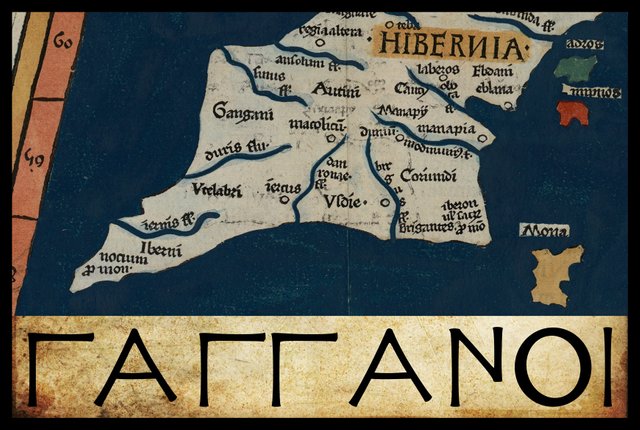

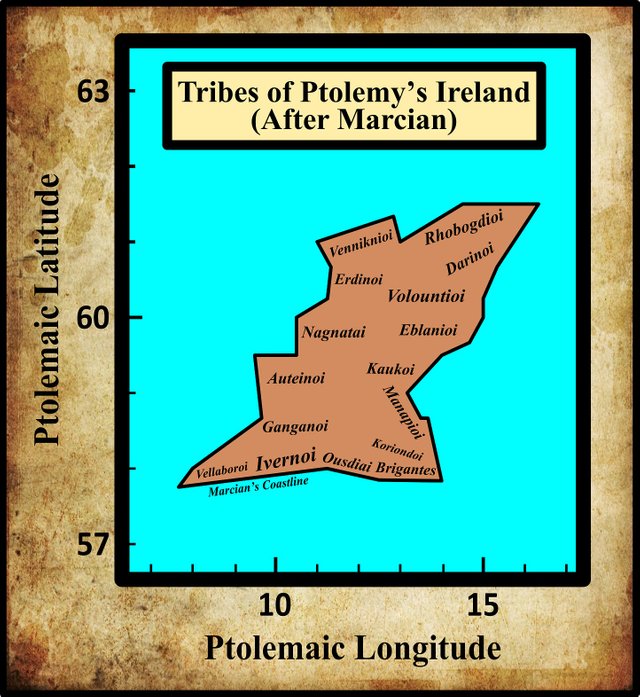

In his description of Ireland, Geography 2:2 §§ 1-10, Claudius Ptolemy records the disposition of sixteen Irish tribes. Resuming our voyage down the west coast of the island, the thirteenth people to be encountered are the Ganganoi (Latin: Gangani). Ptolemy places these immediately south of the Auteinoi.

In his 1883 edition of the Geography, Karl Müller records only a single variant reading of this ethnonym, but it differs from the critical form only in its application of the Greek accents. As the use of these accents was not regularized until the Byzantine era, they are generally considered to be “without authority” (O’Rahilly 1 fn 2, Gnanadesikan 220-221). In his 1838 edition of Ptolemy’s Geography, Friedrich Wilberg also records the same variant reading as Müller.

Identity

Whoever the Ganganoi were, it is possible that a branch of them also dwelt in western Britain. Müller notes:

Cf. Γαγγανῶν ἄκρον [Ganganōn akron = Promontory of the Ganganoi], which according to several codices was on the western shore of Britain (see below, chapter 3 § 2). The Gangani are thought to have dwelt on the Senus, or River Shannon. (Müller 77)

In 1:3 § 2 of the Geography, which describes the western coast of Britain, there is a promontory called—in Müller’s edition—Καιαγγανων ακρον [Promontory of the Kaianganoi]. This is usually identified with the Llŷn Peninsula in the northwest of Wales. Müller notes that this reads Γαγγανῶν ἄκρον [Promontory of the Ganganoi] in nine early sources. Müller, however, believes that the critical form that he gives is the correct form, even though it only occurs in a single manuscript (Vaticanus 191), as it tallies with other primary sources (Müller 85):

- Tacitus’ Annals 12:32.

- The anonymous Ravenna Cosmography.

- Roman inscriptions from the time of Vespasian and Domitian .

Wilberg, however, has chosen Γαγγανῶν ἄκρον as the critical form in his edition of the Geography—presumably because it is the commonest reading. In his edition of 1845, Karl Nobbe also opts for Γαγγανῶν ἄκρον as the critical form (Nobbe 68).

