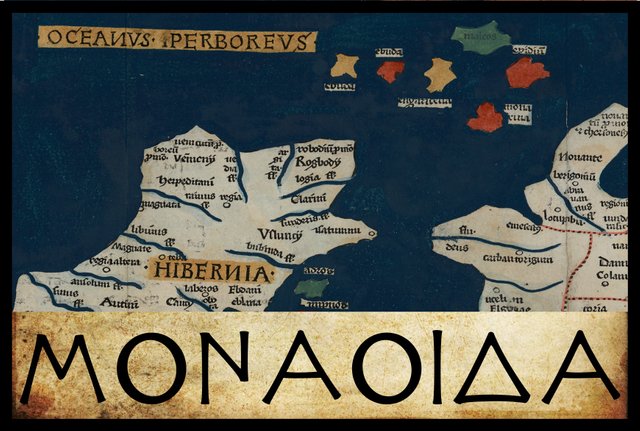

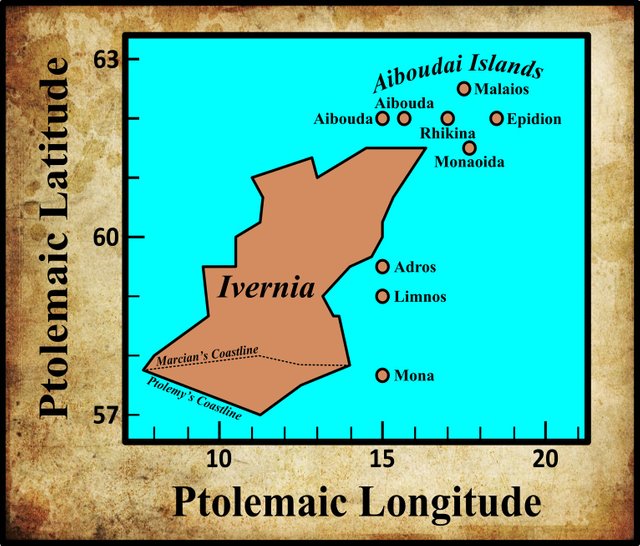

In the final section of his description of Ireland—Geography, Book 2, Chapter 2, § 10—Claudius Ptolemy records the names and coordinates of nine islands, five of which lie to the north of Ireland and four to the east. The five northern islands are called αἱ Αἰβουδαι [hai Aiboudai], and are generally identified with four of the Scottish Hebrides and Rathlin Island. The first of the four eastern islands is called Μοναοιδα [Monaoida] (Latin: Monaœda). On Ptolemy’s map, this island is quite close to the five Aiboudai and could easily be mistaken for a sixth member of that archipelago.

In his 1883 edition of the Geography, Karl Müller records one variant reading of Μοναοιδα . In his 1838 edition of the Geography, Friedrich Wilberg also records this variant, albeit from different manuscripts. In his edition of 1845, Karl Nobbe agrees with Müller and Wilberg’s critical choice.

| Source | Greek | English |

|---|---|---|

| Most MSS | Μονάοιδα | Monaoida |

| X, Σ, Φ, Ψ, Arg, Mannert, Ulm | Μοναρίνα | Monarina |

X is Vaticanus Graecus 191, which dates from about 1296. It is thought that this manuscript preserves a very ancient tradition. Ptolemy’s description of Ireland is on folia 138v and 139r.

Σ, Φ and Ψ are three manuscripts from the Laurentian Library in Florence: Florentinus Laurentianus 28, 9 : Florentinus Laurentianus 28, 38 : Florentinus Laurentianus 28, 42.

Arg is the Editio Argentinensis, which was based on Jacopo d’Angelo’s Latin translation of Ptolemy (1406) and the work of Pico della Mirandola. Many other hands also worked on it—Martin Waldseemüller, Matthias Ringmann, Jacob Eszler and Georg Übel—before it was finally published by Johann Schott in Straßburg in 1513. Argentinensis refers to Straßburg’s ancient Celtic name of Argentorate.

Mannert refers to a pair of Latin manuscripts discovered by the Prussian geographer Konrad Mannert.

Ulm is a printed edition of Ptolemy’s Geography that was published in Ulm in 1482 by Lienhart Holle, with the assistance of the cartographer Nicolaus Germanus Donis.

