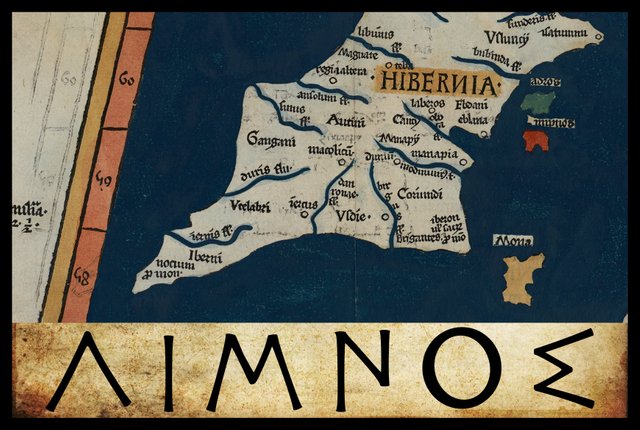

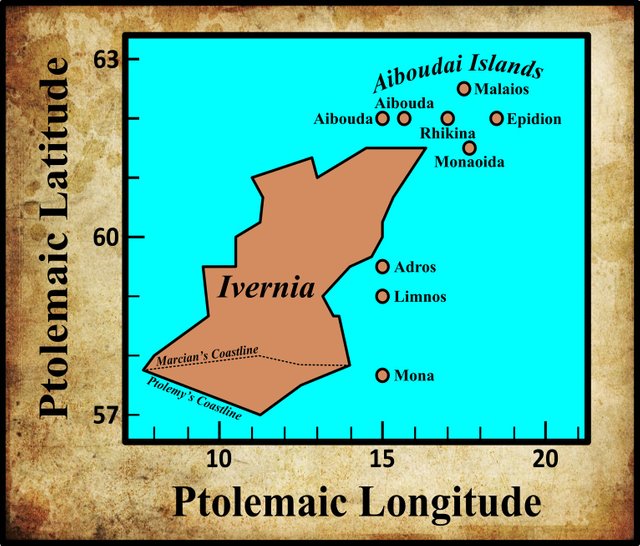

In the final section of his description of Ireland—Geography, Book 2, Chapter 2, § 10—Claudius Ptolemy records the names and coordinates of nine islands, five of which lie to the north of Ireland and four to the east. The last of the four eastern islands is called Λιμνου ἐρημος [The Desert Island of Limnos].

In his 1883 edition of the Geography, Karl Müller records only a single variant reading of this toponym. Friedrich Wilberg records this same variant in his 1838 edition of the Geography.

| Source | Greek | English |

|---|---|---|

| Most MSS | Λιμνου | Limnou |

| B, E, L2, Z | Λίνου | Linou |

B and E are two of the Codices Parisini Graeci in the Bibliothèque nationale de France in Paris: Grec 1404 and Grec 1403 respectively.

L2 is a manuscript from the library at Vatopedi, the ancient monastery on Mount Athos in Greece. Müller makes a distinction between L and L2, but he never clarifies what this distinction entails.

Z is Vaticanus Palatinus Graecus 314, a Greek manuscript from the old Palatinate Library of Heidelberg, which is now part of the Vatican Library in Rome. In addition to B and E, Wilberg also attributes this variant to Pal. 1, which possibly refers to this manuscript.

It is curious that these four manuscripts are the same ones that record the variant reading Ὄδρου [Odrou] for Ἄδρου [Adrou] in the name of the preceding island. Perhaps this means that these manuscripts were copied from a common original. It is probably safe to dismiss this reading as a simple typographical error.

The name of this island, like that of its immediate predecessor, is qualified with the adjective ἐρημος [erēmos]:

ἐρημος Desolate, lonely, lonesome, solitary ... (Liddell & Scott 577)

Presumably, this means that these two islands were uninhabited. ἐρημος, I take it, stands for νησος ἐρημος, desert island. Note that while νησος [nēsos], island, is a feminine noun, it was common practice to qualify it with the masculine form of the adjective (Smyth 74).

Λιμνου [Limnou] is clearly the genitive case of Λιμνος [Limnos]. Λιμνου ἐρημος means: Desert Island of Limnos. Müller seems to imply that this is the case by identifying this island with a similarly named island mentioned in the Natural History of Pliny the Elder:

Lumnus (codex A) or Silumnus (codices R and D) in Pliny [4:30]; perhaps Linnonsa in the Ravenna Cosmography (1:50). (Müller 81)

As we have already seen, Pliny gives a list of islands off the shores of Britain and Ireland:

This last island [Hibernia] is situate beyond Britannia ... Of the remaining islands none is said to have a greater circumference than 125 miles [200 km]. Among these there are the Orcades, forty in number, and situate within a short distance of each other, the seven islands called Acmodæ, the Hæbudes, thirty in number, and, between Hibernia and Britannia, the islands of Mona, Monapia, Ricina, Vectis, Limnus, and Andros. (Pliny 351)

Here, Limnus (Lumnus, Silumnus, Silimnus) surely refers to the same island as Ptolemy’s Limnou erēmos, confirming that the correct form of the name is Limnos.