Writing about a decade after Müller, the Irish historian Goddard Orpen remarks:

With the Γαγγανοί [Ganganoi], placed near the Shannon, we may compare the Γαγγανῶν ἄκρον [Promontory of the Ganganoi] (according to the ordinary reading) of modern Carnarvonshire. Perhaps we may look upon the legendary Gann as the eponymous ancestor of the Gangani. The name occurs under the forms Gann and Genann, as chiefs of the Fomori, and under those of Gann, Genann, and Sengann, as leaders of the Firbolg, to the two latter of whom the districts on each side of the Shannon are traditionally assigned. (Orpen 119)

This is an intriguing idea. According to The Book of Invasions, when the Fir Bolg (Belgae Celts) invaded Ireland, they divided it into five provinces amongst the five sons of Dela (Macalister 7). Roderic O’Flaherty summarizes this as follows in his Ogygia:

The Belgians, from Great Britain, planted the third colony in Ireland. Their leaders being Slangy, Rudric, Sengann, Ganann [Genann] and Gann, the five sons of Dela, the son of Loich ... They divided the island between them, having distributed it into five portions ... Desmond is possessed by Gann, from the confluence of the three rivers to Belach-conglais, near Cork, afterwards the province of South-Munster, belonging to Achy Abratruaidh. Sengann obtains North-Munster, from that to Ros-da-shailech, where Limerick now stands, which is denominated the province of Curo, the son of Daire; and Ganann assumes the supremacy of Connaught, extending from the above-mentioned city to the river Droby. (O’Flaherty 14-15)

Two of these regions, those of Sengann (West Munster) and Genann (Connacht), do correspond roughly to the territory of Ptolemy’s Ganganoi. Is this a coincidence?

T F O’Rahilly, however, does not even mention this hypothesis let alone refute it. He was, nevertheless, aware of it, as Orpen’s paper was one of his sources (O’Rahilly 1 fn 2). Instead, he restricts himself to the following brief comment:

Gangani. These were probably located near the mouth of the Shannon. No trace of their name has survived in Irish; but there appears to have been a tribe of the same name in North-West Wales, for Ptolemy calls the extreme point of the Lleyn Peninsula, in Caernarvonshire, Γαγγανῶν ἄκρον, ‘the headland of the Gangani’. (O’Rahilly 10)

The etymologists at Roman Era Names have offered a plethora of possible origins for this ethnonym, and have also breathed new life into an old Iberian hypothesis first mooted by William Camden in the 16th century (see below):

Γαγγανοι (Ganganoi 2,2,5) lived in the south-west, probably around the mouth of the Shannon. See the discussion of Γαγγανων ακρον in Wales.

Following their link, we read:

The Llŷn peninsula of north Wales, with its western tip at Braich y Pwll, SH135256, is the “Land’s End of Wales”. It was presumably inhabited by people like those named by Ptolemy 2,2,5 as Γαγγανοι living in south-west Ireland, in modern county Clare between the Shannon and Galway Bay.

Name Origin: PIE *ghengh- ‘to go, to walk’ seems the most likely source. That root developed strongly, and close to Γαγγανοι, in Germanic languages, for example to OE gangan and to modern gangway. Celtic languages have more figurative senses, such as Welsh cangen ‘branch’ or Old Irish cingid ‘to step’ and hence words for a warrior leader as someone who strides in front. Also from that root is the Indian river name Ganga, better known (via Greek) as Ganges. Alternatively, a seaside tribe might become known from Greek γαγγαμευς ‘fisher’ and γαγγαμον ‘fishing net’ (of uncertain derivation). Or the peninsula’s shape might resemble Sanskrit jangha ‘shank’.

Notes: Many of Ptolemy’s tribal names were outsiders’ descriptions of geography or lifestyle rather than insiders’ descriptions of political units, so there is no need to postulate ... relatively recent migrations to explain why tribes in widely separate locations bore similar names. One obvious common feature of the two present regions is that they would have been settled by sea relatively soon after the last Ice Ages. If they remained culturally different from peoples to the east, as shown by their abundant megaliths, they might have become described as ‘gone away’ people. That hypothesis might also fit the Koncani of Goa, India, and the Concani of northern Spain. (Roman Era Names)

The independent researcher Martin Counihan has taken the liberty of emending this ethnonym to Galengani:

To the north of the Vellabori Ptolemy placed a tribe whom he called the Gangani. Their name has been difficult for scholars to interpret. Part of the problem is that, in his account of Britain, Ptolemy refers to the Lleyn peninsula in Wales as Ganganorum Promontorium, the promontory of the Gangani. So, did the Gangani own land both in the west of Ireland and in Wales? Or were the Gangani a purely Welsh tribe, with their attribution to Ireland being due to a misunderstanding or mistake in the data which had been passed to Ptolemy? The most plausible explanation is that the Gangani dwelt exactly where Ptolemy said they did, in Ireland, and that the ancient mistake was to place their promontory in Britain. So, in reality, Ganganorum Promontorium was in the west of Ireland, and can be identified with Loop Head in County Clare—the same promontory, jutting out towards Spain, which Orosius considered noteworthy.