Isle of Man

There is a wide consensus among scholars that Ptolemy’s Monaoida refers to the Isle of Man, the large island that sits in the Irish Sea between Ireland and Britain. Several ancient sources are believed to refer to this island under a variety of similar but not identical names:

Mona, Julius Caesar, The Gallic War 5:13

Monapia, Pliny the Elder, Natural History 4:30

Evania or Mevania, Orosius, Seven Books of History Against the Pagans 1:2:82

Manna or Manua, Ravenna Cosmography 5:32

It is possible that the variant form Μοναρίνα [Monarina] arose when some helpful scribe glossed Ptolemy’s Μοναοιδα [Monaoida] as the Greek equivalent of the Latin Monapia, which was then rendered into Greek as Μοναρινα. The Greek letter rho [Ρ] is essentially identical to the Latin letter P. This explanation, however, leaves the -ν- [-n-] in Μοναρινα unaccounted for. It is also possible that the Greek Monarina was the original form, which was incorrectly transcribed into Latin as Monapia. Henry Bradley believes that both Ptolemaic forms are corruptions of Pliny’s Monapia:

There is some uncertainty as to the reading of Monaoeda. Some editions have Monarina; and Mr. Skene [Skene 69], on the evidence of the coincidence of name, identifies the island with Arran. It seems, however, probable that both Monaoeda and Monarina are corruptions of Monapia. This name, which is given by Pliny as that of an island in the Irish Sea, is the legitimate phonetic ancestor of Manaw, the Welsh name of the Isle of Man. It is more likely that Ptolemy should have omitted to mention Arran than that he should have overlooked the Isle of Man, and the situation of “Monaoeda” agrees better with the latter than with the former. Ptolemy’s Mona, placed by him near the Wexford coast, is certainly not the Isle of Man, but Anglesey. (Bradley 384)

Müller also believes that both Ptolemaic forms are corrupt, but he suggests that the correct reading is Μονάουα [Monava], being related to the Welsh name Manaw, which Lorenz Diefenbach glosses as Mon of the Water. Diefenbach surmises that Anglesey Island, off the coast of Wales, was called Mon Fynydd, or Mon of the Mountains, to distinguish it from the other Mon (Müller 81, Diefenbach 122).

Paulus Orosius’s orthography is interesting:

The second remarkable matter is the form of the name of the Isle of Man. The oldest manuscript copy of this portion of Orosius’ text is Milan, Biblioteca Ambrosiana, D. 23 sup., an imperfect copy that breaks off at 2.13.7, written in Ireland in fine Irish half-uncial, verging towards minuscule and containing the earliest Insular carpet page (fol. Iv). It was dated by E. A. Lowe to saec. VII [the 7th century], but more securely by Bernhard Bischoff to c. AD 614. The Ambrosiana manuscript, alone of the early manuscripts, reads Evania. All other manuscripts, except for QZ1 (which read respectively Evanna, Evanea) read Mevania, and that is the form chosen by Zangemeister and Arnaud-Lindet. But the early Irish and Welsh examples show conclusively that Evania is correct. (Ó Corráin 123-124)

Ó Corráin believes that Mevania, and similar forms found in works based on Orosius, resulted from a conflation of two independent names for the island: Evania and Monapia (Ó Corráin 124).

Keith Fitzpatrick-Matthews identifies Manna of the Ravenna Cosmography with the Isle of Arran, one of the larger Scottish isles (Fitzpatrick-Matthews 80). He does not associate the Isle of Man with any of the toponyms in this work.

Etymology

The most popular explanation of the name Mona would derive it from the hypothetical Proto-Celtic word *moniyos, which means mountain (Pokorny 2007:1208).

The contributors to Roman Era Names have bucked this trend, identifying Ptolemy’s Monaoida with either Arran or Kintyre:

Μοναοιδα

Attested: Ptolemy 2,2,12 Μοναοιδα (or Μοναρινα), reported as an island and as part of Ireland.Where: Probably Arran, around NR9633, or possibly Kintyre.

