “Irish” islands as well. Therefore, he must have argued, Ptolemy would have recorded an older form of the name of this island than Pliny. But the loss of the -n- in Andros clearly occurred after Pliny’s time. Therefore, Ptolemy’s Adros must be corrupt.

But as I have suggested, O’Rahilly’s Pythean hypothesis only applies to the mainland features of Ireland. The nine islands are simply all the small islands to the west of Britain of which Ptolemy knew, and which he arbitrarily ascribed to Ireland. They are not really “Irish” and do not properly belong to the description of Ireland. Ptolemy’s source for these islands was patently a contemporary British source. Therefore, it is not at all surprising to find Ptolemy recording the name of Pliny’s Andros as Adros. Ptolemy compiled his Geography about seventy years after Pliny compiled his Natural History. It must have been during this period that the -n- in Andros was lost.

Before proceeding, let’s take a look at those sources cited by Thurneysen and O’Rahilly: Pokorny and Holder.

At the turn of the 19th century, the Austrian linguist Alfred Holder compiled a three-volume lexicon of early Celtic terms. The entry for Antros is a quotation from Pomponius Mela’s Description of the World:

The Garunna [Garonne], which descends from the Pyrenees, flows shallow for a long time and is barely navigable except when swollen by winter rain or melted snow. But when it has been increased by the intrusions of the seething Ocean, and while those same waters are receding, the Garunna drives on its own waters and those of Ocean. The river, being considerably fuller, becomes wider the farther it advances, and at the end it is like a strait. It not only carries bigger ships but rises like the raging sea and violently buffets those who sail it, at least if the wind pushes one way and the current another. 22. In the river is the island named Antros, which the locals think floats on the surface and is raised up by the rising waves. (Romer 107-108, Holder 162)

The Bohemian linguist Julius Pokorny also identified Pliny’s Andros and Ptolemy’s Adros with the peninsula of Howth. In the paper cited by Thurneysen he was responding to the article by J Fraser to which reference has already been made. After a long and convoluted argument, he concludes:

This spelling, Ἀνδρος rather than the expected Ἀντρος, can be very easily explained, as, due to a well-known phonetic shift in late Greek, medieval manuscripts often replace ντ with νδ. The form with νδ must have already existed in Pliny’s day. (Pokorny 1925:196)

It is curious that Pokorny explains the transition from -t- to -d- as a phonetic shift that occurred in late Greek, while Thurneysen sees it as part of the natural evolution of the Celtic languages.

Identity

As we have seen, recent scholarship has generally identified Ptolemy’s Adros and Pliny’s Andros with the peninsula of Howth. The earliest native name for this feature is Étar or Benn Étair. Patrick Weston Joyce offers the following traditional origin for the native name:

According to some Irish authorities, the place received the name of Ben-Edair from a Tuatha De Danann chieftain, Edar, the son of Edgaeth, who was buried there; while others say that it was from Edar the wife of Gann, one of the five Firbolg brothers who divided Ireland between them. The name Howth is Danish. It is written in ancient letters Hofda, Houete, and Howeth, all different forms of the northern word hoved, a head (Worsae [324]). (Joyce 81)

It was common for ancient toponyms to be explained by linking them to a mythical or historical character. This practice led to the compilation of a large corpus of stories in both verse and prose recounting how various features of the Irish landscape acquired their present names—the so-called Dindsenchas.

It is therefore unlikely that Benn Étair was named for an individual called Étar. If the name goes back to Proto-Celtic *Antros, then perhaps this is its etymology:

antro-m, cave, air hole (Pokorny 1959:50)

Earlier Scholarship

It was only quite recently that Ptolemy’s Adros came to be identified with the peninsula of Howth (Modern Irish: Édar). The Irish antiquarian Fr Charles O’Conor, writing in 1814, was one of the first to do so (O’Conor liii). Earlier scholars suggested several other candidates.