Another part of the problem is that Gangani, as it stands, lacks any clear meaning. The solution is to suppose that the correct form of the name was Galengani, and that Gangani was arrived at by the loss of the second syllable—the process known in linguistics as syncope. Galengani strongly suggests an identification with a well-attested ancient Irish group, the Gailenga. This is confirmed by Irish tradition according to which the Luigni and the Gailenga were originally neighbours in north Munster. In fact, the ancestry of the Luigni included the mythological eponym of the Gailenga, Cormac Gaileng. It is compelling to conclude that Orosius’ Luceni and Ptolemy’s Gangani/Galengani were both to be found in County Clare on the northern side of the Shannon estuary. The Old Irish word for a spear, gáe, is the root of the tribal name Gailenga. They were “the spearmen”. Later in their history the Gailenga, alongside their cousins the Luigni, evidently moved to the north, and their name was eventually given to the barony of Gallen in County Mayo. (Counihan 10-11)

This is all very speculative. Paulus Orosius, writing in the early 5th century, does refer to the headland “where the mouth of the Scena River is found” (Orosius 1:2), but as he also claims that Brigantia in the northwest of Iberia “is most clearly visible from that promontory”, he is probably thinking of one of the headlands in County Kerry. Nevertheless Loop Head is perhaps significant enough to have merited inclusion in Ptolemy’s Geography. But what about Braich y Pwll, the headland at the end of Llŷn Peninsula? If we transfer Γαγγανων ακρον to Loop Head, then there is no mention of Braich y Pwll. Ptolemy is more likely to have omitted the former than the latter. His description of Britain is vastly more detailed than his sparse description of Ireland. On the other hand, Ptolemy does not include any Ganganoi among the tribes of Britain, which suggests that the promontory has indeed been misplaced.

Another problem with Counihan’s analysis is that the Gailenga were probably a branch of the Lagin or Dumnonii, who are not mentioned at all in Ptolemy’s description of Ireland—though they do appear in his description of Britain. O’Rahilly concludes from this that Ptolemy’s information about Ireland was drawn from very old sources that predated the Laginian invasion, such as the lost work of Pytheas of Massalia, who visited these islands around 325 BCE. O’Rahilly places the Laginian invasion some time in the third century BCE (O’Rahilly 22-23, 39-42, 92-146). Of course, O’Rahilly may be mistaken regarding the ethnic provenance of the Gailenga, so Counihan’s hypothesis deserves to be borne in mind.

Earlier Scholarship

The English antiquary William Camden believed that the Ganganoi were of Iberian origin. In his description of the western province of Connacht, he wrote:

Antiently, as appears from Ptolemy, the Gangani, otherwise called the Concani, Auteri, and Nagnatæ, dwelt here. These Concani or Gangani (descended, like the Luceni, their neighbours, from the Lucensii of Spain) are probably, from the affinity and nearness both of names and places, deriv’d from the Concani of Spain, who in different copies of Strabo are writ Coniaci, and Conisci : These were originally Scythians, and drank the blood of horses, as Silius tells us : a thing not unusual heretofore among the wild Irish ... Unless Conaughty, the Irish name, may be thought to be a compound of Concani and Nagnatæ. (Camden 1377-1378)

The Irish antiquary James Ware made note of this, adding only that the Ganganoi “inhabited Thuomond and some of the southern Parts of the County of Galway” (Ware & Harris 40). Even as late as the 19th century, Camden’s hypothesis was accepted by Fr Charles O’Conor (O’Conor li).

The Welsh scholar William Baxter anticipated Karl Müller’s analysis. In his Glossarium, under the heading Gangani, he referred the reader to another Celtic tribe, the Ceangi. The latter merited one of Baxter’s longest entries, running to over three pages. Briefly, he identified the Irish Ceangi as Fir Domnainn or Dumnonii (Laginians), believing them to be a colony of British Dumnonians from Somerset (Baxter 74).

William Beauford devised a unique and fanciful etymology of this ethnonym, which led him to place them in Connemara, in the western part of County Galway:

Γαγγανοι. Ware thinks them the ancient inhabitants of the southern parts of the county of Galway. The Romans do not seem to have obtained the real name of these people, but, as in other instances, to have denominated them from their principal headland, in Irish Cean Gibhne, pronounced Kan Ganné, that is Dog’s Head, still retaining its ancient name. They were therefore the ancient inhabitants of Conmacnemarra in that county. (Beauford 60)

Conclusions

Ptolemy’s Ganganoi dwelt, apparently, near the mouth of the River Shannon—either in County Clare, on the right bank of the river, or in County Limerick, on the left bank. They were probably a Belgic tribe, with just the slightest possibility that their name is related to that of one of the legendary leaders of the Fir Bolg. It is, however, more likely that they were simply a Celtic people whose identity and independence were lost before the start of our written history—possibly during the Laginian or the Goidelic conquest of Connacht (O’Rahilly 141-146, 173).