Name origin: It is usually asserted that this name, like Mona, came from hills visible from the sea, but Greek μονος ‘alone, solitary’ is a better parallel. The final part –οιδα might be Greek for ‘swollen’, from οιδεω ‘to swell’ (compare modern oedema). The alternative final –ρινα looks like ρις/ρινος ‘nose, projecting spur of land’ and Gaelic word rinn ‘promontory’.

Notes: Ptolemy’s latitude/longitude coordinates around Ireland are a bit weird, but for this island his latitude figure (61.5°) lies between that of Ireland’s northern point (presumably Malin Head) and of Rathlin Island (Ρικινα) while his longitude is further east than anywhere else in Ireland. That narrows down the candidates to Kintyre (which is a peninsula not an island, but it is joined to the mainland by only a narrow neck about 1km wide at Tarbert), Sanda (which is tiny), and Arran. Arran wins because of Manna in the Cosmography. Most of the ancient island names up the west of Britain can be explained best with the aid of Greek, perhaps reflecting the speech of sea captains who first brought them to the notice of literate Mediterranean geographers, rather than of local people. Mona ± an extra qualification seems to have been a general name for big, isolated islands, where not all ancient authors may have been clear about the distinctions between Arran, Man, and Anglesey. (Roman Era Names)

Their commentary on the related toponym Mona is also worth quoting:

Mona

Attested: Caesar (de bello Gallico 5,13) Mona; Pliny Mona (2,187 & 4,103); Tacitus Monam insulam (3x); Dio/Xiphilinus Μονναν, Μοννης ; Ptolemy 2,2,12 Μονα island; RC [Ravenna Cosmograhy] Mona

Where: Caesar’s Mona was in medio cursu ‘half-way’ from Britain to Ireland, which fits the Isle of Man, and the text of RC hints that Mona was well north. On the other hand, in Pliny, Tacitus, and Dio, Mona clearly meant Anglesey, since they wrote after the Roman military had campaigned in north Wales before Boudicca’s rebellion. Caesar’s information probably came from ship-borne traders who had sailed in the Irish Sea, including perhaps Pytheas of Massalia, so it is unnecessary to follow R&S in thinking he was mistaken. Ptolemy’s latitude coordinate for Mona is unhelpfully weird.

Name origin: Greek μονος ‘solitary, alone’, originally describing the isolation of the Isle of Man, seems to have later become applied to Anglesey, thereby creating 2x Mona, so that Pliny used the name Monapia, literally ‘far off Mona’ to label the Isle of Man. Ptolemy then mentioned two more possible Monas, Μοναοιδα or Μοναρινα, literally ‘swollen Mona’ and ‘Mona ness ’, respectively, which would make sense as the Isle of Arran and the Mull of Kintyre, respectively.

Notes: Confused? You should be! Ancient writers may have been as puzzled as modern ones by all the M-vowel-N names that lie near the interface between ancient Irish and Welsh people. Besides Mona, Monapia, Μοναοιδα, and Μοναρινα, there were Manna, Maiona, and Menapii, plus possibly Menevia, Gerald of Wales’ name for St David’s in AD 1188, and the modern Monach Islands. To explain Mona up to a dozen etymologies need to be explored, many of which can be tracked down via the PIE roots of English man, mane, money, monger, monitor, monk, month, and monument. The explanation most often cited, but rejected here, was offered by R&S thus: “Mona is simply ‘mountain’ or ‘high island’”. This is usually linked to PIE *men- ‘to project’, the source of Latin mons ‘hill’. Also attractive but rejected as a parallel is proto-Celtic *mon-ī ‘to go’, which Matasovic (2009:276) reconstructs from Welsh mynd, Breton mont, Cornish mones, and Irish muinithir. (Roman Era Names)

Trying to identify Ptolemy’s Irish islands from the coordinates he assigns to them is probably a waste of time. As I pointed out in an earlier article in this series, the latitudes and longitudes Ptolemy records for these islands have all the appearances of artificiality. It was largely on the basis of Ptolemy’s coordinates that William Skene identified Monarina with Arran (Skene 69). And more recently, Louis Francis was misled by the northerly latitude of Monaoida to identify it with another of the Scottish isles, Mull (Francis Section 2).