The Ravenna Cosmography, an anonymous collection of toponyms compiled at the beginning of the 8th century, includes the following:

Similarly, in that western Ocean are located several islands, some of which we will name, to wit: Corsula, Mona, Regaina, Minervae, Cunis, Manna, Botis, Vinios, Saponis, Susura, Birila, Elaviana, Sobrica, Scetis, Linnonsa [Linonsa] (Pinder et al 440-441)

In his analysis of this section of the Cosmography, Keith Fitzpatrick-Matthews identifies Scetis [Scitis] with the Scottish Isle of Skye, which leads him to suggest a novel candidate for Linnonsa:

<Linnonsa> may be an error for *Limnus insula, although it is not necessarily the same as the Λίμνου ἔρημος of Ptolemy (II.2, 10), which is identified with Lambay. Working backwards from Scitis, Skye ... The name which follows Skye, *Limnus Insula, could be the island of Raasay, to the north. With so obscure a list, there can be no certainty. (Fitzpatrick-Matthews 81)

Identity

Having identified Ptolemy’s Adros with Ireland’s Eye, a small island off the north coast of Howth, Karl Müller was satisfied that Limnus referred to Lambay Island, a somewhat larger island about 9 km to the north of Ireland’s Eye. Ptolemy, however, places Limnus half a degree south of Adros in latitude 59° (in the same longitude of 15°), but Muller was sufficiently confident of his identification to emend Ptolemy’s coordinates:

Adros, lying adjacent to Eblana, is a small island which is called Ireland’s Eye. Nearly 60 stadia [~9 km] to the north of this, Lambey island appears to be Limnu, so much so that it might have been recorded before the island of Adru in the following manner:

| Λιμνου [Limnou] | 59° 35' |

|---|---|

| Ἄδρου [Adrou] | 59° 30' |

(Müller 81)

Henry Bradley also noted the unhelpful order in Ptolemy:

The other uninhabited island off this coast, Limnus, may perhaps be Lambay, although in that case the relative situations of Edrus and Limnus have been reversed. (Bradley 396)

Lambay has been a popular choice for Limnos over the centuries. It should be noted, however, that the modern name is of Old Norse origin, meaning Lamb Island. It cannot possibly have any connection with Ptolemy’s Limnos. Furthermore, if Limnos does refer to Lambay, then that must be an old name for the island that had fallen out of use at an early date. In our native records, the island was known as Rechru, a name it shared with Rathlin Island off the coast of County Antrim:

Lambay is merely an altered form of Lamb-ey, i.e. Lamb-island; a name which no doubt originated in the practice of sending over sheep from the mainland in the spring, and allowing them to yean on the island, and remain there, lambs and all, during the summer. Its ancient Irish name was Rechru, which is the form used by Adamnan, as well as in the oldest Irish documents; but in later authorities it is written Rechra and Reachra. (Joyce 111)

The temptation to identify Limnos with Lambay has proved too great for some scholars. It is even possible that some of those who know better suspect that there is an etymological connection. Perhaps the Vikings called it Lambay because it was referred to locally by a similar-sounding name? But no such name is known to history.

Roman Era Names

As usual, the experts at Roman Era Names have gone their own way, suggesting a Greek etymology for the name and identifying it with the Nose of Howth:

Λιμνου νησος (Limnu 2,2,12) was an island south of Εδρου [Edrou] and close to Dublin. It has been identified with Dalkey island, which is tiny, as is Ireland’s Eye, but it is probably better to guess that the Nose of Howth peninsula was at least a tidal island in Ptolemy’s day. The name is much more likely to derive from Greek λιμην [limēn] ‘harbour’ than from Celtic words for ‘smooth’ or ‘elm’. (Roman Era Names)

The Nose of Howth is a rocky promontory in the northeastern corner of the Howth Peninsula. It was certainly not a tidal island in Ptolemy’s day. Perhaps they are referring to another feature on the peninsula.

Early Scholarship

In the 16th century, the English antiquary William Camden suggested that Ptolemy’s Limnos referred to Ramsey Island off the southwest coast of Wales:

I was heretofore of Opinion, that this Scalemy was the Silimnus of Pliny; but since, I have had reason to be of another mind. For the Silimnus in Pliny may probably, from the resemblance of the two names, be the Limni in Ptolemy. That this Limni is the same which the Britains call’d Lymen, is clear from the name it self, tho’ the English have given it another, viz. that of Ramsey. It lies over-against the episcopal See of St. David, to which it belongs; and was famous in the last age for the death of Justinian a holy man ... In the history of his life, this Island is often call’d Insula Lemeneia. (Camden 1438)

William Baxter agreed with Camden, adding a fanciful Celtic etymology of his own, which would derive Limen from Liv Inis, or Island in the Flood (Baxter 152-153).