References

- William Baxter, Glossarium Antiquitatum Britannicarum, sive Syllabus Etymologicus Antiquitatum Veteris Britanniae atque Iberniae temporibus Romanorum, Second Edition, London (1733)

- William Beauford, Letter from Mr. William Beauford, A.B. to the Rev. George Graydon, LL.B. Secretary to the Committee of Antiquities, Royal Irish Academy, The Transactions of the Royal Irish Academy, Volume 3, pp 51-73, Royal Irish Academy, Dublin (1789)

- William Camden, Britannia: Or A Chorographical Description of Great Britain and Ireland, Together with the Adjacent Islands, Second Edition, Volume 2, Edmund Gibson, London (1722)

- Martin Counihan, Researchgate (2019)

- Amalia E Gnanadesikan, The Writing Revolution: Cuneiform to the Internet, Blackwell Publishing, John Wiley & Sons, Ltd, Chichester (2009)

- Ernst Willibald Emil Hübner (editor), Corpus Inscriptionum Latinarum, Volume 7, Inscriptiones Britanniae Latinae, Numbers 1205-1206, Berlin-Brandenburg Academy of Sciences and Humanities, Georg Reimer, Berlin (1873)

- R A Stewart Macalister (editor & translator), Lebor Gabála Érenn: The Book of the Taking of Ireland, Part 4, Irish Texts Society, Volume 41, The Educational Company of Ireland, Ltd, Dublin (1941)

- Karl Wilhelm Ludwig Müller (editor & translator), Klaudiou Ptolemaiou Geographike Hyphegesis (Claudii Ptolemæi Geographia), Volume 1, Alfredo Firmin Didot, Paris (1883)

- Karl Friedrich August Nobbe, Claudii Ptolemaei Geographia, Volume 1, Karl Tauchnitz, Leipzig (1845)

- Karl Friedrich August Nobbe, Claudii Ptolemaei Geographia, Volume 2, Karl Tauchnitz, Leipzig (1845)

- Charles O’Conor, Rerum Hibernicarum Scriptores Veteres, Volume 1, Prolegomena, Pars I, John Seeley, Buckingham (1814)

- Roderic O’Flaherty, James Hely (translator), Ogygia, Or, A Chronological Account of Irish Events, Volume 2, W McKenzie, Dublin (1793)

- Thomas F O’Rahilly, Early Irish History and Mythology, Dublin Institute for Advanced Studies, Dublin (1946, 1984)

- Paulus Orosius, Seven Books of History Against the Pagans, R P Pryne, Toronto (2015)

- Goddard H Orpen, Ptolemy’s Map of Ireland, The Journal of the Royal Society of Antiquaries of Ireland, Volume 4 (Fifth Series), Volume 24 (Consecutive Series), pp 115-128, Dublin (1894)

- Moritz Pinder, Gustav Parthey (editors), Ravennatis Anonymi Cosmographia et Gvidonis Geographica [The Cosmography of the Anonymous of Ravenna and the Geography of Guido of Pisa], Friedrich Nicolai, Berlin (1860)

- Claudius Ptolemaeus, Geography, Biblioteca Apostolica Vaticana, Vat Gr 191, fol 127-172 (Ireland: 138v–139r)

- Silius Italicus, James Duff Duff (translator), Punica, Volume 1, Loeb Classical Library L277, Harvard University Press, Cambridge MA (1927, 1961)

- Tacitus, The Annals and History of Tacitus: A New and Literal English Version, D A Talboys, Oxford (1839)

- James Ware, Walter Harris (editor), The Whole Works of Sir James Ware, Volume 2, Walter Harris, Dublin (1745)

- Friedrich Wilhelm Wilberg, Claudii Ptolemaei Geographiae, Libri Octo: Graece et Latine ad Codicum Manu Scriptorum Fidem Edidit Frid. Guil. Wilberg, Essendiae Sumptibus et Typis G.D. Baedeker, Essen (1838)

Image Credits

- Ptolemy’s Map of Ireland: Wikimedia Commons, Nicholaus Germanus (cartographer), Public Domain

- Greek Letters: Wikimedia Commons, Future Perfect at Sunrise (artist), Public Domain

- Llŷn Peninsula, Wales: Wikimedia Commons, Creative Commons License

- T F O’Rahilly: Copyright Unknown, Fair Use

- Loop Head, County Clare: © Tourism Ireland, Fair Use

- Connemara, County Galway: © Calum Hutchinson, Creative Commons License

- The Cliffs of Moher, County Clare: © EliziR, Creative Commons License