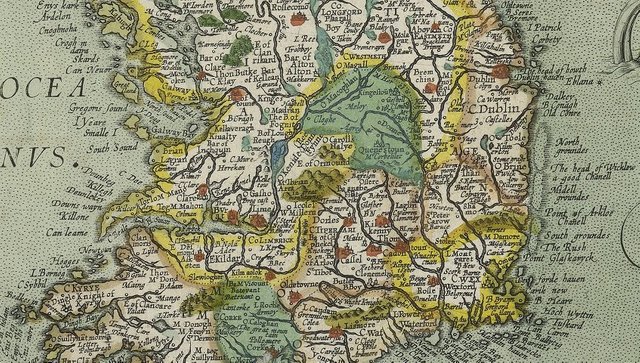

William Camden identified it with Bardsey Island, which lies about 50 km to the south of Anglesey Island, off the Llŷn Peninsula in Wales:

the Island ... call’d at present by the Welsh Enbly, and by the English Berdsey, that is, an Island of Birds. One may safely infer from the signification of the word, that this is it, which Ptolemy calls Edri, and Pliny Andros, or Adros, as some Copies have it. For Ader among the Britains signifies a bird; and so the English in the same sense call’d it afterwards Berdsey. The name Enbly is modern, and deriv’d from a certain Religious person [ie parson], who liv’d a Hermit here. (Camden 1438-1438)

The Welsh scholar William Baxter concurred:

Adros, in Pliny written corruptly Andros, whilst in many manuscripts of Ptolemy it is Ἀδρου ἐρημος, or desert of Adrus, and given incorrectly in the majority of them as Ἐδρου. This is an island in the Vergivian Sea with today the same meaning, the Island of Birds, or known in English as Birdsey. The Romans seem to have used Adros as an abbreviation for Adar inis: as Adar means Birds in Britannic ... Island was inis among the Britons, and ey amongs the ancient Saxons. (Baxter 7)

John Ware and Walter Harris took issue with Camden:

EDRI, an Island: Called by Pliny, Andros [and Adros, as some Copies have it] and is placed by Ptolomey among those Islands which lie off the East of Ireland. I take it to be the same with that Island which we call Beg-eri, or Little-Ireland, and lies off the mouth of the River Slain [Slaney] in the County of Wexford. Camden will have it to be Berdsey or Enbly, which belongs to Caernarvon-shire in Wales, and reasons, that Ader in British signifies a Bird, from whence the English in the same Sense call it Berdsey, [or the Island of Birds.] But I think he is mistaken. (Ware & Harris 40)

Beggarin Island, or Little Ireland, was an island in the northern part of Wexford Harbour. It is now part of the Wexford Slobs, and is not really an island anymore. It seems a bizarre candidate for Ptolemy’s Adros. Nevertheless, in 1789, William Beauford was happy to write:

This is called by Pliny Andros, and by Ware is justly supposed to be Beg Eri on the coast of Wexford. (Beauford 72)

The German geographer Konrad Mannert and the French geographer Pascal-François-Joseph Gosselin identified Ptolemy’s Adros with Lambay Island, which lies off the coast of north County Dublin (Mannert 229-230, Gosselin 227).

Goddard Orpen was satisfied that Ptolemy’s Adros was Howth:

Ἔδρου ἔρημος (al. Αδρου, Οδρου) is probably the present peninsula of Howth, Ir. Edar or Beann Edair, which may have been an island in Ptolemy’s time, and at any rate is joined to the mainland by such a low narrow neck of land that it may well have been mistaken for an island. It appears to be called Andros (al. Edros) by Pliny. (Orpen 128)

The local Irish historian John D’Alton identified it with Ireland’s Eye, a small island that lies immediately to the north of Howth (D’Alton 166). Several other scholars also opted for Ireland’s Eye, probably because it was at least an actual island, unlike Howth.

André Berthelot followed the map of the Brabantian cartographer Abraham Ortelius:

Adros and Limnos, “deserted”, the first off the coast of Eblana, the second off the coast of the Oboka, seem to us to designate the uninhabitable shallows, which were probably uncovered in those days during low tide: the Kish Bank or the Codling Bank and the Arklow Bank. This is the interpretation on Ortelius’s map, the only interpretation compatible with Ptolemy’s coordinates. (Berthelot 247)

On Abraham Ortelius’s 1608 map of Ireland, these three banks are displayed with the names: North Groundes, Midell Groundes, and South Groundes. On his earlier map of 1592, they appear as actual offshore islands.