Note that the etymologists at Roman Era Names believe that Pliny’s Monapia is not a corruption of Monarina:

The Mon- part is generally taken to be from PIE *men- ‘to project’, referring to the highest point in the Isle of Man, Snaefell. However, as explained under Mona, it is more likely to come from Greek μονος ‘alone, solitary’. The suffix -apia, from απιος [apios] ‘far off’ served to distinguish among multiple islands that were mona. (Roman Era Names)

Early Scholarship

William Camden amended Ptolemy’s Monoeda (as he read it) to Mona-eitha and identified it with the Isle of Man:

The Isle of Man ... Ptolemy calls it Monoeda, Mon-eitha, that is (if I may be allow’d a conjecture) the more remote Mona, to distinguish it from the other Mona or Anglesey. (Camden 1439)

In modern Welsh, eithaf means extreme or farthest.

The Welsh scholar William Baxter also identified this island with the Isle of Man. He believed that Ptolemy’s Monaœda was a corruption of Monaoecta, which he glossed as Mon üict, or small island. He defended his interpretation of mon as small by noting the modern Breton word moan, which means thin or slender (Baxter 175-176).

Goddard Orpen was one of the few scholars willing to defend Ptolemy’s reading Monaoida:

Μονάοιδα is the Isle of Man, the Monapia of Pliny, the Menavia of Orosius, and the Manna (perhaps Manua) of the Ravenna Geographer, Ir. Manainn, Welsh Manaw. Müller suggests that the form in Ptolemy’s text, Μοναοιδα, is a corruption of Μονάουα ; but might it not be connected with the name Manawydan, son of Llyr, the Welsh counterpart of the Irish god Manannan Mac Lir. If this connexion be phonologically admissible, it seems to bear out the following statement of Prof. Rhys : “Welsh seems likewise to have had two forms of the name [of the Isle of Man]. We have one the attested Manaw for an early Manavis or Manavja ; and Manawydan testifies to a longer one, Manawyᵭ for an early Manavija.” Is not this longer form attested by Ptolemy’s Μονάοιδα? (Orpen 128, Rhys 663 fn 2)

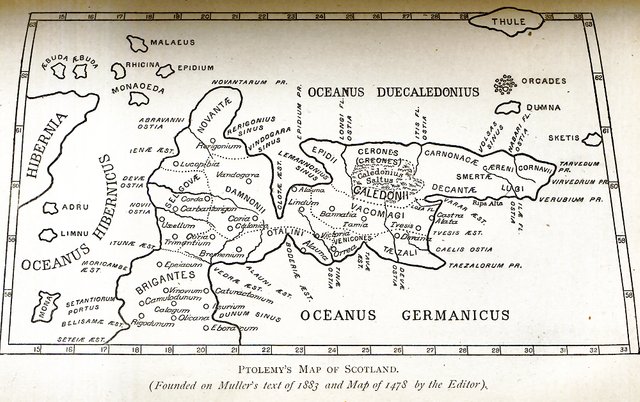

The French scholar André Berthelot suggested that Ptolemy’s location of the Isle of Man amongst the Aiboudai (Hebrides) was due to the misorientation of Ptolemy’s map of Scotland, which we discussed in the previous article in this series:

Monaoida (Mona of Pliny), Isle of Man, which is coupled with the peninsula of the Novantai, carried to the north by the ninety-degree rotation inflicted on Galloway. (Berthelot 247)

The Novantai were a Celtic tribe which Ptolemy located in Galloway in the extreme southwest of Scotland (Ptolemy 2:3:5, Müller 91).

Conclusion

There is little doubt in my mind that Ptolemy’s Monaoida refers to the Isle of Man, whatever the original and correct form of the name might have been.

References

- William Baxter, Glossarium Antiquitatum Britannicarum, sive Syllabus Etymologicus Antiquitatum Veteris Britanniae atque Iberniae temporibus Romanorum, Second Edition, London (1733)

- André Berthelot, L’Irlande de Ptolémée, in Revue Celtique, Volume 50, pp 238-247, Librairie Ancienne Honoré Champion, Paris (1933)

- Henry Bradley, Ptolemy’s Geography of the British Isles, Archæologia, Volume 48, Issue 2, pp 379-396, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge (1885)

- Julius Caesar, The Gallic War, With an English Translation by Henry John Edwards, Harvard University Press, Cambridge MA (1958)