The Irish antiquary James Ware was aware of the Norse etymology of Lambay, but was still seduced by the similarity between the modern name of this island and Ptolemy’s Limni:

Limni, an Island. Now Lambay, an Island near the Shore belonging to the County of Dublin; and this seems to be pointed out both by the Name, and by the Situation given to it by Ptolemy. Camden makes it the Island of Ramsey in Pembroke-shire in Wales. The Exposition of Lambay is the Isle of Lambs, as Ramsey is the isle of Rams, and Shepey in Kent, the isle of Sheep. (Ware & Harris 41)

Eilert Ekwall derives the toponym Ramsey from the Old English: Hramsa, ramson, wild garlic (Ekwall 362, 243).

In the late 18th century, the Irish scholar William Beauford accepted Ware’s identification, another victim of the coincidental similarity between Limnos and Lambay:

Ware justly supposes this to be Lambey on the coast of the county of Dublin. (Beauford 72)

A quarter of a century later, another Irish scholar, Fr Charles O’Conor, repeated this claim (O’Conor lvi).

Goddard Orpen, writing near the end of the 19th century, was one of the first Irish scholars to reject the identity of Ptolemy’s Limnos and Lambay Island:

What Λίμνου ἐρημος represents is more doubtful. from its position it cannot be Lambay, which, too, is probably a Norse name. It may possibly be Dalkey Island, as Ptolemy frequently places his islands much too far from the mainland. It is evidently the Limnus of Pliny. (Orpen 128)

As we saw in the preceding article in this series, the French scholar André Berthelot identified the two uninhabited islands of Adros and Limnos with sandbanks off the east coast of Ireland:

Adros and Limnos, “deserted”, the first off the coast of Eblana, the second off the coast of the Oboka, seem to us to designate the uninhabitable shallows, which were probably uncovered in those days during low tide: the Kish Bank or the Codling Bank and the Arklow Bank. This is the interpretation on Ortelius’s map, the only interpretation compatible with Ptolemy’s coordinates. (Berthelot 247)

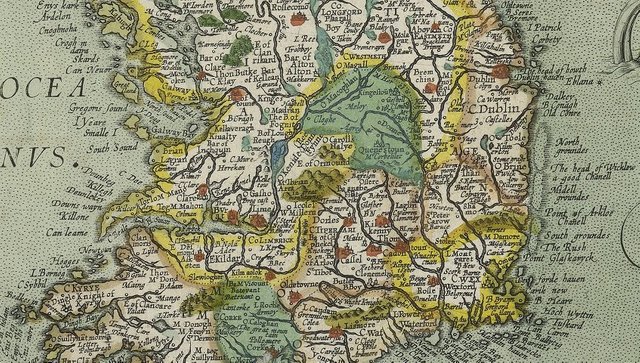

On Abraham Ortelius’s 1608 map of Ireland, these three banks are displayed with the names: North Groundes, Midell Groundes, and South Groundes. On his earlier map of 1592, they appear as actual offshore islands.

We also saw in the preceding article that Louis Francis identified these two islands with Jura and Islay in the Scottish Hebrides (Francis Section 2).

Conclusions

As we have already seen, the nine islands that Ptolemy categorized as Irish actually comprise a list of islands that lay to the west of Britain. Some of them undoubtedly belong to Britain rather than to Ireland. There is, therefore, no particular reason why Limnos should be Lambay Island rather than, say, Raasay or Ramsey—or Lundy, for that matter. The old name of Ramsey Island, however, may preserve a trace of Ptolemy’s Limnos. To my mind that carries more weight than the fact that Ptolemy assigned these nine islands to Ireland.

References

- William Baxter, Glossarium Antiquitatum Britannicarum, sive Syllabus Etymologicus Antiquitatum Veteris Britanniae atque Iberniae temporibus Romanorum, Second Edition, London (1733)

- William Beauford, Letter from Mr. William Beauford, A.B. to the Rev. George Graydon, LL.B. Secretary to the Committee of Antiquities, Royal Irish Academy, The Transactions of the Royal Irish Academy, Volume 3, pp 51-73, Royal Irish Academy, Dublin (1789)

- André Berthelot, L’Irlande de Ptolémée, in Revue Celtique, Volume 50, pp 238-247, Librairie Ancienne Honoré Champion, Paris (1933)

- Henry Bradley, Ptolemy’s Geography of the British Isles, Archæologia, Volume 48, Issue 2, pp 379-396, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge (1885)

- William Camden, Britannia: Or A Chorographical Description of Great Britain and Ireland, Together with the Adjacent Islands, Second Edition, Volume 2, Edmund Gibson, London (1722)