Much more recently, Louis Francis has suggested that Ptolemy’s Edra and Limnos ... could be Jura and Islay (Francis Section 2).

Roman Era Names

The etymologists at Roman Era Names simply ignore all the foregoing scholarship and declare ex cathedra that Ptolemy’s Edru refers to Lambay Island. They also suggest an Indo-European etymology for this toponym:

Εδρου (or Αδρου) νισος [sic] (Edru 2,2,12) was Lambay island, near Loughshinny, for which it would have been a good navigation marker. PIE *sed- ‘to sit, settle’ had descendants in many languages, including Greek ἑδρα (hedra) ‘sitting place’ whose many specific uses included ‘base for ships’.

These experts also equate Pliny’s Andros and Ptolemy’s Edru, and suggest the following alternative etymology:

Andros

Attested: Pliny 4,16 reeled off a list of Britain’s lesser islands, including Mona, Monapia, Riginia, Vectis, Silumnus, and Andros, which were inter Hiberniam ac Britanniam ‘between Ireland and Britain’.Where: Bardsey Island, off the Lleyn Peninsula of north-west Wales, was suggested by William Camden in about 1600, and is often repeated, but really there is no strong reason why it could not be a dozen other islands (Lundy, Skomer, Caldey, Ramsey, Walney, etc). Possibly more likely is Εδρου or Αδρου island of Ptolemy (discussed under Ireland), which was probably Lambay island, near the large headland fort at Drumanagh, north of Dublin.

Name origin: Greek ανδρος was the genitive of ανηρ ‘man’ and Andros was an important Greek island. If that was distorted from εδρα that would fit Lambay. (Roman Era Names)

Conclusion

In my opinion, Ptolemy’s Adros refers to the peninsula of Howth, which is only connected to the mainland by a narrow isthmus or tombolo at Sutton. Furthermore, Ptolemy’s spelling of the name postdates Pliny’s spelling of the name, confirming my suspicion that Ptolemy’s source for his nine “Irish” islands was a contemporary one, unlike his principal source for the mainland features of Ireland.

References

- William Baxter, Glossarium Antiquitatum Britannicarum, sive Syllabus Etymologicus Antiquitatum Veteris Britanniae atque Iberniae temporibus Romanorum, Second Edition, London (1733)

- William Beauford, Letter from Mr. William Beauford, A.B. to the Rev. George Graydon, LL.B. Secretary to the Committee of Antiquities, Royal Irish Academy, The Transactions of the Royal Irish Academy, Volume 3, pp 51-73, Royal Irish Academy, Dublin (1789)

- André Berthelot, L’Irlande de Ptolémée, in Revue Celtique, Volume 50, pp 238-247, Librairie Ancienne Honoré Champion, Paris (1933)

- William Camden, Britannia: Or A Chorographical Description of Great Britain and Ireland, Together with the Adjacent Islands, Second Edition, Volume 2, Edmund Gibson, London (1722)

- John D’Alton, The History of the County of Dublin, Hodges and Smith, Dublin, (1838)

- Louis Francis (editor, translator), Geographia: Selections, English, University of Oxford Text Archive (1995)

- James Fraser, Irish Aru “Aran”, Revue Celtique, Volume 39, pp 353-354, F Vieweg, Paris (1922)

- Pascal-François-Joseph Gosselin, Recherches sur la Géographie Systématique et Positive des Anciens pour Servir de Base à l’Histoire de la Géographie Ancienne, Volume 4, L’Imprimerie Impériale, Paris (1813)

- Amalia E Gnanadesikan, The Writing Revolution: Cuneiform to the Internet, Blackwell Publishing, John Wiley & Sons, Ltd, Chichester (2009)

- Alfred Holder, Alt-Celtischer Sprachschatz, Volume 1, Druck und Verlag von B G Teubner, Leipzig (1896)

- Patrick Weston Joyce, The Origin and History of Irish Names of Places, Volume 1, Longmans, Green, & Co, London (1910)

- Henry George Liddell, Robert Scott, A Greek-English Lexicon, Eighth Edition, American Book Company, New York (1901)