- William Camden, Britannia: Or A Chorographical Description of Great Britain and Ireland, Together with the Adjacent Islands, Second Edition, Volume 2, Edmund Gibson, London (1722)

- Lorenz Diefenbach, Celtica, Volume 2, Imle & Liesching, Stuttgart (1839)

- Keith J Fitzpatrick-Matthews, Britannia in the Ravenna Cosmography: A Reassessment, Academia (2013)

- Ptolemy, Louis Francis (editor, translator), Geographia: Selections, English, University of Oxford Text Archive (1995)

- Karl Wilhelm Ludwig Müller (editor & translator), Klaudiou Ptolemaiou Geographike Hyphegesis (Claudii Ptolemæi Geographia), Volume 1, Alfredo Firmin Didot, Paris (1883)

- Karl Friedrich August Nobbe, Claudii Ptolemaei Geographia, Volume 1, Karl Tauchnitz, Leipzig (1845)

- Karl Friedrich August Nobbe, Claudii Ptolemaei Geographia, Volume 2, Karl Tauchnitz, Leipzig (1845)

- Donnchadh Ó Corráin, Orosius, Ireland, and Christianity, Peritia, Volume 28, pp 113-134, BREPOLS Publishers (2017)

- Paulus Orosius, Seven Books of History Against the Pagans, R P Pryne, Toronto (2015)

- Goddard H Orpen, Ptolemy’s Map of Ireland, The Journal of the Royal Society of Antiquaries of Ireland, Volume 4 (Fifth Series), Volume 24 (Consecutive Series), pp 115-128, Dublin (1894)

- Moritz Pinder, Gustav Parthey (editors), Ravennatis Anonymi Cosmographia et Gvidonis Geographica [The Cosmography of the Anonymous of Ravenna and the Geography of Guido of Pisa], Friedrich Nicolai, Berlin (1860)

- Pliny the Elder, John Bostock, Henry Thomas Riley, The Natural History of Pliny, Volume 1, Henry G Bohn, London (1855)

- Julius Pokorny, Indo-European Etymological Dictionary, Internet Archive, Opensource (2007)

- Julius Pokorny, Indogermanisches Etymologisches Wörterbuch, Volume 2, A Francke, Bern (1959)

- Claudius Ptolemaeus, Geography, Biblioteca Apostolica Vaticana, Vat Gr 191, fol 127-172 (Ireland: 138v–139r)

- John Rhys, Lectures on the Origin and Growth of Religion, As Illustrated by Celtic Heathendom, Williams and Norgate, London (1888)

- William Forbes Skene, Celtic Scotland: A History of Ancient Alban, Volume 1, D Douglas, Edinburgh (1886)

- Friedrich Wilhelm Wilberg, Claudii Ptolemaei Geographiae, Libri Octo: Graece et Latine ad Codicum Manu Scriptorum Fidem Edidit Frid. Guil. Wilberg, Essendiae Sumptibus et Typis G.D. Baedeker, Essen (1838)

Image Credits

- Ptolemy’s Map of Ireland: Wikimedia Commons, Nicholaus Germanus (cartographer), Public Domain

- Greek Letters: Wikimedia Commons, Future Perfect at Sunrise (artist), Public Domain

- The Isle of Man: © Copyright Independent Hostels UK 2019, Fair Use

- The Isle of Arran: © Graham Lewis, Creative Commons License

- The Isle of Anglesey: IACC © 2019, Isle of Anglesey County Council, Fair Use

- Snaefell (The Isle of Man): © John Radcliffe, Creative Commons License

- Ptolemy’s Map of Scotland (After Müller): William F Skene, Alexander MacBain (editor), The Highlanders of Scotland, Eneas MacKay, Stirling (1902), Public Domain

- The Isle of Man: © 2019 Visit Isle of Man, Fair Use

This post was shared in the Curation Collective Discord community for curators, and upvoted and resteemed by the @c-squared community account.

If you are a community leader and/or contest organizer, please join the Discord and let us know you if you would like to promote the posting of your community or contest.

@c-squared runs a community witness. Please consider using one of your witness votes on us here

Downvoting a post can decrease pending rewards and make it less visible. Common reasons:

Submit