- Eilert Ekwall, The Concise Oxford Dictionary of English Place-Names, Third Edition, Clarendon Press, Oxford (1947)

- Keith J Fitzpatrick-Matthews, Britannia in the Ravenna Cosmography: A Reassessment, Academia (2013)

- Ptolemy, Louis Francis (editor, translator), Geographia: Selections, English, University of Oxford Text Archive (1995)

- Jean Hardouin, Caii Plinii Secundi Naturalis Historiae cum Interpretatione et Notis Integris, Wilhelm Gottlob Sommer, Leipzig (1778)

- Patrick Weston Joyce, The Origin and History of Irish Names of Places, Volume 1, Longmans, Green, & Co, London (1910)

- Henry George Liddell, Robert Scott, A Greek-English Lexicon, Eighth Edition, American Book Company, New York (1901)

- Karl Wilhelm Ludwig Müller (editor & translator), Klaudiou Ptolemaiou Geographike Hyphegesis (Claudii Ptolemæi Geographia), Volume 1, Alfredo Firmin Didot, Paris (1883)

- Karl Friedrich August Nobbe, Claudii Ptolemaei Geographia, Volume 1, Karl Tauchnitz, Leipzig (1845)

- Karl Friedrich August Nobbe, Claudii Ptolemaei Geographia, Volume 2, Karl Tauchnitz, Leipzig (1845)

- Charles O’Conor, Rerum Hibernicarum Scriptores Veteres, Volume 1, Prolegomena, Pars I, John Seeley, Buckingham (1814)

- Goddard H Orpen, Ptolemy’s Map of Ireland, The Journal of the Royal Society of Antiquaries of Ireland, Volume 4 (Fifth Series), Volume 24 (Consecutive Series), pp 115-128, Dublin (1894)

- Moritz Pinder, Gustav Parthey (editors), Ravennatis Anonymi Cosmographia et Gvidonis Geographica [The Cosmography of the Anonymous of Ravenna and the Geography of Guido of Pisa], Friedrich Nicolai, Berlin (1860)

- Pliny the Elder, John Bostock, Henry Thomas Riley, The Natural History of Pliny, Volume 1, Henry G Bohn, London (1855)

- Claudius Ptolemaeus, Geography, Biblioteca Apostolica Vaticana, Vat Gr 191, fol 127-172 (Ireland: 138v–139r)

- Herbert Weir Smyth, A Greek Grammar for Colleges, American Book Company, New York (1920)

- James Ware, Walter Harris (editor), The Whole Works of Sir James Ware, Volume 2, Walter Harris, Dublin (1745)

- Friedrich Wilhelm Wilberg, Claudii Ptolemaei Geographiae, Libri Octo: Graece et Latine ad Codicum Manu Scriptorum Fidem Edidit Frid. Guil. Wilberg, Essendiae Sumptibus et Typis G.D. Baedeker, Essen (1838)

Image Credits

- Ptolemy’s Map of Ireland: Wikimedia Commons, Nicholaus Germanus (cartographer), Public Domain

- Greek Letters: Wikimedia Commons, Future Perfect at Sunrise (artist), Public Domain

- Lambay Island: © Joachim S Müller, Creative Commons License

- The Nose of Howth: © Phillip Perry, Creative Commons License

- Ramsey Island: © David Wooton, Fair Use

- Dalkey Island: © Stephen Devine, Fair Use

- Abraham Ortelius’s Map of Ireland (Detail): Abraham Ortelius (cartographer), Theatrum Orbis Terrarum, London (1608) Public Domain

- Isle of Raasay: © 2019 HomeAway, Fair Use

Many times I am surprised to find well-documented academic papers on steemit. However, there are!

This post is amazing.

However, if you can suggest that I do this work in 2 parts since it is very extensive and sometimes it is difficult to read because of the slow internet connection (at least in my country).

A wonderful work like this in 2 chapters, as if it were Treasure Island, would allow you to digest reading and geographical and historical data in a more pleasant way.

It has been an honor and a pleasure to have read @harlotscurse

Downvoting a post can decrease pending rewards and make it less visible. Common reasons:

Submit

Thank you for the kind comments.

Downvoting a post can decrease pending rewards and make it less visible. Common reasons:

Submit

this is a great story! your search is full of details and valuable information !! do you do it for work or is it just a hobby for you? congratulations on your work and the curie vote

Downvoting a post can decrease pending rewards and make it less visible. Common reasons:

Submit

Just a pastime, but one I am passionate about. Thank you.

Downvoting a post can decrease pending rewards and make it less visible. Common reasons:

Submit

Hi harlotscurse,

Visit curiesteem.com or join the Curie Discord community to learn more.

Downvoting a post can decrease pending rewards and make it less visible. Common reasons:

Submit