- Alexander MacBain, Ptolemy’s Geography of Scotland, Eneas Mackay, Stirling (1911)

- Konrad Mannert, Geographie der Griechen und Römer: Britannia, Hahnsche Buchhandlung, Leipzig (1822)

- Karl Wilhelm Ludwig Müller (editor & translator), Klaudiou Ptolemaiou Geographike Hyphegesis (Claudii Ptolemæi Geographia), Volume 1, Alfredo Firmin Didot, Paris (1883)

- Karl Friedrich August Nobbe, Claudii Ptolemaei Geographia, Volume 1, Karl Tauchnitz, Leipzig (1845)

- Karl Friedrich August Nobbe, Claudii Ptolemaei Geographia, Volume 2, Karl Tauchnitz, Leipzig (1845)

- Charles O’Conor, Rerum Hibernicarum Scriptores Veteres, Volume 1, Prolegomena, Pars I, John Seeley, Buckingham (1814)

- Thomas F O’Rahilly, Early Irish History and Mythology, Dublin Institute for Advanced Studies, Dublin (1946, 1984)

- Goddard H Orpen, Ptolemy’s Map of Ireland, The Journal of the Royal Society of Antiquaries of Ireland, Volume 4 (Fifth Series), Volume 24 (Consecutive Series), pp 115-128, Dublin (1894)

- Holger Pedersen, Vergleichende Grammatik der Keltischen Sprachen, Volume 1, Vandenhoeck und Ruprecht, Göttingen (1909)

- Pliny the Elder, John Bostock, Henry Thomas Riley, The Natural History of Pliny, Volume 1, Henry G Bohn, London (1855)

- Julius Pokorny, Die Insel Arran und der Hügel von Howth [The Isle of Arran and the Hill of Howth], in Zeitschrift für Celtische Philologie, Volume 15, pp 193-196, (1925)

- Julius Pokorny, Indogermanisches Etymologisches Wörterbuch, Volume 1, A Francke, Bern (1959)

- Julius Pokorny, Indo-European Etymological Dictionary, Internet Archive, Opensource (2007)

- Claudius Ptolemaeus, Geography, Biblioteca Apostolica Vaticana, Vat Gr 191, fol 127-172 (Ireland: 138v–139r)

- F E Romer, Pomponius Mela’s Description of the World, The University of Michigan Press, Ann Arbor MI (1998)

- Herbert Weir Smyth, A Greek Grammar for Colleges, American Book Company, New York (1920)

- Rudolf Thurneysen, Osborn Bergin (translator), D A Binchy (translator), A Grammar of Old Irish, Translated from Handbuch des Altirischen (1909), Dublin Institute for Advanced Studies, Dublin (1946, 1998)

- James Ware, Walter Harris (editor), The Whole Works of Sir James Ware, Volume 2, Walter Harris, Dublin (1745)

- Friedrich Wilhelm Wilberg, Claudii Ptolemaei Geographiae, Libri Octo: Graece et Latine ad Codicum Manu Scriptorum Fidem Edidit Frid. Guil. Wilberg, Essendiae Sumptibus et Typis G.D. Baedeker, Essen (1838)

- Jens Jacob Asmussen Worsae, An Account of the Danes and the Norsemen in England, Scotland and Ireland John Murray, London (1852)

Image Credits

- Ptolemy’s Map of Ireland: Wikimedia Commons, Nicholaus Germanus (cartographer), Public Domain

- Greek Letters: Wikimedia Commons, Future Perfect at Sunrise (artist), Public Domain

- T F O’Rahilly: Copyright Unknown, Fair Use

- Howth (Édar): © An Garda Síochána, Fair Use

- Bardsey Island, Wales: Coflein, Crown Copyright, Non-commercial Government Licence 1.0

- Beggarin Island (North Slob): Ask About Ireland, Fair Use

- Abraham Ortelius’s Map of Ireland (Detail): Abraham Ortelius (cartographer), Theatrum Orbis Terrarum, London (1608) Public Domain

- Lambay Island: © Joseph Mischyshyn, Creative Commons License

- The Peninsula of Howth: © Ronan Purcell, Fair Use